English | Français | Português | العربية

A displaced person builds a shelter at the Mentao Nord camp in Burkina Faso. (Photo: Pablo Tosco/Oxfam)

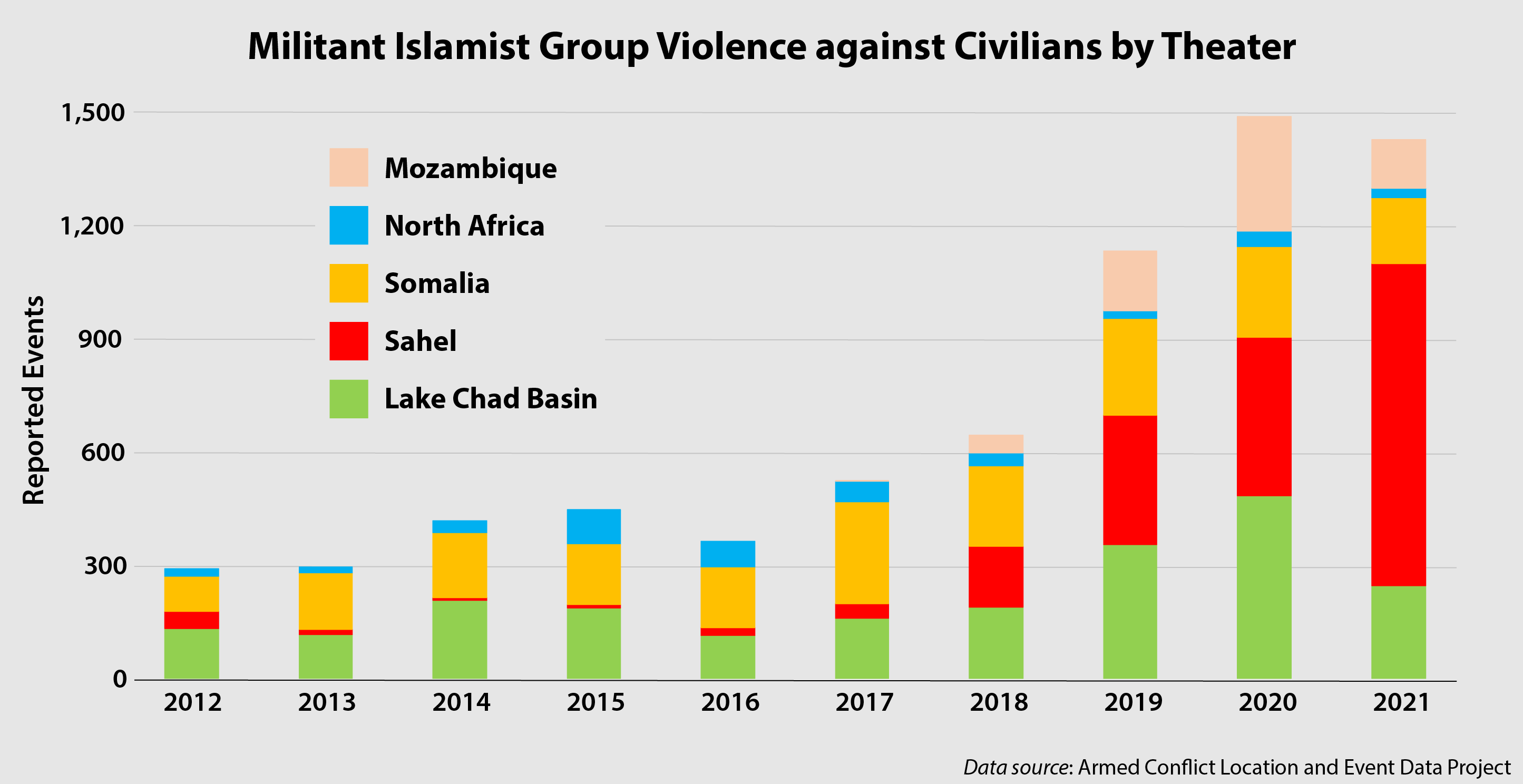

Africa has been experiencing a steady increase of militant Islamist violence over the past decade. This escalation has been characterized in recent years by an upsurge of violence targeting civilians. In 2021, a quarter of all militant Islamist-linked attacks were on civilians. This compares to 14 percent in 2016.

The frequency of attacks against civilians has varied in Africa’s five major theaters of militant Islamist violence—the Sahel, Somalia, the Lake Chad Basin, northern Mozambique, and North Africa—underscoring the distinct drivers and strategies of these groups. Understanding the variations in the patterns of violence against civilians across these local contexts, therefore, holds keys to enhancing civilian protection from these attacks.

The Strategic Logic of Violence against Civilians by Africa’s Militant Islamist Groups

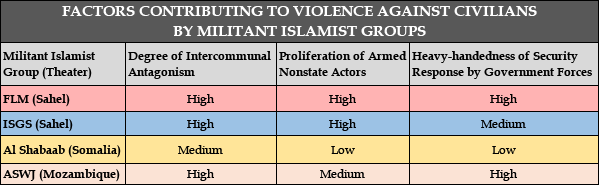

The structure of the competitive environment in which violent extremists operate greatly shapes each group’s strategies and target choices. For example, violent extremist groups that lack external sources of support and operate in areas characterized by low levels of outgroup hostility, are more likely to focus most of their attacks on state targets rather than on civilians. Groups that exercise a higher degree of control over a territory also tend to exercise more restraint in the use of violence against civilians.

Those that do target civilians, however, typically do so in multi-actor conflict environments marked by intense competition and high outgroup antagonism. Contexts of socioeconomic divisions by ethnicity, religion, livelihood, and race—and marked by strong ingroup/outgroup hostility and antagonism—correspond to higher levels of violence against civilians.

Peacekeepers from the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) patrol the streets of Gao, in northern Mali. (Photo: UN Photo/Marco Dormino)

Violence against civilians is also a function of weak organizational structures among militant groups. The inability of a militant group’s leadership to control their fighters’ behavior is strongly associated with higher levels of violence against civilians.

attack civilians. However, to the extent that government actions are seen as exacting collective punishment or conducted primarily based on a community’s ethnic composition, they can spur militant group recruitment resulting in increased extremists’ violence against civilians. Security force pressure may also trigger reprisals by militant Islamist groups aiming to intimidate local communities against cooperation with the government.

Building on these explanations for violence against civilians, this analysis offers insights into the developing trends of civilian violence in the Sahel, Somalia, and Mozambique.

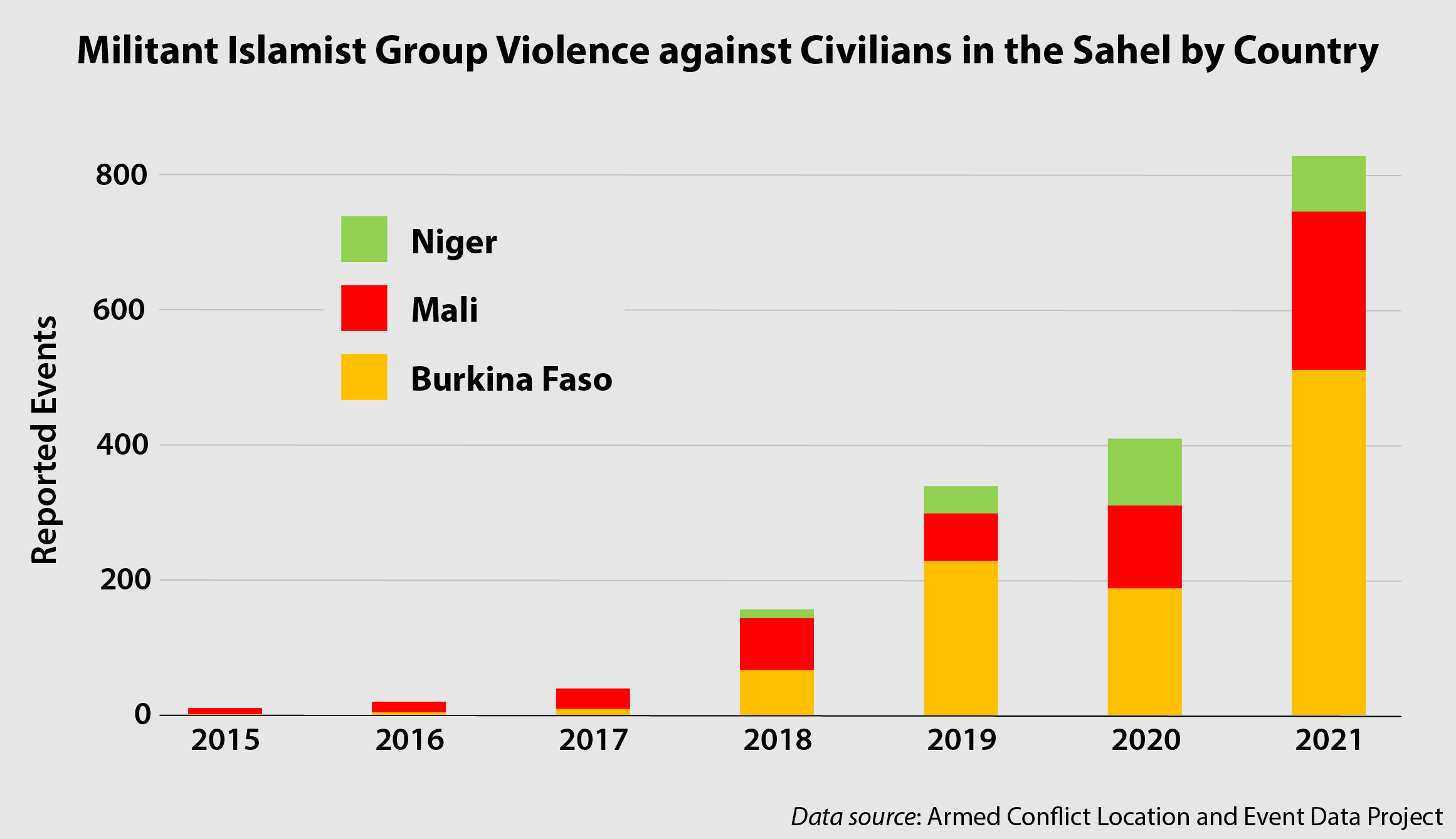

The Sahel’s Civilian Victimization Spiraling

The Sahel has seen a rapid escalation in militant Islamist group violence against civilians in recent years. In 2017, attacks on civilians comprised one-fifth of all acts of violence in the Sahel theater (38 out of 187 recorded violent events). That number reached 42 percent in 2021 (833 out of 2,005). This makes the Sahel the region with the highest level of militant Islamist violence targeting civilians across the continent, comprising 60 percent of all such violence against civilians in Africa.

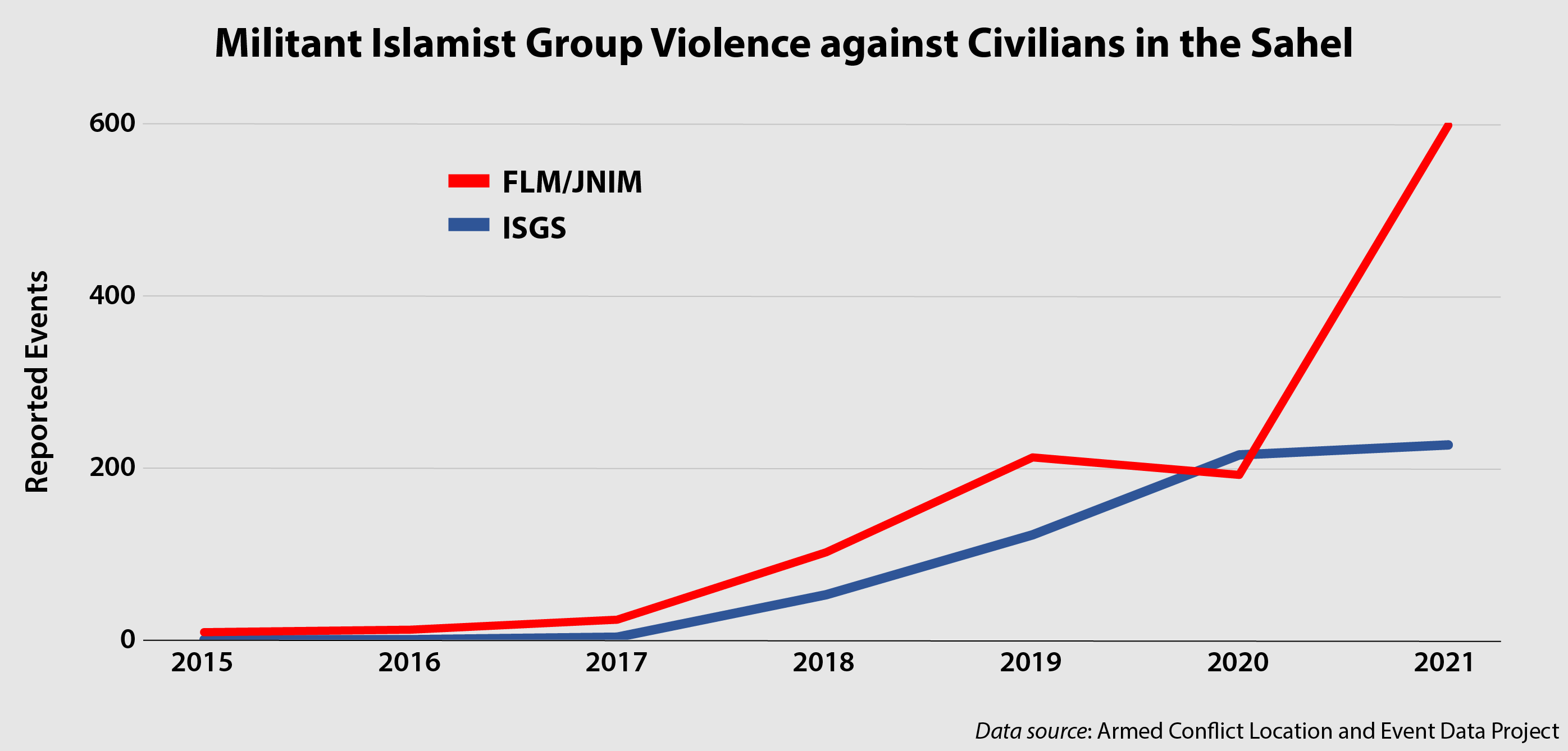

Levels of violence against civilians have varied across and within the Sahelian countries of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, as shifting conflict environments shaped the strategies and targeting patterns of the armed actors. These have primarily comprised the Macina Liberation Front (FLM) (the most active element of the Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) coalition) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS).

Intercommunal tensions have become highly polarized in contested regions of the Sahel. Militant Islamist groups have shrewdly exploited inter- and intracommunal rivalries over resources and rights. These groups have also amplified frustrations with the respective government’s perceived failings so as to ramp up recruitment among the long-aggrieved Fulani pastoralists vis-à-vis neighboring farming communities. This has prompted deadly tit-for-tat massacres by both militant Islamist groups and ethnic self-defense militias.

ISGS fighters near the Mali-Niger border. (Photo: saharan kotogo)

The dramatic expansion of militant Islamist activity in the Sahel in recent years—seen in both numbers of events and geographic reach—has apparently weakened the command-and-control structures of these groups. FLM and ISGS have struggled to rein in subordinates whose behavior has become more exploitative—controlling artisanal gold mines and extorting local communities. This has resulted in disconnects between the claims of the groups’ leaders in Mali and the actual behavior of their members or groups in peripheral places where the groups exercise a lower degree of territorial control.

In the Inner Niger Delta of central Mali, for example, Fulani nomads who joined FLM demanded that the group expand its attacks beyond security forces and their presumed local collaborators to also retaliate against entire Dogon farming villages suspected of complicity in Dogon hunters’ assaults on Fulani communities. Some dissatisfied Fulani fighters left FLM’s base in the Inner Niger Delta to bolster their communities’ defenses against Dogon attacks. These fighters, in turn, are allegedly responsible for various attacks on Dogon civilians in the region.

In other instances, confrontations between the militant Islamist groups themselves have contributed to the escalation of violence. In the wetlands of the Inner Niger Delta, conflicts within FLM erupted between local members from the Delta and those from the Seeno plains over access to the wetland grasses. The inability of FLM to resolve these tensions led some Seeno fighters to defect to groups connected to ISGS. ISGS’s aggressive attempts to exploit these divisions and peel combatants away from FLM deteriorated relations between the two and led to open confrontations between FLM and ISGS in 2020. The clashes between the two groups and their affiliates over territorial control and recruitment contributed to a sharp increase in violence and deaths of civilians caught in the middle as well as a weakening of ISGS’s operational capacity.

Government forces confronting Sahelian militant Islamist groups have, at times, added to the escalation of violence against civilians. Heavy-handed tactics by the security services have alienated certain Fulani pastoralist communities, reinforcing the outgroup narrative and driving militant Islamist group recruitment. This, in turn, has enabled more violence against civilians in contested regions. Government security forces’ reliance on communally based self-defense groups in their security operations, absent strong oversight, has also aggravated communal tensions and triggered more deadly forms of violence against civilians.

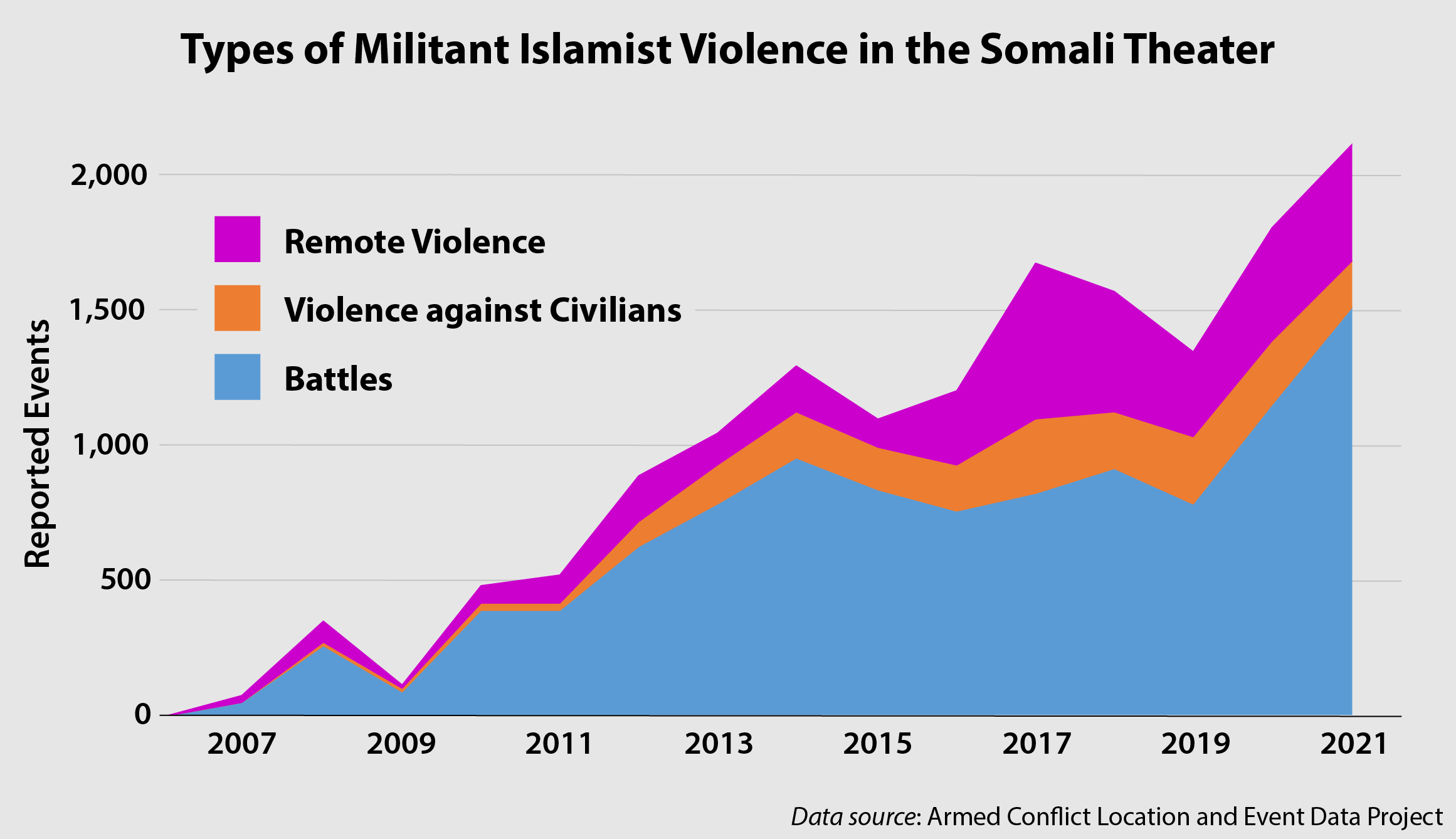

Dynamic Ebb and Flow of Violence in Somalia

Over the course of its insurgency in Somalia, al Shabaab has largely been involved in ambushes, complex attacks, and battles with state and nonstate security forces and AMISOM. To a lesser degree it employs suicide bombers, deploys improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and conducts targeted assassinations of government officials and civilians as a tool of intimidation. It also imposes harsh punishments on civilians violating the extremist group’s legal code. These attacks are largely aimed at controlling territory and influence vis-à-vis government and regional forces. Heavy-handedness by these forces is not widely seen as an escalator of al Shabaab violence against civilians.

Al Shabaab’s tactical use of violence against civilians has ebbed and flowed over time, adapting to numerous dynamics related to the security strategies of the Somali government and its partners. For example, at its territorial peak between 2009 and 2010, al Shabaab’s violent behavior against civilians was relatively restrained. The vast majority of violent events linked to al Shabaab during that timeframe were in the form of battles with Somali and international forces.

After interventions by regional security forces threatened the group’s survival, its territorial control shrank as did its ability to mount attacks on civilians. Over time the group increased its use of suicide bombings and IEDs (remote violence), which accounted for an 83-percent spike in civilian fatalities in Somalia between 2015 and 2016. Al Shabaab also escalated its civilian-targeted violence—against businesses that did not pay protection money, harshly punished dissent, and exacted revenge on its enemies. The next 3 years (2017-2019) were deadly for civilians, with al Shabaab perpetrating nearly 900 direct and indirect attacks on civilians in Somalia, resulting in estimates of nearly 2,000 fatalities. Most of these fatalities were due to IEDs. While al Shabaab plays on certain aspects of outgroup antagonism, having historically drawn most of its support from the Gaaljecel and Duduble sub-clans of the Hawiye clan, most of the civilian violence appears to be motivated as a tool for coercion.

As has been the case throughout al Shabaab’s 15-year-long insurgency, the group remains lethal in Somalia and a capable spoiler in the political sphere by exploiting interclan conflict and political factionalism in Somalia. Despite suffering several military setbacks and occasional internal splits, al Shabaab has demonstrated the ability to regroup, tactically evolve, and, through it all, thrive financially. These trends continued into 2021 with al Shabaab sustaining its campaign of suicide bombings and IED attacks against government and civilian targets in Mogadishu and other state capitals in Somalia.

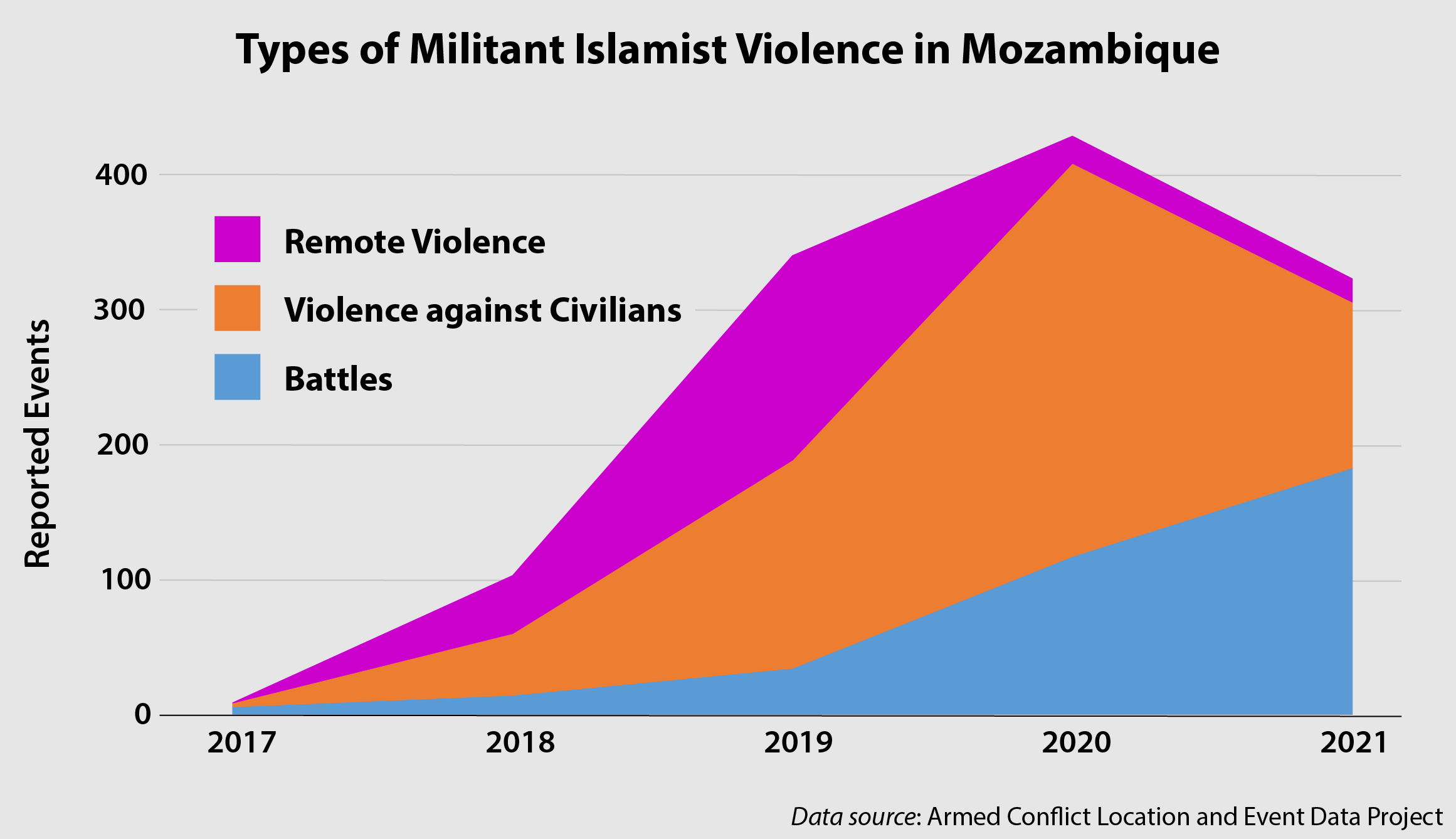

Escalatory Trajectory of Violence in Mozambique

The intensification of violence in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado Province has had a catastrophic impact on civilians. Since October 2017, when Ahlu Sunnah wa Jama’a (ASWJ) committed its first act of violence in Mocímboa da Praia, some 1,400 civilians have been killed and almost 750,000 civilians, roughly one-third of the total population of Cabo Delgado Province, have been displaced. ASWJ violence appears to have been primarily animated by two of the three amplifiers—outgroup antagonism and heavy-handed security responses.

Decades of government neglect and systematic underinvestment have left Cabo Delgado the poorest province in Mozambique. This has created a widespread sense of resentment and frustration, especially among Mwani and Makua ethnic groups, who blame the dominance of Maconde ethnic business elites and local officials—the ethnic group of President Filipe Nyusi—for the Mwani and Makua’s political and economic exclusion. The discovery of rubies in Montepuez in 2009 and liquid natural gas in the seabed off Palma in 2010 have exacerbated tensions, as communities who lost access to their fishing grounds or were cleared off their cultivated land in Cabo Delgado are yet to see promises of job opportunities and prosperity materialize. Scores of Mwani and Makua youth eventually joined ASWJ. Its first clashes with local government occurred in 2015 followed by the launching of a full-fledged violent extremist campaign in 2017.

Since then, ASWJ has been ruthless in its attacks on government facilities, security forces, perceived sympathizers of the dominant political party (the Liberation Front of Mozambique (Frelimo)), and civilians who refuse to comply with its dictates. ASWJ fighters have reportedly singled out Maconde, who are mostly Catholic and believed to be Frelimo backers, for the most brutal attacks, massacring civilians, desecrating their corpses, and burning their villages and towns.

Mozambican armed forces were ill-equipped and poorly trained to handle a militant Islamist insurgency. They responded to ASWJ’s brutal acts of violence with their own ruthless tactics that reportedly included the widespread use of torture, extrajudicial executions of civilians suspected of supporting the group, and the mutilation of bodies of presumed ASWJ fighters. This only further increased ASWJ recruitment and violent reprisals against civilians, which comprised two-thirds of ASWJ’s violent activity in 2020.

When the military and the police failed to stem the advances of ASWJ around Cabo Delgado, the government hired first Russian and then Zimbabwean and South African mercenaries. The government also encouraged civilians to form self-defense militias.

“The reversed trajectory of violence against civilians in Cabo Delgado reveals the potential difference of a more professional security response.”

Amnesty International accused one of the mercenaries, South African Dyck Advisory Group (DAG), of committing war crimes, including indiscriminately firing machine guns from helicopters and dropping hand grenades on civilians. The brutal tactics of DAG exacerbated already strained relations between some of the aggrieved communities of Cabo Delgado and the government.

The government then allowed the deployment of Rwandan and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) troops—including South African special forces—to Cabo Delgado. In 2021, the total level of ASWJ violent activity dropped by 25 percent, with attacks on civilians representing just over a third of those events. The reversed trajectory reveals the potential difference of a more professional security response.

Mitigating Militant Violence against Civilians

This review of militant Islamist group violence against civilians in Africa highlights how civilians are often targeted as part of intercommunal grievance narratives and as means of intimidation as violent extremists attempt to assert their territorial control. Heavy-handed security force responses, meanwhile, almost always have an escalating effect, driving recruitment for violent extremist groups and further endangering civilians in contested areas.

Each context is different and calls for a course correction must be attuned to local specificities and demands. Given the instrumentalized use of violence against civilians by militant Islamist groups, however, a reassessment and retargeting of responses is needed.

Women seated with their children as they wait to collect their food ration near Timbuktu, Mali. (Photo: EU/ECHO/Brahima Cissé)

Key among these is prioritizing efforts to prevent militant Islamist groups from exploiting existing communal tensions. The security environments in the Sahel and Mozambique could benefit from enhanced government and civil society efforts to ease ethnic tensions by facilitating ongoing intercommunal dialogues, strengthening dispute resolution mechanisms, and establishing more transparent and equitable land use and property rights rules.

In Mozambique, where the government is perceived by local communities as exploiting area resources, an independent body may be needed to facilitate such exchanges including the review of contracts. Governments aiming to reduce militant violence against civilians should also prioritize the provision of basic social services in marginalized areas to redress some of the systemic inequities and grievances underlying these intercommunal tensions.

Greater emphasis is also needed on training and deploying professional security forces. Avoiding heavy-handed responses that alienate already aggrieved communities can mitigate violent extremist recruitment. It can also reduce the likelihood that government forces inadvertently amplify intercommunal tensions. The deployment of disciplined, professional forces can also protect citizens in contested areas, creating a buffer between antagonized communities. These actions can collectively help break the sequence contributing to militant violence against civilians.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Surge in Militant Islamist Violence in the Sahel Dominates Africa’s Fight against Extremists,” Infographic, January 24, 2022.

- Gregory Pirio, Robert Pittelli, and Yussuf Adam, “Cries from the Community: Listening to the People of Cabo Delgado,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 30, 2021.

- Leif Brottem, “The Growing Complexity of Farmer-Herder Conflict in West and Central Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 39, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2021.

- International Crisis Group, “Stemming the Insurrection in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado,” Report No. 303, June 11, 2021.

- Clionadh Raleigh, Héni Nsaibia, Caitriona Dowd, “The Sahel Crisis since 2012,” African Affairs 120, no. 478, January 2021.

- Daniel Eizenga and Wendy Williams, “The Puzzle of JNIM and Militant Islamist Groups in the Sahel,” Africa Security Brief No. 38, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 2020.

- Anouar Boukhars, “The Logic of Violence in Africa’s Extremist Insurgencies,” Perspectives on Terrorism, October 30, 2020.

- Anouar Boukhars, “Keeping Terrorism at Bay in Mauritania,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 16, 2020.

- Pauline Le Roux, “Confronting Central Mali’s Extremist Threat,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 22, 2019.

- Joanne Crouch, “Counter-Terror and the Logic of Violence in Somalia’s Civil War: Time for a New Approach,” SaferWorld, November 2018.

More on: Africa Security Trends Countering Violent Extremism Sahel Security Trends Al Shabaab Extremism ISGS/Islamic State in the Greater Sahara Militant Islamist Groups