Reforms in Africa’s security sector require leaders with vision and the ability to persevere against inevitable resistance. Vignettes of African leaders who championed reforms demonstrate how these actions advance stability and increase public trust.

Frene Ginwala Shapes a New Order

Frene Ginwala (Photo: GovernmentZA)

Dr. Frene Ginwala is a stalwart of the African National Congress (ANC) who helped establish, build, and grow the ANC while she was in exile during the last 30 years of South Africa’s apartheid era. On her return home in 1991, Nelson Mandela asked Ginwala to represent the ANC in the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA), the body that negotiated the South African constitution. Joined by fellow party loyalists Govan Mbeki, Walter Sisulu, and others, Ginwala spearheaded a constitution-making process that was groundbreaking for its time. She championed a participatory approach that fostered broad ownership from groups outside the dominant ANC and instilled new norms of inclusion, consultation, and compromise in the institutions that would emerge from the CODESA process.

In 1992, Ginwala founded the Women’s National Coalition, a group of 100 community organizations that drew women and other marginalized groups into the constitutional negotiations. This coalition undertook a two-year consultative process involving public seminars and workshops that collected 3 million petitions from ordinary citizens on key issues under negotiation at CODESA, such as the constitutional framework, bill of rights, affirmative action, the electoral system, and checks and balances. Under Ginwala’s stewardship, the Women’s National Coalition also organized special consultations that brought security sector issues into the public debate for the first time in South Africa. The emphasis on citizen security that emerged from these discussion became the cornerstone of post-apartheid South Africa’s national security strategy. Ginwala credits the women’s movement for its ability to “link the struggle for national independence and security to the struggle for social equality and justice.”

The Constituent Assembly, the body tasked with drafting the final constitution, followed the Women’s National Coalition’s lead by embarking on a massive outreach program to incorporate citizen’s views into the draft constitution. More than 2 million submissions were received through a process involving more than 1,000 workshops attended by 20,549 people and 717 community-based organizations. Such high levels of participation gave the process considerable local ownership and legitimacy. In reflecting on the lessons of CODESA, Ginwala said, “We needed to undertake a project to inculcate new values in our society. It was not enough to include these values in our constitution. They need to be promoted throughout society.” This was ultimately the best way of ensuring that institutional reforms would emerge not as partisan creations of the ANC, but in service of all South Africans.

“We needed to undertake a project to inculcate new values in our society. It was not enough to include these values in our constitution.”

As a CODESA delegate, Ginwala also negotiated a new electoral model combining majority and minority representation. In 1994, Mandela asked her to take the helm as the first Speaker of the post-apartheid National Assembly. Under her watch, Parliament became a highly respected and independent institution, in spite of her party’s majority.

On some issues, parliament was at odds with the executive branch. Each time there was a disagreement, however, Mandela encouraged her to preserve the legislature’s independence. “Run parliament the way we ran CODESA,” he advised her. She took that guidance and created a participatory and consultative policymaking process that set the South African parliament apart. The parliamentary process required the executive branch to issue a Green Paper reflecting its views on new policy positions.

The paper would then be subjected to extensive public consultations with the media, civil society, community-based organizations, and other interested parties. The resulting document, known as a White Paper, would then be subjected to parliamentary scrutiny and sent back to the executive for refinement.

Ginwala used this process to steer the 1996 White Paper on National Defense and the 1998 White Paper on South African Participation in International Peace Missions—among the most participatory national security development processes in Africa—which enshrined civilian control, human security, and gender equality in South Africa’s new security doctrine.

Thuli Madonsela Picks up the Baton

Thuli Madonsela (Photo: Global Panorama)

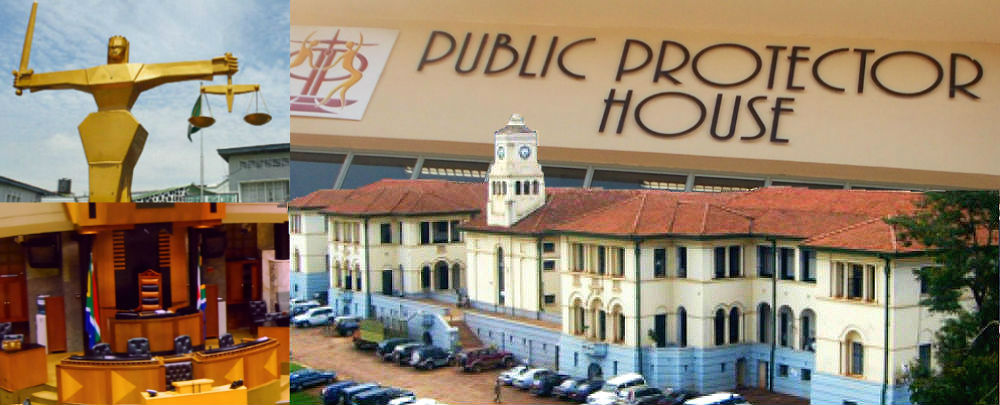

Thuli Madonsela belongs to the generation that picked up the baton of leadership from Ginwala and her colleagues. A member of the ANC since her teenage years, she honed her leadership skills at CODESA, where she participated in drafting the final constitution. She was then deployed to the Law Reform Commission where she played a key role in drafting new laws reflecting the values, norms, and institutional architecture that grew out of CODESA. But it was Madonsela’s role as Public Protector from 2009 to 2016 that earned her national and international acclaim.

Established to investigate abuses of state power and order remedies, the role of the Public Protector was thrust in the spotlight in November 2012 when Madonsela opened investigations into luxury upgrades at President Jacob Zuma’s private residence. Her groundbreaking report, Secure in Comfort, found that Zuma benefited unduly from the renovation and ordered him to return some of the money spent on the construction. Madonsela’s willingness to lead this probe was a demonstration of her courage and commitment to ethical leadership given the retribution she ultimately suffered from her fellow party members and leaders.

Several efforts to block the report were overruled by lower courts. A separate parliamentary probe that exonerated Zuma was deemed illegal by the Constitutional Court on the basis that the findings of the Public Prosecutor—an office established through Ginwala’s efforts—were legally binding.

Madonsela’s next investigation came at the request of members of the public. The resulting report, State Capture, detailed extensive corruption and racketeering involving, among others, the Gupta family—wealthy Indian immigrants with close ties to Zuma. The report ordered the presidency to appoint an independent inquiry headed by a judge assigned by the Chief Justice. The government again challenged the Public Prosecutor’s proscriptions. (The judgment on its challenge is currently pending.)

Madonsela’s next investigation came at the request of members of the public. The resulting report, State Capture, detailed extensive corruption and racketeering involving, among others, the Gupta family—wealthy Indian immigrants with close ties to Zuma. The report ordered the presidency to appoint an independent inquiry headed by a judge assigned by the Chief Justice. The government again challenged the Public Prosecutor’s proscriptions. (The judgment on its challenge is currently pending.)

Madonsela later noted how the Zuma administration differed from the Mandela years, saying that the former president “gladly submit[ted] his administration to the scrutiny of checks and balances, such as the courts and institutions supporting democracy, when its actions came into question.”

Time and again, Madonsela saw the power of accountability on South African society. She recalls one case where an elderly citizen had for decades been owed money by a local government. “We investigated and eventually he got his money. … He was so happy that … he went around telling everyone to go to the Public Protector because the system works.” Reflecting on many similar cases, Madonsela notes, “With accountability there is an opportunity for healing. … People are so forgiving. … They just want accountability and remedial measures when they have been wronged.”

“It is a reminder of the painful past and what it is that took us to the heart of the beast during apartheid … and what we need to do to ensure that never again do we live in a country where abuse of power and entrenched injustice creates such a huge trust deficit between the state and its people such that there is unrest, loss of life and despair,” she said.

“With accountability there is an opportunity for healing.”

Julia Sebutinde’s Quest to Tame a Feared Security Sector

Julia Sebutinde

Julia Sebutinde is an acclaimed Ugandan judge and international jurist known in Uganda as “Lady Justice,” “Probe Queen,” and “Iron Lady” for taking on the once-feared security services in a country that was still recovering from more than three decades of civil war and massive state-sponsored violence. She led three groundbreaking investigations into the Ugandan police, army, and revenue authority in 1999, 2002 and 2003—leading to mass sackings of officials and a series of reforms. Sebutinde went on to serve on the Special Court for Sierra Leone in 2005. In 2012, she became the first African woman to serve on the International Court of Justice.

In 1999, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni tapped her to lead the first major investigation into the police. Ugandans had participated in a consultative process leading to the adoption of a new constitution in 1995. However, corruption in the Ugandan security sector was beginning to sap public confidence in the reforms that emerged from the constitutional negotiations. Sebutinde faced an uphill task. “People were not used to seeing public officials account for anything,” she said. A member of her team noted, “The police was an absolute nuisance and untouchable. … People thought it was a waste of time.”

Ugandan police

Winning the public’s confidence was therefore key given the growing trust deficit and the public’s deep fear of security institutions. And so Sebutinde toured the country listening to complaints and then launched public hearings—a first for Uganda. Sebutinde’s final report described the police as a “mafia-type organization” that preyed on and was unaccountable to Ugandans. One key recommendation saw the creation of a unit to develop professional standards across the police force. Human rights and service delivery were introduced in the training curriculum, and all police stations were subjected to spot checks by the Human Rights Commission. Community policing was also adopted to restore confidence and trust.

Not all the police reforms proposed in the report were implemented, however. Moreover, the full probe into corruption in the army was not made public. Fifteen years later, questions are still raised about the behavior of the police, with many calling for the full implementation of the Sebutinde recommendations—evidence that the probes set a new standard for a more accountable security sector in Uganda. For ordinary citizens, the sight of a civilian taking senior police officials to task over maladministration and graft provided hope that they were in a new era where the security sector would serve the public, not vice versa.

Conclusion

Ginwala, Madonsela, and Sebutinde are all profiles in leadership. Ginwala fostered public ownership in new institutions through inclusiveness and participation. Madonsela jealously guarded those institutions in the current era, even under tremendous pressure from powerbrokers in the ruling party. Sebutinde convinced skeptical and fearful citizens of their ability to tame the dreaded security forces. All of these leaders understood that when trust between the government and citizens breaks down, the seeds of unrest are sown. They also knew that if their work was going to outlive them, they would need to set new standards and expectations that could be championed by reformers that followed. Indeed, leaders who leave behind strong, inclusive, and effective institutions wield great influence and enjoy the respect of their nations long after they leave office.

Additional Resources

- Paul Nantulya, “Wisdom from Africa on Ethical Leadership,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Spotlight, May 9, 2017.

- Blair Glencorse and Lawrence Yealue, “Five Leaders Exposing Corruption and Bringing Hope to Africa,” World Economic Forum on Africa, May 3, 2017.

- Paul Nantulya, “When Ethics Avert a Crisis: Two Cases from Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Spotlight, October 26, 2016.

- News 24 Frontline, “In Conversation with Thuli Madonsela,” video interview, October 12, 2016.

- Oluwakemi Okenyodo, “Governance, Accountability, and Security in Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 31, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 20, 2016.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “When Military Leaders Do the Right Thing,” Spotlight, October 28, 2015.

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa” Research Paper No. 6, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 31, 2015.

- Institute for Cultural Diplomacy, “An Interview with Julia Sebutinde,” video interview, November 25, 2014.

- Sanam Naraghi Anderlini and Camille Pampell Conaway, “Negotiating the Transition to Democracy and Reforming the Security Sector: The Vital Contributions of South African Women,” Women Waging Peace, August 2004.

- George W. Bush Institute, “Frene Ginwala Collection,” collection of video interviews.

More on: Corruption Democratization Leadership Managing Security Resources Military Professionalism South Africa Uganda