From left: Julius Nyerere, Gen. Henry Odillo, Gen. (ret’d) Henry Kwami Anyidoho, Gen. Katumba Wamala.

The colonial legacy of security forces protecting the regime over the people persists in some parts of Africa. Consequently, there is a growing recognition on the continent of the importance of enhancing security sector professionalism. Yet, it is the day-to-day practice of ethical leadership that is key to institutionalizing accountability, professionalism, and service to citizens. Examples below from Uganda, Malawi, Rwanda, and Tanzania offer lessons of how ethical leadership is central to maintaining public trust in the security sector and ultimately preserving stability and peace.

Defusing Tension

“The motto of the army college I went to was ‘not to promote war but to preserve peace’. … There is nothing as important as peace.”

Gen. Katumba Wamala. (Photo: US Army Africa.)

The run-up to the February 18, 2016, Ugandan presidential election was tense. The main opposition party accused the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) of raising a non-state force whose members were implicated in acts of intimidation and violence against opposition sympathizers. For their part, some opposition members reportedly formed their own militias, ostensibly to protect themselves. Tensions increased when a top ruling party official warned that the military would “shoot anyone who protested the election results.”

Determined to calm fears, at the start of the campaign in 2015, Gen. Katumba Wamala, then chief of the defense forces, issued an order: “All army officers are cautioned not to dare engage in politics and anybody who breaks the law will be dealt with.” He later announced that the army’s role “was not shooting civilians, but preserving the peace and enabling people to exercise their right to choose.” On the February 6 anniversary of the launch of the NRM’s armed resistance, he reiterated his resolve to an anxious public, noting that “the motto of the army college I went to was ‘not to promote war but to preserve peace’. … There is nothing as important as peace.”

Wamala’s record of service as a respected officer and reputation for having zero tolerance for political meddling lent credibility to his appeals. His statements on the eve of the polls were therefore viewed as consistent and trustworthy. Timely messaging from the army chief therefore helped defuse public anxiety and reinforced respect for the military’s nonpartisanship. This turned out to be crucial to ensuring a relatively calm post-election period.

Gen. Henry Odillo.

In 2012, the Malawian chief of defense forces, Gen. Henry Odillo, faced a different set of challenges, but his leadership similarly helped steer his country away from crisis. After the unexpected death of President Bingu wa Mutharika, some politicians jockeying for power reportedly invited Odillo to launch a coup. He refused. Like Wamala, he reminded them that the army was sworn to protect the constitution, not individual politicians. Two years later, Mutharika’s successor annulled the subsequent presidential elections citing “irregularities.” As rumors of a coup again began to swirl, Odillo made several forceful public statements affirming the army’s neutrality and ordering the military to “remain in the barracks and leave the civilians to solve the crisis.”

His ethical leadership created space for civilian leaders to negotiate and find political solutions that would avert a political crisis. Reflecting on the effect this had on Malawi’s stability, Zambian Brigadier General Joyce Ng’wane Puta remarked, “One cannot imagine what would have happened in Malawi if the army had succumbed to the ill-advised offer to seize power.”

Leading by Example

“The willingness of his troops to follow his lead was not solely based on obedience to orders, but on a personal commitment to what they saw as a moral decision.”

Henry Kwami Anyidoho (left) & Romeo Dallaire. (Photo: US Holocaust Memorial Museum.)

In 1994, Ghanaian General Henry Kwami Anyidoho served as the Deputy Force Commander of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) under Canadian General Romeo Dallaire. As tensions on the ground erupted into genocide, Dallaire was ordered to close his mission in order to avoid armed confrontation with the paramilitary Interahamwe and the Rwandan army.

Despite the risks, and after consulting his troops, Anyidoho assured Dallaire that the 454 soldiers in the Ghanaian contingent would remain in place. “I hadn’t even sought permission from home when I told [Dallaire] that we would stay,” he said. “We didn’t have an alternative. We couldn’t abandon these people.” The willingness of his troops to follow his lead was not solely based on obedience to orders, but on a personal commitment to what they saw as a moral decision.

“We were poorly equipped,” said Anyidoho. “We moved in soft-skin vehicles despite the fighting. Outgunned and outnumbered, we resorted to negotiations to achieve the protection mission we assigned ourselves. Everybody had to lead by example, and as operations progressed, the officers and soldiers saw that they were saving lives and so they defied the odds and kept going. That’s why we lost some of them.” Despite the difficulties, by putting ethics above all else, the Ghanaian contingent helped save around 30,000 lives, according to Dallaire.

Institutionalizing Ethics

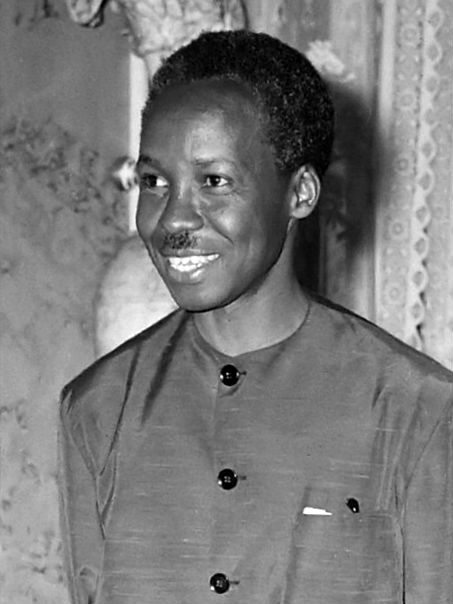

Julius Nyerere, 1965.

Away from the field, ethics education and training can be reinforced by the example of all levels of government. Tanzania’s founding president Julius Nyerere emphasized the importance of the civil service modeling ethical behavior. The concept of Ujamaa, meaning “brotherhood,” and its principles of “servant leadership” required senior leaders to practice honesty, accountability, good stewardship of public resources, accessibility to the public, and open government.

The values of Ujamaa were also instilled in all levels of the army through training and mentorship. This extended to the national youth service that provided a wide pool of potential recruits, as well as the Kivukoni Academy for senior civilian and military leaders. As a rule, civilian and military members trained together from the junior to senior level, creating healthy civil-military relations in the long term.

The biggest test of Nyerere’s approach came during Tanzania’s 1992 adoption of a multiparty system. The new constitutional principles separated the army from politics, breaking the influence it once had on the ruling party and government. Many feared that the army leadership would intervene to stall the process, but in the end, the military accepted its new status. This was due, in part, to the socialization in ethical values, coupled with a strong culture of civil-military relations, rooted in the Ujamaa years.

Key Lessons

In the Ugandan and Malawian cases, defense chiefs invoked constitutional principles to remind politicians and reassure the public of their independent and professional role in the nation’s security. The credibility of their messages was rooted in a proven record of ethical decision-making and leadership. And the results demonstrated the effectiveness of teaching by example.

In Rwanda, Anyidoho inspired his men by deciding to stay when others left. As a result, civilian protection became a personal mission of every member of the Ghanaian contingent and was reinforced when it became clear that their actions were saving lives. The institutionalization of leadership by example was also at the center of Julius Nyerere’s policies, which required ethics among the public service and the military. But if Nyerere had not ensured that the military leaders who needed to model these ethical standards were trained, these measures would arguably have had limited effect.

Additional Resources

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Research Paper No. 6, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2014.

- Dominique Djindjéré,“Democracy and the Chain of Command: A New Governance of Africa’s Security Sector,” Africa Security Brief 8, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, November 2008.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “African Role Models in Strategic Leadership,” Spotlight, May 11, 2016.

- Paul Nantulya, “Africa’s Strategic Future: The Consequence of Ethical Leadership,” Spotlight, October 3, 2015.

- Mark Doyle, “A Good Man in Rwanda,” British Broadcasting Corporation Report, April 3, 2014.

- Henry Kwami Anyidoho, “Effective Leadership Challenges in Africa’s Security Sector,” Video, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, October 26, 2016.

- Aleck Humphrey Cheponda, “Aspects of Nyerere’s Political Philosophy: A Study in the Dynamics of African Political Thought,” African Study Monographs, Volume 1, No. 3, December 1984.

More on: Leadership Malawi Tanzania Uganda