Download Full Report

English | Français | Português | العربية | አማርኛ

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- A Litany of Challenges for African Militaries

- Principles of Military Professionalism

- Obstacles to Military Professionalism in Africa

- Priorities for Building Professional African Militaries

- Conclusion

- Notes

- About the Author

Download Full Report

English | Français | Português | العربية | አማርኛ

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- A Litany of Challenges for African Militaries

- Principles of Military Professionalism

- Obstacles to Military Professionalism in Africa

- Priorities for Building Professional African Militaries

- Conclusion

- Notes

- About the Author

The Legacy of Colonialism

The simple starting point for why and how many African militaries have habitually interfered in economic and political matters is rooted in the colonial history of the continent. Built from the ashes of colonial forces, African militaries inherited the seeds of ethnic bias sown by the colonists that paved the way for a deficit of professionalism. Typically, minority ethnicities constituted the bulk of the colonial armed forces in order to counterbalance historically more powerful ethnicities. For example, the Tutsi minority in Burundi and Rwanda and the minority pastoralist peoples from the northern parts of Ghana, Nigeria, and Togo were predominant in the French and British colonial forces prior to independence.

This initial ethnic bias had a major impact on the formation of post-independence militaries. The wave of coups d’état that swept aside some of the first post-independence regimes was, in many cases, carried out by military officers from these ethnic minorities. A few notable leaders of this pattern include Étienne Eyadéma of Togo in 1963, Sangoulé Iamizana of Burkina Faso (then known as Upper Volta) in 1966, Jean Bédel Bokassa of the Central African Republic in 1966, and Idi Amin Dada of Uganda in 1971. Recognizing that their privileged position would be threatened by majority rule, these minority-led militaries had no incentive to support democratic change. Meanwhile, colonial forces saw little benefit in preparing African officers for a transition of rule. Thus, there were few qualified officers to assume command.

Fifty years later, the colonial legacy can no longer justify the persisting lack of professionalism among so many African militaries. After independence, African-led governments had the opportunity to build new and truly national militaries by reforming the structure, operations, and recruitment methods inherited from the colonists. Instead, post-independence leaders chose to exploit these shortcomings to create and maintain autocratic political systems. This has led to a myriad of ongoing challenges to military professionalism in Africa, including ethnic and tribal biases in the armed forces, persistent politicization of the military, and weak operational capacity.

Ethnic and Tribal Biases

A military organized around ethnic or tribal biases cannot defend the republic, much less the population. Instead, it can only defend the interests of its ethnic group or tribe. It lacks the popular trust, legitimacy, and competency of a merit-based force, hindering its effectiveness. Unfortunately, in many African countries the structure of the armed forces is still based on ethnic or tribal considerations.

For example, the army in Mauritania is split by racial, ethnic, and cultural divides. While a minority constituting less than a third of the population, the Arab-Berbers have dominated political, economic, and military institutions since independence.26 After allegations of an ethnically charged coup plot in 1987 threatened this dominance, Mauritanian President Ould Taya began a near-complete “Arabization” of all branches of the Mauritanian armed forces.

Similarly, in Chad, the ethnic composition of the armed forces is not reflective of the country as a whole. The Zaghawas, President Idriss Déby’s ethnic group, have dominated the army and key military posts ever since 1990 when they ousted Hissène Habré from power. The Togolese armed forces provide another example. Seventy-seven percent of the military personnel come from the northern part of the country. Of these, 70 percent are Kabyens, the same ethnic group as the President, including 42 percent who come from the President’s native village of Pya. Yet, the Kabye ethnicity makes up just 10-12 percent of the population of Togo.27

Recruiting the military predominantly from the ethnicity of the president is an all too common practice in Africa. Officers under such a chain of command are more loyal to the president than to the constitution. This practice undermines the professional standards of the armed forces while pitting the armed forces against one another on an ethnic basis. Such divisions were vividly exposed in the internal fighting that suddenly erupted in South Sudan in December 2013, severely setting back the security sector institution-building process in Africa’s youngest country.

A military composed of troops from communities across the country, on the other hand, can create a strong foundation upon which a democratic state can be built. A diversified force also creates conditions favorable to the professionalization of the armed forces as advancements are more likely to be merit- rather than ethnic-based, and allegiance would be to the nation as a whole rather than to a particular ethnicity. An example of an ethnically diverse military that is more representative of its society is found in Tanzania.

When the 6th Battalion of the King’s African Rifles was raised by British administrators at the end of World War I, soldiers were recruited from widely dispersed ethnicities across the country, including those who served under Great Britain’s adversary, the German Colonial Army. No ethnicity held dominance.28 Since Tanzania (then known as Tanganyika) was not considered to be suitable for colonial development, the British made no effort to create an ethnically biased military to control the majority population.29 Upon independence, Tanganyika’s first president, Julius Nyerere, purposefully maintained a professional distance from the military as he saw it as a tool of colonial repression. It was not until 1964, when Tanganyika and Zanzibar united to form Tanzania and the military faced a mutiny of soldiers seeking better pay and the removal of British officers that Nyerere changed his view. He subsequently set out to create a national identity among the military in order to prevent any destabilizing political interference.30

Similarly, in Zambia, the British recruited a military from different ethnic groups from across the country (then known as Northern Rhodesia). Thus, no ethnicity dominated Zambia’s military. Unlike Nyerere, however, Zambia’s future president, Kenneth Kaunda, collaborated closely with African officers of the colonial army at the outset, so there was little distrust between civilian and military leaders when Zambia attained independence in 1964. After independence, Kaunda continued a policy of “tribal balancing” at all levels of the government in recognition of the impetus that ethnoregional imbalances played in military interventions across Sub-Saharan Africa.31

A modern example of a military that became more inclusive is the South African National Defence Force (SANDF). A concerted postapartheid effort successfully created a military of men and women from formerly belligerent forces. Under the pressure of a political transition, the military transformed itself to represent and reflect the diversity of the South African people. The government, military, and civil society continue to maintain inclusivity as a part of South Africa’s national security policy.

The Burundian military also undertook extensive quota-based integration and enforced a retirement age to better reflect the Burundian population in the military. Under the strong commitment of its leadership, the military began an integration of mostly Hutu rebels into the Tutsi-dominated army after the 2003 ceasefire. This integration occurred at all levels of the military with soldiers from diverse ethnic backgrounds living and training together out of the same barracks. In 3 years, ethnically based prejudice in the military had been reduced dramatically, especially among young troops. The Burundian military has become more cohesive as a result.32

Politicization of the Military and Militarization of Politics

The politicization of the military is the tip of an iceberg that very often conceals an active competition among politicians for military support. In fact, a majority of military coups that have occurred in Africa were backed by competing political actors. When these competing interests are within the ruling party, “palace revolutions” instead of a complete interruption of constitutional order are more likely to occur. In Togo, for instance, upon the death of President Gnassingbé Eyadéma in 2005, his son Faure Gnassingbé replaced him after generals loyal to his father denied the leader of the National Assembly from taking over as prescribed by the constitution.

Some political parties will try to find sympathizers within the military with the aim of usurping power during times of crisis. Tellingly, the 2012 military coup in Mali gained support from several political parties despite unanimous condemnation from the international community. In Côte d’Ivoire, loyalists to former President Laurent Gbagbo continued to enlist the support of sympathizers within the military to help undermine President Alassane Ouattara’s authority.33 These politico-military imbroglios are illustrations of a common African theme: political actors relying on the military rather than the populace for support of their causes.

While high levels of military professionalism in certain Western countries have made obsolete the notion that individual politicians can subvert the security apparatus, the manipulation of military allegiances remains common in many African countries. But such an approach is inherently unstable. This was vividly illustrated in the experience of Côte d’Ivoire. When Côte d’Ivoire’s first president, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, assumed control of the security sector, he reduced its size and created a militia loyal to the party consisting mostly of Baoulé (Houphouët-Boigny’s ethnic group). Furthermore, he practiced a form of manipulation of the military by paying military officers high salaries compared to other civil servants and by giving top officers positions in the party and other perquisites.34

This imbalanced patronage paved the way for the subsequent spiral of political instability and insecurity in Côte d’Ivoire. Upon Houphouët-Boigny’s death in 1993, the president of the National Assembly, Henri Konan Bédié, seized power with the help of a few officers of the gendarmerie belonging to his tribe. By this act—unprecedented in the political and constitutional history of Côte d’Ivoire—the security forces cast aside their image of unity and neutrality and, from that point on, became central players in the political game.35 The same gendarmerie, subsequently better equipped and trained than the rest of the Ivorian armed forces, later installed Laurent Gbagbo as head of state following the 2000 elections in which his rival presidential candidate, the late General Robert Guéï, proclaimed himself winner. As in other African countries, elements of the security forces had become kingmakers.

The consequence of such relationships is a military that is more partisan and less professional in the eyes of society, thereby diminishing respect for the institution—something that is necessary in order to recruit committed, disciplined, and talented soldiers. The need for military support, meanwhile, explains why politicians are often willing to tolerate and, at times, encourage military leaders’ use of public resources for personal enrichment. The reality represents not only a politicization of the military but also the “militarization” of politics.

Presidential Guards: A Force Behind Nondemocratic Regimes

Presidential guards are a major political actor in Africa. In Burkina Faso, during the mutiny of 2011, the situation was relatively under control until members of the presidential guard joined in the protests. As a result, Prime Minister Tertius Zongo and his government were forced to step down, key military leaders were dismissed, and the demands of some mutineers were met. With those concessions, the same presidential guard led a forceful and definitive end to the mutiny of the soldiers.

The events in Burkina Faso illustrate the important role played by presidential guards in regime security and stability in Africa. In practice, presidential guards serve as a counterweight to the rest of the military and frequently play a central role in the various coups and countercoups launched in Africa. In Mauritania, President General Ould Abdel Aziz commanded the Autonomous Presidential Security Battalion (BASEP) for more than 15 years. While heading up this elite unit of the Mauritanian Army, he foiled two attempted coups d’état before leading one himself in 2008. In many African militaries, then, real power is in the hands of the presidential guard.

Presidential guards in Africa are generally better equipped, trained, and supervised than the rest of the armed forces. Because most African presidential guards are not controlled by the defense ministry or the armed forces’ chief of staff, they are commonly considered an army within an army. They are often highly politicized and in some cases have a strong ethnic bias. In other words, they bear all the hallmarks of unprofessionalism seen in African armed forces, yet are in an even more influential position relative to political power. As such, officers of the presidential guard are regularly the origin of poor security sector governance. In the interest of maintaining their pivotal role, such presidential guards are allergic to any reform that could call into question such privilege. Because they are under the direct control of the head of state, they act as a deterrent to the rest of the armed forces.

Some presidential guards have succeeded in helping African regimes maintain power through repression. In the 2012 elections in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, the presidential guard was active in rounding up key opposition figures, negating the legitimacy of this process. Ultimately, rule through repression is not sustainable. Instead, these actions undermine public trust and institutional integrity until the government reaches the point of collapse. Such was the case of Niger. In 1999, President Ibrahim Bare Mainassara was assassinated by his presidential guard. The guard’s commander, Major Daouda Mallam Wanké, assumed control of the country. Elections later that year put an army officer supported by the presidential guard, Mamadou Tandja, into power. Ten years later, in 2010, President Tandja was removed from power by a coup led not by the presidential guard, which had remained loyal, but by Army Major Salou Djibo after Tandja suspended government and announced that he would rule by decree.

Recognizing that their power is dependent on the head of state, many presidential guards in Africa are loyal and devoted to their benefactor’s cause irrespective of the constitutionality of his actions. They generally do not feel constrained, therefore, by legal strictures on human rights abuses committed under the guise of national security. In Guinea, for example, opposition protests in 2009 against the military junta leader, Captain Moussa Dadis Camara, ended in a bloodbath after members of his presidential guard opened fire on unarmed protesters in the national stadium during their rally. At least 157 people were killed, around 1,200 were injured, and at least 63 women were raped.36 Later, Camara himself was the victim of an assassination attempt initiated by the head of his presidential guard.

Weak Operational Capacity: A Sign of Militaries Without a Mission

The professionalism of a military relies on effective command and control systems, skills, and resources to carry out successful missions. The weak operational capacity within many African militaries renders them unable to play this role, calling into question their very relevance. The rout of the Malian military by Islamist rebels in 2012, the capture of Goma by the now defunct M23 rebel group in the Democratic Republic of the Congo the same year, and the disintegration of the Central African Republic military following the rapid and easy conquest of Bangui by Seleka rebel forces in 2013, are illustrative of the weak operational capacity of many Sub-Saharan militaries. Among the multitude of reasons that could explain this inefficacy, the following issues stand out: gaps in the chain of command leading to indiscipline, inadequate oversight of procurement practices, weak resource management diminishing operational capacity, poor morale, and a misaligned or obsolete mission.

Gaps in chain of command leading to indiscipline. A functional chain of command is a prerequisite for any military institution. It reflects good leadership and discipline and promotes accountability. Unfortunately, reports from around Africa paint a picture of militaries whose left hand does not appear to know what the right hand is doing. There is apparently very little connection between official military policy and the acts of the rank and file. One such example is in northern Nigeria where soldiers fighting Boko Haram insurgents have been accused of atrocities by civilians.37 Senior Nigerian military leaders have been at a loss to explain these actions despite being articulate in their understanding of the potential exacerbating effects that heavy-handed domestic security measures can cause among local populations.

The vast majority of African militaries are governed by legislative texts, such as the armed forces’ staff regulations and the military disciplinary code. However, criminal acts committed outside the barracks often go unpunished due to gaps in the chain of command and in the disciplinary protocol, perpetuating a view that military personnel in some countries are above the law. This reinforces a culture of impunity that undermines a military’s reputation and fosters deviant behavior among troops.

In Côte d’Ivoire under Laurent Gbagbo, no sanctions were taken against the perpetrators of a massacre in 2000—when soldiers loyal to Gbagbo killed civilians contesting the legitimacy of Gbagbo’s election. Nor was there any accountability for the killings during protest marches in 2004. After the democratic regime of Alassane Ouattara came to power in 2011, those perpetrators were indicted. However, the Ouattara government has yet to do the same with soldiers under its authority who committed crimes in the aftermath of the disputed 2010 elections.

There are exceptions, of course. In Benin, the judiciary on several occasions arrested detectives from the gendarmerie and the police for unlawful imprisonment and ill-treatment of citizens in police custody. In Burkina Faso, 566 soldiers involved in the mutiny of 2011 were discharged from the army, and 217 leaders of the mutiny were arrested, prosecuted by a military tribunal, and jailed for dishonoring the armed forces, causing public disorder, and violating human rights.38

Inadequate oversight of procurement practices. Another visible manifestation of poor governance in the military is in the procurement of supplies and equipment for the forces. Most troops will complain that life in the barracks is inhospitable, pay negligible, and opportunity for advancement nonexistent. Yet, the budget for the military is larger than most other public services. In Nigeria, for example, many military barracks remained in serious disrepair even after the military spent almost N12 billion (approximately $76 million) on barrack rehabilitation and construction.39 Allegations of corruption in the procurement of inferior equipment and diversion of supplies to Boko Haram have further eroded trust in the Nigerian military and directly compromised its effectiveness.

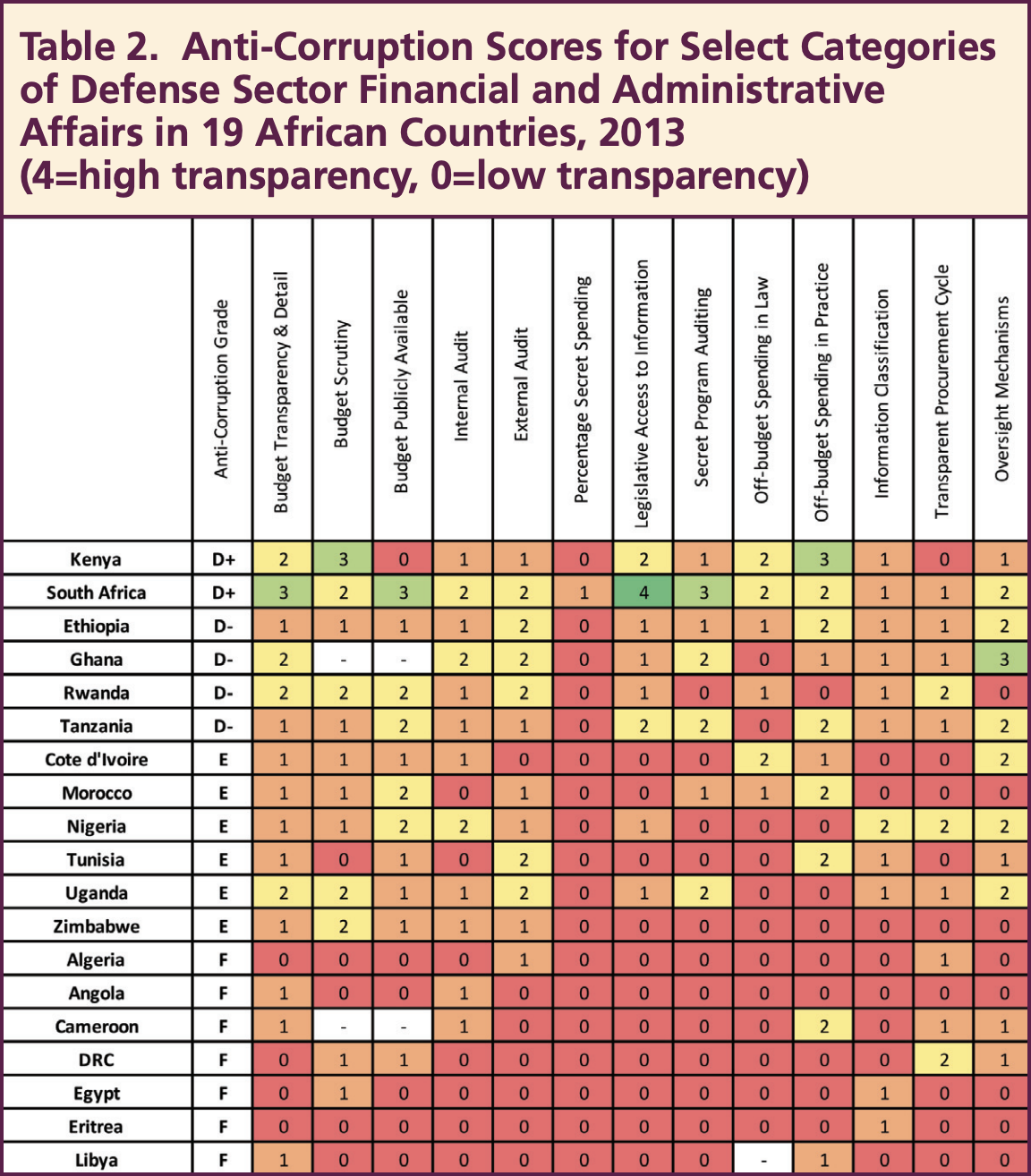

One reason for this disconnect is that defense ministries’ financial and administrative affairs departments are commonly just empty shells—severely understaffed and lacking the means to carry out their duties. The resulting weak oversight of procurement contracts by defense ministries enables widespread corruption and creates a governance problem. For example, in an assessment of 19 African defense sectors, Transparency International found 90 percent scored in the bottom two quintiles for transparency in the procurement cycle (see Table 2). Even if administrative procedures are respected in the early phases of the budget-making process, it only takes a stamp of “secret” or “classified” on these tenders to bypass audit by the public finance units. And while some military procurements may need to be confidential for national security purposes, the vast majority do not.

Source: Transparency International Defence and Security Programme, 2013.40 Anti-corruption grades are based on an assessment of scores across 77 categories of corruption risk.

In too many countries, military procurement decisions are concentrated in the hands of a political and military oligarchy allied with domestic and foreign commercial partners, making procurements more a function of business interests or self-enrichment than of addressing the armed forces’ true needs. In 2007, the bribe for military supplies in Africa was around 10 percent of the value of a contract.41

Bribery and kickbacks commonly lead to the procurement of overpriced equipment that is defective or ill-suited to the needs of the armed forces. In Uganda, for example, General Salim Saleh, a former guerilla and President Yoweri Museveni’s half-brother, was implicated in a number of political financing scandals before stepping down from his post as Senior Advisor to the President on Defence and Security.42 He procured not only spoiled food rations for the Ugandan army, but also defective and unusable T-54 and T-55 tanks, helicopters, and MiG-21 fighter jets. In exchange, the upper echelons of the military received a steady stream of bribes.43 In 2010, Cameroon’s former Defence Minister Remy Ze Meka was arrested on charges of embezzlement of funds for military operations and development projects during his tenure from 2004 to 2009. In 2013, the South African government of President Jacob Zuma was still trying to address evidence of kickbacks and bribery from an overly expensive military procurement package with international defense companies dating back to 1999 at a cost of more than $6 billion.

Certain African countries have put in place internal governance oversight mechanisms. For example, the majority of francophone countries in Africa have created inspection services departments under their defense ministries. This department is charged with monitoring, advising, and testing the operational capacity of the armed forces as well as the application of government policy. The department’s main tasks are to:

- control the application of laws, rules, and ministerial decisions regarding administrative and financial aspects of the armed forces

- participate in the development and implementation of military doctrine

- submit periodic reports on the management of human resources, equipment, training, and needs of the armed forces

While inspection services departments are an important institutional innovation, unless they are empowered, they can be easily circumvented. Such is the case when inspection services exist only to round out a defense ministry’s organizational chart and are simply dead-end appointments for former armed forces’ chiefs of staff or high-ranking military officers. These appointments, moreover, create conflicts of interest as the inspector general may end up reviewing contracts and decisions made by either himself or close colleagues while he had been in office. In some cases, personal relationships or ego influence the inspector general’s approach to the job, undermining the impartiality of this oversight function and negatively impacting operational capacity.

It is very rare in Africa for the legislative branch or civil society to question military leaders or become involved in opaque procurement processes. Typically, parliaments do not oversee military spending because, in most African countries, there is a belief that such inquiry would harm national security. For example, while Kenya ranks seventh among African countries in terms of defense budget expenditures,44 only in 2012 did it enact a law requiring the military to submit its financial reports to the parliament and president and to subject its accounts to audit.

Other African countries with relatively high levels of military spending, like Angola and Algeria, have laws in place requiring parliamentary oversight yet they do not appear to enforce them fully. In Ghana, there are three select committees of its parliament that deal with security and military-related issues, and the Defence and Interior Committee is chaired by the leader of the largest opposition party. This should provide a check on the security budgeting process. Yet, apparently when the issue of the budget is brought up, objection to its discussion for reasons of “national security” is commonly raised and not challenged.45 In Togo, 25 percent of the budget has typically been allocated to the military, making it the country’s largest line-item expense, but also the sector with the least external control.46 In other countries, such as Nigeria, the operational budget is decentralized, with the army, the navy, and the air force each having authority to handle its own procurement contracts for recurrent expenditures.47 This makes oversight even more challenging and creates more opportunity for the misappropriation of funds.

In contrast, countries like Senegal and South Africa have a robust civilian management structure within the defense ministries that contributes to a relatively high degree of accountability for the use of funds.48 In Burkina Faso, South Africa, and Uganda there is active legislative oversight in the formulation of the defense ministries’ budgets for adoption. And in countries like Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda, when political interference compromises either the ministry or the legislature, there is a vocal civil society to call the government to task. In 2012, for example, South African Minister of Defence and Military Veterans Lindiwe Sisulu was fired after the public became aware of her secretly negotiating a R2 billion (approximately $200 million) deal to purchase business jets for President Zuma and Deputy President Motlanthe.

Weak resource management diminishes operational capacity. Effective administration is indispensable to successful military operations. Only a sound management apparatus can harness the meager resources of African militaries and apply them to maximum effect. A lack of such capacity is perceptible at all levels in African militaries’ management of human resources, equipment, and logistics.

Politically and ethnically based promotions have upended the officer ranking pyramid in some countries. Before the crisis, the Malian army had more than 50 generals for about 20,000 troops: 1 general for every 400 men.49 Neighboring Niger had 1 general for every 600 men. In contrast, a typical NATO infantry brigade consists of approximately 3,200-5,500 troops and is commonly commanded by just 1 brigadier general or senior colonel. This disproportion of brass to rank and file is a common problem for African militaries. Typically, the larger the ratio of officers to enlisted soldiers makes an army more ineffective. Officer inflation is a source of inefficiency in the command and constitutes an extra burden for the defense budget. It is also a source of indiscipline at the top of the hierarchy as it engenders frustration among senior colonels who, seeing promotions go to other officers for political rather than professional reasons, sometimes disobey or refuse to take orders from new generals thereby sowing seeds of disobedience and indiscipline among the troops. This breaks the chain of command. The swift rise through the ranks of Uganda President Museveni’s son Brigadier General Muhoozi Kainerugaba (who became commander of Uganda’s elite Special Forces Command after only 15 years in service), for example, has raised the specter of nepotism and political gamesmanship.50

Disrepair of rolling stock and lack of maintenance have also contributed to the growing paralysis of Africa’s armed forces. African air forces are disappearing. The disengagement of international partners from costly technical maintenance coupled with a drastic reduction of defense budget allocations has grounded most planes. The majority of fighter pilots have, consequently, left the military. The lucky ones became commercial pilots for VIP flights, which have become the primary mission of Sub-Saharan air forces. Similarly, only South Africa still has significant operational “blue water” maritime capacities. This is not necessarily a negative development as the primary maritime threat faced in nearly every case is in coastal waters and exclusive economic zones (waters within 200 nautical miles of the coastline).51 However, small navies like those of Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Kenya, Senegal, and Tanzania suffer from obsolescence and maintenance problems.52

A major decline in the operational capacity of many Sub-Saharan militaries occurred in the 1990s after the end of the Cold War. It is not that these pre-Cold War militaries were any more professional. However, they at least had the bare minimum of serviceable equipment. This equipment was donated and serviced through generous cooperation agreements intended to support the ongoing superpower rivalry. The sudden end of the Cold War sounded the death knell for these outlays. Deprived of the support from both Western and Eastern Blocs, the Sub-Saharan militaries were unable to maintain the illusion of cohesion and operational capacity. In Burkina Faso, for instance, 1999 signaled the end of German cooperation programs that had strengthened the engineer corps. The withdrawal of funding dramatically restricted the activities for this unit, which had been contributing immensely to the opening of Burkina Faso’s rural areas by constructing and rehabilitating roads.

The conflict in Mali in 2012-2013 revealed the management challenges within neighboring states’ militaries. Despite its past peacekeeping experience in the region, ECOWAS could not set up and deploy a reliable force to stop the rapid advance of jihadist forces. After observing ECOWAS’ hesitation to deploy its standby forces, France intervened, backed by UN Security Council Resolution 2085, to restore the territorial integrity of Mali and to prevent the militant groups from strengthening their positions in the region. The truth is that few West African countries had the logistical capacity to deploy a battalion on their own without external support.

Not all African militaries are in such a state of obsolescence. The armed forces of Algeria, Morocco, and South Africa generally have effective and well-trained militaries capable of carrying out combined (intermilitary) operations and providing logistical support for a conflict. Credit must also go to the armed forces of the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). Comprised of contingents from Uganda, Burundi, Djibouti, Ethopia, Kenya, and Sierra Leone, AMISOM restored order and stabilized the main cities in Somalia.53 Likewise, the Chadian Armed Forces were able to deploy on short notice 2,000 desert-trained troops to engage militant Islamist forces in the Adrar des Ifoghas region in northern Mali during the 2012 multinational intervention. Nigerian forces, similarly, played a critical role in the stabilization effort of northern Mali. The 3,000-troop UN Force Intervention Brigade in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)—comprised of troops from South Africa, Tanzania, and Malawi—was decisive in the 2013 defeat of the M23 rebels who had been a major destabilizing force in eastern DRC.

Poor morale. African militaries do produce highly competent and professional officers trained in the world’s best military schools. Unfortunately, these officers are unable to flourish in an environment where competence and professionalism are not rewarded with promotion or rank advancement. Resulting idleness and professional stagnation eat away at the motivation of even well-trained and competent officers. This lays the groundwork for recurring mutinies among troops who feel directionless and abandoned by their military and civilian leaders.

Morale is vital on the battlefield. Without it, defeat is unavoidable. The lack of motivation of Malian troops to fight against militant Islamists and Tuareg separatists in 2012-2013 was due to a combination of factors, including political instability caused by the military coup, allegations of corruption at senior levels in the chain of command, and minimal support and equipment to frontline troops tasked with combatting the militants.

Corruption at the top of the chain of command undermines the morale of the troops, making them increasingly prone to participating in or condoning corrupt practices themselves.54 In countries where pay is paltry and irregular, soldiers are tempted to extort money or in-kind payments from the local population or turn to profit-oriented activities to survive. As in other African militaries, Malian military officers allegedly “recruited” more troops than actually existed while simultaneously selling the equipment and pocketing the pay issued to such “ghost” troops.55 Sometimes, soldiers simply go on strike. In the DRC, for example, media reports linked the nonpayment of troops deployed in the eastern region to corruption at the top. These troops, in turn, failed to protect villages against incursions from the Lord’s Resistance Army of Uganda.56

The most reckless soldiers are all too willing to turn to organized crime. Following the nonpayment of salaries in the 1990s, the top brass of GuineaBissau’s military began selling weapons and landmines to Casamance rebels before turning to drug trafficking. The political and military upheavals and bloody score-settling that have been destabilizing Guinea-Bissau ever since are closely tied to the drug trafficking that has corrupted the government and military leadership.57

The same drug trafficking cartels have infiltrated other West African countries and compromised their political and military leadership in other ways. The former Malian leader, Amadou Toumani Touré, attempted to exploit the organized crime syndicates as a way of exerting influence in the north.58 Members of Mali’s military were offered up to provide temporary leadership to the private armies of smugglers.59 Sometimes Malian officials were even directly involved in clashes between criminal syndicates.60 Though not an excuse to depose a democratically elected government, its ties with organized crime set the Malian regime up for a loss of legitimacy and an erosion in its effectiveness.

Misaligned or obsolete mission. Stanisław Andrzejewski posited that “an unoccupied military, with no external threat to address, was more likely to interfere in domestic politics.”61 This rings true for Africa, where many militaries suffer from a lack of vision and clear objective. In this way, obsolete rolling stock and ill-prepared, unmotivated troops are merely symptoms of a larger challenge. There are only a limited number of African countries with a defined national security strategy. A security strategy is essential to align resources to identified national priorities, to coordinate multi-institutional efforts, and to foster a shared understanding of the roles and responsibilities of all branches of government for the benefit of the state, the military, and civil society.

For the majority of African armed forces, the guiding doctrine of the military is still founded upon the defense of the nation from a foreign enemy. Yet, there have been few interstate conflicts in Africa, particularly over the last several decades. Moreover, African states have managed to use international mechanisms to resolve border disputes peacefully. Border disagreements between Nigeria and Cameroon, Burkina Faso and Mali, as well as Benin and Niger have all been resolved through the International Court of Justice at The Hague.

Africa’s threats, instead, are nearly entirely domestic in nature. Boko Haram and the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta have been defying Nigerian authorities for a number of years. The governments of Angola and Senegal have been struggling for decades to defeat the tenacious separatist forces in the Cabinda and Casamance provinces, respectively. Tuareg separatists, aided by an assortment of militant Islamist groups, took advantage of the political uncertainty in Bamako to make gains in their fight for control of northern Mali. Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony and his irregular forces have committed heinous crimes against the Ugandan, Congolese, and Central African populations for decades despite the efforts of their respective national militaries. The violent extremist group al Shabaab persists as a risk to stability in Somalia.

These homegrown insurgencies underscore the disconnect between military mandate and actual security threat. In some countries, the irregular forces confronting the government forces are better equipped, more mobile, and have better knowledge of the terrain.62 African security forces, therefore, must become demonstrably more competent and professional in order to prevail. Until African leaders identify a clear mission for their security institutions and incorporate this into their strategic planning processes, they will be unable to resource and train their troops for the real security challenges they face.