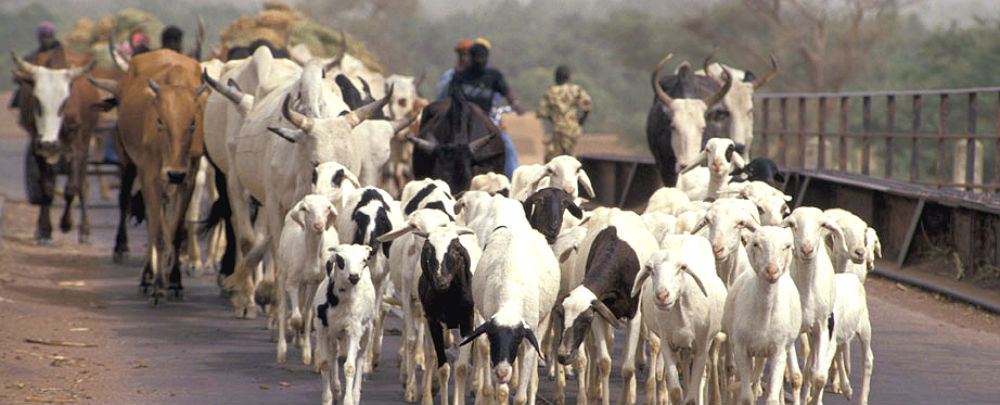

Herding cattle in Mali. (Photo: © Curt Carnemark / World Bank)

An increase in farmer-herder tensions is exacerbating a fragile security environment in central Mali. In an interview with the Africa Center, Lieutenant Colonel Alou Boi Diarra reviews the factors that have led to the growing farmer-herder crisis and what can be done to reverse them. A recent graduate of the National Defense University’s College of International Security Affairs in Washington, DC, Colonel Diarra’s thesis, “Armed National Building: Disbanding Ethnic Militias and Ending Farmer-Herder Violence in Central Mali,” earned him four distinguished awards, including NDU’s Outstanding International Fellow Award.

What is the significance of farmer-herder violence in Mali?

Persistent intercommunal violence between Fulani pastoralist communities and Bambara and Dogon farmer communities constitutes an existential threat to a united, peaceful Malian nation. In March 2019, more than 150 Fulani herders were killed by Dogon militias in Central Mali. In June, a raid by Fulani herdsmen on Dogon villages claimed at least 35 lives.

In the Sahel, and within Mali, farmer-herder conflict was once resolved through local customary mechanisms and traditional agreements on boundaries demarcating grazing and farm land, access to pasture, and regulated migration. Many of these systems have been eroded in the contemporary period, as force has replaced the power of traditional diplomacy and customary norms.

The availability of weapons, coupled with complex connections between criminal organizations, traffickers, and terrorist groups, has enabled a culture of violence to take root and spread throughout Mali. This is weakening incentives to coexist peacefully and resolve conflicts through nonviolent means.

What are the key drivers of conflict between pastoralists and farmer communities?

A Malian farmer. (Photo: UN / Marco Dormino)

The violence is primarily rooted in competition for scarce resources needed to sustain economic livelihoods in a context of climate change, demographic shifts, external ideological influences, an ongoing jihadist insurgency, and political manipulation by local elites. These problems are compounded by weak—or in some cases nonexistent—governance in Mali’s remote areas. It is in this environment of state fragility, weakened local and national governance, economic inequalities, and generalized insecurity that communities have organized themselves into militias to defend their livelihoods, villages, and families. The violence has also been worsened by the use of sectarian narratives by all sides aimed at dehumanizing perceived enemies. All of these elements contribute to the context that drives these conflicts and renders them resistant to peaceful resolution.

To what extent does religious extremism exacerbate farmer-herder violence?

Religion is not the primary factor in the ongoing violence. Fulani herder communities share the same Islamic beliefs as their neighboring Bambara and Dogon farmer communities. The key problem, in as far as religion is concerned, is that jihadist groups exploit the preexisting fault lines to further their objectives. For instance, the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (GSIM) more commonly known as Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM), a coalition of extremist groups operating in Central Mali, has been particularly effective in this regard.

Its ability to manipulate farmer-herder identities challenges the dominant narrative that jihadist groups always fight for international causes. This group adopted an “indigenization strategy” focusing on local issues. It aligned itself to Fulani causes, for instance, allying with the radical Fulani cleric Amadou Kouffa, who remains a potent symbol of Fulani resistance. As the leader of the extremist Macina Liberation Front, or Katiba Macina, Kouffa helped JNIM mobilize local young Fulani herders by echoing their grievances against the established land tenure system that is dominated by farmer communities.

What are some effective responses the government can take?

“The government should adopt a people-centered security strategy aimed at re-establishing trust.”

The Malian government has undertaken numerous measures to stop the violence, and its recent political initiatives are yielding encouraging results. Nevertheless, the continuous cycle of attacks and reprisals suggests that current responses are insufficient. Because the early manifestations of the crisis tended to target state institutions, agents, and symbols, the Malian government’s responses were understandably state-centric. However, they had the unintended consequence of neglecting large parts of the population, which felt increasingly vulnerable and suspicious of the government’s intentions.

In learning this lesson, the government should adopt a people-centered security strategy aimed at reestablishing trust with affected populations and building a cohesive, inclusive, and democratic nation. Legitimacy in this context should be based on the government’s ability to protect all communities while preserving civil liberties, protecting human rights, and enhancing the rule of law.

A new intervention strategy should focus on four main issues:

- First, governance reforms should center on restoring government legitimacy and the rule of law, creating economic opportunities, improving livelihoods, and leveraging customary mechanisms for airing grievances at the community level.

- Second, development efforts should address the underlying social and economic grievances, including the establishing of a more consensual land tenure policy.

- Third, the government should enhance its strategic communications efforts to better shape internal and external perceptions, counter the spread of harmful terrorist narratives, and promote legitimacy, reconciliation, national unity, and healing.

- Finally, the government should harness the international community’s involvement in ways that support inclusive and people-centered human security paradigms.

What roles can citizen groups play in mitigating these tensions?

A strong nation can only be built from the ground up, with the active involvement of all citizens. Malians have strongly condemned violence on all sides, which is proof that citizens remain sensitive to the fate of their fellow countrymen. However, the risk of polarization and fragmentation remains due to the high levels of tension and inflammatory rhetoric. Furthermore, the growing economic divide between urban and rural populations is making it more difficult to develop a shared identity that cuts across the Malian society.

“Citizen ownership and engagement with security issues … is the only viable path to a sustainable peace that addresses the root causes of deadly violence.”

Civil society organizations have an important role in complementing government efforts by promoting community-level dialogue and reconciliation initiatives, empowering and reinforcing traditional mechanisms of conflict resolution, and fostering inclusive security.

The initiative by Malian civil society organizations to launch the Civil Society White Book for Peace and Security in February 2019 demonstrates the resilience and continued relevance of Malian civil society organizations in addressing the challenges facing the country. It brought together more than 90 representatives from civil society, academia, and the policy community to build consensus around human security approaches to the crises facing the country.

Such initiatives underscore the value of citizen ownership and engagement with security issues, as this is the only viable path to a sustainable peace that addresses the root causes of deadly violence.

Additional Resources

- Pauline Le Roux, “Ansaroul Islam: The Rise and Decline of a Militant Islamist Group in the Sahel,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 29, 2019.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Frontlines in Flux in Battle against African Militant Islamist Groups,” Infographic, July 9, 2019.

- Pauline Le Roux, “Exploiting Borders in the Sahel: The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 10, 2019.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “A Review of Major Regional Security Efforts in the Sahel,” Infographic, March 4, 2019.

- Pauline Le Roux, “Confronting Central Mali’s Extremist Threat,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 22, 2019.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “The Complex and Growing Threat of Militant Islamist Groups in the Sahel,” Infographic, February 15, 2019.

More on: Identity Conflict Sahel Security Trends Ethnic Conflict Extremism Governance Mali Sahel