A dhow in the Indian Ocean suspected to be under pirate control. Note the sandbags on the deck, possibly an attempt to fortify the craft against small-arms fire.

The Indian Ocean is a vital geopolitical hub that connects trade routes in Africa, the Asia-Pacific region, the Middle East, and Australia. Its abundance of national, regional, and shared maritime economic resources is accompanied by a proliferation of security threats including trafficking of humans, weapons, narcotics and other illicit substances, illegal fishing, and piracy. Assis Malaquias, a former Professor and Academic Chair of Defense Economics and Resource Management at the Africa Center, shares his insights on the relevance of the Western Indian Ocean in the larger maritime safety and security agenda on the African continent.

Question: What is the strategic importance of the Indian Ocean maritime region to the broader regional and international security agenda?

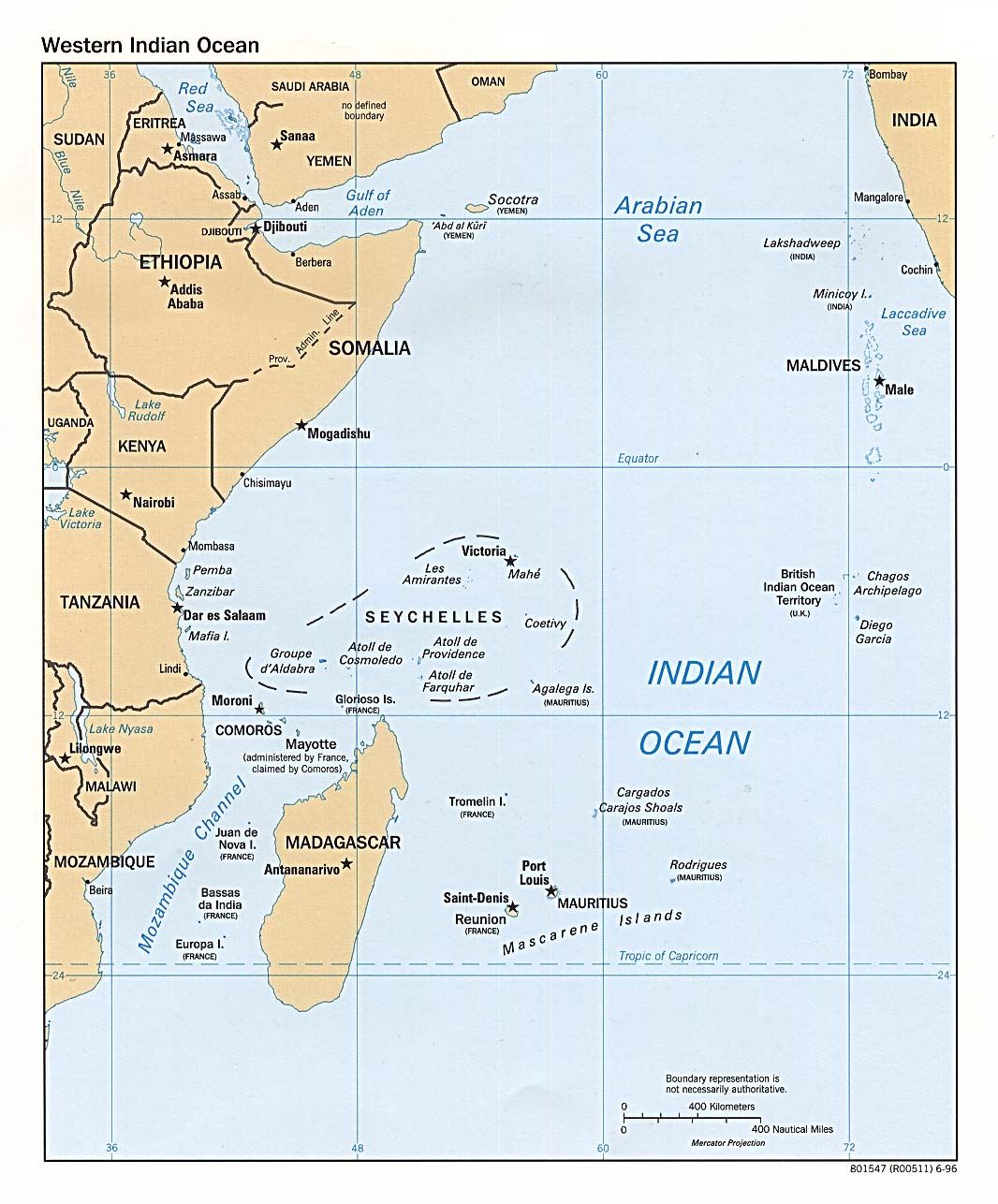

ASSIS MALAQUIAS: The Indian Ocean’s strategic value cannot be overstated. It touches four continents, stretching from the southernmost tip of Africa, north to the Suez Canal, east to the Indonesian archipelago and Australia, and south to Antarctica. Roughly 50 percent of oil and 40 percent of gas shipments traverse the Indian Ocean. Ports on the ocean’s shores handle approximately 30 percent of global trade and about half of the world’s container traffic. Additionally, crucial mineral resources such as uranium, cobalt, nickel, aluminum, and fishing stocks are abundant in the region, among both coastal and inland states. Securing the choke points in the Indian Ocean—such as the Straits of Hormuz and Malacca, and Bab el Mandeb, which connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden—is strategically vital for the global flow of trade, which is why even some states outside the Indian Ocean maritime area maintain a naval presence in it.

The Indian Ocean also borders zones of conflict, including Somalia and Sudan, and countries that suffer from weak government structures and limited capacity for policing offshore activities. As a result, illicit trade and other activities have flourished in many parts of the Indian Ocean. The collapse of central authority in Somalia, for example, is partly responsible for the emergence of piracy, which started along the Somalian coastline and eventually extended all the way to the Indian subcontinent. Several countries with global trade interests, including the United States, India, and China, have had to launch counter-piracy operations as a result.

The Indian Ocean also borders zones of conflict, including Somalia and Sudan, and countries that suffer from weak government structures and limited capacity for policing offshore activities. As a result, illicit trade and other activities have flourished in many parts of the Indian Ocean. The collapse of central authority in Somalia, for example, is partly responsible for the emergence of piracy, which started along the Somalian coastline and eventually extended all the way to the Indian subcontinent. Several countries with global trade interests, including the United States, India, and China, have had to launch counter-piracy operations as a result.

Q: What efforts are underway to marshal more efforts and resources in this important maritime domain?

AM: African national and regional security strategies have, for the most part, centered on land-based threats. This is not sustainable, given that 38 African countries are either coastal or island states and only 16 are landlocked. A great many Africans living along the continent’s 16,000 miles of coastline have a sea-based culture going back millennia. Moreover, half a billion Africans rely on fish for their protein intake. Some of the world’s most vital trade routes encircle Africa, yet the continent’s share of global trade is just 2 percent.

African countries, however, are starting to invest in the institutions and processes needed to harness the vast potential of the maritime domain. In 2012, the African Union adopted the 2050 African Integrated Maritime Strategy, which outlines an overall strategy and plan of action to address Africa’s maritime challenges and exploit opportunities for sustainable development and competitiveness. This effort represents an emerging policy shift from “sea blindness” to increased awareness of the maritime domain and coordinated responses to insecurity.

The 2050 strategy built on earlier efforts, starting with the adoption in 2008 of a regional maritime security strategy by the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), followed by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) maritime strategy in 2011, and the 2014 Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) strategy. These strategies have been further operationalized through regional maritime codes of conduct such as the Djibouti Code of Conduct (signed in 2009) and Yaoundé Code of Conduct (signed in 2013).

Pirates holding the crew of the Chinese fishing vessel FV Tianyu 8 guard the crew Monday, Nov. 17, 2008, as the ship passes through the Indian Ocean.

The Djibouti Code was the first major attempt by African states to establish a cooperation mechanism to counter piracy and armed robbery against ships in the western Indian Ocean. This was achieved through the establishment of three Information Sharing Centers in Sana’a (Yemen), Mombasa (Kenya), and Dar es Salaam (Tanzania). The code also established the Djibouti Regional Training Center for the sole purpose of training and building capacity in law enforcement activity on the sea. Participating states are creating a counter-piracy architecture to improve communication and coast guard capabilities and enhance the deterrence, arrest, and prosecution of pirates.

The establishment of such infrastructure benefitted from similar ones in ECCAS, which set up a center to coordinate maritime safety and security activities across zones A, B, and D, extending from Angola to Cameroon and including the navies of Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and São Tomé and Príncipe.

Q: What are the main obstacles and what are some key lessons?

AM: The key challenge is continuing to shift the mindsets of government officials to recognize the vital importance of the maritime domain as part of a comprehensive national security strategy. Second, while the AU has developed an overarching architecture for regional maritime security, much more needs to be done to create, resource, and strengthen the institutions called for in the African Integrated Maritime Strategy and its various protocols.

There is also need for better prioritization, mobilization, and alignment of resources, particularly in terms of technology and communications, establishment and coordination of coast guards, personnel training, and the sharing of maritime intelligence and surveillance. In addition, more needs to be done to fully operationalize the shared maritime domain awareness centers such as the ones envisioned in the SADC maritime strategy.

A number of key lessons have been learned. First, no single country, no matter how well resourced and equipped, can combat maritime security threats or exploit opportunities on its own. This is why moves to operationalize regional maritime zones are so crucial. Second, as the Djibouti Code of Conduct arrangements suggest, a common framework for national maritime assets is key. It would make little sense for one country to invest in naval power projection capabilities while its neighbors invest in coast guard-type capabilities. Coast guards are often more appropriate to combating Africa’s maritime threats, so it makes better sense to invest in them jointly as part of a coordinated regional strategic framework. Third, to be effective in law enforcement, regional maritime protocols must be domesticated into national legal frameworks.

For too long the maritime domain has been treated as an afterthought. That is now changing, thanks to growing political will to address maritime threats and opportunities. This will ultimately enhance maritime safety and security in the strategically vital western Indian Ocean.

Africa Center Experts

- Raymond Gilpin, Dean of Academic Affairs

- Benjamin Crockett, Associate Dean of Academic Affairs and Professor of Practice

Additional Resources

- Adeniyi Adejimi Osinowo, “Combating Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea,” Africa Security Brief No. 30, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 2015.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “National Maritime Security Strategy Toolkit” June 27, 2016.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Maritime Safety and Security: Crucial for Africa’s Strategic Future,” Spotlight, March 4, 2016.

- Liesel Louw, “What Does Ensuring SADC’s Maritime Security Mean for South Africa?” Institute for Security Studies, April 16, 2014.

- Assis Malaquias, “Africa Is an Island,” presentation on maritime safety and security at the Seminar on African Contemporary Security Issues, December 19, 2016.

- Augustus Vogel, “Navies versus Coast Guards: Defining the Roles of Maritime Security Forces,” Africa Security Brief No. 2, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 31, 2009.

- Augustus Vogel, “Investing in Science and Technology to Meet Africa’s Security Challenges,” Africa Security Brief No. 10, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 28, 2011.

More on: Maritime Security Regional and International Security Cooperation Food Security