Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Summary

Piracy, illegal fishing, and narcotics and human trafficking are growing rapidly in Africa and represent an increasingly central component of the threat matrix facing the continent. However, African states’ maritime security structures are often misaligned with the challenges posed and need coast guard capabilities and an array of intra-governmental partnerships.

A South African frigate. (Photo: Pixabay)

Highlights

- Maritime security challenges in Africa are growing rapidly and represent an increasingly central component of the threat matrix facing the continent.

- African states struggle to meet these threats because their maritime security structures are misaligned with the challenges posed.

- Redressing this misalignment will require valuing the coast guard capacity demanded by these threats and constructing the array of intragovernmental partnerships needed to be effective in combating these threats.

Africa’s Growing Maritime Security Challenge

In February 2008, the Nigerian Trawler Owners’ Association (NTOA) called in its fishing vessels and refused to go to sea. The previous year had been a tough one. A reported 107 armed robberies had reduced the fishing fleet from 250 trawlers in 2003 to 170 by the end of 2007. January 2008 started off even worse, as NTOA ships suffered another 50 attacks and 10 murders in that month alone. Well documented among NTOA’s numerous complaints was that when an attack occurred, there was nobody to call for help.

A variety of recommendations by NTOA have evolved into a campaign to convince the government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria to establish a coast guard. The main argument is that the Nigerian navy—one of the most sophisticated navies in Africa, with a demonstrated capability to sail to Europe and South America—is not designed to combat maritime armed robbery and piracy. It is essentially a blue water navy, one that was capable of shelling rebel forces in Sierra Leone in the 1990s but is powerless to deal with local crime.

Nigeria’s experience reflects Africa’s maritime security environment. Of the 33 independent maritime nations in sub-Saharan Africa, only five—Cape Verde, Liberia (when legislation is finalized), São Tome and Principe, the Republic of Mauritius, and the Republic of Seychelles—have maritime forces that identify themselves as coast guards rather than navies. Yet Africa’s maritime security challenges are most often comprised of threats such as illegal fishing, narcotrafficking, and maritime disaster response—threats requiring the technical skills and collaborative relationships with civilian organizations typical of a coast guard.

“Adapting Africa’s maritime security capacity to meet these emerging challenges is an escalating priority with more serious implications for the continent and global security than is commonly recognized.”

Properly meeting these threats is vitally important to Africa: illegal fishing undercuts Africa’s economic development and exacerbates its food security challenges; piracy makes badly needed trade and investment in Africa more risky and expensive; the continent is becoming an increasingly active drug trafficking hub; the growing drug trade, in turn, is giving international criminal syndicates a foothold within certain African governments, weakening their ability to address other national priorities; and illegal commerce (such as oil bunkering, transport of counterfeit materials, and theft) impacts legitimate businesses and world markets. In short, many of Africa’s emerging threats arrive by sea.

Africa’s maritime security also has direct implications for the rest of the world. In 2007, an estimated 60 percent of the cocaine in the European market (valued at $1.8 billion) had passed through West Africa. Many of these drugs arrive in Africa in cargo ships, are landed in small boats and fishing vessels, and often shipped abroad in the same. Much of the $775 million in smuggled cigarettes and the approximately $438 million in counterfeit malarial medication that transit West Africa annually is seaborne. Illegal fishing, primarily by European, Asian, and African commercial vessels, is estimated to cost sub-Saharan Africa more than $1 billion per year.

Adapting Africa’s maritime security capacity to meet these emerging challenges is an escalating priority with more serious implications for the continent and global security than is commonly recognized.

Navy versus Coast Guard

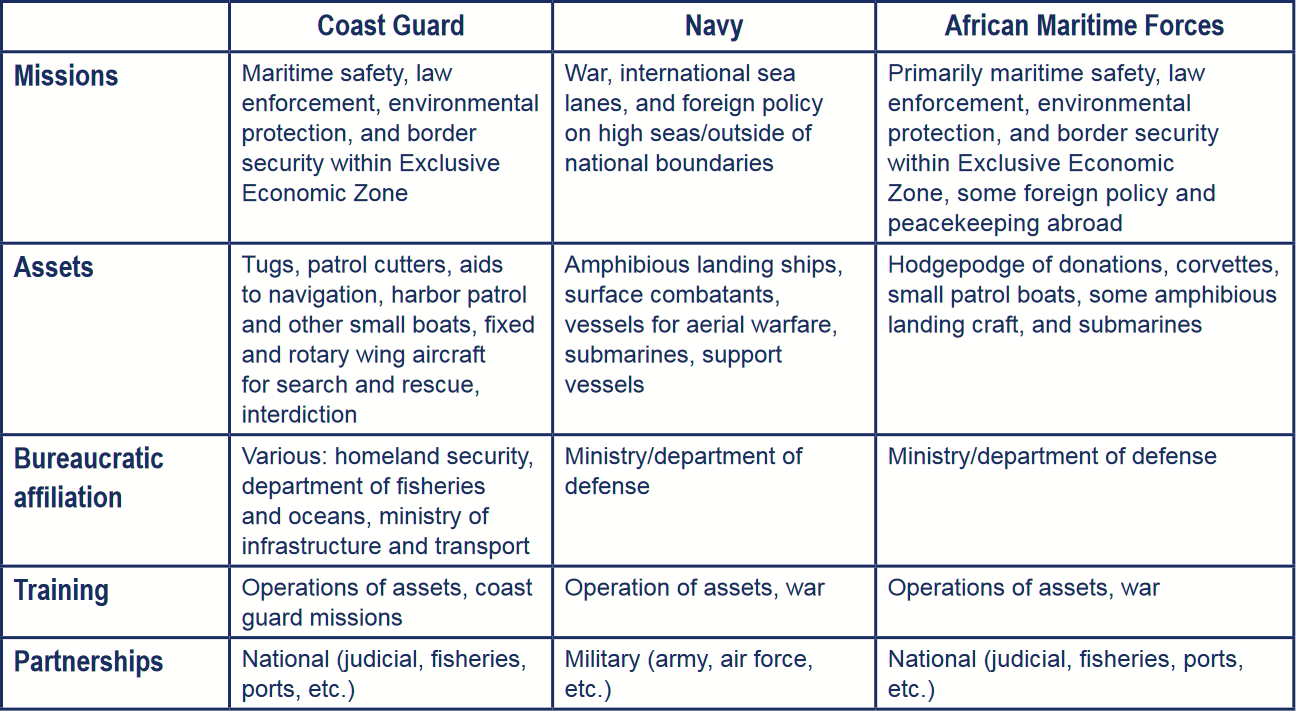

Navies and coast guards play fundamentally different, though complementary, roles. Navies are international operators primarily concerned with national defense. Coast guards, on the other hand, function more as maritime police, preventing crime and promoting public safety. Analyzed below are five dimensions that differentiate the two forces. While not universally applicable, they provide a useful framework for assessing the roles and contributions of African maritime security forces.

Mission Sets and Locations

Navies in a traditional sense are important instruments for implementing foreign policy: they fight a nation’s wars and project power beyond a state’s territorial boundaries. During times of peace, navies also play strategic and diplomatic roles. For example, President Theodore Roosevelt dispatched the “Great White Fleet” around the world in 1907 to demonstrate the reemergence of the U.S. Navy as an important international player. In 2009, the Russian navy and China’s Peoples’ Liberation Army Navy held joint exercises in the Gulf of Aden. And the U.S. and many European navies regularly provide training for navies in Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

In the African context, foreign policy as a “navy” function is also demonstrated by deploying ships abroad on diplomatic and exercise-related port visits, such as recent visits by the South African navy to China, Brazil, and the United Kingdom or by the Nigerian navy to Brazil and the United Kingdom. Peacekeeping missions are also performed, as in Liberia and Sierra Leone by the Senegalese and Nigerian navies, respectively. Unfortunately, operational limitations prevent most African navies from executing international at-sea missions. Instead, they primarily meet their foreign policy obligations by serving as military diplomats at ceremonial functions and international meetings.

However, these “navy” activities represent only a small fraction of the commitments African maritime security forces must meet. A much larger part of their mission set is coast guard in nature and relates to law enforcement, environmental protection, and maritime safety obligations that occur within a nation’s territorial waters (within 12 nautical miles of the coastline) and exclusive economic zone (EEZ; waters within 200 nautical miles of the coastline). African maritime security forces enforce laws combating the aforementioned illegal traffic in narcotics, cigarettes, fish, and other contraband that passes inside their EEZ, as well as support environmental protection efforts that prevent illegal fishing, dumping of waste, and other forms of destructive resource exploitation. They are also called on to respond to maritime disasters. For example, the Kenyan navy saved some passengers and recovered the remains of others after the Mtongwe passenger ferry sank in 1994, and the Senegalese navy was criticized for its lack of response to the sinking of the MV Joola in 2002 (where as many as 1,800 lives were lost).

Assets

The mission of maritime security forces is reflected in the vessels it operates. Navies, which sail international waters, are trained to perform war functions and carry troops and equipment. Amphibious landing ships will carry personnel and equipment for beach assaults, while surface combatants (such as frigates, cruisers, and destroyers) provide strike and logistics capabilities.

Given its law enforcement, environmental protection, and safety roles, a coast guard fleet must be capable of performing search and rescue (SAR) activities and patrolling coastal waters, lakes, and rivers. Their vessels include cutters, tugs, buoy tenders, and icebreakers, as well as small boats for harbor patrols and interception activities close to shore. Coast guard fleets do not include vessels as big as the larger naval platforms, but their cutters and enforcement platforms are equivalent in size and capability to some naval surface combatants like frigates.

Characterizing African maritime security forces according to this dichotomy is difficult. Most nations have a variety of inflatable boats and corvettes that can comfortably operate at sea for 1 to 3 days (that is, performing coast guard functions), but also have ships with navy characteristics, such as the landing craft owned by Senegal and Nigeria or the submarines operated by the South African navy. The assets African maritime security forces operate are frequently a mix of designs and capabilities and reflect the vagaries of international donations and purchases. For example, the Ghana navy operates buoy tenders received from the U.S. Coast Guard through the Excess Defense Articles program. The Nigerian navy has purchased a variety of vessels from British, French, German, Italian, and other shipbuilding companies. And the Mauritian coast guard’s flagship was built in Chile.

This situation has created a conundrum. Maritime assets are prohibitively expensive to purchase, operate, and maintain, and maximizing their efficient use is critical. But African states lack the shipyards to build their own vessels and frequently depend on donations or purchases of used equipment. Even with extremely limited budgets, they rely on assets with hard-to-find replacement parts, operate a fleet of vessels with minimal interoperability, and use equipment whose operation is economically inefficient for the missions at hand.

Institutional Affiliation

Navies are military organizations that report to a ministry or department of defense. Coast guards, in contrast, typically function as paramilitary arms of civilian institutions because of their diverse responsibilities related to issues like safety and regulation of commerce. For example, the U.S. Coast Guard reports to the Department of Homeland Security (except in times of war), the Canadian coast guard reports to the department of fisheries and oceans, and the Malaysian coast guard is a branch of the civil service. When there is no cohesive mandate, many coast guard duties will be divided between a variety of services, such as in South Africa, where eight different agencies perform coast guard functions.

“Conventionally, a navy will train its sailors primarily in the skills needed to perform foreign policy missions and defend the nation, whereas coast guard training will prioritize such things as fisheries management, law enforcement, and search-and-rescue.”

Since African maritime security forces (even those that identify themselves as coast guards) universally report to ministries of defense, institutionally they are all effectively “navies.” In many cases, this structure was initiated by colonial bureaucracies responsible for defending empires. The Nigerian navy, for example, was created in 1956 by an act of the British Parliament. The predecessors of the Ghana and Kenyan navies were the Gold Coast Naval Volunteer Force and the Royal East African Navy, respectively. In the postcolonial period, the rationale for these forces has shifted from serving the needs of colonial powers with global ambitions to burnishing national prestige. The Nigerian navy, for example, asserts in its official Web site that Nigeria deserves “a Navy [in] which we can be justifiably proud and which is worthy of this great country” and that it would be inadequate for Nigeria to have “a token Navy which is capable of plying on our lagoon and River Ogun and no more!”

This perspective is emblematic of the strong institutional impulse by Africa’s navies to maintain distinctly military structures and identities. Because these organizations conceptualize themselves to be purely military, they naturally gravitate to the “navy” mission sets identified above, even if these missions are objectively not as important to the immediate security needs of the country. Leaders prioritize national defense mandates, and operational emphasis is given to performing foreign policy missions rather than law enforcement, environmental protection, and maritime safety.

Training

Outside of basic training, mission-related training will differentiate between a navy and coast guard. Conventionally, a navy will train its sailors primarily in the skills needed to perform foreign policy missions and defend the nation, whereas coast guard training will prioritize such things as fisheries management, law enforcement, and SAR.

As a general rule, African maritime security forces are trained as navies and do not receive adequate training in the numerous coast guard missions with which they are tasked. Much of their training is focused on core seamanship and internal operations. When training abroad, for example, African officers typically visit naval colleges and receive military officer training. While they can get underway and stop suspect vessels, many African navies lack the nuanced and specific skills needed to perform their missions. Examples of these skills include crime scene investigative techniques during drug seizures, an up-to-date understanding of legal fishing-net mesh sizes, and appropriate search patterns when looking for a vessel lost at sea.

Partnerships

As a military organization, a navy maintains its most active partnerships with other military branches (such as an army or air force). On the other hand, most of a coast guard’s collaborations are with civilian organizations. These partnerships include departments of fisheries, gendarmeries and maritime police forces, port authorities, environmental protection agencies, and international maritime regulatory bodies.

The issue of partnerships is emblematic of the challenges that African maritime security forces face. They are uniformed and identify themselves as military organizations, but to perform their missions successfully, they must rely on relationships with civilian organizations. Unfortunately, when these relationships are not cultivated, they can quickly degenerate into mistrust and acrimony and limit the ability of African maritime security forces to perform their missions effectively. They may, for example, stop a vessel suspected of illegal fishing but not have a fisheries representative on board to help define the law. Notable exceptions exist. Senegalese naval officers are ensconced in the Fisheries Directorate’s surveillance unit and also pilot the national oceanographic research vessel. Likewise, the Nigerian navy and the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency collaborate on electronic surveillance. These partnerships have proven to be an important mechanism for effectively utilizing scarce financial resources and maintaining skills important to the security challenges faced by these two countries. Pooling resources prevents duplications of effort and maximizes the efficiency of lean budgets.

A Way Forward

African maritime security forces are currently misaligned to meet the security threats they face. They have navy bureaucratic affiliations and training programs but have a predominance of coast guard missions, operate in coast guard zones, and require coast guard partnerships (see table). Accordingly, they are not efficiently organized and trained to meet their challenges. They are also hampered by their dependence upon the poorly matched foreign equipment they purchase or are given. Inefficiency and small budgets reinforce each other, allowing maritime security challenges to remain substantially unchecked. Billions of dollars of fish are stolen every year from a continent facing some of the world’s highest levels of malnutrition. International drug syndicates are gaining a foothold among what are already some of the world’s most fragile states.

Reconciling the Disconnect

Match Assets to Needs.

African states naturally have the best vantage point for planning how to address their maritime security challenges. Whether a maritime security force is considered a “navy” or a “coast guard” is secondary. More important is properly identifying threats and matching resources to meet those threats. Every bureaucracy must conduct a similar planning process. For Africa, a series of threat assessments would be highly beneficial, as no one really knows what is going on in African waters. Many of the statistics frequently advanced on drug traffic, illegal fishing, illicit commerce, and other prohibited activities are at best educated guesses. It is also not known how much activity is occurring relatively close to shore (within territorial waters) or over the horizon in EEZs. A comprehensive survey using satellite imagery to quantify ship traffic would be a good place to start.

Build More Interministerial Collaboration.

Greater intragovernmental partnership and coordination are needed to achieve successful “coast guard” solutions, especially given the military identity of African maritime security forces. A number of countries have recently initiated the process of connecting the variety of agencies responsible for maritime security operations under a single coordinating body. Senegal, for example, has La Haute Autorité Chargée de la Coordination de la Sécurité Maritime, de la Sûreté Maritime et de la Protection de l’Environnement Marin (The High Authority Charged with Coordination of Maritime Security, Maritime Safety, and Protection of the Marine Environment). Ghana has the Ghana Maritime Authority. And Nigeria has the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency.

These bodies help coordinate activities of navies, coast guards, harbor authorities, transport and commerce ministries, fisheries agencies, and generally anyone involved with maritime security. Naturally, there is tension regarding the balance between the coordinating bodies’ role in organizing other agencies and the former’s right to mandate certain actions from a position of authority. Striking a balance will vary from country from country, but efforts should be made to strengthen these bodies and define their roles with the full support of other maritime organizations.

Engage in Capacity-building.

Various countries, including the United States, several European nations, and China, are investing resources to help strengthen Africa’s maritime security. These supporting countries should work to ensure that their maritime security capacity-building programs help redress the misalignments noted above. Otherwise, this support risks widening the imbalance. The U.S. Navy, for example, has considerably more resources than the U.S. Coast Guard for maritime security capacity-building because it has a more entrenched mandate for investing resources in operations abroad. This is true even though the U.S. Coast Guard’s mission and skill set might appear to be a more natural fit with Africa’s maritime security challenges. Nevertheless, the following are some suggestions for the United States and international partners:

- Differentiate between support that focuses on core aspects of African naval capacity and that which directly concerns specific maritime security threats. This strategy will help bridge the current disconnect between training and mission requirements in Africa.

- In both training and provision of equipment, be responsive to specific maritime security challenges that African states identify. Maritime security in Africa will not be advanced without enthusiastic and self-motivated support from African states themselves.

- Match donor interagency partnerships with what African maritime security forces must build. For example, when operating in U.S. waters, the U.S. Coast Guard partners with numerous agencies. These partnerships can be recreated to engage the required spectrum of African agencies. In this way, expertise can be properly paired within a unified approach.

Africa is confronted with a variety of maritime security challenges, many of which require “coast guard” operations. These challenges are growing exponentially and, if left unchecked, could cripple Africa’s recent development progress and movement toward democracy. They also threaten to exacerbate the level of instability that exists on the continent. Too often, Africa’s maritime security forces are not optimally positioned to meet these challenges. A disconnect between how these organizations identify themselves and the missions they face indicates that African states need to better align their national maritime security plans, partnerships, and assets. International partners, meanwhile, must calibrate their support accordingly.

If African states can better align their maritime security capacities to their challenges, then Nigerian trawlers will have someone they can radio the next time they are faced with armed robbery at sea. In the process, Africa’s 26,000 kilometers of coastline can again be a source of prosperity rather than vulnerability.

Helmoed Heitman is a defense consultant, correspondent for Jane’s Defence Weekly, and a member of the Vision 2020 project team of the South African Army, from which he retired as a major in 1996.