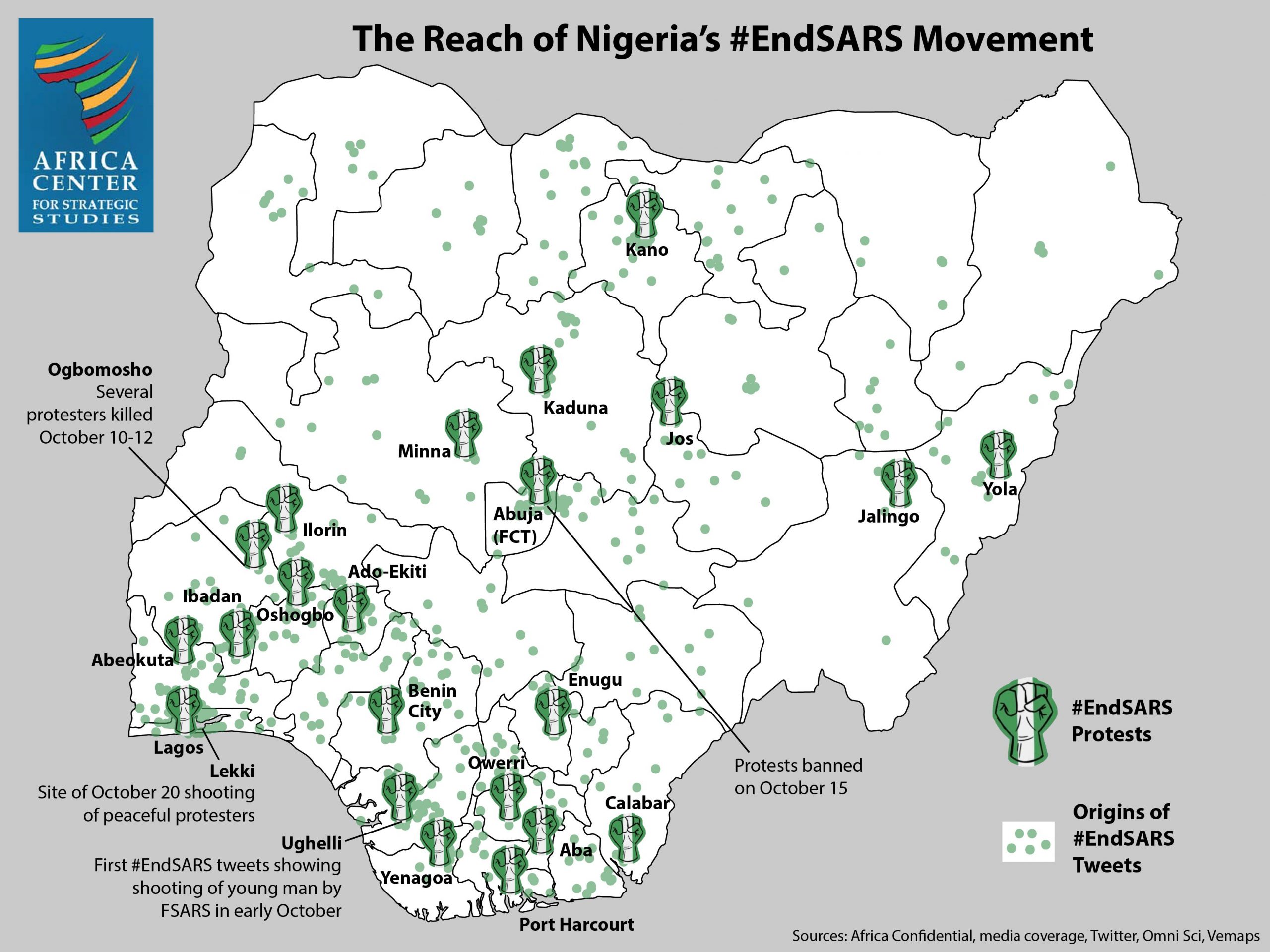

The carjacking and shooting of a young man in Delta state by Nigeria’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) police officers in October sparked widespread public outrage. Almost immediately, many young Nigerians began sharing their anger and their own experiences with SARS on social media, calling themselves the Soro Soke (“the Speak Up”) generation. Within days, the #EndSARS hashtag became a movement that gave voice to Nigerians fed up with the violence, extortion, and impunity of the notorious police unit. Over the following weeks, numerous protests and vigils were held across Nigeria, transcending the country’s religious, ethnic, and political divides. Nigerian Police

The protests came to a head on October 20 when Nigerian security forces fired on protestors staging a sit-in on a toll road in the Lekki area of Lagos. Twelve people were killed, adding to dozens who have died across the country during the protests. Witnesses claim army and police officers were responsible for the unprovoked Lekki shooting. The incident was added to an inquiry established to look into the SARS abuses.

The #EndSARS movement is driven by deep discontentment and systemic problems perceived by Nigerian citizens. Surveys show that Nigerians report very low levels of trust in the police—and that a third of them have paid or been asked to pay a bribe to police. Experts describe how some police forces have been commercialized to serve the interests of politicians and rich individuals rather than to protect the public. Nigeria’s National Human Rights Commission reported that security forces extrajudicially killed at least 18 people while enforcing the country’s COVID-19 lockdowns earlier this year. Incidents of police violence are common in the national news.

Partners West Africa Executive Director Kemi Okenyodo has long called for police reform in Nigeria. The Africa Center spoke to her about the meaning of the #EndSARS movement and what it portends for police reform in Nigeria.

* * *

What’s motivating Nigeria’s #EndSARS protests and why have they focused on the Anti-Robbery Section of the police force?

Armed robbery is one of the most serious security threats facing Nigeria. Over the years it’s become more violent and widespread across the country. The State Anti-Robbery Section—part of the State Criminal Investigation Departments within the 36 state commands and FCT (Federal Capital Territory)—has long been ineffective due to the perennial challenges facing the Nigerian Police Force (NPF). These include undertrained personnel, lack of funding, inadequate equipment, and weak supervision and accountability, to mention a few.

An #EndSARS protester in Lagos. (Image: Kaizenify)

Rather than address these challenges, the NPF, in its wisdom, set up the Federal Special Anti-Robbery Squad (FSARS), which operates directly under the Inspector General of Police, with an Abuja-based Commissioner of Police overseeing their activities. FSARS was established across the 36 states and FCT. They do not report to the States’ Commissioners of Police.

When it was created in the 1990s, the FSARS team was said to be effective and busted armed robbery operations across the country. However, over time, the perennial challenges of Nigeria’s police institutions caught up with them. FSARS engaged in human rights violations particularly torture, extrajudicial killings, and disappearances of suspects in their custody, among other allegations.

Youth are particularly targeted, mainly because of their naiveté and lack of knowledge of their rights as citizens. Police officers, meanwhile, often hold unsupported stereotypes against youth—tagging them as criminals, internet fraudsters, or armed robbers—because of dreadlocks, ripped jeans, tattoos, flashy cars, or ostensibly expensive gadgets like smart phones. The targeting has not been gender-specific, so young women have also fallen victim.

There has been a series of efforts to reform FSARS/SARS over the years, however none has worked so far. They have been disbanded several times, however, have always found their way back into existence.

Now, Nigerians are protesting to put an end to SARS’ human rights abuses and lack of accountability.

Why is the movement resonating with so many Nigerians?

“The movement resonates with so many Nigerians because SARS depicts everything we are dissatisfied with about the state of our governance system as a whole.”

The movement resonates with so many Nigerians because SARS depicts everything we are dissatisfied with about the state of our governance system as a whole—impunity, corruption, nepotism, and a lack of transparency and effective reforms. These problems are particularly motivating young Nigerians because they form a critical mass of the country’s population (65-70 percent) and many have had experiences being targeted and harassed by these police officers.

How has the government’s heavy-handed response affected the protesters’ demands?

Most of the protesters are fatigued by the killings that have taken place across the country and by the hijacking of some of the protests by bad actors (rioters, looters), allegedly paid by politicians and government agents to alter the narrative of the protests and to give a reason to deploy security forces. Eyewitnesses have reported that some of these hoodlums were being protected by police officers and were the same young men (“area boys”) mobilized by various political landlords in Lagos State to intimidate opponents during elections. Powerful individuals and politicians are resisting police reform because they would prefer to have the police in their pockets, serving their own interests rather than the public’s.

After the attacks by the security forces in places like Lekki, most of the protesters have been forced to flee, regroup, and re-strategize. That is where things stand now. There is some ongoing coordination among activists across the country—organizing to monitor the panels of inquiries, support victims, and guide protesters in putting forward their claims properly. President Buhari’s speech on October 21 addressed—albeit a bit hollowly—some of the demands: reiteration of the disbandment of SARS and the approval of a revised welfare and salary package for the police to improve professionalism, which has been pending since 2018. Some of us are looking at how the Police Act 2020 can be used to facilitate the reform process.

However, reports that Buhari’s administration is now aggressively targeting protest leaders by freezing their bank accounts, confiscating travel documents, and detaining them despite promises of dialogue doesn’t show good faith on the part of the government. It gives the impression that the steps being taken towards reforms might not be backed with sincerity. This would only increase the divide and lack of trust between the government and its citizens.

#EndSARS protesters take a knee in Lagos. (Image: TobiJamesCandids)

What concrete steps should the government take in engaging protesters and in developing policies for lasting police, military, and governance reforms?

There are numerous reports from different presidential panels of inquiry on this subject matter. The government should synthesize the recommendations from these reports and IMPLEMENT THEM!

“Reforms have also called for permanently disbanding FSARS and preventing similar forces from replacing them…this will require decentralizing policing in Nigeria…which would allow for more accountable community policing.”

These recommendations include prioritizing improved recruitment, professionalization, and accountability mechanisms through merit-based appointment, promotion, and removal processes, as well as improving the working conditions of the police through better pay and benefits.

Transparency is an initial step as recommended reforms from previous reports have never been made public despite the 2012 Freedom of Information Act, which has been eclipsed by the Official Secrets Act. This has allowed the NPF to continue withholding information that would allow for investigations and the identification of paths to reform.

Reforms have also called for permanently disbanding FSARS and preventing similar forces from replacing them. This will require decentralizing policing in Nigeria. Doing so would allow for more accountable community policing not beholden to far-away decisions and political interference.

* * *

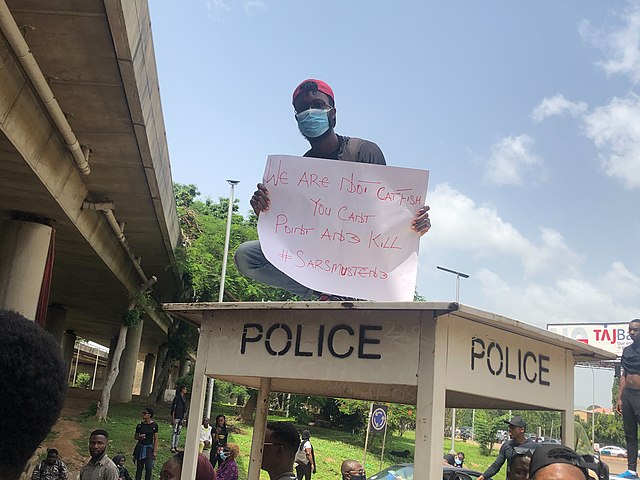

An #EndSARS protester above a police stand in Abuja. (Image: Aliyu Dahiru Aliyu)

In a separate conversation on what comes next, Dr. Sharkdam Wapmuk, Associate Professor at the Nigerian Defence Academy, offered an agenda for reform priorities:

- Rebuilding trust. The government needs to do more to earn the trust of Nigerian citizens. Measures put in place by the government to address shortcomings in the policing system, military, and governance must be seen to be sincere.

- More inclusive oversight. The Judicial Panel of Inquiry set up by some states to probe police brutality should be inclusive of critical stakeholders and not only government nominees. It would be more fruitful, moreover, if the Panel serves as a sort of Truth and Reconciliation Body, thus serving the purpose of healing and reconciliation. This could also provide a paradigm shift and foundation for building a “new” relationship between the police and citizens. The police need the people, and the people dearly need the police. Hence the urgent need for community policing.

- Independent investigations into police abuses. To end police impunity, the government needs to establish an independent body with a mandate to consistently investigate and report crimes committed by the police and other security bodies, including extortion, unlawful detentions, corruption, and brutality. These reports then need to be enforced with strict penalties for proven cases. This body should include representatives of civil society organizations.

- Holistic police reform. It is important not to over-generalize. There are many good police officers. Yet good men and women recruited into the police force can easily turn bad due to poor remuneration and overall poor conditions of service. Generally, police in Nigeria face serious challenges such as poor funding, shortage of personnel, dilapidated housing units and offices, poor equipment and vehicles, and lack of maintenance structures. Reform of the police will not be complete without addressing these challenges.

- Focus on citizen security. The reform of Nigeria’s security architecture, particularly the relationship between citizens and security agencies, is long overdue. There should be training and retraining of the security agencies on issues of citizen protection, human rights, relations with citizens, and building community trust.

Additional Resources

- Chiedo Nwankwor and Elor Nkereuwem, “How Women Helped Rally Mass Protests against Nigeria’s Police Corruption,” The Washington Post, November 4, 2020.

- Krystal Strong, “The Rise and Suppression of #EndSARS,” Harper’s Bazaar, October 27, 2020.

- Kwesi Aning and Joseph Siegle, “Assessing Attitudes of the Next Generation of African Security Sector Professionals,” Africa Center Research Paper No. 7, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 1, 2019.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Security Priorities for the New Nigerian Government,” Spotlight, February 25, 2019.

- Oluwakemi Okenyodo, “Governance, Accountability, and Security in Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 31, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 21, 2016.

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Research Paper No. 6, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 31, 2014.

- Steven Livingston, “Africa’s Information Revolution: Implications for Crime, Policing, and Citizen Security,” Research Paper No. 5, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, November 30, 2013.

More on: Nigeria Policing Rule of Law