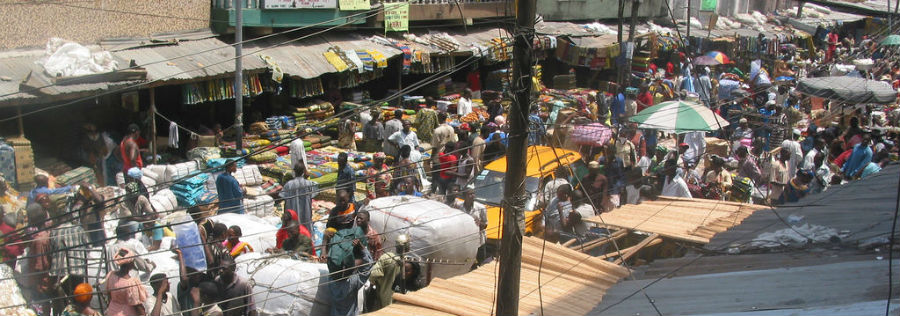

A market in Lagos, Nigeria. (Photo: Zouzou Wizman)

On February 23, 2019, Nigerians voted in their sixth presidential election since the transition to civilian rule in 1999, reelecting Muhammadu Buhari to a second term. Many see the progress Nigeria has made in institutionalizing democratic norms as a bellwether for other African countries. At the same time, Nigeria faces an array of security challenges that have caused thousands of deaths and led to the displacement of 2 million people while inhibiting the country’s economic development. As President Buhari gets set to begin his second term, Nigeria’s security landscape will demand significant executive attention and political capital.

To provide some perspective on the host of security challenges facing the Buhari government over the next 4 years, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies spoke with five Nigeria experts for their assessments:

- Dr. Gani Yoroms, Senior Fellow at Nigeria’s Defense College

- Dr. Sharkdam Wapmuk, Senior Research Fellow at the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs

- Ms. Oge Onubogu, senior program officer at the United States Institute of Peace

- Dr. Ernest Ogbozor, Visiting Scholar at the Center for Peacemaking Practice at George Mason University

- Dr. Mark Duerksen, scholar of urban planning and human security from Harvard University’s Department of African and African-American Studies.

What do you see as the top security priorities facing the next Nigerian administration?

Onubogu: Nigeria’s top priority should be national unity. All the conflicts that affect Nigeria, whether it is Boko Haram, farmer-herder violence, or sectarian violence in Biafra and the Niger Delta, are rooted in the country’s deepening divisions. The use of inflammatory rhetoric during campaigns is one indicator of these widening cleavages. It also underscores the willingness of some political leaders to exacerbate grievances for political purposes. Nigeria sits on many fault lines—regional, religious, and ethnic—and it will be critical for the next administration to bring communities together, advance reconciliation and local development, and promote policies of inclusion.

Citizens have become much more knowledgeable about the electoral process and better skilled and resourced in agitating for political change.

Nigerians will have an important role to play in holding the next administration accountable and ensuring that it prioritizes national unity and social cohesion. Since 1999, citizens have become much more knowledgeable about the electoral process and better skilled and resourced in agitating for political change. The number of political parties that participated in the 2019 election, coupled with the enthusiasm that we saw on the ground and the vigorous campaigns, indicates that Nigerians are capable of focusing on important issues and pressing their demands. This makes me optimistic that civil society can emerge as a strong voice to articulate priorities and keep the government on its toes.

Ogbozor: I think institutional reforms should be the top priority for the next administration because without them, Nigeria will continue to rely on policy ideas that have not been successful in stabilizing the country. First, the security services need to better reflect the country as a whole so that citizens can feel included. Right now, there is a widespread perception that the top positions in the military, intelligence, police, and indeed the rest of the federal government are dominated by northerners. This does not bode well for national unity, or for public confidence in the government’s ability to provide security.

Second, appointments to key positions are generally not made on merit, but rather along ethnic, religious, and regional lines, and this has further undermined the government’s image. Third, politicians at the federal, state, and local levels continue to be implicated in fanning conflicts, manipulating social and political tensions, or simply failing to respond to crises. Many victims of the farmer-herder violence in the Middle Belt, for instance, complain that individuals in the federal government, many of them ranchers, have turned a blind eye to the attacks carried out by Fulani herdsmen against farmers. Indeed, recent field research is showing that the lack of political will by the government to arrest and adequately punish offenders is one of the factors fueling farmer-herder violence in Nigeria.

A Nigeria home burned in suspected herder attack in May 2016. (Photo: VOA/C. Stein)

Wapmuk: The next government should prioritize the threats posed by Boko Haram terrorism, escalating farmer-herder conflicts, and the growing spate of kidnappings, armed robberies, religious clashes, and the proliferation of small arms. None of these threats are new, but their intensity and frequency appear to have increased in recent years. The government also needs to pay attention to the spread of ethnic-based militias, vigilante groups, and separatist movements that have continued to afflict Nigeria since democratic rule returned in 1999. Some groups of note include the O’odua People’s Congress (OPC), Arewa People’s Congress (APC), Igbo People’s Congress (IPC), Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), Niger Delta People’s Volunteer Force (NDPVF), and the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB). The sectarian violence perpetrated by these and other groups represent grave threats to national security, even though Boko Haram tends to dominate the news.

Duerksen: The next administration will face several acute security challenges, including the ongoing Boko Haram insurgency in the northeast, Fulani herdsmen attacks in the Middle Belt states (particularly Benue, Plateau, Kaduna, and Taraba), and the activities of rebel groups (including the Niger Delta Avengers and Biafra separatists) in the south and southeast. I view these as Nigeria’s top priorities because of the daily violence and terror these groups inflict and because they pose existential threats to Nigerian sovereignty. However, these issues have arisen and festered as a result of long-term structural factors, particularly extreme poverty and a lack of education opportunities. Nearly half of Nigeria’s 190 million citizens live on less than $1.90 a day, despite the country’s $2,000 GDP per capita. About 10 million children are out of school in Nigeria, more than in any other country in the world.

These challenges are rooted in an enduring lack of accountability and inclusivity in the Nigerian state, its heavily oil-dependent economy, and rampant impunity. The land grabs by powerful Lagos families, reported killings of Shiite marchers in Abuja by the Presidential Guard Brigade, and rampant embezzlement in the military are a few examples of what can go wrong when impunity is allowed to continue. Addressing graft and impunity at the highest levels of the government, military, and civil service, redistributing funds, and reinvigorating fundamental rights for the people of Nigeria should be the top security priorities for the next administration.

Yoroms: The farmer-herder violence has not been handled well, and it seems there is no strategy in place. If we compound this with the ongoing Boko Haram violence and the growing spate of kidnappings and political killings, it becomes clear that the next government will have a lot on its plate. Nigeria’s next administration will need to undertake serious political and security reforms and forge closer regional security cooperation. It will also need international support. Defense and security sector reform should underpin the needed revitalization. All efforts that have been undertaken in this regard since 1991 have been mere window dressing, and this partly explains the rampant graft in the sector, cases of indiscipline, and abuse of human rights, especially during security operations.

What are some of the emerging threats facing the country that are not receiving enough attention?

Duerksen: Urban density has meant better access to health and education services for many, yet the emerging threats associated with rapid urbanization have often been overlooked. Nearly every acute security challenge in Nigeria has been exacerbated by urban conditions. Boko Haram has targeted vulnerable urban markets and bus depots in Maiduguri and Abuja. Crowded cities like Port Harcourt and Lagos present tactical challenges to addressing outbursts of secessionist and sectarian violence. Peri-urban sprawl in the Middle Belt has impinged on Fulani grazing lands. Nigeria’s housing deficit is at least 17 million units (affecting over 70 million Nigerians), with many other residents in cities like Lagos living in inadequate or insecure shelter. Numerous studies have connected the importance of adequate shelter to the life outcomes of children, making housing insecurity a critically overlooked threat in a country with 90 million people under the age of 14.

A street in Lagos, Nigeria. (Photo: Zouzou Wizman)

Wapmuk: The farmer-herder violence has not received enough attention. Migrations by Fulani herdsmen from the north to the south are increasingly difficult due to depleted grazing lands, growing populations, and the rapid growth of farming settlements along established cattle routes. Herders are also spending more time in wetlands and opting to establish permanent settlements, which often brings them into conflict with other communities. The massive population displacements resulting from these conflicts has created another threat, that of food insecurity. The government’s policy is to reduce the food import bill and diversify the economy, but it has yet to appreciate the full impact of the farmer-herder violence on food production. One study notes that Nigeria loses $13.7 billion in revenue annually due to farmer-herder conflicts in Benue, Kaduna, Nasarawa, and Plateau states, costing these four states on average 47 percent of their internally generated revenues, mostly from agriculture. Nigeria’s farmer-herder violence simply cannot be ignored anymore.

Yoroms: More than 1,300 Nigerians died from the farmer-herder conflicts in the first half of 2018. While considerably more prominence is given to the Boko Haram menace, more attention needs to be paid to addressing farmer-herder tensions. The Boko Haram insurgency has also overshadowed other deadly groups such as those in the Niger Delta, as well as a host of other armed groups, including those demanding secession.

The next administration should make police reform a priority within the larger defense and security sector review.

Onubogu: In the past decade, we have witnessed the steady erosion of Nigeria’s policing capacity as the government has mostly relied on the military to respond to conflicts. This could emerge as a threat to whole-of-government efficiency in providing security. The persistence of the Boko Haram insurgency has meant that the armed forces are overstretched, and yet they are also being used in roles and functions normally reserved for the police. Typically, the military will push out Boko Haram militants from an area, but local police forces are inadequate in securing these communities and re-establishing rule of law. Community policing should have been integrated into the larger counterinsurgency effort, but instead, vigilante groups have been created to fight alongside the military. The next administration should make police reform a priority within the larger defense and security sector review. Attention also needs to be given to strengthening the police and improving coordination between the police and the military.

Ogbozor: Food insecurity should be a priority, as the Middle Belt (Nigeria’s food basket) continues to be hit by farmer-herder violence. The lack of trust in the government should be addressed as part of the security sector reform process. This should also include a commitment by senior leaders to rededicate themselves to governing responsibly and ethically. During the run-up to the elections many Nigerians were alarmed by a series of controversial executive branch actions. One was the removal of the chief justice and his replacement by an Islamic law scholar. Another was the appointment of a close relative of the president to head the electoral commission. Yet another was a directive that required results from the polling stations to be transported to collection centers by road, rather than through technology as demanded by the House of Representatives. Such actions erode public confidence in government and are a source of instability. The next government can strengthen stability by respecting checks and balances on the executive branch.

What are some priority changes the next administration should take to more effectively deal with the country’s security challenges?

Wapmuk: A comprehensive review and restructuring of the entire security architecture is warranted. A far-reaching and inclusive security review should help address the persistent problems of mismanagement, politicization, and impunity. It will also create an enabling environment for military personnel to be well-equipped and motivated and for different government departments to develop more effective interagency collaboration. The farmer-herder conflicts will require broader and more innovative solutions. It is no longer fashionable to move cattle from one part of the country to another in search of pasture. Ranching has long emerged as a practice in other parts of the world, where cattle owners make more money. Farmers can produce feed for the Fulani herders to buy at reasonable prices and also purchase meat and dairy products so as to create economic interdependencies. The next government will also have to work more intensively with neighboring countries to address cross-border threats.

Onubogu: The next government will face the immediate challenge of ensuring peace in the governor and state assembly elections that will be held after the presidential polls. These are going to be heated elections, as local governments in Nigeria have tremendous power and access to resources. The government will need to quickly organize itself to replicate the peace pacts that have been signed at the national level to ensure that they are adhered to by all aspiring candidates. The international community should also be proactive in ensuring that the same messages they sent to the presidential candidates also reach the governors.

Nearly every acute security challenge in Nigeria has been exacerbated by urban conditions.

Duerksen: Addressing and prioritizing urbanization as a component of national security is a change in approach the next administration should consider. Currently there is neither a federal agency nor ministry that directly oversees urban development. Empowering a new or existing arm of government to approach urbanization as a security challenge could help Nigeria identify and address specific aspects of urbanization tied to both violent and structural security challenges. This would allow for better mobilization of resources to tackle urbanization challenges in proportion to the significant and rising level of threat that they constitute. There is little to no coordination between Nigerian cities in tackling shared security threats and in tracking criminal and terrorist networks operating between them. A centralized agency could enable a more sophisticated approach to hampering corruption (money laundering via urban real estate) and terrorist groups’ finances, recruitment, and communication strategies.

Additional Resources

- Jibrin Ibrahim and Saleh Bala, “Civilian-Led Governance and Security in Nigeria after Boko Haram,” Special Report, United States Institute of Peace, December 2018.

- Aly Verjee, Chris Kwaja, and Oge Onubogu, “Nigeria’s 2019 Elections: Change, Continuity, and the Risks to Peace,” Special Report No. 429, United States Institute of Peace, September 17, 2018.

- Oluwakemi Okenyodo, “Governance, Accountability, and Security in Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief, No. 31, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 2016.

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies Research Paper No. 6, July 2014.

- Michael Olufemi Sodipo, “Mitigating Radicalism in Northern Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 26, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 31, 2013.

- Chris Kwaja, “Nigeria’s Pernicious Drivers of Ethno-Religious Conflict,” Africa Security Brief No. 14, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2011.

More on: Countering Violent Extremism Democratization Identity Conflict Police Sector Reform Security Sector Governance Nigeria