- Part 1: Identity

- Part 2: Faultlines

- Part 3: Extremism

- Part 4: Boko Haram

- Part 5: Strategies for combating extremism

- Part 6: Military professionalism

- Part 7: Maritime security

- Part 8: Governance

The date was June 11, 2009. Nearly 20 unarmed Boko Haram motorcyclists were fatally shot by police for refusing to wear safety helmets. The episode was the culmination in a series of confrontations with police that led the authorities to view the incident as a direct challenge. Boko Haram at the time, however, primarily operated as a religious cult and had not fully committed to violence. These members had been on their way to a funeral of one of their colleagues who had died in a car accident. The shooting triggered a five-day uprising by sympathizers that spread to four northern states leading to more than 800 fatalities and the capture and mysterious death in police custody of Boko Haram’s founder, Mohammed Yusuf. Members were tracked and killed, had their properties confiscated and many were incarcerated. In disarray but vengeful, Boko Haram went underground. Yusuf’s successor, Abubaker Shekau, adopted a far more militant approach. He appealed to his followers to regroup and “redeem their honor.” About a year and a half later Boko Haram re-emerged as one of Africa’s most brutal terrorist organizations. This sequence, a key turning point in Boko Haram’s evolution, illustrates the limitations of overwhelmingly kinetic approaches to combating extremism.

The date was June 11, 2009. Nearly 20 unarmed Boko Haram motorcyclists were fatally shot by police for refusing to wear safety helmets. The episode was the culmination in a series of confrontations with police that led the authorities to view the incident as a direct challenge. Boko Haram at the time, however, primarily operated as a religious cult and had not fully committed to violence. These members had been on their way to a funeral of one of their colleagues who had died in a car accident. The shooting triggered a five-day uprising by sympathizers that spread to four northern states leading to more than 800 fatalities and the capture and mysterious death in police custody of Boko Haram’s founder, Mohammed Yusuf. Members were tracked and killed, had their properties confiscated and many were incarcerated. In disarray but vengeful, Boko Haram went underground. Yusuf’s successor, Abubaker Shekau, adopted a far more militant approach. He appealed to his followers to regroup and “redeem their honor.” About a year and a half later Boko Haram re-emerged as one of Africa’s most brutal terrorist organizations. This sequence, a key turning point in Boko Haram’s evolution, illustrates the limitations of overwhelmingly kinetic approaches to combating extremism.

A Problematic Military Response

Starting in 2012, Boko Haram began staging coordinated attacks on military and civilian targets across northern Nigeria including near-weekly suicide bombings in major population centers. In response, in May 2013 President Goodluck Jonathan declared a state of emergency in three northeast states—Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa states. The national government, in turn, assembled a joint task force (JTF) of military, police and customs officers to battle Boko Haram. The government simultaneously committed to an upswing in defense spending from $800 million to $5.4 billion between 2009 and 2014.

The JTF mission, however, has been criticized for indiscriminate arrests, torture, and extra-judicial killings of suspected Boko Haram sympathizers and members. In one operation in Baga, in the northeastern state of Borno, JTF members reportedly destroyed more than 2,000 buildings, apparently in retaliation for the killing of a soldier by Boko Haram.

This heavy-handed approach has, at best, been ineffective. Some have argued that it has been counterproductive. The frequency and intensity of Boko Haram attacks grew from 2013 to 2014. Meanwhile, the government’s approach has alienated civilians and reduced their willingness to provide valuable intelligence about Boko Haram. “The government cannot hope to defeat Boko Haram if it does not change its counterinsurgency strategy,” says Hussein Solomon. Winning the trust and support of the population is indispensable.

This lack of trust is further perpetuated by pre-existing faultlines, in particular between the relatively underdeveloped and predominantly Muslim North, where the insurgency is based, and the more affluent and largely Christian South. These dichotomies fuel perceptions among many northerners that they are being systematically marginalized by the secular authorities. Add to this the government’s inability to protect civilians and the resulting proliferation of vigilante groups, and the seeds for new iterations of instability may well be being sown.

Governance and the Rule of Law

Addressing social and economic grievances that terrorist organizations exploit to win recruits is a crucial element in a larger strategy to combat extremism. Endemic corruption is also to blame. Complaints about corruption in the judicial sector are rife, including the practice of “buying judgments.” With few trained forensic staff, police tend to rely on confessions, which form 60 percent of all prosecutions.

Human rights reports suggest, however, that some of these confessions are extracted under torture. The reintroduction of Sharia Law in twelve northern states in 1999 was expected to be a means to counter the corruption of the secular justice system, strengthen the local population’s sense of belonging to a national Nigerian fabric, and augment stability. However, this too has fallen short of expectations because Sharia courts are perceived by many to be as corrupt as their secular counterparts. Rejectionist and extremist ideologies are thriving in the wake of these ineffective governance initiatives and the perceived lack of justice. As a result, Boko Haram has a wide pool from which to win recruits.

Building Bridges

In Nigeria, traditional institutions exist in parallel with federal, state and local governments and have historically played an important role in fostering nonviolent means of conflict resolution. Several have been involved in efforts to counter youth radicalization in northern Nigeria. However, many youth seem to be shifting their loyalties away from traditional and religious institutions to Boko Haram and other extremist organizations.

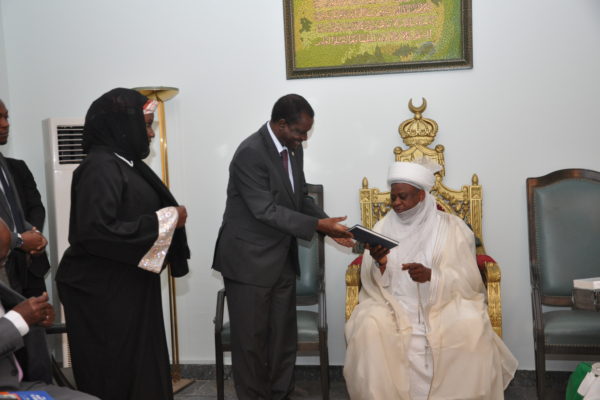

The revered Sultan of Sokoto and his counterpart, the Shehu of Borno, for instance, have publicly denounced Boko Haram and have been involved in high-level efforts to promote cooperation between Muslim communities (especially youth) and the government. They have also participated in an ongoing interfaith dialogue with Christian leaders. Yet these have not succeeded in stemming terrorist recruitment. At issue are two factors. First, many northerners question the credibility of their traditional and religious leaders who for the most part are perceived to be part and parcel of the corrupt political establishment. Second, despite Nigeria’s tradition of religious moderation, radical voices appear to be more successful in reaching youth than moderate ones.

The revered Sultan of Sokoto and his counterpart, the Shehu of Borno, for instance, have publicly denounced Boko Haram and have been involved in high-level efforts to promote cooperation between Muslim communities (especially youth) and the government. They have also participated in an ongoing interfaith dialogue with Christian leaders. Yet these have not succeeded in stemming terrorist recruitment. At issue are two factors. First, many northerners question the credibility of their traditional and religious leaders who for the most part are perceived to be part and parcel of the corrupt political establishment. Second, despite Nigeria’s tradition of religious moderation, radical voices appear to be more successful in reaching youth than moderate ones.

Boko Haram, meanwhile, has made a point of violently targeting moderate imams so as to dissuade any moves toward reconciliation and compromise as this would work against the group’s polarizing agenda. These tensions have led some to suggest that the real tension in northern Nigeria is not necessarily between aggrieved Muslims and the secular federal government but a struggle within the Muslim community over whether and how to embrace moderation and how to interpret Islamic jurisprudence. Scholar John Paden suggests that the solution to this problem lies in working more closely with moderate voices to push for national and local reforms, empower traditional leaders and promote interfaith dialogue.

In short, the rapid expansion of Boko Haram’s influence in northern Nigeria is as much a reflection of ineffective and weak government presence at the federal, state, and local levels as of the dominance of Boko Haram militarily. “You cannot fix this insurgency without fixing the state,” warns Hussein Solomon. Experience thus far suggests that combating extremist ideology and stabilizing northern Nigeria will require a multi-sectoral effort involving a calibrated military strategy, active governance initiatives at the local level, and building bridges with trusted, moderate community leaders.

In short, the rapid expansion of Boko Haram’s influence in northern Nigeria is as much a reflection of ineffective and weak government presence at the federal, state, and local levels as of the dominance of Boko Haram militarily. “You cannot fix this insurgency without fixing the state,” warns Hussein Solomon. Experience thus far suggests that combating extremist ideology and stabilizing northern Nigeria will require a multi-sectoral effort involving a calibrated military strategy, active governance initiatives at the local level, and building bridges with trusted, moderate community leaders.

The next article in the series discusses military professionalism.

Further Reading

- Christopher Harmon, Illustrations of Discrete Uses of Force in Counterterrorism, Orbis, Volume 54, Issue 3, 2010.

- James Q. Roberts, “Building a National Counterterrorism Capability: A Primer for Operators and Policymakers Alike,” Consortium of Defense Academies and Security Studies Institutes, International Security Network (ISN), 2011.

- Samson Eyituoyo Liolio, “Rethinking Counterinsurgency: A Case Study of Boko Haram in Nigeria,” European Peace University, February 2013.

- Kieran E. Uchehara, “Peace Initiatives between Boko Haram and the Nigerian Government,” Istanbul, Turkey: International Journal of Business and Social Sciences, Vol 5, No 6, May 2014.

- Zachary Devlin-Foltz, “Africa’s Fragile States: Empowering Extremists, Exporting Terrorism,” Africa Security Brief No. 6, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 2010.

- Ben Connable and Martin C. Libicki, “How Insurgencies End”, Rand Corporation, 2010.

Africa Center Experts

- Dr. Benjamin Nickels, Associate Professor and Academic Chair, Transnational Threats and Counterterrorism

- Dr. Raymond Gilpin, Academic Dean

- Dr. Joseph Siegle, Director of Research

- Dan Hampton, Professor of Practice, Security Studies

[Photos: Voice of America, Voice of America, ECOWAS]

More on: Boko Haram Extremism Nigeria