- Part 1: Identity

- Part 2: Nigeria’s Faultlines

- Part 3: Extremism

- Part 4: Boko Haram

- Part 5: Strategies for combating extremism

- Part 6: Military professionalism

- Part 7: Maritime security

- Part 8: Governance

Nigeria’s most talked about faultline is the economic and social imbalance between the relatively underdeveloped, historically marginalized and mainly Muslim north, and the wealthier, more industrialized and predominantly Christian south. Nigeria’s northern states account for roughly 66 percent of the country’s poor – a disparity that is seen to be growing worse. At the local level this faultline is most exposed in the country’s “Middle Belt,” particularly the states of Plateau and Kaduna where Hausa-Fulani Muslims and Yoruba-Igbo Christians are evenly divided. The region has experienced internecine violence resulting in the loss of at least 7,000 lives in interreligious violence since 2001.

Other faultlines exist outside this larger narrative. Nigerian activist Tolu Ogunlesi explains that in the predominantly Christian southeast “lingering resentment among many Protestants about the perceived dominance of Roman Catholics are widespread. Similarly, in the northeast, violence between Sufi, Sunni and Shiite orders and societies occurs with frequency. Underlying these sectarian conflicts are deep socioeconomic inequalities. The conflict in the Niger Delta, located in the far south of the country, explains some of these complexities. The largest militant group there, the Movement for the Liberation of the Niger Delta, or MEND, claims that it is fighting to ensure that oil proceeds from the region are returned to the area’s residents and to secure reparations from the federal government for environmental pollution caused by this industry. While violence in the Niger Delta has subsided in recent years, MEND has indicated that it would resume its campaign should Muhammadu Buhari, the winner of Nigeria’s presidential election and a northerner, come to power. Nigeria’s multiple faultlines, in short, defy simplistic explanations.

How Are Nigeria’s Faultlines Exploited in the Political Process?

While the “North-South, Muslim-Christian” dichotomies mask a much more nuanced conflict picture, they are by far the most invoked by the country’s top politicians giving them more resonance at the national level according to Africa scholar John Campbell. These differences are used by political leaders in the fierce competition for public office and control over resources that can support the extensive patronage networks that have dominated Nigerian politics. It is believed that Boko Haram was initially supported and protected by local politicians to gain greater leverage in this political maneuvering but the insurgency eventually turned on the politicians and grew into a terrorist movement that no one appears capable of controlling.

The declaration of a State of Emergency in the northeastern states of Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa by President Goodluck Jonathan in December 2013 led to the deployment of thousands of federal troops in the region. In the process of combatting Boko Haram, these troops were widely alleged to have committed human rights violations against innocent civilian populations in the north. As a result, many northerners feel they are under occupation by a foreign entity.

An examination of these fault lines illustrates that ethnicity and religion are not the driving force behind Nigeria’s conflicts but rather narratives politicized to mobilize support for economic, regional, and political goals. Clement Mweyang Aapengnuo observes, “People do not kill each other because of ethnic differences; they kill each other when these differences are promoted as the barrier to advancement and opportunity.”

Failure of ethical leadership is largely to blame for this state of affairs according to celebrated Nigerian writer and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka. In the absence of such leadership, dominant and harmful narratives have become embedded in the political process. Accordingly, for many northern politicians control of the presidency is the only viable means of “catching up” with the more developed and affluent south. Many southern politicians, for their part, point to the fact that most Nigerian military rulers since independence have been northern Muslims. The North must accordingly “be kept in check.” These two dominant narratives are relevant to understanding the faultline dynamics that heighten the risk of conflict in Nigeria.

What Attempts Have Been Made to Heal These Divides?

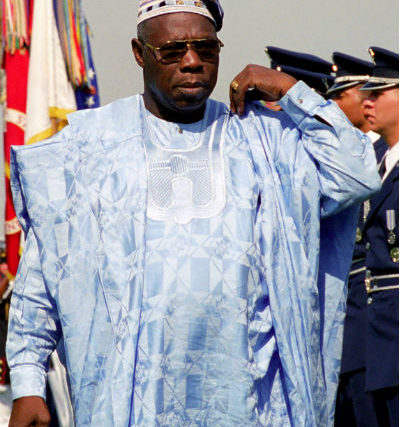

Olusegun Obasanjo

With the restoration of civilian rule and Nigeria’s turn toward democracy in 1999, northern and southern political elites of the People’s Democratic Party attempted to resolve their zero sum approaches to politics through political power sharing. They reached a “gentleman’s agreement” to rotate the presidency between the North and South. Under the arrangement Olusegun Obasanjo, a southerner, ruled from 1999 to 2007. In keeping with the arrangement Umaru Musa Yar’Adua, a northerner, took over from Obasanjo but died in office in 2010. Goodluck Jonathan, then Vice President and a Christian from the South, assumed leadership and secured his party’s nomination to contest the 2011 presidential elections which he won. Embittered, many northern elites accused him of breaking the accord, in particular marginalizing their region which they say has held political power for only three of the last 15 years thanks to “manipulation by southerners.” These grievances might ease given Buhari’s victory but resolving the long-running suspicion between northern and southern populations will require the concerted attention of political leaders.

Besides political power-sharing Nigeria has experimented with institutional and legal measures to alleviate concerns by minorities about their exclusion from the political process and complaints about lack of service delivery on the basis of ethnicity and religion. However, even these have been met with mixed success. A case in point is the Federal Character Commission (FCC), a statutory body established in 1996 to provide affirmative action and promote equity in public appointments. The commission authorized local officials to issue so called “indigene certificates,” a practice recognized by Nigeria’s constitution. Under this system, residents who are indigenous to a particular area enjoy rights denied to those who are not.

Besides political power-sharing Nigeria has experimented with institutional and legal measures to alleviate concerns by minorities about their exclusion from the political process and complaints about lack of service delivery on the basis of ethnicity and religion. However, even these have been met with mixed success. A case in point is the Federal Character Commission (FCC), a statutory body established in 1996 to provide affirmative action and promote equity in public appointments. The commission authorized local officials to issue so called “indigene certificates,” a practice recognized by Nigeria’s constitution. Under this system, residents who are indigenous to a particular area enjoy rights denied to those who are not.

These rights include the ability to own land and access to education and government employment. Possession of the “indigene” certificate is therefore a license to socioeconomic advancement and therefore highly sought after and therefore prone to abuse. Since allocation of these certificates is at the discretion of local authorities, households may live in a jurisdiction for generations and still be deemed “a settler.” Instead, local politicians have a strong incentive to use these highly coveted certificates as a tool to consolidate ethnic and religious majorities.

Consequently minority communities across Nigeria’s 36 states feel increasingly disenfranchised and aggrieved. At the heart of the issue, according to Kwaja, is that Nigeria’s systems of political power sharing and resource allocation further entrench the country’s multiple faultlines. These will only be addressed with fundamental reforms.

The next issue discusses how these faultlines have contributed to extremism and insurgency in Nigeria.

Further Reading

- John Campbell, “Why a Terrifying Religious Conflict is Raging in Nigeria,” The Atlantic, July 10, 2013

- Tolu Ogunlesi, “Nigeria’s Internal Struggles,” New York Times, March 23, 2015.

- Chris Kwaja, “Nigeria’s Pernicious Drivers of Ethno-Religious Conflict,” Africa Security Brief No. 14 (Washington, DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2011).

- Jideofor Adibe, “The 2014 Elections in Nigeria: Issues and Challenges,” (Washington DC: Brookings Institution, March 2015).

- Clement Mweyang Aapengnuo, “Misinterpreting Ethnic Conflicts in Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 4 (Washington, DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 2010).

Africa Center Experts

- Dorina Bekoe, Professor for Conflict Prevention, Mitigation, and Resolution

- Raymond Gilpin, Academic Dean

[Photo credit: Temi Kogbe]

More on: Boko Haram Nigeria