Part 1: Identity

- Part 1: Identity

- Part 2: Faultlines

- Part 3: Extremism

- Part 4: Boko Haram

- Part 5: Strategies for combating extremism

- Part 6: Military professionalism

- Part 7: Maritime security

- Part 8: Governance

After a hard-fought and competitive election, Muhammadu Buhari became Nigeria’s 4th democratically elected president. Observers from around the world commended Nigeria for the smooth transition between rival political parties. Nigerians, neighboring countries, and international actors alike are now expectantly watching to see how Nigeria manages the many challenges facing Africa’s most populous country and largest economy.

Key among these is security. Nigeria has increasingly been in the global spotlight in recent years because of the rise in attacks by Boko Haram, the violent extremist group. This has resulted in the deaths of over 10,000 people since 2014. Less recognized is that Boko Haram is but one of a series of interlocking security and governance challenges that the new government in Nigeria will face. This compilation reviews some of the most pressing of these fundamental challenges and the leadership that will be required to address them.

Is There Any Such Thing as a “Nigerian Nation” and What Does it Mean to be Nigerian?

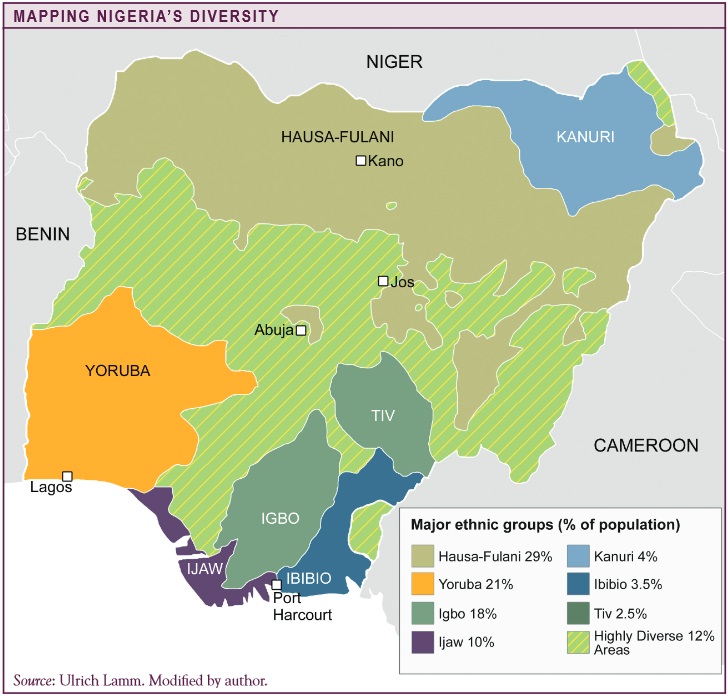

Since Nigeria’s independence in 1960, strong ethno-religious identities have prevented a truly pan-Nigerian identity from developing. Politically, Nigeria is a federation of 36 states. Ethnically, it is home to 250 different groups, though the 3 largest ethnicities—Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba, and Igbo—account for about 68 percent of the population. Religiously, Nigeria is divided along its so-called “Middle Belt” between the mostly Muslim north and the majority Christian south. Additionally, local laws sanctioned by the national constitution further divide citizens into “indigenes” and “settlers” within each locality. Indigenes (“sons of the soil”) enjoy rights denied to settlers (even those whose families’ residence go back generations). These rights include the ability to own land and access to education, politics, and government employment.

Since Nigeria’s independence in 1960, strong ethno-religious identities have prevented a truly pan-Nigerian identity from developing. Politically, Nigeria is a federation of 36 states. Ethnically, it is home to 250 different groups, though the 3 largest ethnicities—Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba, and Igbo—account for about 68 percent of the population. Religiously, Nigeria is divided along its so-called “Middle Belt” between the mostly Muslim north and the majority Christian south. Additionally, local laws sanctioned by the national constitution further divide citizens into “indigenes” and “settlers” within each locality. Indigenes (“sons of the soil”) enjoy rights denied to settlers (even those whose families’ residence go back generations). These rights include the ability to own land and access to education, politics, and government employment.

How people choose to identify themselves is not necessarily problematic scholar Francis Deng has observed, but to manage a pluralistic identity, a government should create a national framework with which all can identify without any distinction based on ethnicity, tribe, or religion. With most Nigerians deriving their sense of belonging from an ethno-religious perspective or from an assigned affiliation as an indigene or settler, Nigerians’ lack of common citizenship reinforces polarities in ethnic, religious, regional, and legal status. And without a shared identity or meaningful engagement in one another’s lives, neighbors find it easier to respond to perceived differences to devalue one another. In Nigeria, identity conflicts mask deeper systemic issues at the center of which is the relationship between political power and access to economic resources and opportunities. Ethnic thinking and mobilization emerge from this struggle for power, wealth, and resources, notes Clement Mweyang Aapengnuo, not from an intrinsic hatred.

Why Have Nigeria’s Leaders Not Succeeded in Building a Truly Nigerian Nation?

Since 1979, Nigeria has been governed through a power-sharing arrangement mandated by its constitution which requires equal representation in key political and bureaucratic positions among its diverse communities “to reflect the federal character of Nigeria and the need to promote national unity.” Over time, however, this has transformed into a patronage system of governance—a pacifying system of distribution and allocation. Rather than promoting a sense of belonging and equality, this political patronage, often based on ethno-religious factors, has contributed to marginalization and corruption, which has created integrity and legitimacy problems for the government.

Chris Kwaja explains that political patronage, long entrenched in Nigerian politics, “provides an institutionalized incentive for political opportunists to build power on the basis of exclusion.” Many of the practices associated with it, such as the fraudulent issuance of indigene certificates by politicians “undermine the democratic form of government that Nigeria aspires to uphold and undercut the very notion of what it means to be Nigerian.” This explains why, for instance, religious leaders command more loyalty than the central government in Abuja.

Reflecting on the challenges the government faces in the wake of security crises in the northeast, along the Middle Belt, in the Niger Delta region, and in the Gulf of Guinea, longtime Nigeria scholar, John Paden, points to the government’s inability to provide an effective system of equitable distribution, manage ethno-religious relations, uphold accountable governance, and exercise the responsibility to protect its population. Deng cautions that peace and stability will elude a pluralistic state until it develops norms and means for managing diversity within a framework of unity. Nigeria’s viability as a nation-state depends upon this. This will entail measures that directly mitigate violence as well as realize constitutional reform to address perceptions of marginalization. Unfortunately, advancing such a vision has not been part of the electoral discourse.

The next issue in this series examines Nigeria’s multiple faultlines.

Further Reading

- Chris Kwaja, “Nigeria’s Pernicious Drivers of Ethno-Religious Conflict,” Africa Security Brief No. 14 (July 2011).

- Francis M. Deng, “Ethnicity: An African Predicament,” The Brookings Review 15, no. 3 (Summer, 1997), 28-31.

- Michael Olufemi Sodipo, “Mitigating Radicalism in Northern Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 26 (August 2013).

- Clement Mweyang Aapengnuo, “Misinterpreting Ethnic Conflicts in Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 4 (April 2010).

- Togu Ogunlesi, “Nigeria’s Internal Struggles,” The New York Times, March 23, 2015.

Videos

- Hussein Solomon, “Governance Reforms May Be More Effective Than Military in Countering Boko Haram,” presentation at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University, Washington, D.C., March 28, 2013.

- John Paden, panel presentation at “Understanding and Mitigating the Drivers of Islamist Extremism in Northern Nigeria” roundtable at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University, Washington, D.C., December 13, 2013.

Africa Center Experts

- Dorina Bekoe, Professor for Conflict Prevention, Mitigation, and Resolution

- Raymond Gilpin, Academic Dean

- Joseph Siegle, Director of Research

More on: Boko Haram Nigeria