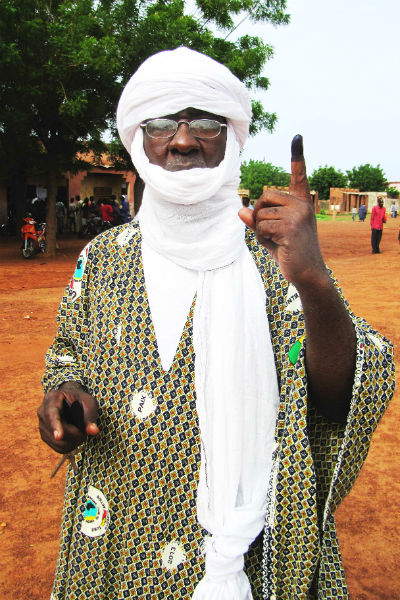

A Malian woman votes in the 2013 election. Photo: MINUSMA/Marco Dormino.

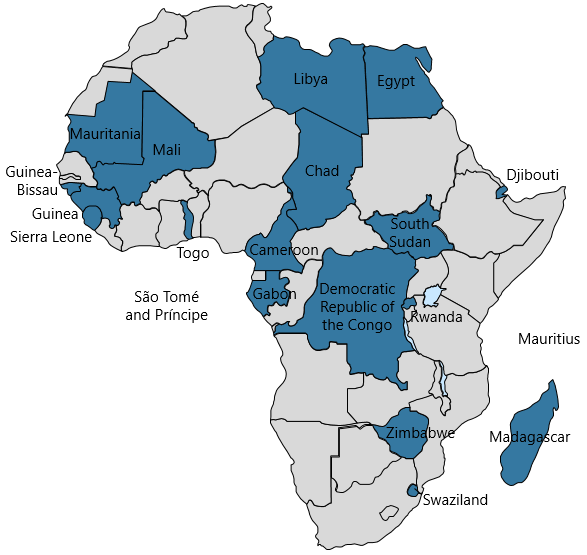

In 2018, 20 countries in Africa will hold presidential and parliamentary elections. Past experience indicates that 20 percent of African elections have experienced violence resulting in fatalities. To better understand the prospects for electoral violence in 2018, this analysis reviews countries facing unique challenges to holding peaceful elections.

Yet, violence is not a foregone conclusion. International and domestic stakeholders can take important steps ahead of elections to reduce the potential for violence. As nearly 95 percent of all electoral violence takes place before elections, early warning requires early action to leverage political will and financial capital to forestall violence.

National Elections in Africa in 2018

South Sudan

South Sudan, in the grip of a civil war since December 2013, has delayed indefinitely its initial plans to hold elections July 9, 2018—which in turn were originally scheduled for 2015. The war, which has defied resolution efforts by regional and international bodies, now stands as one of Africa’s greatest humanitarian tragedies. More than one-third of South Sudan’s 12 million people have fled their homes: the war has driven more than 2.4 million to seek refuge in neighboring countries, while nearly 2 million are internally displaced.

Elections taking place in the presence of armed opposition groups invites the violent contestation of results, entrenches disenfranchisement, and undermines the legitimacy of the government even further. Angola’s attempt to hold elections in 1992 without disarming insurgents of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola or the government’s Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola ended in a return to war within four months. Similarly, violence broke out after the 2006 election in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), when armed supporters of Jean-Pierre Bemba protested his loss.

Holding elections in South Sudan in the absence of viable peace process and humanitarian program will in all likelihood only deepen the conflict.

Libya

Seven years after the Arab Spring resulted in the death of President Muammar Ghaddafi, Libya remains an unstable, violent, politically and regionally divided country, as well as a haven for extremist groups. Presidential and parliamentary elections have been scheduled for the end of 2018. However, much of the institutional infrastructure and political stability needed for an effective electoral process does not exist. The 2015 Libyan Political Agreement (LPA), a central part of the UN-led peace process, calls for pertinent constitutional and electoral reforms that have not yet been implemented. Without the implementation of the LPA, Libya lacks an agreed upon framework to harness political competition.

Holding elections cannot substitute for an inclusive peace process, where spoilers are disarmed or marginalized, rule of law is established, a path to reconciliation exists, and citizens can exercise their rights freely.

Egypt

Egyptian president Abdel Fattah Al Sisi won his second term in office in March. Al Sisi seized power in 2013, when he toppled the government of Mohammed Morsi. Upon assuming power, Al Sisi violently repressed the Muslim Brotherhood—Morsi’s party—as well as journalists, civil society organizations, human rights defenders, and demonstrators.

While analysts saw his re-election in such a controlled process as a foregone conclusion, the pre-election period was anything but smooth. The Al Sisi government has violently harassed and intimidated any opposition. Candidates that dared to oppose him have been arrested or discouraged from continuing, as have others who have voiced dissent. A consortium of political parties called for a boycott in protest of the lack of fairness in the electoral process. The government, in turn, has threatened those who do so.

More meaningful leverage is needed to support Egypt’s democratic transition.

Mali

A man shows off his inked finger after voting in Mali’s relatively peaceful 2013 election.

Mali—which has faced an insurgency in its northern regions since 2012—plans to hold presidential elections on July 29, 2018, and parliamentary elections in November or December. While the 2013 elections took place with relatively little election-related violence, the security landscape since then has evolved. In the long-delayed communal elections of 2016, armed groups in the north prevented elections from taking place in some constituencies and attacked electoral officials and offices in others. Indeed, the threat of violence has caused the postponement of regional and local elections, which were originally due to take place in December 2017, until April 2018.

Despite the 2015 Algiers Accord and the deployment of the 13,000-strong UN peacekeeping mission (MINUSMA), the ongoing conflict in the north persists. MINUSMA has earned the unenviable title as the deadliest environment for peacekeepers. Moreover, the government does not have a strong presence in the north. This presents logistical and organizational difficulties to preparing for the elections. In addition to the faltering Algiers Accord, the G5 Sahel Joint Force (comprising Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger) has yet to prove that it will bring stability. Preventing electoral violence in Mali will require a more robust peace and disarmament process to reduce both the incentive and the capacity to attack civilians and government representatives.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is scheduled to hold presidential elections in December 2018, polls postponed from December 2016. The government’s delaying tactics—such as its proposal of a new census prior to the elections and the creation of additional provinces—precluded their timely organization. After the 2016 delay, several violent protests ensued, as many suspected that the sitting president, Joseph Kabila, simply sought to exceed his mandate. Mediation led by the Catholic Church resulted in the Saint Sylvester agreement between the opposition and the government, which called for elections in December 2017. However, this deadline also passed, drawing fresh protests led by the Catholic Church in Kinshasa and elsewhere. The government violently crushed those protests, resulting in several deaths.

The latest electoral calendar has also been met with deep skepticism. With the Saint Sylvester agreement essentially abandoned, the DRC must confront the challenge of taking credible steps toward the organization of elections. Unless the government takes concrete and irreversible steps or faces sanctions by the international and regional communities for failing to do so, the coming year portends more protests and violence in Congo.

Cameroon

Paul Biya, in power since 1982 and second only to Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang Nguema as the longest serving African president, will likely seek re-election in October. Barring a unified and strengthened opposition, he will probably win. However, the campaign or the postelection period could be turbulent. Unlike past electoral periods, Cameroon faces domestic unrest that could mar the next several months with violence.

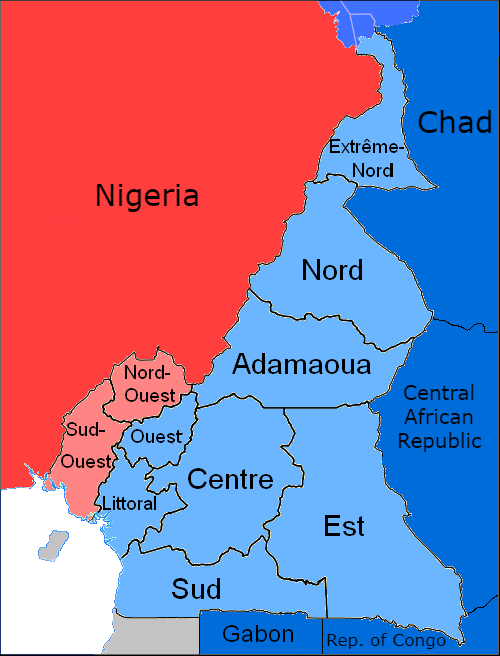

Language map of Cameroon. French-speaking areas are in blue; English-speaking areas are in red. Adapted from an image by Aaker.

Since October 2016, Cameroon’s Anglophone regions in the west have repeatedly demonstrated to voice their sense of political and economic marginalization and resentment of dominance by the Francophone-majority government. While the protests at first began as a call for a return to federalism, some have called increasingly for secession—naming the new independent territory the Federal Republic of Ambazonia and appointing an interim government. Violence has steadily increased in the Anglophone regions: approximately 60 civilians, 16 security officers, and an unknown number of militant fighters have lost their lives. Demonstrations by Anglophones have been met harshly and several dozen armed groups in the southwest have formed to counter government attacks. Most tellingly, Biya has not offered to resolve these long-standing grievances through dialogue, opting to continue to forcefully suppress dissent. Some within the government believe that only force will quell the unrest ahead of the elections.

Without the prospects of dialogue with leaders in the Anglophone region, violence will likely increase. In particular, some insurgent leaders may use violence as a means to discredit the president, Francophone candidates, or Anglophone political actors seen as supportive of the current regime. By the same logic, the government could use violence to discredit aggrieved communities in the Anglophone region. In short, organizing and administering credible elections will prove difficult, which in the end could impinge on the legitimacy of elected officials, further worsening the political and security crisis in the region.

Togo

In July 2018, Togo will hold legislative elections in the wake of nearly a year of sustained public protests and an increasingly unified political opposition calling for an end to the 50-year rule by the Gnassingbé family and the Rassemblement du Peuple Togolais/Union pour la République (RPT/UNIR). These latest demonstrations distinguish themselves from past movements by the degree of unity shown by the opposition. Moreover, the party leading the protests, the Pan-African National Party, does not yet have representation in the assembly and hails from northern Togo, the ruling party’s stronghold. Protests have spread far beyond Lomé, the capital, to include Bafilo, Mango, and Sokodo, in the north.

President Faure Gnassingbé and the opposition seem at an impasse. Gnassingbé promises to engage in a national dialogue in a bid to launch a referendum on term limits and a two-round poll. However, the opposition discounts the utility of a national dialogue—citing many failed attempts in the past. In addition to demanding for Gnassingbé to resign, they also call for a return to the 1992 constitution, revisions to the electoral framework, and diaspora voting rights.

The forthcoming legislative elections may portend more political violence, as the opposition—now a union of 14 different parties—fights to improve its standing in the National Assembly. Currently, the ruling RPT/UNIR party holds 62 of the 91 seats in the National Assembly. The governments of Ghana and Guinea have announced that a dialogue between the Togolese parties would begin in February in Lom. In view of the upcoming elections, the mediation should focus on developing an inclusive process, a transparent electoral commission, and implementation of measures to allow the opposition to campaign safely.

Zimbabwe

At the time of Robert Mugabe’s resignation in November 2017, he had been the one of the longest serving presidents in Africa, having come to power in 1980. His resignation signified the culmination of a widening rift in the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) over Mugabe’s successor, pitting supporters of his wife, Grace Mugabe, against those of Emmerson Mnangagwa, a leader from Zimbabwe’s fight for independence.

The mechanisms that Zimbabwe’s government puts in place to respond to these challenges will largely indicate whether the immediate post-Mugabe era reflects a true transition or just old wine in new bottles.

Zimbabwe is due to hold general elections July 30, with Mnangagwa as the flagbearer for ZANU-PF. The post-Mugabe period faces challenges to restore credibility in the economy, judiciary, and security sectors. Mnangagwa has promised that the 2018 elections will be free, fair, and credible. In the past, Zimbabwe’s elections have been among the continent’s most violent, as the ruling party resorted to desperate means to retain power. Between the first and second rounds of the presidential election in 2008, more than 200 people were killed, prompting the opposition to withdraw from the contest.

Credibility will be central to Zimbabwe’s elections. In the past, elections have not been transparent or safe, nor have they reflected the will of the people. The mechanisms that Zimbabwe’s government puts in place to respond to these challenges will largely indicate whether the immediate post-Mugabe era reflects a true transition or just old wine in new bottles.

Madagascar

Madagascar’s presidential and parliamentary elections, scheduled for the end of 2018, raise concerns because of their potential to exclude dominant political figures and their supporters. Madagascar’s most recent political crisis stems from the 2009 military coup that replaced President Marc Ravalomanana with Andry Rajoelina. An agreement brokered by the Southern African Development Community in 2011 resulted in the election of Hery Rajaonarimampianina in 2013 in a contest that barred Ravalomanana and Rajoelina from running.

President Rajaonarimampianina will contest the 2018 elections for a second term. However, many speculate that Ravalomanana and Rajoelina will also enter the race. There are concerns that Rajaonarimampianina may prevent them from contesting, which some fear may result in protests from their supporters. Given the history of violent political confrontation in the country, excluding them could result in civic unrest. The bitter rivalry between Ravalomanana and Rajoelina has resulted in many previous violent confrontations and political turmoil.

The challenge facing the upcoming elections in Madagascar does not center on whether Ravalomanana and Rajoelina can participate, but rather how to construct a process that will mitigate violent confrontations. Purposely excluding them as candidates may well result in unrest. However, their re-emergence on the political scene is not trivial. Many died as a result of the bitter rivalry between Ravalomanana and Rajoelina. It also resulted in Madagascar’s exclusion by international donors and organizations, the results of which were severe. Interventions by regional and national leaders should focus on developing some ground rules for contestation, avenues for negotiation between the political camps, monitoring to identify and respond to issues of growing tension, and developing processes to sanction those that resort to violence.

Africa Center Experts

- Dorina Bekoe, Associate Professor of Conflict Prevention, Mitigation, and Resolution

- Joseph Siegle, Director of Research

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Term Limits for African Leaders Linked to Stability,” Infographic, February 23, 2018.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Humanitarian Costs of South Sudan Conflict Continue to Escalate,” Infographic, January 29, 2018.

- Christopher Fomunyoh, “Crisis of Governance in Cameroon,” video, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 11, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Five Issues to Watch as Zimbabwe’s Transition Unfolds,” Spotlight, November 16, 2017.

- Paul Nantulya, “A Medley of Armed Groups Play on Congo’s Crisis,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, September 25, 2017.

- Dorina Bekoe, “Storm Clouds Gather in Kenya,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 17, 2017.

- Dorina Bekoe, “Ghana’s Elections Built on Trust and Accountability,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 30, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Series: A Looming Calamity in the Democratic Republic of the Congo,” Spotlights, September 2016-January 2017.

- Joseph Siegle, “Changing the Political Calculus,” The Cipher Brief, October 11, 2016.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Africa and the Arab Spring: A New Era of Democratic Expectations,” Africa Center Special Report No. 1, November 30, 2011.

More on: Countering Violent Extremism Cameroon Democratic Republic of the Congo Libya Madagascar Mali South Sudan Togo Zimbabwe