On August 8, Kenyans went to the polls for the sixth time since the institution of multiparty elections. The lead-up to the voting, which took place in the context of a long history of electoral violence, exhibited a number of worrying signals—as well as signs of reform and progress. A peaceful outcome would depend on credible institutions—such as the judiciary to arbitrate disputes, electoral commission to manage the process, and security services to ensure the safety of citizens. Five issues are important to monitor.

1. The Elections Were the Most Competitive in Its History

Approximately 14,550 candidates competed for the 1,882 elected posts of president, governor, senator, women representatives, members of parliament, and members of county assembly. In 2013, 12,776 aspirants competed. Despite the 77 registered parties in Kenya, the political contest pitted the ruling Jubilee Party against the opposition coalition, the six-party National Super Alliance (NASA).

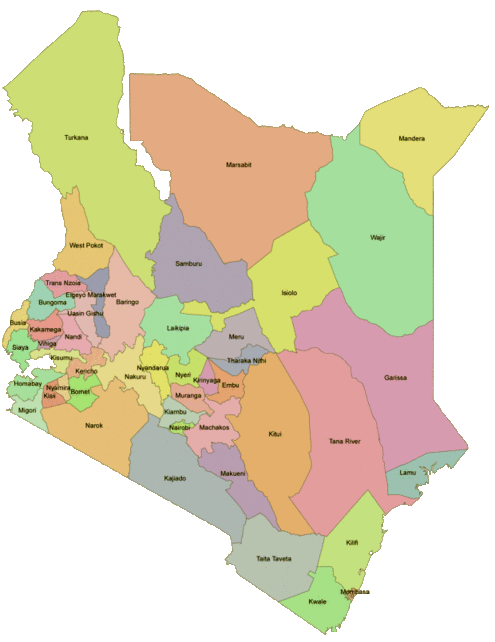

After the presidency, with its 19 candidates, the counties featured the most competitive races, with 11,000 candidates up for 1,498 elected positions—one effect of the 2013 devolution from eight provinces to 47 counties. In addition, attractive salaries and the prospect of increased grants from the central government increased competition for positions at the county levels. Combined, these factors heightened the risk that aspirants could use violence as an electoral strategy. In 2013, more than 300 Kenyans died in clashes traced to political competition at the county level. However, since the violence occurred at the local level, it did not attract much attention, and the election was declared peaceful.

Photo: Global Panorama.

2. A Perception of Impunity Hangs over the Process

The 2017 elections took place without the specter of the International Criminal Court (ICC). After the post-election violence in 2007–2008, which resulted in 1,200 deaths and 600,000 displaced, the ICC indicted six high-profile Kenyans in connection with the violence. Among the indicted were Kenya’s current president and vice president, Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto. The legal process was compromised by witnesses being harassed and intimidated. Eventually, the ICC halted the proceedings.

Kenyatta and Ruto hailed the unraveling of the ICC case as a victory. However, in the end, there was a failure to investigate, prosecute, and punish the instigators of one of the continent’s most violent elections in recent memory. In 2013, as Kenyatta and Ruto pursued the presidency, the ICC indictment served as a clear warning to all candidates, tempering language that some could consider hate speech. In 2017, no similar international watchdog exists.

Photo: Photo RNW.org.

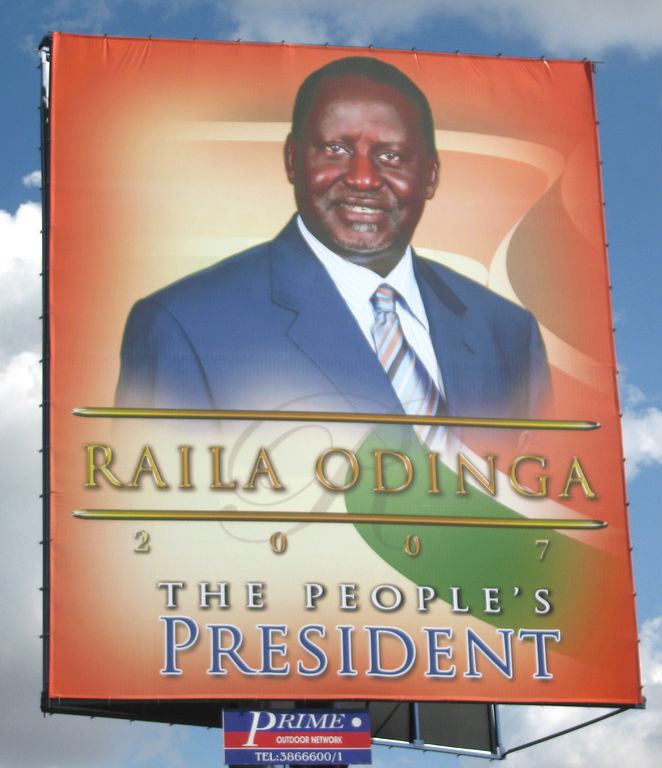

In 2007, opposition candidate Raila Odinga cited Kenya’s biased judicial system as a reason for using street protests, rather than the court system, to contest his electoral loss. Indeed, the inability of Kenya’s weak judicial system to investigate and bring to trial those responsible for the violence precipitated the referral of the designated Kenyans to the ICC. The inadequacy of the Kenyan courts also led to a concerted effort to transform the judiciary, incorporating changes into the 2010 Constitution. Since then, Kenya’s judiciary has taken a number of serious steps toward reform. These include publicly vetting judicial appointments, facilitating access by citizens to justice, increasing the training and professionalism of judiciary staff, and upgrading the information technology infrastructure. Presently, the judiciary has more than 400 judges and magistrates assigned to manage electoral disputes. However, claims by the ruling coalition that the judiciary has not acted independently raises concerns about whether the courts could serve as an avenue to redress electoral grievances.

3. NASA Has Questioned the Political Motives of the Independent Elections and Boundary Commission

NASA has accused the Independent Elections and Boundary Commission (IEBC) of organizing to steal the election by printing ballot papers through a company connected to the government. Earlier this year, NASA questioned the integrity of the voters’ register adopted by the IEBC.

In response, NASA borrowed a tactic from Ghana’s 2016 general elections. NASA successfully argued—and the Court of Appeals ruled—for vote tallies at the polling stations to serve as final results. This would make it harder to manipulate vote totals at the central level. The courts have also ruled that the opposition can conduct parallel vote tabulations (PVT). Ghana’s opposition National Patriotic Party (NPP) used PVTs to serve as a check on the official results at the polling station to document its victory. In addition, NASA has proposed using the NPP’s “Adopt a Polling Station” strategy. Under this approach, assigned party supporters will ensure that the election unfolds in a lawful and credible manner.

4. Election-related Violence Started a Year Ago

With so much focus on election day and beyond, one can overlook that most violence takes place before elections. In fact, 90–95 percent of all election-related incidents in sub-Saharan Africa have happened prior to the election. Already Kenya has experienced violence at protests against the IEBC in June 2016, during the party primaries in April and May 2017, and from politically motivated clashes between herders and conservationists in Laikipia in 2017. Police contributed to the violence, as they clashed with demonstrators during the June 2016 protests, resulting in several deaths.

5. Kenya’s Devolution from Eight Provinces to 47 Counties May Push Violence to the Subnational Level, as More Candidates Vie for Political Power

Notably, a report by the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights documented that violence during the primaries took place predominantly in western Kenya, NASA’s stronghold. On one hand, this may point to the fragility and intra-party competition of the opposition’s six-party coalition. Alternatively, it could also point to the competition generated by the devolution. In other words, while NASA may cooperate to win the presidency, the subnational positions will be hotly contested by the members of the coalition. In fact, NASA’s vice presidential candidate, Kalonzo Musyoka, a member of the Wiper party, says as much when justifying his support for only Wiper candidates in county-level elections: “NASA is going to win this election, but I don’t want to be a deputy president without governors and foot soldiers in both county and national assemblies to implement our agenda.”

There were a number of positive factors in the lead-up to the Kenyan elections. Notably, judicial decisions seemed to reflect a commitment to impartiality, and the IEBC allowed some efforts to increase transparency. However, the actions of the police, the low-intensity pre-election violence, and the competitiveness of the county-level races may worsen insecurity. National stakeholders, in partnership with regional and international actors, must focus on protecting voters and facilitating the redress of grievances through the rule of law, rather than on the streets.

Africa Center Expert

- Dorina Bekoe, Associate Professor of Conflict Prevention, Mitigation, and Resolution

Additional Resources

- Dorina Bekoe and Stephanie Burchard, “The Contradictions of Pre-election Violence: The Effects of Violence on Voter Turnout in Sub-Saharan Africa,” African Studies Review, June 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Past as Prologue in Kenya’s Elections? A Discussion with Peter Kagwanja,” video, May 23, 2017.

- Dorina Bekoe, “Africa’s Electoral Landscape: Concerning Signals, Reassuring Trends,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 2016.

- Aditi Malik, “Devolution and Electoral Violence: Has Kenya’s County System Created New Arenas for the Organization of Election-Related Conflict?” The Project on Explaining and Mitigating Electoral Violence, November 21, 2016.

- Godfrey Mukhaya Musila, Ben Sihanya, Muthomi Thiankolu, and Elisha Z. Ongoya, Handbook on Election Disputes in Kenya: Context, Legal Framework, Institutions, and Jurisprudence, October 2013.

More on: Kenya