The South African Constitutional Court in Bramfontein. (Photo: GCIS.)

Throughout his time in office, President Jacob Zuma has presented unique challenges for South Africa’s democracy. He has faced a steady stream of allegations involving patronage, money laundering, racketeering, misuse of state resources, obstruction of justice, and the abuse of power. A total of 783 charges have been levied against him in the courts. Moreover, at times, he has attempted to sidestep the institutional checks on executive power that define democracies—effectively challenging the very nature of South Africa’s political system.

Pravin Gordhan. (Photo: WEF/Sebastian Derungs.)

President Zuma’s sacking of Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan along with his deputy and 10 cabinet ministers and deputy ministers in April 2017 epitomizes this tension and prompted the largest protests in South Africa’s post-apartheid history. Prior to his dismissal, Gordhan had instituted a raft of measures to protect state-owned enterprises from executive interference and curb government spending. Crucially, this included blocking lucrative projects, such as the controversial proposal to build nuclear power plants at a cost of $148 billion—equivalent to South Africa’s entire annual budget. Consequently, observers have speculated that Gordhan was ousted because the new regulations would harm the financial interests of President Zuma’s allies.

This style of highly personalized governance is well known in Africa. In it, adherence to the rule of law is ad hoc and institutional processes are overridden by a leader’s preferences. This governance model has long been seen as contributing to corruption, inequality, and instability on the continent. However, few African countries have the same depth of institutional checks and balances as South Africa.

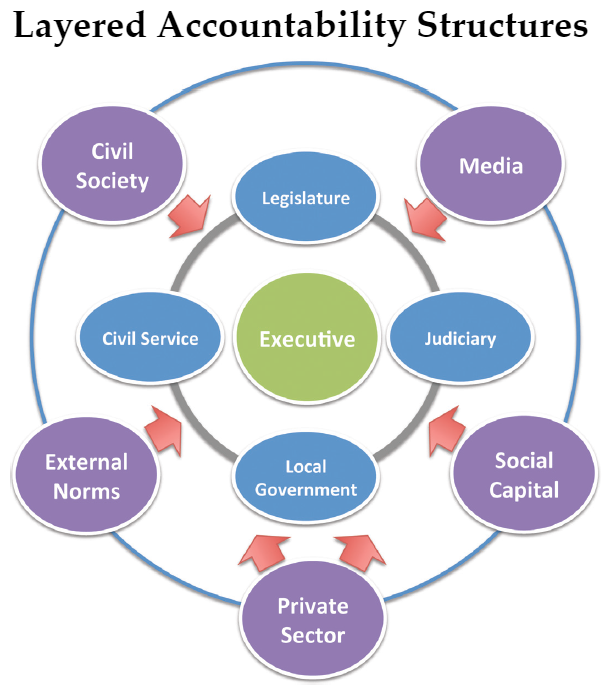

Source: Joseph Siegle, “ICT and Accountability in Areas of Limited Statehood,” in Bits and Atoms, eds. Steven Livingston and Gregor Walter-Drop (Oxford University Press, 2013).

The key question, then, is whether South Africa’s oversight institutions are strong enough to safeguard the democratic gains the country has made since apartheid ended in 1994. Or will Zuma successfully bypass those institutions and, with the ending of his term in 2019, leave a legacy of impunity that future South African political leaders will be able to further exploit? This review looks at how South Africa’s accountability structures are faring as they face this challenge.

The Public Protector

The Office of the Public Protector is the institution that has been at the forefront of efforts to enforce executive branch accountability in South Africa. It is one of nine “state institutions supporting democracy” established by the South African Constitution. Mandated to investigate and seek remedies for the abuse of state power, the office is intended to play a central role in ensuring government accountability. This unique institution has the power to initiate investigations into any public office and public official, including the president. It is also empowered to initiate investigations at the request of aggrieved individuals, organizations, and interested persons. Its decisions are legally binding.

In November 2012, then–Public Protector Thuli Madonsela began an investigation into luxury upgrades to President Zuma’s private residence at Nkandla. The investigation was completed in October the following year. However, the government sought to block the report’s release, citing national security. A provincial court denied the request and the report, Secure in Comfort, was finally released in March 2014. It found that Zuma had benefited unduly from the $23 million taxpayer-funded renovation, prompting calls for him to return some of the money.

President Jacob Zuma’s Nkandla homestead. (Photo: John A. Forbes.)

In what appeared to be a move to cast doubt on the report’s findings and sidestep accountability, the president launched parallel probes overseen by allies in the Cabinet, the ANC’s parliamentary caucus, and the police, all of which exonerated Zuma of wrongdoing.

At the same time, some of the President’s allies piled verbal attacks on the Public Protector—a crime under South African law. Some of these statements were withdrawn after Madonsela threatened to exercise her power to charge them with contempt. Opposition lawmakers, fearful that the Public Protector’s findings would be ignored, petitioned the Constitutional Court on the matter. In March 2016, the Court ruled that her report was binding, that the President violated the Constitution by disregarding its findings, and that he must repay the government (the Treasury fixed the amount at around $600,000).

This ruling galvanized popular opinion. In a public letter, the late anti-apartheid icon Ahmed Kathrada urged the president to step aside.

The Public Protector’s investigations of executive branch actions have demonstrated the office to be a resilient and vital institution of accountability in South Africa.

In November 2016, the Public Protector’s office released another groundbreaking report, State Capture. This investigation uncovered wide-scale public sector corruption and influence peddling involving, among others, the Gupta family—wealthy Indian immigrants with extensive business interests in South Africa. Zuma, a close friend of the Guptas, and two cabinet ministers who were implicated in the report again took to the Court to block its release. And again, the Court found against them. State Capture orders Zuma to appoint a judicial commission of inquiry to be headed by a judge assigned by the Chief Justice. The new Public Protector, Busisiwe Mkwebane, went a step further by instructing the National Prosecuting Authority and the Justice Department’s Special Investigations Directorate to look into possible crimes.

The Public Protector’s investigations of executive branch actions have demonstrated the office to be a resilient and vital institution of accountability in South Africa.

Headquarters of the Gauteng Provincial High Court in Pretoria. (Photo: Lavinia Engelbrecht.)

The Judiciary

The efforts by the Office of the Public Protector have been supported by South Africa’s courts. In particular, the Constitutional Court’s rulings set crucial precedents by affirming the binding nature of the Public Protector’s findings. This is consistent with the reputation for independence the judiciary has established after the end of apartheid.

In the Nkandla affair, the Speaker of the National Assembly, who is also a top ANC official and close Zuma ally, argued that Parliament had exercised its constitutional oversight role by instituting its own probe into the matter. The Constitutional Court in its March 2016 ruling rejected this, saying that the National Assembly’s resolutions were unlawful because the Public Protector’s order was legally binding. The Court further noted that the Public Protector had the constitutional authority to order the President to repay some of the funds used for the Nkandla renovation.

Consistent upholding of government accountability and transparency mechanisms has shown that, like the Office of the Public Protector, South Africa’s judiciary is up to the task of acting as a check on power.

Two weeks after the Cabinet reshuffle, the Western Cape High Court ruled that the nuclear deal was illegal and unconstitutional—putting a dent in the government’s plans to move ahead with the controversial project under the new Finance Minister. Then on May 5, 2017, South Africa’s High Court demanded that Zuma justify his decision to reshuffle the Cabinet, an order that Zuma has sought permission to appeal.

Other courts have also handed down key rulings. In June 2016, the High Court rejected an appeal by President Zuma to set aside 783 charges of corruption against him dating to 2009. The ruling further barred him from making future appeals, stating that no other court will reach a different conclusion based on the facts. Zuma has nevertheless sought appeal before the Supreme Court of Appeals.

This consistent upholding of government accountability and transparency mechanisms has shown that, like the Office of the Public Protector, South Africa’s judiciary is up to the task of acting as a check on power.

The ANC and Opposition Political Parties

In mature democracies, the party in power can serve as a first line of defense against abuse since party members realize that they will suffer the long-term reputational costs from such transgressions. In fact, some of the public outcry against corruption and abuse of office has come from the ANC itself, including senior officials such as Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa, Secretary General Gwede Mantashe, Treasurer General Zweli Mkhize, and Parliamentary Whip Jackson Mthembu. The ANC’s powerful alliance partners, the South African Communist Party and Congress of South African Trade Unions, have also called on the President to resign. Meanwhile more than 100 revered elder generation anti-apartheid icons—popularly known as stalwarts—have recommended the establishment of an independent National Dialogue to take corrective action. Several foundations, including those named for Nelson Mandela, Thabo Mbeki, Desmond and Leah Tutu, Albert Luthuli, Helen Suzman, Robert Sobukwe, Jakes Gerwel, F.W. de Klerk, and Ahmed Kathrada, joined forces to establish the National Foundations Dialogue Initiative (NFDI), which held its first dialogue on May 5, 2017.

Despite these growing calls, the party’s internal mechanisms do not appear strong enough to compel Zuma to comply.

The century-old ANC prides itself on its own system of checks and balances that holds its top leaders accountable. In 2008, these mechanisms were invoked to remove former President Thabo Mbeki from office after a court found that the executive branch had interfered in an ongoing investigation. The move was unprecedented among former liberation movements. The ANC’s respected Integrity Commission, a body that independently investigates and sanctions errant party leaders summoned Zuma to appear before it in December 2016 in connection with his handling of the Public Protector’s Secure in Comfort and State Capture reports. Commission chair and struggle stalwart Andrew Mlangeni has called on Zuma to resign.

Cyril Ramaphosa. (Photo: Erfan Kouchari.)

Despite these growing calls, the party’s internal mechanisms do not appear strong enough to compel Zuma to comply. Many see this as evidence of the extent to which Zuma has coopted members and severely weakened party organs. The ANC is divided as it prepares to elect its new party president in December 2017, with Zuma’s allies coalescing around his ex-wife, Dr. Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, and reformist politicians rallying around Deputy President Ramaphosa. The latter is also backed by both the South African Communist Party and Congress of South African Trade Unions, which have broken away from the ANC’s top leadership for the first time since their alliance was forged in the 1920s.

Given the party’s failure to exercise checks and balances, many in the reformist wing appear to have set their sights on the December convention as the best avenue to overhaul its leadership. Over 4,000 delegates will be voting for more than 500 officials to fill all the party organs in what is likely to be a watershed moment for the ANC.

Opposition parties have similarly been involved in efforts to check the executive. Some landmark investigations into high-level corruption and abuse of office have been triggered by opposition petitions. The Democratic Alliance and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF)—normally on opposite ends of the ideological spectrum—have sustained pressure on Zuma, pursuing vigorous oversight in the National Assembly. Further, their outspokenness has served to educate and inform the public, as parliamentary business is covered extensively in the media.

More recently, the EFF mobilized other parties, including the ANC, to begin impeachment proceedings (the fourth attempt so far). Opposition members petitioned the Constitutional Court to order a secret ballot—a move that would allow ANC members to vote freely without fearing blowback from the party. The vote has been put on hold until the Court rules on the matter. EFF leader and former ANC member Julius Malema says that revolt within ANC ranks might lay the groundwork for bipartisan collaboration by realigning political interests around preserving South Africa’s democracy.

In short, the ANC today is fragmented, with a large cadre of members supporting Zuma’s efforts to bypass executive constraints. The party, therefore, has been unable to uphold its historical role of curbing abuses among its members.

The National Assembly

In most countries, the legislative branch serves as the primary institutional check on the executive. Despite the ANC’s dominance since 1994, the legislative branch in South Africa has earned a reputation for independence and vibrancy, setting it apart from other African legislatures that are dominated by the ruling party. This is due in part to South Africa’s proportional representation system, which was deliberately designed to increase the representation of minority parties and prevent supermajorities. The ANC currently holds 249 seats in the National Assembly, while the combined opposition controls 151. In 2009, a further safeguard against supermajorities was established when “floor crossing”—changing allegiances after election—was outlawed. The National Assembly’s reputation for rigorous oversight was reinforced by investigations, overseas visits, and legislation conducted by joint teams of ruling and opposition party officials.

Recently, however, this tradition has given way to patterns of partisanship and acrimony that stand in stark contrast to established parliamentary practice. The move by ANC deputies to institute a parallel probe into the Nkandla matter to supplant the Public Protector’s investigation is emblematic of that trend. In 2016, the ANC deputies quashed a motion by the opposition to establish a multiparty committee to look into the findings of the State Capture report, arguing that other institutions were more competent to do so.

The National Assembly’s role as an independent check has been further undermined by an increase in open hostility during parliamentary proceedings. Some of this rancor has led to name-calling, profane language, threats of violence, and even physical brawls. In February, EFF lawmakers interrupted Zuma’s State of the Nation address, calling him “rotten to the core.” Amid the ensuing tirade of insults traded across the aisle, a fist fight broke out, and security guards had to be called in to eject the instigators.

This confrontation reflects the inability of the National Assembly to serve as an effective check on executive power. It is also symptomatic of South Africa’s increasingly polarized political atmosphere that has further fueled public anger.

President Jacob Zuma replies to questions in Parliament. (Photo: GCIS)

Civil Society

The anti-apartheid struggle instilled a strong tradition of activism, community organizing, and political mobilization in South Africa. Citizens’ awareness of their rights and responsibilities is high and explains their ability to mobilize dissent and express their views.

The investigation leading to the State Capture report was triggered by three separate complainants: the leader of the official opposition, a Catholic priest, and a private citizen whose identity is protected. The fact that two individuals with no political connections sought redress in this way underscores the public’s involvement in national politics. Media reports are what first brought the Nkandla affair to national attention, and trade unions have played a major role in disseminating information, promoting public debate, and applying pressure.

Civil society’s role as a watchdog and the unification of differing interest groups will be crucial as South Africa works to preserve its democratic traditions.

Civil society’s role as a watchdog and the unification of differing interest groups will be crucial as South Africa works to preserve its democratic traditions. It also provides a lesson on how citizens in democracies become active participants in shaping their nation’s future.

South Africa is at a crossroads. While some of its institutional checks and balances have been vigorously resisting executive overreach, others have been coopted or have proven too feeble. The outcome of this struggle remains unclear—and with it implications for the quality of South Africa’s democracy.

Africa Center Experts

- Daniel Hampton, Chief of Staff and Professor of Practice, Security Studies

- Godfrey Musila, Research Fellow

- Joseph Siegle, Director of Research

Additional Resources

- Richard Goldstone, “The First Years of the South African Constitutional Court,” Supreme Court Law Review, York University, Volume 4, 2008.

- Richard Calland, “Stakes for South Africa’s Democracy Are High as Zuma Plunges the Knife,” The Conversation, March 31, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Africa and the Arab Spring: A New Era of Democratic Expectations,” Special Report No. 1, November 30, 2011.

More on: Democratization Governance Rule of Law South Africa