DRC election officials prepare to count ballots in the 2011 election. (Photo: MONUSCO/Myriam Asmani)

The presidential elections in the Democratic Republic of the Congo initially scheduled for December 23 and since postponed, already being held two years past the end of President Joseph Kabila’s constitutionally mandated second term in office, face serious credibility challenges. Hoped-for improvements in security and stability that could be realized with the election of a legitimate government, therefore, are at risk. As the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa, located in the heart of continent, growing instability in the DRC has tangible security implications for all nine of its neighbors.

Why Are These Elections so Important?

Joseph Kabila became president upon the assassination of his father, then-President Laurent Kabila, in 2001. The latter had come to power through a Rwandan-backed insurgency that toppled longtime strongman Mobutu Sese Seko. The younger Kabila was then elected to the presidency in 2006 and again in highly controversial 2011 elections. Due to term limits, elections were supposed to be held in 2016 but the Kabila government repeatedly stalled in organizing them. Kabila has, in turn, used this as a justification for remaining in power.

Accordingly, many Congolese dispute the legitimacy of the sitting government. The perceived power grab has been a trigger for the formation of many of the estimated 70 armed groups that have emerged around the country. Given the weakness of the Congolese state, a further escalation of fighting could have highly destabilizing and long-lasting consequences. Indeed, the Congolese wars of the 1990s and early 2000s killed an estimated 5.4 million people and involved eight neighboring countries. Credible elections are seen as one of the last opportunities to reverse this looming threat.

The Kabila administration, furthermore, is widely perceived to be corrupt. Transparency International ranks Congo 161st out of 180 in its 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index. Kabila and his immediate circle are known to control large parts of the country’s vast mineral resources. According to Global Witness, more than $750 million in mining revenues never made it into state coffers between 2013 and 2015 alone. Rather, a large percentage of the money ended up in accounts owned by regime insiders.

Laying the Groundwork for a Pre-Determined Outcome

Kabila has been setting the stage to maintain his influence and ensure a favorable outcome for this election for years. Just before the 2011 elections, the rules were changed to a single round format, enabling a candidate to win with only a plurality of votes—and allowing Kabila to claimed victory. This system is likely to be pivotal again in 2018 given ongoing divisions within the opposition, which is fielding 19 candidates.

Kabila has also maintained control of the transition process. Following the expiration of his term in December 2016, citizens have repeatedly taken to the streets, not only in Kinshasa but also in in Boma, Goma, Matadi, and Lubumbashi, to demand that elections be held and that Kabila step down. Security forces have repeatedly cracked down on these protests, killing more than 100 civilians.

Some observers argue that the current system will allow Kabila to install Shadary for one term before returning to the presidency for a permitted third term.

To head off further destabilization, the influential National Episcopal Conference of Congo (CENCO), a council of Catholic bishops, brokered a New Year’s Eve agreement between the ruling party and opposition calling for a transition process leading to elections in December 2017. The transition period was to be run by a prime minister from the opposition. However, Kabila was able to delay, coopt, and ultimately negate this process, causing CENCO to withdraw its support for the agreement in March 2017.

Kabila has also attempted to tilt the outcome by limiting the participation of popular opposition candidates by altering the rules on eligibility. This process excluded six potential candidates, including the former governor of Katanga, Moïse Katumbi, and former rebel group leader Jean-Pierre Bemba.

In August 2018, he announced as his chosen successor Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, a former Minister of the Interior who is under EU sanctions for his role in repressing political dissent. Kabila intends to remain leader of the People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD). Some observers argue that the current system will allow the 47-year-old Kabila to install Shadary for one term before returning to the presidency for a permitted third term since the two consecutive term limit clock will have been reset.

Obstacles to Legitimate, Free, and Fair Elections

There are multiple operational obstacles to holding elections in a credible manner. The resulting ambiguity provides further leverage for the ruling party to generate a favorable result.

First is security. Dozens of armed groups active around the country pose a threat to the ability of some of the 46 million registered voters to cast their ballots, particularly in the unstable east and center of the country. With the campaign officially underway, security forces have limited opposition rallies and travel. On December 12, for example, two people were killed when security forces fired live rounds on supporters of opposition candidate Martin Fayulu in Kalemie. The day before in Lubumbashi, security forces dispersed his supporters using tear gas and water cannons. Fayulu’s plane has also been denied landing rights multiple times. On December 19, the governor of Kinshasa, a member of the presidential coalition, announced that campaigning inside the capital would be suspended for security reasons, thereby preventing Fayulu from holding a long awaited rally.

Early on December 13, a fire broke out in a CENI warehouse in Kinshasa, an opposition stronghold. The flames destroyed the materials needed to vote in 19 of the capital’s 25 polling places. Also lost in the blaze, according to a CENI press statement published just 6 hours after the incident, were 8,000 voting machines out of 10,368 required for the jurisdiction plus 3,774 voting booths out of 8,887 needed. In justifying a further delay to the vote, the CENI president explained that while the machines had been replaced as of December 20, coding the new machines would require a few additional days. Moreover, some paper ballots and the remainder of the tally sheets would only arrive on December 22 and would then need to be deployed across the country.

The logistical challenges associated with organizing elections in the DRC are numerous, and the government has amplified them through several actions including refusing international assistance, in particular logistics help from the UN mission. In both 2006 and 2011, UN missions (MONUC in 2006 and MONUSCO in 2011) played an essential role in opening, staffing, and delivering ballots by air. In both cases, the mission helped to open more than 60,000 polling stations. This time, the DRC government and CENI say they will do it on their own.

The lack of transparency in the process of organizing the vote has also been hampered by the fact that the Kabila government has refused to allow some outside observers, in particular from international election observer groups such as the Carter Center, the National Democratic Institute, the EU, and South Africa. The Kabila government has allowed observers from the African Union (AU), the Organisation internationale de la francophonie (OIF), and Southern African Development Community (SADC).

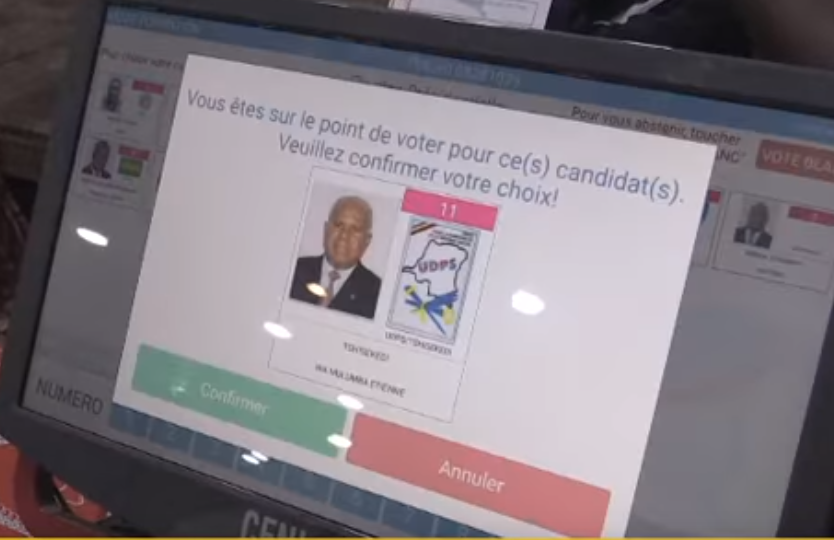

A DRC voting machine. (Photo: Africanews)

The government has permitted the Catholic Church’s Peace and Justice Commission and local groups organized under the civil society coalition, Synergie des missions d’observation citoyenne électorale, to provide 40,000 and 20,000 observers respectively. However, even if that many could be deployed, they still wouldn’t be enough to monitor the vote in the country’s more than 80,000 polling places. In addition, the AU and SADC are both perceived to favor the regime. The OIF hasn’t fielded observers in decades and has instead proposed to train a small number of Congolese for this purpose.

Observers have also expressed concern that too few voting machines have been purchased, that each voting station will only have one spare machine, and that there is no backup plan for casting ballots in case the machines don’t work. Moreover, given the expected voter turnout and its ratio to available voting machines, voters will only have about one minute each to cast a vote for the multiple elections that are being held that day. Since Congolese voters have never used such machines before, confusion is likely. Critics also say that given this lack of familiarity, voters’ right to a secret ballot could be jeopardized.

The police and army, which are tasked with securing voting stations could also play a role in influencing voters. Security forces are widely perceived to be politicized and cannot be counted on to execute their duties in a neutral manner as UN peacekeepers have in the past As the Forces armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) are clearly tied to the government’s patronage networks, they have a vested interest in the status quo.

Lack of Trust in CENI and Its Ability to Organize Credible, Free, and Fair Elections

The DRC electoral commission (CENI). (Photo: Africanews)

CENI’s independence is seen as questionable given its history and composition. The six-member board continues to be the main operational organ. While designed under the CENCO agreement to be a balanced body, Kabila has been able to coopt designated members of the opposition effectively giving himself control. CENI chair Corneille Nangaa is seen as a Kabila loyalist. A recent survey conducted by the Congo Research Group found that 64 percent of responders don’t trust CENI and 74 percent don’t trust its chair.

The accuracy of the electoral roll and the means of casting votes have also been criticized by independent observers. While the OIF conducted an audit of the voter roll in May 2018, it found that it could still be significantly improved. A separate assessment by international elections oversight groups estimates that anywhere between 6 and 14 million people could illegally cast ballots, particularly if CENI decides to allow voters to cast ballots outside their normal polling place, as it did in the 2006 and 2011 elections. This has implications on many levels because the number of voters in a country that hasn’t had an official census since 1984 determines how many seats in parliament each area gets and what size the regional parliaments should be. Inflating the rolls, especially if the inflation is concentrated in certain political strongholds, could have severe repercussions for the legitimacy of the legislature.

Similarly, CENI’s decision to use voting machines—in this case touch screen tablets that will also print out a paper ballot—has decreased confidence in the elections, particularly among the opposition who argue that the machines will facilitate fraud, as well as the contract for delivering the machines themselves, was fraught with controversy.

Observers and members of the opposition fear that any one of these challenges or combination thereof could successfully be used by the government to alter the outcome of the election to the benefit of the ruling party.

Potential Fallout and Reinforcing Norms

CENCO, which is seen as one of the most legitimate organs of Congolese civil society, has expressed numerous concerns about the polls and asked that the results be certified by international and national experts. It has also requested that the machines be used sparingly (to identify voters) and to conduct a manual count of votes. In addition, CENI should post the results in each polling station and count the votes to facilitate transparency, verification, and reduce the scope of rigging.

The response from regional and international actors will have implications for governance norms elsewhere in Africa.

Regional actors, including South Africa, Angola, the AU, and SADC have all played different roles in the run up to the elections. The AU and SADC are widely seen as favoring the ruling party since neither encouraged Kabila to step down after his term expired, requested a transitional administration until elections could be held, or even threatened sanctions on him and his administration for ignoring the end of his constitutional term. South Africa and Angola have taken a more public role, making clear that they would not support Kabila running again. South Africa in particular has twice convened the opposition to try to find a unity candidate. This represents a change in position for the country, which until Cyril Ramaphosa became president, was more supportive of Kabila. Angola meanwhile has publicly pushed Kabila to step down and made clear to Kabila that staying in power would increase instability.

Other external stakeholders have a role to play in protecting the space civil society needs to provide independent oversight and a parallel vote count. In addition, media and observers should heed the lessons of recent elections in Kenya and Zimbabwe and take their time before endorsing the polls and calling them free and fair. International actors must also guard against endorsing elections on an “African curve,” rather than on higher standards that are expected in other parts of the world.

Independent election observers should also be sure to include in their reporting results for those candidates whose parties do not meet the 1 percent threshold for official recognition in parliament. Doing so will help to determine exactly how much of the vote opposition candidates actually won.

Surveys show that strong majorities of African citizens favor democracy as their preferred system of government.

In the event of a declared victory for Shadary, who polls show is drawing just 16 percent of the vote, it is extremely likely that Congolese will take to the streets to protest. If the protests that have occurred since Kabila refused to step down are any predictor, these will be met with violence from the security forces. International stakeholders, including the AU, SADC, OIF, EU, and key bilateral partners will therefore need to consider how they will respond to such a flawed process. The stances they take will shape perceptions of their commitment to democracy. This is especially true of the AU, which has seemingly retreated from the commitment to democratic principles articulated in the African Charter on Elections, and Governance signed and ratified by 31 of its members.

The response from regional and international actors will have implications not only for security and stabilization in the DRC but also for governance norms elsewhere in Africa. Over the years, some progress has been made in ensuring that elections in Africa are in fact free and fair. However, ruling parties have become even more proficient at maintaining the trappings of elections while controlling the outcomes. This perpetuates a dynamic of illegitimacy and instability.

The counterpoint to this dynamic is that Afrobarometer surveys show that strong majorities of African citizens favor democracy as their preferred system of government. Among other things, this reflects their experiences of instability generated from political systems based on exclusion and inequality that keep leaders in power indefinitely. The question remains whether such democratic aspirations in the DRC can come about through the ballot box—or via other means.

Africa Center Experts

- Alix Boucher, Assistant Research Fellow

- Paul Nantulya, Research Associate

Additional Resources

- Paul Nantulya, “Stability in the Democratic Republic of the Congo beyond the Elections,” Spotlight, November 28, 2018.

- Jason Stearns, “The Politicization of Electoral Institutions,” Congo Research Group, November 1, 2018.

- Susan Dosworth, “Double Standards, the Verdicts of Western Elections Observers in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Democratization, October 2018.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Catholic Church Increasingly Targeted by Government Violence in the DRC, Spotlight, March 27, 2018.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Term Limits for African Leaders Linked to Stability,” Infographic, February 2018.

- Paul Nantulya, “A Medley of Armed Groups Play on Congo’s Crisis,”Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Spotlight, September 25, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2016 Spotlight Series on the Democratic Republic of the Congo:

- Part 1: “A Looming Calamity in the Democratic Republic of the Congo”

- Part 2: “The DRC’s Oversight Institutions: How Independent?”

- Part 3: “The Role of Civil Society in Averting Instability in the DRC”

- Part 4: “Security Sector Institutions and the DRC’s Political Crisis”

- Part 5: “The Role of External Actors in the DRC Crisis”

More on: Democratization Democratic Republic of the Congo