An electoral official in Anambra State, Nigeria. (Photo: AFP)

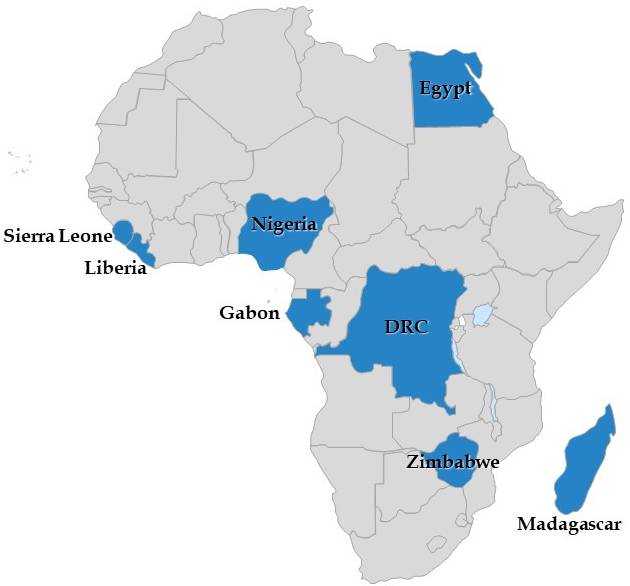

Spanning West, Central, North, and Southern Africa, the eight elections in Africa this year comprise some of the most populous countries on the continent. This includes Nigeria, which kicks off the electoral calendar in February, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with elections slated for late December. Collectively, the countries selecting national leaders in 2023 represent roughly a third of the continent’s population.

In five of the elections (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Madagascar, Sierra Leone, and Zimbabwe), incumbents are seeking a second term. There is only one open seat, in Nigeria, as President Muhammadu Buhari steps down after his constitutionally mandated second term.

There is a broad spectrum of trajectories in which these elections may lead. Some provide crucial opportunities for consolidating democratic progress. Others face uneven electoral playing fields and must overcome institutional legacies of one-party rule.

In every case, there are illustrations of democratic resiliency. This is seen in the actions of civil servants, judges, political parties, citizen groups, security professionals, and journalists—who, often at great risk, collectively aspire to strengthen and uphold norms of civic discourse, popular participation, and fairness. This is particularly evident in the dynamic role that youth are playing in many of these elections—a reminder that 70 percent of Africa’s population is under the age of 30.

Given the central role that governance plays in security in Africa, the stakes from these elections are high—not just for democracy but for stability and development. Since governance norms, insecurity, and economic dynamism are rarely contained by borders, the conduct and outcomes from each of these elections will also have implications for their neighbors and the continent overall.

Here are some of the key issues to watch.

Nigeria

Nigeria

Presidential and Legislative, February 25

The electoral context in Africa’s most populous country and largest economy is characterized by juxtaposing forces of deteriorating security alongside substantive efforts to maintain the trajectory of electoral reforms that Nigeria has realized for every election since its reintroduction of multiparty democracy in 1999.

The security environment is typified by a diverse array of challenges ranging from militant Islamist groups continuing their destabilizing attacks in the northeast to the widespread criminal banditry and violence in the northwest, farmer-herder violence in the Middle Belt, separatist agitation in the south, persistent attacks on the country’s oil infrastructure, maritime insecurity, and police violence. Estimates are that 10,000 Nigerians died from violent attacks in 2022 and another 5,000 were abducted. Daily incidents of highway robberies and kidnappings for ransom are contributing to a growing sense of lawlessness to the point that Nigeria’s Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) has warned that insecurity could cause a postponement in the election.

“The race is competitive and the outcome unpredictable—a further indication of Nigeria’s democratic progress.”

Parallel to the heightened security concerns, notable electoral reforms are underway. The Electoral Act of 2022 allows electronic voting and transmission of election results that are expected to improve transparency and reduce opportunities for vote rigging. It also mandates the recording of ballots at Nigeria’s 176,000 polling stations prior to their transmission to Abuja. This electoral best practice, prominently displayed in Kenya’s 2022 presidential elections, allows real-time monitoring of electoral results by citizens and watchdog groups, increasing the integrity of the process. Based on the successes of off-cycle elections in Ekiti and Osun States in 2022, INEC Chairman, Dr. Mahmood Yakubu, has said that Nigeria’s 2023 elections will be the most transparent yet.

Two establishment and two upstart candidates are vying to replace President Muhammadu Buhari. The 80-year-old Buhari is stepping down after his constitutionally limited second term, another notable but widely overlooked feature of the Nigerian elections given the recent propensity for term limit evasion on the continent. A former governor of Lagos State (South West region), Bola Ahmed Tinubu, is the standard bearer for the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC). Six-time candidate and second place finisher to Buhari in the 2019 election is Atiku Abubakar of the long-dominant People’s Democratic Party (PDP) who hails from Borno State in the North East region. Both Tinubu and Abubakar are in their seventies and represent a continuity in the established party structures.

A novel development in the 2023 electoral cycle has been the emergence of two other serious challengers on the electoral landscape. A successful entrepreneur and former governor of Anambra State (South East region), Peter Obi, is the Labour Party’s presidential candidate. Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso, a former Kano State (North West region) governor and senator as well as a former federal minister of defence, heads up the New Nigeria Peoples Party (NNPP).

A Labour Party rally in Abuja, September 2022. (Photo: AFP/Kola Sulaimon)

Nigerian parties have historically alternated putting forward candidates from the north and south of the country out of recognition of the country’s fragile and evenly balanced Muslim-Christian composition and ethnic diversity. The APC has followed this tack with Tinubu coming from the south, given Buhari’s northern roots. With Abubakar also originating from the north, the PDP is disregarding this norm. At the same time, Tinubu, a Muslim, has selected as his vice-presidential running mate former Borno State Governor Kashim Shettima, another Muslim. This breaks another norm of ensuring religious balance on the ticket. By contrast, Abubakar has selected Ifeanyi Okowa, a Christian and current Delta State Governor as his vice-presidential choice. It remains to be seen how much weight voters will give these traditions—or whether citizens believe that Nigeria’s democracy has matured enough that it need not maintain these ticket balancing principles.

While the experience and vote mobilizing infrastructure of the established parties provide them an edge, the race is competitive and the outcome unpredictable—a further indication of Nigeria’s democratic progress. The established parties, APC and PDP, are also likely to have an advantage at the state-level elections in Nigeria’s highly decentralized federal system. All 109 Senate seats and 360 House of Representative seats are up for election. Meanwhile, half of all 36 State governors are stepping down this electoral cycle, portending potentially significant changes in leadership at all levels of the Nigerian government.

Presidential candidates must win 50 percent of the national vote and at least 25 percent of the vote from at least 24 of Nigeria’s 36 States to secure victory. Should candidates fail to achieve a majority on the first round, the top two candidates will face off in a second round. Given the competitiveness of this year’s race, this is seen as a real possibility and would be a first for Nigeria.

“Youth unemployment is more than 50 percent, and youth comprised 75 percent of the 9.4 million newly registered voters.”

The electoral outcome may hinge on the mobilization of the youth vote. The median age in Nigeria is 18, and more than 40 percent of the 94 million registered voters are under the age of 35. Youth unemployment is more than 50 percent, and youth comprised 75 percent of the 9.4 million newly registered voters. Digitally savvy and building on their driving role in the #EndSARS police reform protests, Nigerian youth are highly motivated for this electoral cycle and indications are that they are most receptive to the calls, particularly by Peter Obi, for greater government responsiveness to citizen priorities and enhanced transparency.

The Nigerian elections, in short, will be a test on multiple levels. First will be whether the electoral reforms that have been instituted contribute to an outcome that most Nigerians view as credible. Second will be whether the mechanisms of democratic self-correction—the opportunity to switch leaders and policies to adapt to shifting circumstances—will work sufficiently to identify and empower Nigeria’s new leader with the legitimacy and vision to enable one of Africa’s most vital countries to chart a new course forward to address the serious security and economic challenges it faces.

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone

Presidential and Legislative, June 24

President Julius Maada Bio is seeking a second 5-year term in 2023. Despite a legacy of competitive elections and peaceful transfers of power, Sierra Leone enters this election season under the strain of heightened economic and political tensions.

With a per capita income of $500 and roughly 60 percent of the population falling below the poverty line, this country of 8.6 million people has been particularly vulnerable to the economic shocks caused by the COVID pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Inflation has risen to 30 percent over the past year, while food prices have increased by 50 percent and fuel costs have doubled. This has caused enormous strains for the majority who have little buffer to meet their daily needs. Nearly three out of four Sierra Leoneans are food insecure. Finding it difficult to make ends meet, doctors and teachers have gone on strike for pay increases.

Election officials in Sierra Leone in 2018.

(Photo: The Commonwealth)

Protests are relatively uncommon in Sierra Leone, and political protests require a police permit, which is rarely granted. Nevertheless, in August 2022, there were protests against the growing economic hardships triggering a brutal police crackdown, including the firing of live ammunition at protesters that resulted in 21 civilian and 6 police fatalities. Businesses, government buildings, and vehicles were charred across parts of eastern Freetown.

Political tensions have been elevated since the 2018 legislative elections when Bio’s Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) party challenged 10 seats won by the opposition All People’s Congress (APC). In 2019, the High Court ruled in favor of the SLPP petition alleging electoral fraud. As a result, the contested seats automatically shifted to the runner-up SLPP candidates. This resulted in a flipping of the majority in the unicameral legislature to the SLPP by a 58 to 57 margin.

APC supporters protested the court ruling outside the court and their party headquarters. Police subsequently laid siege to the party building, firing tear gas to break up the demonstration.

“Critics are concerned that a proportional representation system will further concentrate power in the hands of party leaders.”

A new wrinkle in the 2023 legislative elections is that they will be run under a proportional representation (PR) rather than the customary constituency-based first-past-the-post electoral system. The APC had challenged the legality of the change put forward by the SLPP, however, the Supreme Court ruled in January 2023, that the shift in voting system was constitutional. Critics are concerned that a PR system will further concentrate power in the hands of party leaders.

This change, just 5 months before the election, will require parties to adjust their campaigns while introducing a new element of uncertainty. While it has reputation for fairly administering its duties despite financial limitations, the revised selection procedures will also require rapid adaptation by the National Election Commission.

Bio came into office in 2018 after defeating Samura Kamara of the incumbent APC party with 52 percent in the second round of voting in a process deemed credible by international observers. Bio succeeded his term-limited predecessor President Ernest Bai Koroma of the APC. Koroma, in turn, was following the precedent of President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah of the SLPP, who stepped down in 2007 after his two terms in office. Sierra Leone, thus, has made commendable strides in building democratic institutions and maintaining stability since its devastating civil war from 1991-2002 in which 50,000 people were killed.

A former brigadier general, Bio was briefly the head of a military junta prior to Kabbah’s taking office in 1996, beginning Sierra Leone’s democratic transition. Bio subsequently contested the 2012 presidential campaign, losing to Koroma.

Sierra Leone president Julius Maada Bio. (Photo: Tom Witham)

As a candidate, Bio railed against corruption, an endemic problem in Sierra Leone. Once in office, he consolidated all treasury accounts, reducing leakage of government spending while increasing revenues. He also launched the Anti-Corruption Commission, which has filed charges against several senior officials from the Koroma administration, further fueling political tensions between the parties.

In 2021, Bio suspended and has tried to subsume the independence of the Audit Service Sierra Leone (ASSL) after it released findings of corruption and fraud under his administration in its annual government audit (as it had for the previous Koroma government). The respected Auditor-General of the ASSL, Lara Taylor-Pearce, is fighting the suspension in court, contending that Bio does not have the authority to interfere with the ASSL as it is an independent oversight body.

During Bio’s tenure, the legislature has repealed the highly restrictive libel and sedition law creating more space for independent media. The law had been used to target journalists reporting on elections and corruption. The SLPP-led National Assembly has also repealed the death penalty.

The APC has selected Samura Kamara to represent the party, setting up a rematch of the last presidential election. Given the parity between the two major parties, the 2023 elections are likely to be tightly contested. Bio has the advantages of incumbency. However, he will need to overcome stiff economic headwinds coupled with the opposition’s mobilization against his and the SLPP’s perceived overreach of political authorities.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Presidential and Legislative, August 23

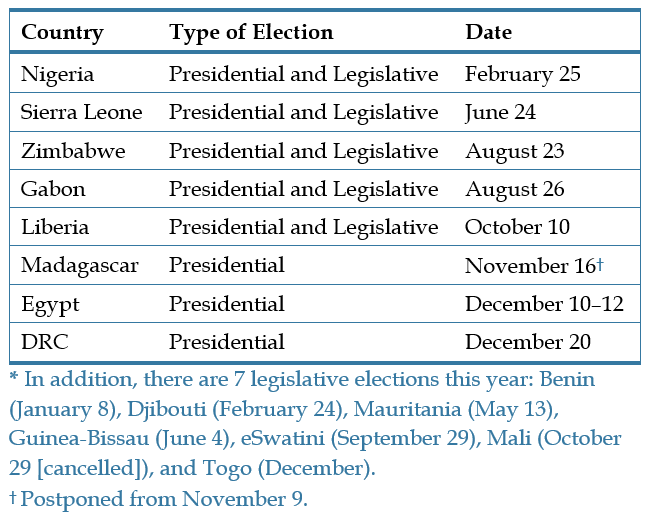

The Zimbabwean elections are shaping up to be the bloodiest on the continent this year as the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) ramps up its use of violence and intimidation in the attempt to retain its 43-year grip on power.

The latest cycle of violence against opposition candidates has, in fact, already begun. In June 2022, opposition activist Moreblessing Ali was abducted on the outskirts of Harare. Her dismembered body was later found in a well nearby. Witnesses identified a ZANU-PF activist as the assailant. Over a dozen opposition politicians who attended her funeral were arrested for “inciting violence.” Many remain incarcerated even though they have yet to be charged.

“The deployment of political violence in Zimbabwe continues a decades long pattern.”

This is but one illustration of the pattern of intimidation and suppression of political opposition, including arrests and extrajudicial killings, that Zimbabwe faces as it heads toward elections.

ZANU-PF has held a stranglehold on the presidency since Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980. Seven-term president/prime minister, Robert Mugabe, was ousted in a 2017 coup by former army chief, General Constantino Chiwenga. ZANU-PF continuity was retained with the installation of former Vice-President Emmerson Mnangagwa as President. Chiwenga defended the unconstitutional exercise by saying, “when it comes to matters of protecting our revolution, the military will not hesitate to step in.”

Mnangagwa was subsequently declared the victor of the widely criticized 2018 election with 50.8 percent of the vote. Chiwenga is now Vice-President.

The deployment of political violence in Zimbabwe continues a decades long pattern—from the liberation movement days known as “Chimurenga.” It was marked by incidents such as the Matabeleland massacre in the 1980s, the mysterious killings of rival politicians inside and outside of ZANU-PF, and the multiple beatings longtime opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai suffered in the effort to unseat Mugabe.

What is noteworthy in the 2023 cycle is how early the violence against the opposition has started. The faction now in control of the ZANU-PF is also increasingly dropping any pretense that violence is not part and parcel of the party campaign playbook. This may reflect the more central role the military has played in the party since the coup. While the ZANU-PF governing model has long been built around a politicized military, known as “securocrats,” this relationship has fostered fraught civil-military relations that pose a formidable obstacle to democratic progress. Today, security officials are routinely indoctrinated in ZANU-PF’s Chitepo School of Ideology.

A Zimbabwe police officer chasing a protester in 2005. (Photo: Sokwanele)

The increasingly harsh methods used against the opposition may also reflect lessons Mnangagwa learned as head of the Joint Operations Command under Mugabe, which the latter used to target political rivals with abductions, arrests, and killings. Mnangagwa has been under U.S. sanctions since 2003 for “contributing to the deliberate breakdown in the rule of law.”

With this climate of violence and intimidation, it is a given that the elections will not be free and fair.

This perspective is reinforced by widely held perceptions that the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) is biased, with leading ZANU-PF family members serving as commissioners. ZEC’s reputation also suffers from the outsized role of the military, where 15 percent of ZEC staff are former service personnel, including the chief elections officer, who is a retired army major. Contrary to electoral best practice, ZEC has refused to publish an electronic copy of the electoral register to foster transparency.

This pattern of institutional bias builds on a long history of election engineering in Zimbabwe including: limiting the number of polling stations in opposition strongholds, challenging the credentials of opposition candidates, and filing criminal charges against others—all with the aim of preventing them from standing for office.

An illustration of the latter is the imprisonment of Fadzayi Mahere, a 36-year-old lawyer and opposition member of Parliament with half a million Twitter followers. She was charged with “communicating false statements prejudicial to the state.”

Despite this lopsided electoral playing field, ZANU-PF may still lose.

The antipathy many Zimbabweans hold toward the party is so strong that it will be difficult for ZANU-PF to credibly claim an electoral majority. Should the electoral results and public sentiment become so overwhelming, ZANU-PF may be forced to accept defeat. This was the choice faced by President Edgar Lungu in neighboring Zambia in 2021 and President Joseph Kabila of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and his handpicked successor in 2018.

The repressive climate has contributed to a unified and resilient opposition under the banner of Nelson Chamisa and his Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC) party. After ZANU-PF appropriated the name and assets of the longtime leading opposition party, Movement for Democratic Change, the newly organized CCC won 19 out of 28 parliamentary seats in by-elections held in 2022, including in Mnangagwa’s home district of Kwekwe Central. CCC also won a majority of local council seats it contested despite adversarial state media coverage and intimidation tactics by ZANU-PF.

“Zimbabweans have seen a return of the hyperinflation of the 2000s. Inflation now stands at around 250 percent and is expected to escalate.”

The CCC also offers hope for economic stabilization. With the government having abandoned the peg to the U.S. dollar (USD) in 2019 and the unregulated printing of currency to meet financial obligations, Zimbabweans have seen a return of the hyperinflation of the 2000s. Inflation now stands at around 250 percent and is expected to escalate. The value of the Zimbabwe dollar (ZWL) has sharply dropped. It now trades at 900 ZWL to 1 USD versus 200 to 1 in 2021.

Nearly half of the population has fallen into poverty over the past decade. Rolling power outages regularly last for 20 hours per day. Unemployment stands at roughly 90 percent, and more than two-thirds of Zimbabweans earn their livelihoods from the informal sector. The prolonged economic crisis has caused an estimated 3 million Zimbabweans (out of a total population of 16 million) to flee the country, most to neighboring South Africa.

This economic hardship is juxtaposed with the perception that ZANU-PF and security leaders benefit from sole-source contracts and exclusive mining access, while sheltering their assets from inflation via offshore accounts. Anjin, a Chinese diamond mining firm with close ties to the Zimbabwe military, has been invited back into the country after having been expelled in 2016 for having “looted” the country of $15 billion, according to then-President Mugabe.

The opposition’s track record for monetary and fiscal probity is also fueling support. It was only when the then-opposition MDC gained control of the Ministry of Finance under an awkward power-sharing deal between 2009-2013 that the previous bout of hyperinflation was brought under control. Responsible monetary policy and greater transparency re-instilled confidence in the economy, precipitating an economic turnaround.

Hopes for progress also rest on resilient democratic norms among the populace. Judges have regularly thrown out government charges against opposition politicians as lacking merit. While the track record of judicial independence is uneven, it has been sufficient to enable the opposition to take their grievances to the courts rather than resort to violence.

Emerson Mnangagwa.

(Photo: kremlin.ru)

Mnangagwa’s ZANU-PF has tried to rein in the independence of the judiciary with constitutional amendments in 2021 that would allow the president to extend the terms of select senior judges as well as appoint judges instead of subjecting them to a public vetting process as has been the norm. However, Zimbabwe’s High Court has ruled these amendments unconstitutional. This is significant since Mnangagwa is seeking to extend the term of Chief Justice Luke Malaba, who had dismissed the opposition’s petition to annul the 2018 election for election rigging.

Similarly, despite persistent intimidation, the media has maintained a degree of independent reporting. Journalists like award-winning Hopewell Chin’ono have been regularly arrested and imprisoned under harsh conditions for exposing government corruption.

Nelson Chamisa. (Photo: Zviko Zingoni)

As in other African polities, the Zimbabwean election also represents a generational battle for the future of the country. An octogenarian, Mnangagwa represents the status quo of one-party rule, while 44-year-old Chamisa captures the democratic and reformist aspirations of millions of Zimbabwean youth. Roughly 62 percent of the Zimbabwean population is below 25 years of age.

The election also pits the more urban and educated supporters of the opposition against the largely rural base of ZANU-PF who benefit from food and social welfare support in proportion to their party loyalty.

The Zimbabwean election may also turn on the support of external actors. China has a longstanding relationship with ZANU-PF and is a major creditor, even though Zimbabwe has defaulted on some of its loans and refused to pay others. This relationship has afforded China privileged access to diamond and mining interests in Zimbabwe. Through its sponsorship of disinformation campaigns, Russia is also a candidate to help sustain ZANU-PF’s hold on power as a means of advancing Russian political and economic influence.

While the deck is stacked high in favor of ZANU-PF, the legitimacy of the party and the securocrat state it governs rests on a house of cards—and therefore it persists in a perpetually fragile state.

Gabon

Gabon

Presidential and Legislative, August 26

Gabon’s 2023 presidential elections are expected to be a tightly controlled affair leading to the predictable outcome of President Ali Bongo Ondimba’s continuation in office. With the abolishment of term limits in 2003, Bongo is effectively president for life. It is a mantle he inherited in 2009 from his father, Omar Bongo Ondimba, who held the office for 42 years, reflecting the de facto hereditary dynasty of this oil-rich realm in the heart of the Congo Basin rainforest.

Executive branch control over the institutions responsible for elections—the National Autonomous and Permanent Electoral Commission, the Interior Ministry, and the Constitutional Court—directly contributes to the predictability of electoral outcomes. The discretionary approach toward elections was evident in the repeatedly postponed National Assembly elections that were held in 2018 after originally being planned for 2016.

“With the abolishment of term limits in 2003, Bongo is effectively president for life.”

For an extra cushion of executive authority over the legislative branch, a constitutional amendment in 2020 authorized the president to appoint 15 members of the expanded 67 seat Senate—even though the ruling Gabonese Democratic Party (GDP) already controlled 45 of the 52 seats in the upper chamber. The ruling party’s parliamentary majority facilitated an additional amendment in 2023 that reduced the presidential term from seven to five years and turned all elections into a single round of voting, after a two-round system had been added to the Constitution in 2018. The latter change enables the ruling party to retain power absent an absolute majority, further lowering the bar it must clear.

Despite the executive control over the levers of electoral machinery, the government keeps a tight leash on the opposition. Permits for public gatherings are frequently denied and leaders are arrested. Sosthène Orphée Lendjedi Ibola, a 2023 presidential candidate for the Orientation Nouvelle (“New Orientation) party who had recently returned from 6 years of exile in North America, was arrested in November 2022 on charges of fomenting terrorism. Similarly, while convictions of government officials for corruption are rare, anticorruption campaigns are often used to target political opponents.

Protests over the 2016 presidential election, which was widely seen as fraudulent, resulted in the raiding of the headquarters of the main opposition candidate and former African Union Commission Chairperson Jean Ping. Estimates are that more than 50 people were killed and hundreds more arrested. The episode is a reminder of the simmering discontent even in a seemingly stable, middle-income authoritarian country.

Voters cast their ballots in Libreville, Gabon, in 2016. (Photo: AFP)

While episodes of violent repression persist, the GDP appears to prefer using its leverage over the political system to disrupt the opposition. Toward this end, the GDP has successfully coopted several potential 2023 presidential rivals into the ruling party, leaving the opposition fragmented. Similarly, rather than arbitrary arrests, the state media regulator, the High Authority for Communication, regularly suspends journalists and outlets that are critical of the government or expose corruption, contributing to self-censorship.

Corruption is a sensitive issue for the population of 2.3 million. Despite being Africa’s fourth largest oil exporter and a per capita income of $8,635, a third of the population faces poverty. Gabon ranks 124 out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, and the trendline has been declining for the past decade. Global investigative reporting that produced the Pandora Papers—a leak of almost 12 million financial documents of the world’s most rich and powerful—linked the Bongo family to opaque financial dealings. An investigation in France alleges BNP Paribas of money laundering in support of the Bongo family. Civil society organizations in Libreville subsequently filed a lawsuit in 2020 accusing the President’s 30-year-old son, Noureddine Bongo, of corruption, charges which were dismissed by the public prosecutor.

“Despite being Africa’s fourth largest oil exporter and a per capita income of $8,635, a third of the population faces poverty.”

One dimension of corruption that Gabon has been relatively effective at curtailing is illegal logging. With 85 percent of its land area covered in tropical rainforest, Gabon is a part of the Congo Basin often referred to as the world’s second green lung after the Amazon. As a result, environmental governance policies by Gabon have regional and international implications. Known as a “green superpower” for its pioneering conservation and sustainable logging policies, Gabon is one of the world’s few net absorbers of carbon, potentially holding lessons for other countries seeking to protect their carbon-rich and ecologically valuable land areas.

While the 63-year-old Ali Bongo has largely recovered from a stroke he suffered in 2018, he has appointed Noureddine Bongo as his campaign manager. This is fueling speculation that the President is laying the groundwork for the perpetuation of the Bongo dynasty.

Liberia

Liberia

Presidential and Legislative, October 10

Liberia’s 2023 elections are shaping up to be a major turning point for whether the country continues its progress toward democratic consolidation—and with it prospects for greater stability and economic opportunity—or slides back toward the exploitative governance model and impunity of previous decades.

Liberians remain traumatized from the predatory governance practices of the military coup that brought Samuel Doe and subsequently Charles Taylor to power. It was their abuses of power that triggered and perpetuated the catastrophic civil wars from 1989 to 2003, resulting in the deaths of 250,000 people out of a population of 5 million.

Recognizing the disastrous consequences of wantonly corrupt and unaccountable executive power, Liberians emerging from the war were determined to establish a system of checks and balances. This included an independent legislature and judiciary, as well as an autonomous National Elections Commission (NEC), Liberia Anti-Corruption Commission, Central Bank, Public Procurement and Concessions Commission, and a small but professional military, among other bodies. Many of these institutions were launched and facilitated, if not consolidated, under the presidency of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

“[2018’s] peaceful transfer of power was a testament to the progress Liberia had made in building and upholding norms of limiting executive power.”

Johnson-Sirleaf stepped down after her constitutionally limited second term in January 2018. The peaceful transfer of power to a democratically-elected successor from a rival political party was a testament to the progress Liberia had made in building and upholding norms of limiting executive power.

Upon taking the mantle of the presidency, however, 1995 FIFA World Player of the Year, George Weah, has seemed intent on undoing the very guardrails against the abuse of power that have been a centerpiece of Liberia’s recovery.

In October 2020, four auditors probing the misappropriation of $25 million in Central Bank funds died under mysterious circumstances within days of one another. The government attributed the deaths to random accidents and suicide—accounts that most Liberians find unsatisfying. These deaths as well regular attacks by law enforcement officials on journalists, such as an incident where investigative journalist Zenu Koboi Miller was fatally beaten by Weah’s presidential bodyguards, send a chilling message to others attempting to report on or sustain norms of accountability.

The Weah administration has quadrupled funding for “public order and safety” to $48 million, doubled the budget for the National Security Agency to $11 million, and allocated an addition $10 million for “civil defense.” Yet, none of these funds are subject to audit and, therefore, neither to assessment as to how they are contributing to security.

A Liberian voter casts her ballot in 2020 during a constitutional referendum. (Photo: Emmanuel Tobey / AFP)

The U.S. State Department and senior White House officials have repeatedly criticized the corruption and human rights record of the Weah administration, including violence against journalists and arbitrary killings by the police. The U.S. Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control levied sanctions on three senior officials of the Weah administration in August 2022, stating that, “Through their corruption these officials have undermined democracy in Liberia for their own personal benefit.”

The World Bank and the ambassadors of nine governments have also called out the government for the misuse of donor funds.

Meanwhile, warlords from the civil war era have become more visible within the Weah administration. Prince Johnson gave an early endorsement to Weah. Another, Augustine Nagbe, has claimed that he was setting up a private militia to protect Weah.

Even Charles Taylor continues to command influence from his high-security prison cell in the United Kingdom, despite having been convicted of war crimes in the Hague. His ex-wife, Jewel Howard-Taylor, is Weah’s Vice President. She is also a leader of the National Patriotic Party, the political arm of Taylor’s armed front.

A young Liberian woman outside a voter registration center. (Photo: USAID)

An often overlooked legacy of the civil war is the large number of disadvantaged youth, some of whom are former child soldiers, who struggle with homelessness, violence, and drug addiction. Sometimes part of urban street gangs, these so-called “zogos” are linked to a growing problem of narcotics addiction and a rise in violence in the lead up to the election. In one incident in January 2022, 29 worshippers died in a stampede sparked by a gang of youth attempting a robbery.

In response to growing economic hardships in a country where half the population lives below the poverty line, there are periodic protests in Monrovia. These have been driven by spikes in food and fuel prices caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Liberians also face diminished purchasing power as the Liberian dollar has steadily weakened.

Meanwhile, Weah has been criticized for failing to disclose his assets (as required by law) or explain the source of funding for his construction of luxury apartments and acquisition of a private jet and yacht.

Several credible opposition candidates have put forward their nominations to challenge Weah in the 2023 elections. These include Joseph Boakai, a former vice president in Johnson-Sirleaf’s administration, who challenged Weah in the 2018 elections. He is the standard bearer of the Unity Party. Alexander Cummings of the Alternative National Congress, Tiawan Gongloe of the Liberian People’s Party, and Benoni Urey of the All Liberian Party have also thrown their hats into the ring.

Opposition parties loosely coordinate under a unity coalition, the Collaborating Political Parties (CPP). Collectively, the parties hold 13 seats in Liberia’s 30-seat Senate, compared to Weah’s Coalition for Democratic Change (CDC) party’s 5 seats. However, jockeying over positions, especially which of the party leaders would be put forward as the CPP presidential candidate, has thus far prevented the CPP from offering a united front. Given Weah’s status as a national sports hero, a disjointed opposition may enable Weah to come away with an absolute majority in the first round of Liberia’s two-round electoral system. The degree to which the opposition can form a unified coalition, therefore, will be an important storyline to the election.

“Beyond the personalities involved, the central issue to watch in Liberia’s 2023 elections will be how well the country’s nascent democratic institutions hold up against pressure to accommodate and reinstitute a strongman model of executive power.”

Beyond the personalities involved, the central issue to watch in Liberia’s 2023 elections will be how well the country’s nascent democratic institutions hold up against pressure to accommodate and reinstitute a strongman model of executive power.

One of the institutions most on the frontline is the NEC. In a referendum in December 2020, Weah had proposed eight amendments to the Constitution, including one shortening presidential terms from 6 years to 5 years. Fearing that Weah was using the amendment as a pretext for resetting the constitutional clock (thereby allowing him to hold office for two 6-year terms and then two 5-year terms), the public soundly defeated all eight resolutions. In so doing, they sent a clear signal that Liberians do not want to see a return of the imperial presidency of a bygone era.

NEC’s independence was on display in the successfully executed referendum, a by-election the same month in which opposition parties took 11 of the 15 contested Senate seats, and a special by-election in Lofa County in January 2022 that saw Weah’s CDC party win a razor-thin contest.

A voting station in Liberia. (Photo: UNDP)

NEC Chairperson Davidetta Browne Lansanah has been widely applauded for her capacity and integrity. Nonetheless, she has been the target of criticism from the Weah administration including what appear to be politically-motivated allegations of corruption and money laundering, charges she has denied. Monitoring the ongoing independence of the NEC, therefore, will be a key election story to watch.

The potential mobilization of security forces for domestic political ends also warrants attention. In the lead up to the 2020 by-elections, the Weah administration is alleged to have tried to create its own political party militia as a tool of intimidation. However, a commander of the police academy foiled the plan by refusing to accept the 150 party cadres sent to him for training.

Liberia’s 2023 presidential election, in short, will be a test of the country’s still fragile democratic institutions.

Madagascar

Madagascar

Presidential, November 16

The Madagascar 2023 presidential election is a reminder that democracy is far more than just holding elections. The relevance of this election cycle, therefore, can be best understood within the context of the country’s hollowed-out democratic institutions.

The island nation’s 30 million citizens are handicapped with a political system that has concentrated power in the executive branch, overriding the checks and balances that enable a government to be responsive to the priorities of its citizens. This creates a perpetual disconnect between Madagascar’s political leaders and the momentous challenges the country faces—increasing and intensifying climate-related disasters, corruption, and poverty.

“The Madagascar 2023 presidential election is a reminder that democracy is far more than just holding elections.”

This disengagement is seen by Madagascar being ranked in the bottom quartile of Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index and its low annual per capita income levels ($442), which have declined over the past 15 years. Madagascar has a 75-percent poverty rate, with 40 percent of the population below the age of 14.

Strengthening the mechanisms of popular participation, power sharing, and accountability enabled by institutions like an independent legislature, judiciary, and media will be the real priority of Madagascar’s democratic development, regardless of which candidate emerges victorious from this year’s election.

Residents try to resume their daily life following the passage of cyclone Cheneso in January 2023. (Photo: Elie Sergio / AFP)

Having won the second round of the presidential election in 2018, 48-year-old President Andry Rajoelina is vying for his second consecutive 5-year term in office. A former mayor of Antananarivo, Rajoelina first came to power in a military coup in 2009, displacing the democratically elected government of Marc Ravalomanana. Rajoelina stepped down in 2014 as part of a negotiated post-coup transition before running in 2018.

Rajoelina will be competing against Ravalomanana and Hery Rajaonarimampianina, Madagascar’s President from 2014 to 2018. The two opposition figures are expected to form a united platform in the effort to improve their prospects of defeating Rajoelina. The extent to which they can mount a coordinated campaign will determine how seriously they can challenge the incumbent.

“Strengthening the mechanisms of popular participation, power sharing, and accountability … will be the real priority of Madagascar’s democratic development.”

Opposition parties start at a disadvantage in that they require permits to hold demonstrations, which the government rarely approves. Institutionally, such barriers to political party organization create further detachment between the public and their political representatives.

Madagascar’s weak private sector means that government spending comprises a relatively significant share of the economy. Lacking adequate oversight mechanisms, political power becomes a means of personal self-enrichment. An estimated 90 percent of service contracts must be “validated” by the president and the prime minister. These dynamics create ongoing incentives for incumbents to stay in office.

Politicians’ financial self-interests also contribute to the limited political will to strengthen mechanisms of accountability. While in office, Rajoelina was able to push through a constitutional amendment that reduced the number of Senate seats from 63 to 18. Six of these seats are appointed by the president. The others are selected by an electoral college rather than being popularly elected.

This change represents a step backward in building a democratic connection between citizens and their leaders. It also weakens the ability of the legislature to act as a check on the executive. Since opposition members boycotted the Senate elections in protest of the move, the upper body is now nearly entirely dominated by Rajoelina’s alliance. Rajaonarimampianina’s party had controlled the majority previously.

The concentration of power within the executive inhibits the independence of other theoretically impartial institutions. Members of Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI), for example, are selected by the president. The executive also controls the electoral body’s budget, which is often underfunded. CENI’s independence and capacity, therefore, are constrained.

Andry Rajoelina during the presidential inauguration ceremony in 2019. (Photo: Rijasolo / AFP)

The Independent Anti-Corruption Bureau (BIANCO) conducts infrequent corruption investigations and pursues few prosecutions to redress corruption. While BIANCO has identified 79 lawmakers who have accepted bribes, the agency has not pursued cases against them, fostering a culture of impunity.

The executive branch also influences judicial decisions, and trial outcomes are frequently predetermined. This contributes to a lack of trust in the judicial system. The High Constitutional Court has demonstrated some independence from the executive in certain rulings, however.

While Madagascar ostensibly has a free press, criminal libel laws lead to self-censorship. This is especially so with regard to investigative reporting on sensitive issues like corruption. Therefore, a key feedback loop by which the public is informed and can hold the government accountable is weakened.

Madagascar’s security services (military, police, and gendarmerie) are subject to politicization, most visibly observed in the 2009 coup. Meanwhile, the security services provide limited protection to citizens from threats such as armed criminal groups or bandits (dahalo) operating in the south who target cattle and other household assets.

“Russia was brazenly involved in trying to fix the outcome of the 2018 election through disinformation, paying journalists to write flattering stories, and hiring young people to attend rallies.”

Madagascar’s weak governance oversight mechanisms and rich natural resources also make the country an attractive target for state capture by external actors. Russia was brazenly involved in trying to fix the outcome of the 2018 election through disinformation, paying journalists to write flattering stories, and hiring young people to attend rallies. Russia initially supported incumbent President Rajaonarimampianina’s bid for a second term. However, when this failed to gain traction, the Russians threw their support behind Rajoelina. Russia later struck a deal for a chromium operation of which it now has a 70-percent stake.

Given the permissive environment and negligible reputational or financial costs, further Russian electoral interference can be expected in 2023. With it comes diminished popular sovereignty—as well as a further barrier to responsive government.

With more than 80 percent of Madagascar’s flora and fauna being unique to the island, governance decisions in Madagascar have regional and international implications for global efforts to protect biodiversity and combat climate change.

There is much to watch in Madagascar’s 2023 election. Yet, most of what is genuinely important lies beneath the surface of conventional electioneering—and will require sustained attention long after the election is over, regardless of the victor.

Egypt

Egypt

Presidential, December 10–12

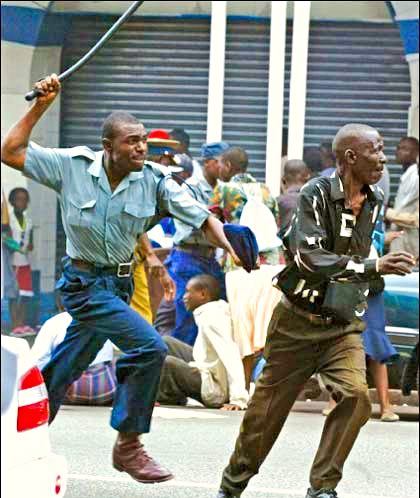

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi is expected to retain the presidency for a third term following perfunctory electoral proceedings scheduled for December 10-12.

Sisi faces only token opposition as his most prominent challenger, Ahmed al-Tantawi, a former parliamentarian with 2 million followers on Facebook, was repeatedly blocked from registering his candidacy with the National Elections Authority. Tantawi was prohibited from holding campaign events and security forces harassed and arrested his supporters, even for such seemingly trivial offenses as liking Tantawi campaign social media posts.

The current elections were moved up reportedly to shorten the election season and preempt mounting discontent.

Three lesser-known candidates will contest the elections, Hazem Omar of the People’s Republican Party, Abdel Sanad Yamama of the Wafd Party, and Farid Zahran of the Egyptian Social Democratic Party. However, a coalition of opposition groups are planning to boycott the elections to protest the blatant unfairness of the process.

The controlled electoral environment builds on a systematic pattern of the Sisi regime restricting political space in Egypt. An estimated 60,000 Egyptians—including many journalists, opposition party members, and human rights leaders—have been imprisoned under sweeping anti-terrorism laws.

Sisi first came to power in a coup against Egypt’s first freely elected president, Mohamed Morsi, in 2013. Formerly chief of the Egyptian Armed Forces, Sisi was appointed Minister of Defense by Morsi in 2012.

The incumbent was deemed to secure 97 percent of the vote during elections in 2014 and 2018. The latter was to be Sisi’s second and final term. However, a controversial constitutional amendment in 2019—put forward just 72 hours after it passed through parliament—extended his second term by 2 years and rescinded Egypt’s two-term limit provision, which had been established during the window of Arab Spring reforms. The amendment also extended presidential terms to 6 years, meaning Sisi could remain in power at least until 2030. Finally, the amendment allows Sisi to appoint the judiciary and a third of all senators.

Sisi is thus emblematic of the pattern of African military leaders who seize power through extraconstitutional means, then subsequently evade constitutionally instituted term limits to extend their time in power indefinitely.

Spontaneous protests regularly break out to condemn the deteriorating economic conditions and shrinking political space in Egypt. (Photo: Alisdare Hickson)

The current elections were originally planned for the Spring of 2024 but were moved up to December 2023, reportedly to shorten the election season and preempt mounting discontent stemming from Egypt’s economic spiral.

The Egyptian pound has lost 50 percent of its value since March 2022 and 75 percent since Sisi came to power. Inflation is running above 30 percent, and food prices have spiked by 72 percent over the past year. Egypt has been hard hit by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as the country relies on Russia and Ukraine for more than 80 percent of its grain supply.

Profligate spending under Sisi has caused Egypt’s sovereign debt to balloon to 95 percent of GDP, much of which is owed to external creditors such as Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. The deep reliance on external borrowers raises concerns among many Egyptians over the country’s compromised sovereignty.

Sisi is emblematic of the pattern of African military leaders who seize power through extraconstitutional means, then subsequently evade constitutionally instituted term limits.

Analysts attribute the monetary and debt crises to government economic mismanagement and expensive vanity infrastructure projects that have dubious economic justification. This includes the construction of a new administrative capital in the desert, a “summer capital” on the north coast, and a $28 billion Russian-financed-and-built nuclear power project in El Dabaa. The Egyptian military has resisted giving up control of significant segments of the economy, which has crowded out private firms and economic dynamism.

The series of structural economic challenges facing Egypt with limited recourse for political remediation suggest the country will face escalating economic and political unrest long after the December elections. Illustratively, after one spontaneous protest was broken up, the crowd began shouting the slogan of Egypt’s Arab Spring revolution, “The people want the fall of the regime.”

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Presidential and Legislative, December 20

The 2023 election in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) marks another important inflection point in this country’s long and elusive quest for democracy. To make progress, this country of more than 100 million people must overcome its deep-seated legacies of fraudulent, patronage-based, and opaque electoral practices institutionalized over the decades by the regimes of Mobutu Sese Seko and Laurent and Joseph Kabila.

The incumbent, President Felix Tshisekedi, is seeking a second 5-year term. Son of the esteemed democracy champion, Etienne Tshisekedi, Felix Tshisekedi had an ignoble start to his presidency. In the view of many, he cut a power-sharing deal with the outgoing president, Joseph Kabila, to be declared the victor of the December 2018 elections. Independent analysts, including the respected election monitoring group, the National Episcopal Conference of Congo (CENCO), indicated that the genuine winner by a commanding margin was the leading opposition candidate, Martin Fayulu.

Representatives of the National Episcopal Conference of Congo (Conference Episcopale Nationale du Congo – CENCO) speaking to journalists. (Photo: Junior D. Kannah / AFP)

Bowing to pressure from Kabila, the African Union and international democratic actors declined to demand a recount as called for by CENCO and many governments. A challenge of Tshisekedi’s first term, thus, has been to overcome weak legitimacy in the eyes of his compatriots.

Once in office, Tshisekedi has been able to claw away some influence from Kabila’s entrenched grip on the institutions of power. This includes replacing the Kabila-backed speaker of the National Assembly as well as the influential prime minister. Tshisekedi has also made some progress on reforms. Perhaps most notable has been his reducing the repressiveness of the security services by replacing certain senior intelligence and internal security officials who had been sanctioned for human rights violations. Tshisekedi has also made headway in replacing some Kabila loyalists within senior ranks of the judiciary.

This progress is noteworthy in that, upon stepping down, Kabila continued to exert great influence over the machinery of government in the DRC. Kabila’s Common Front for Congo (FCC) alliance controlled 350 of the 500 seats in the National Assembly as well as a majority of ministries, judicial appointments, and senior officials throughout the security sector. Many observers expected Tshisekedi to be little more than a front man for Kabila’s continued wielding of power behind the scenes.

Tshisekedi was also a prominent defender of democratic norms on the continent during his 1-year tenure as African Union Chairman in 2021-2022.

Nonetheless, in the process of winning over Kabila allies in government, democracy activists worry that Tshisekedi has adopted some of same tactics as his predecessor. This includes the reliance on patronage to direct the unwieldy bureaucracy of the Congolese state.

Finance Minister Nicolas Kazadi noted, for example, that the budget for exceptional security expenses had increased tenfold, though with little transparency over how these resources were improving security given the country’s notoriously corrupt and abusive security sector.

Tshisekedi and his family have been linked to opaque deals with Chinese businesses for access to artisanal copper, cobalt, and diamonds. Tshisekedi has also been criticized for not doing enough to rein in the mechanisms of state capture employed by Kabila. This includes a $6-billion infrastructure-for-resources swap with Chinese state-owned firms dubbed the “deal of the century” and the embezzlement of $3.7 billion in state funds by internationally sanctioned mining magnate, Dan Gertler, through Kabila-endorsed contracts.

Tshisekedi controversially appointed close ally Denis Kadima as the new commissioner of the Independent National Election Commission (CENI) in 2021. Tshisekedi also modified the allocation of seats within CENI. While opposition parties and civil society are represented, critics feel the distribution still favors the ruling party.

Martin Fayulu (left) and Felix Tshisekedi (right) at a press conference in 2018. (Photo: Fabrice Coffrini / AFP)

Many democracy advocates, moreover, are critical that the Tshisekedi-led National Assembly failed to pass an amendment that would require CENI to adopt electoral best practices such as announcing electoral results at each polling center. Tallying and reporting of aggregate results from a central location is less transparent and more prone to rigging. In Kenya, for example, results announced at polling stations are final and cannot be altered. Additionally, the DRC relies on candidates gaining a plurality of votes rather than an absolute majority, making it easier for a candidate to win by solely appealing to their base rather than building a more inclusive coalition.

Tshisekedi faces credible opposition from numerous quarters. Most prominent among these is Martin Fayulu, the former ExxonMobil executive widely perceived to have won the 2018 election. Born in Kinshasa, Fayulu commands a broad following across the DRC’s highly diverse constituencies. Moïse Katumbi, a former governor from the southeastern region of Katanga, is another popular rival. He was seen as such a threat by Kabila that the former leader launched several gratuitous court cases against him, forcing Katumbi into exile. Former Kabila Prime Minister Augustin Matata Ponyo Mapon is another prominent entrant to the presidential race. In 2018, there were nearly two dozen presidential contenders. The presence of so many candidates introduces considerable unpredictability given the DRC’s single-round plurality system.

While the DRC’s electoral institutions and oversight mechanisms may be weak, the country has a vibrant and organized civil society committed to a democratic system of government. These groups continue to demand transparency and popular participation in elections and holding leaders accountable to citizen interests. Among the most prominent, CENCO deployed over 40,000 election monitors in 2018. Through the experience gained from multiple cycles of parallel vote counting processes, it is increasingly difficult for candidates to credibly claim outcomes that deviate significantly from independent tallies.

“While the DRC’s electoral institutions and oversight mechanisms may be weak, the country has a vibrant and organized civil society committed to a democratic system of government.”

Another wild card in the 2023 election is the ongoing instability in the east of the country. This is a multilayered conflict involving rivalries between Rwanda and Uganda, access to and trafficking of the DRC’s vast and unregulated mineral deposits, 140 local armed groups, ethnic rivalries, and legacies of previous conflicts in the Great Lakes region. Prospects of Chinese and Russian interests joining the competition for resources in the region adds another level of complexity. Perceptions that Tshisekedi may have made opaque deals for DRC’s resources also sets off a strong nationalist resentment that may have political consequences.

The resurgence of the threat from the armed group M23 in late 2021 has heightened tensions among all parties and added to the displacement of more than 5.5 million people from Ituri, North and South Kivu, and Tanganyika Provinces. The deployment of the East African Standby Force at the end of 2022 has helped tamp down tensions, though this will need to be translated into longer-term mediated solutions.

Ongoing instability may affect the ability of these eastern provinces to vote—an issue also faced in 2018. A full-blown regional conflict would clearly scramble the entire electoral process. Tshisekedi advisors have suggested that the elections may need to be delayed due to the unrest. This is fueling concerns that the instability in the east may be used as a pretext for Tshisekedi to prolong his tenure—harkening back to Kabila’s 2-year delay before holding elections after his second term had expired.

Students work on laptops during an election transparency hackathon event in Kinshasa on August 10, 2022. (Photo: Andrew Harnik / AFP)

The 2023 elections will say much about the trajectory of the Tshisekedi presidency. Will it hold to his stated democratic and reformist aspirations? Or will it fall into the well-worn governance norms in DRC—building exclusive patronage networks at the expense of public goods and services?

With so many uncertainties, the DRC polls may be the most unpredictable on the continent in 2023. While the DRC does not have a strong track record of transparent and credible elections, this remains the aspiration of millions of Congolese citizens. Experience has also shown that civil society will not blithely accept a fabricated outcome. Much may once again come down to the courts—and how regional and international actors respond.