The date was January 20, 1964. In an event that shocked the young nation, soldiers of the Tanganyika Rifles mutinied over pay, promotions, poor living conditions, and the slow pace of Africanization of the armed forces. It started in Colito Barracks in the capital Dar es Salaam, but quickly spread to Tabora in central Tanzania and Nachingweya in the south. It was then that founding president, Julius Nyerere, realized that his country’s future stability depended on the strategic decisions that he would make that morning. “While realizing the gravity of the situation … we also had to be farsighted. We ultimately applied the law, but we did not take retribution,” wrote Nyerere in his memoir. “Every cloud has a silver lining. … It enabled us to build an army almost from scratch. Many institutions we have inherited, but the army is something we built ourselves.”

Nyerere chose a path that balanced a firm response to the mutineers while avoiding humiliating the mutineers with retaliation. In doing so, Nyerere spared Tanzanians the cycle of revenge killings that afflicted other countries in similar situations. The late Tanzanian general Herman Lupogo noted that the stability created by rebuilding the army and integrating it into society survived Nyerere and was inherited by his successors. Such instances of strategic leadership are pivotal but often do not receive much attention, despite the fact that they offer practical lessons in leadership for the next generation of military and civilian leaders. Strategic leadership is a central theme of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies’ annual Senior Leaders Seminar, which this month is bringing together high-level military, government, and civilian representatives from 45 African countries.

* * *

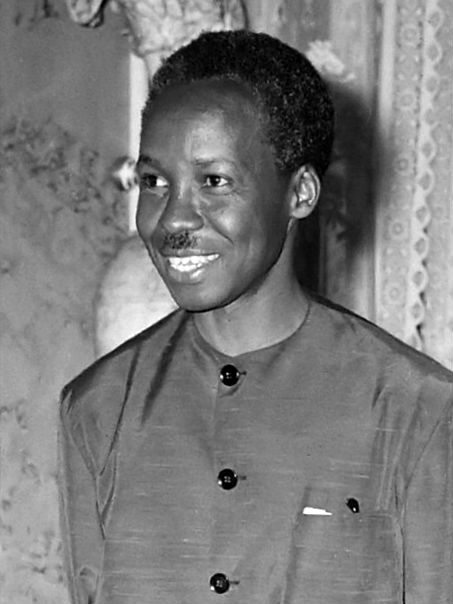

Mozambique’s Joaquim Chissano faced a different set of strategic leadership challenges than Nyerere but the decisions he took were no less fateful for his country. On October 19, 1986, the nation’s charismatic founding president, Samora Machel, died in a plane crash on his way home from a summit meeting in Zambia. He had been with leaders of southern African countries coordinating military action against apartheid South Africa. Machel’s presidential aircraft went down in mountainous terrain where the borders of Mozambique, South Africa, and Swaziland merge and was rumored to have somehow been caused by the South African Government.

Machel’s sudden death shocked Mozambique and threatened the young country’s stability. Much of the crash site was located inside South Africa, then an implacable enemy. At the same time, Renamo, a rebel group supported by the apartheid regime, had launched a major offensive against the government in Maputo. A few weeks before the crash, Machel had threatened to seal off his country’s borders with neighboring Malawi over its alleged support for Renamo, while South Africa threatened the Mozambican leader with retaliation for supplying anti-apartheid guerrillas, saying Machel “will clash, head on, with South Africa.”

This was the explosive situation into which Chissano, then foreign minister, was thrust. With the nation in mourning, the military organizing a massive counterattack against Renamo, and rumors of a planned strike into South Africa, the ruling Frelimo party elected him as Machel’s successor. Almost immediately he faced two stark choices: escalation or moderation. In 1988, he chose the latter by opening peace talks with Renamo.

Chissano’s decision was neither easy nor popular. Frelimo had been locked in a bitter war with Renamo since independence in 1975, inflicting massive damage on the country, killing hundreds of thousands of Mozambicans, and displacing millions. The rebels were regarded as bandits, notes scholar and former Frelimo government official, Irae Baptista Lundin, making the idea of negotiations unpopular. By opening the negotiations, Chissano, himself a celebrated guerrilla commander, faced internal resistance. Indeed as he prepared to take the reins, a fellow official remarked, “One individual is not going to change our policies, for those are collective decisions of the party.”

Change therefore came incrementally—under Chissano’s firm but persuasive and strategic leadership. His starting point, Baptista notes, was a recognition that all protagonists in the civil conflict shared a common Mozambican citizenship. Then in 1989, during Frelimo’s fifth congress, Chissano shifted his focus onto party hardliners, persuading them that the country’s best interests lay in engaging Renamo. In the process he stopped using the propaganda phrase “armed bandits” and began to refer to Renamo by name, an important rhetorical shift intended to signal his intention for a resolution to the conflict. Furthermore, Frelimo resolved to liberalize the political system, setting the stage for future multiparty elections—a decision that stunned observers.

Despite the continuing legacies of mutual distrust, these strategic decisions were central to creating the environment in which peace could be achieved. In 1992, the Rome General Peace Accords were finally signed, officially ending the civil war. Chissano championed the principles of moderation and compromise through the end of his presidency, when he voluntarily left office after completing two five-year terms, despite the constitution allowing him to run for a third term. This lesson in leadership was carried on by his successor, Armando Guebuza, who himself stepped down after two terms.

Lessons in strategic leadership

In both the Tanzania and Mozambique cases, the temptation for retribution against enemies was strong, and both Nyerere and Chissano commanded high levels of legitimacy that would have rationalized the pursuit of hardline policies. However, both had the foresight to predict the dangers of such a course—Nyerere by treating the mutiny as a political problem that required structural reform in the military and the political process, and Chissano by seeing peace as the only pathway to long-term stability.

Furthermore, both modeled leadership styles that promoted higher objectives. Nyerere modeled ethical leadership, captured in a code known as Ujamaa, or “self-reliant and service oriented leadership” which was adopted by the military and other institutions. Chissano modeled inclusive and reconciliatory leadership, a significant achievement given his background as a guerrilla leader and party doctrinaire, and one that earned him the credibility to later become an important mediator in several African conflicts. Above all, Chissano is credited for steering his country from the precipice after it lost its founding father and ending a brutal 16-year civil war.

Several principles can be gleaned from these notable examples of strategic leadership. First, leaders cannot sacrifice their country’s future well-being on the altar of political expediency. They must seek accommodation with enemies and have the moral courage to persuade reluctant followers, even at the risk of losing popularity. Next, strategic leaders hold themselves to high standards of moral and ethical conduct and in the end create an enabling environment for leadership succession.

Additional Resources

- Joaquim Chissano, “An Open Letter to Africa’s Leaders,” The Africa Report, January 14, 2014.

- Irae Baptista Lundin, “The Peace Process and the Reconstruction of Reconciliation Post Conflict: The Case of Mozambique,” Higher Institute of International Relations, February 28, 2004.

- Herman Lupogo, “Tanzania: Civil Military Relations and Political Stability,” African Security Review, Institute for Security Studies, Volume 10, No 1, 2001.

- Aleck Humphrey Cheponda, “Aspects of Nyerere’s Political Philosophy: A Study in the Dynamics of African Political Thought,” African Study Monographs, Volume 1, No. 3, 1984.

- Chimwemwe Salie Hara, “Africa’s Own leadership Lessons,” The Daily Nation, December 30, 2015.

- Dennis Onyango, “Former Mozambican President Joaquim Chissano: A Democrat and Global Peace Envoy,” Pan African Newswire, January 20, 2008.

More on: Leadership Mozambique Tanzania