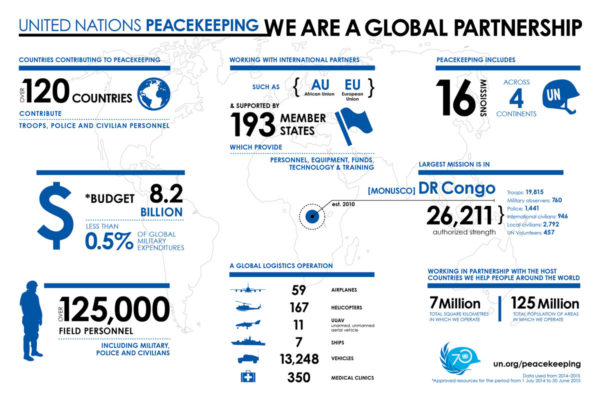

Over 100 countries provide more than 125,000 uniformed and deployed personnel supporting 16 ongoing UN peace operations. Seventy eight percent of these personnel currently serve on the African continent. More than half of these (over 60,000) represent 39 different African countries. The African Union has two ongoing missions involving approximately 28,000 troops: the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) and the African-led International Support Mission to the Central African Republic (MISCA).

Peacekeeping, in short, has become a key pillar in the security architecture for Africa.

Adapting peacekeeping to the challenges of the contemporary security environment was a key theme of the Leader’s Summit on Peacekeeping which was hosted by U.S. President Barack Obama on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly meetings. In support of the occasion, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies highlights some of the key challenges, evolving trends, and lessons learned from peacekeeping operations in Africa in recent years.

Evolution of the peace operations environment to peace enforcement and stabilization

The shift from traditional peacekeeping to peace enforcement and stabilization missions is one the major emerging trends in African security. It reflects the changing, and increasingly complex nature of the African security environment that now confronts a range of nonstate actors including insurgents, terrorist groups, and criminal networks.

Traditional UN peacekeeping guidelines were conceived to manage interstate wars and built on principles of consent, impartiality, and the limited use of force. Stabilization missions, on the other hand, are based on the premise that to achieve stability requires containing spoilers – actors that have vested interests in perpetuating instability. Recognizing the political objectives of these spoilers is one of the key findings highlighted by a High-Level Independent Panel that reviewed lessons from the past five decades of UN peacekeeping in a report submitted to the UN Secretary General in June, 2015.

Mvemba Dizolele, a Distinguished Stanford University Scholar, says that the shift towards peace enforcement is a positive one because Africa is now starting to take more responsibility for its security. He explains that peace enforcement missions such as those being conducted by AMISOM in Somalia have created a sense of ownership among African countries as well as greater appreciation about the importance of early responses to crises.

This, in turn, has created greater commitment to provide funding for such missions. “South Africa for instance spent over $100 million of its own money in Burundi for the African Mission to Burundi (AMIB) and for the Special Protection Detachment that it proactively deployed to provide security for returning Burundian exiles. These are funds it will never get back from the AU or UN,” notes Cedric de Coning, an Advisor to the African Union Peace Operations Support Division. Similarly Kenya is using its own Navy to resupply and support its contribution to AMISOM.

The shift towards peace enforcement has also led to a division of responsibility whereby the AU normally takes the lead in peace enforcement. Once a context is stabilized, these missions tend to fall under the UN umbrella as a more traditional peacekeeping operation in what some have described as “hybrid peacekeeping,” the new term for multidimensional peace operations.

A key concern with the peace enforcement approach is that the national interests of troop contributing countries will supersede the agenda of a peace operations mission. De Coning explains: “peace enforcement operations should not be misunderstood as seeking military solutions but rather seen as a larger strategy to proactively shape the security environment by containing the aggressors, in order to create space for the political, peacebuilding, and humanitarian actions to take root.” He suggests that a new UN stabilization doctrine is required that provides guidance on the kind of command and control, mission support and logistics, rules of engagement, equipment, and training that would be required when the UN is tasked with peace enforcement mandates in the future. “This would help protect the existing UN peacekeeping doctrine and identity from being misapplied in contexts where it is not fit for the purpose.”

Lessons on sustaining peacekeeping capacity

The greater reliance on peace operations in Africa compels more effective means to build and sustain peacekeeping capacity within Africa’s key troop contributing countries. The inability to retain crucial military skills required in the peacekeeping environment is a major gap. “The reality is that all military skills are inherently perishable and it is therefore inaccurate to reference a cumulative total of trained peacekeepers,” explains Daniel Hampton. “Trained soldiers show marked degradation of task retention after just 60 days. Without practice or retraining, proficiency continues to erode to the point that after 180 days there is an estimated 60 percent loss of skills.”

To solve the problem international and African partners must move away from the standard assistance package of “train and equip” to a new model of peacekeeping assistance that focuses on building and supporting indigenous institutions, Hampton suggests. In this new model, “peacekeeping tactics, techniques and procedures are embedded in doctrine and reinforced throughout all levels of a professional military education (PME) system.” Furthermore, “lessons learned and operational experience are incorporated into curricula and training. The real metric of success is not how many personnel receive training, but rather how well a country sustains capability and operational readiness with a capacity to respond to an AU or UN request,” he adds.

Such an approach requires African soldiers as trainers, explains Hampton: “The days of Western soldiers standing in front of African soldiers as primary instructors should be long gone. Several African militaries could be characterized as professional peacekeepers with little need for outside assistance, among them including Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, and South Africa, each of which has provided troop contingents to UN missions almost continuously for well over a decade.” He suggests that strengthening existing PME systems, establishing these where none exist, and incorporating peacekeeping training centers of excellence into a larger PME strategy are essential to these efforts.

The evolving nature of peace operation missions, similarly, requires a different set of skills and capabilities than past peacekeeping missions. Peacekeeping training needs to be more closely aligned with contemporary mission needs and mandates. This is a key finding of a report of lessons learned from 20 years of peacekeeping training experience by the African Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). The report calls for closer integration between applied research and training to design, update, and improve curricula to respond to the changing demands of the peacekeeping environment. It also stresses the importance of undertaking regular field visits to collect data directly from civilian and military peacekeepers so as to incorporate findings into curriculum development.

How should international partners assist in building capacity?

International assistance programs should be calibrated to building African capabilities in three areas according to Daniel Hampton:

- In the first phase—train the trainer—international subject matter experts are used as needed to train host-nation cadres

- In the second phase—train the peacekeepers—international trainers observe and mentor the African instructors with little interaction with trainees

- In the third phase—sustainment training—requires retention of a professional cadre of African defense force trainers that endure over time

International cooperation should also address the gap between the highly complex tasks that are increasingly being demanded of African peacekeepers and the force configurations and training required to perform them, adds Paul Williams. He explains that infantry battalions, which are the standard force designs used in traditional peacekeeping, are not well-suited for the sorts of missions required in situations where non-state actors such as terrorist organizations and insurgents have to be confronted. Furthermore, new skill sets such as countering improvised explosive devises and conducting reconnaissance and surveillance through the use of new technologies including unmanned aerial vehicles are required for peacekeepers to operate effectively in the increasingly asymmetric peacekeeping environment. International partners should do more to provide these niche capabilities.

Hampton sees a need for African states to start investing more in building peace operations capacity. “[African governments] must not allow themselves to become habitually dependent upon donor support to participate in UN or AU missions. It is in their interest to develop and sustain an indigenous capacity to generate trained and ready peacekeepers.” With regards to funding, Paul Williams explains that “the lack of indigenous sources of finance undermines the AU’s credibility as a leading player in peace and security issues on the continent.” While several funding facilities to support African peacekeeping are in place at the UN, European Union, and bilateral level, he contends that African countries need to do more to generate indigenous resources through the AU’s Peace Fund. Likewise, more consideration should be given to alternative resource generation strategies.

Africa Center Experts

- Daniel Hampton, Professor of Practice, Security Studies, Africa Center for Strategic Studies

Africa Center Research and Resources

- Daniel Hampton, “Creating Sustainable Peacekeeping Capacity in Africa,” Africa Security Brief, No 27, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 2014.

- Paul Williams, “Peace Operations in Africa: Lessons Learned Since 2000” ACSS Research Paper, No 25 Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2013.

- “Peacekeeping in Africa: A Conversation with Paul Williams” ACSS Video Interview, September 2015

Additional Resources

Africa’s security trends and future scenarios for peace support operations

- Linnéa Gelot et al, “Strategic Options for the Future of African Peace Operations: 2015 – 2025,” NUPI Report No 1, Norwegian Institute for International Affairs, February 2015.

- Cedric de Coning, “Enhancing the Efficiency of the African Standby Force: The Case for a Shift to a Just-in-Time Rapid Response Force,” African Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes, February 2014

- Emmanuel Kwesi Aning, “Africa: Confronting Complex Threats: Coping With Crises,” International Peace Academy, February 2007.

Lessons and best practices in African peacekeeping training

- Yvonne Kasumba, “The Limits and Opportunities of Peacekeeping Training and Education,” Journal of International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University, Vol 1, No1 2005

- African Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes, “20 Years of Training for Peace: Building Peace Support Operations Capacity in Africa,”, March 2015

- United Nations, “Uniting our Strengths for Peace, Politics and People: Report of the High Level Independent Panel on United Nations Peace Operations,” June, 6, 2015

Leveraging external assistance to build African peacekeeping capabilities

- Cedric de Coning, “The Significance of a Resilient AU-UN Strategic Partnership for Peace Operations in Africa”, Complexity for Peacebuilding Blog, February 15, 2015.

- Adam C. Smith, Paul D. Williams and Donald C.F, “Lessons Learned from Operational Partnerships in UN Peacekeeping,” International Relations and Security Network, September 3, 2015

- Paul Williams, “How Should the United States Increase its Support for AU Peacekeeping?” ACSS Video Interview, September 2015

African efforts to develop indigenous peacekeeping capacities

- Timothy Walker, Pakamathi Lisa, et al, “Building African Capacities for Peacekeeping” Seminar Report, Institute for Security Studies, March 2011

Some AU Recognized Peacekeeping Training Centers of Excellence in Africa:

- African Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), Durban, South Africa

- Institute for Security Studies (ISS), Pretoria, South Africa

- Kofi Anan International Peacekeeping Training Center (KAIPTC), Accra Ghana

- International Peace Support Training Center (IPSTC), Karen, Kenya

- Southern African Development Community (SADC) Peace Support Training Center, Harare, Zimbabwe

- Peacekeeping Training School, Bamako, Mali

- African Peace Support Trainers Association, Nairobi, Kenya

More on: Peacekeeping