Military professionalism is commonly grounded in several overriding principles: the subordination of the military to democratic civilian authority, allegiance to the state and a commitment to political neutrality, and an ethical institutional culture. These principles are enshrined in values that distinguish the actions of a professional soldier such as discipline, integrity, honor, commitment, service, sacrifice, and duty. Such values thrive in an organization with a purposeful mission, clear lines of authority, accountability, and protocol. Despite the disappointing track record, these same principles and values of professionalism resonate deeply with African military leaders and ordinary citizens alike. The problem has been that in too many African countries the adaptation and implementation of these concepts have been disrupted.

Democratic Sovereign Authority

A democratic political culture is typically the foundation of professional militaries. In Samuel E. Finer’s classic The Man on Horseback: The Role of the Military in Politics, the level of democratic political culture in a country is determined by the extent to which there exists broad approval within society for the procedures of succession of political power and a recognition that citizens represent the ultimate sovereign authority.5 Democratic processes also need to be protected by state institutions, such as the armed forces. The notion of military professionalism in democratic states, therefore, must embody basic values such as acceptance of the legitimacy of democratic institutions, nonpartisanship in the political process, and respect for and defense of individuals’ human rights. In a strong democratic political culture, legitimately elected civilian authorities are fully responsible for managing public and political affairs. The armed forces implement the defense and security policy developed by civilian authorities.

A majority of African states have duly adopted these democratic values and basic principles of military professionalism in their various constitutions and military doctrines. They are shared and accepted by the majority of African countries that have transitioned or are in the process of transitioning to a democracy. Moreover, many military leaders have been exposed to these values and principles through trainings in Western military academies and staff colleges. It is important, too, to note that these values are rooted in African culture. Protection of the kingdom, submission to the king, loyalty, and integrity vis-à-vis the community were core values of African ancestral warriors. It was only during the colonial and neo-colonial eras that this civil-military relationship foundered and these values eroded. The newly created African states set up armies to symbolize their nations’ independence, but these militaries essentially provided security just to the new regimes. Since then, we have witnessed an ongoing struggle to recapture the historical values of military professionalism.

Allegiance

Building professional militaries is dependent upon establishing a clear and balanced allegiance to the state and respect for civil society and not interfering in the oftentimes robust political discussion between the two. Democratization is a turbulent process, one that can be exploited by certain actors to create temporary domestic instability. Without a military’s steadfast support for neutrality and democratic sovereign authority, the process of democratic self-correction and consolidation will be difficult.6

One African military that has adhered to this principle is the Senegalese Armed Forces. Since independence, Senegal has never experienced a coup d’état. The Senegalese democratic culture has been periodically tested by political tensions, but the military has not challenged the constitutional order. Having passed these tests, Senegal’s democratic culture has grown stronger over the years.

In addition to Senegal, Botswana, Cabo Verde, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia, and a few others are part of a small group of African countries whose governments have never been toppled by a military coup.7

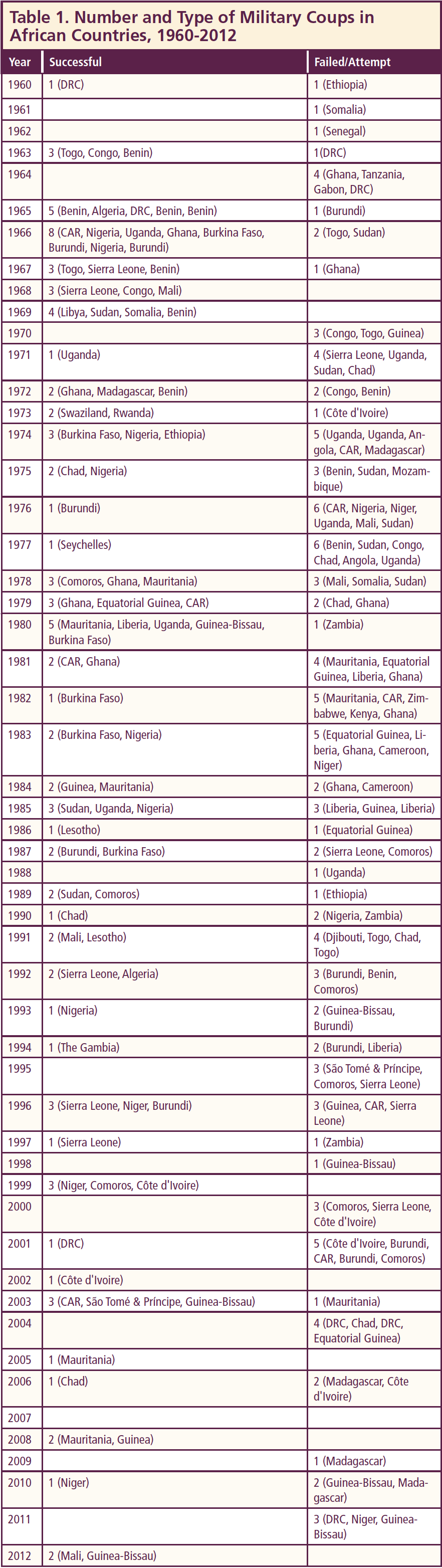

Countries that have experienced a coup d’état pay a steep and longterm price for their militaries’ misplaced and sometimes cyclical interference in political discourse. Once the precedent of a coup has been established, the probability of subsequent coups rises dramatically. In fact, while 65 percent of Sub-Saharan countries have experienced a coup, 42 percent have experienced multiple coups.8 Most African coups were directed against an existing military regime that itself had come to power through a coup. Between 1960 and 2012, 9 of the attempted coups in Sudan were against military regimes as were 7 of the 10 in Ghana during the same time period. Once in place, such precedents become a burden that is difficult to throw off and have contributed to the collapse or destabilization of some states. Reflecting a degree of progress, while the threat of coups remains a real concern in Africa, the frequency of successful coups has diminished considerably (and has been concentrated in West and Central Africa) since the mid-2000s compared to previous decades (see Table 1).

Source: Barka and Ncube, September 2012.9

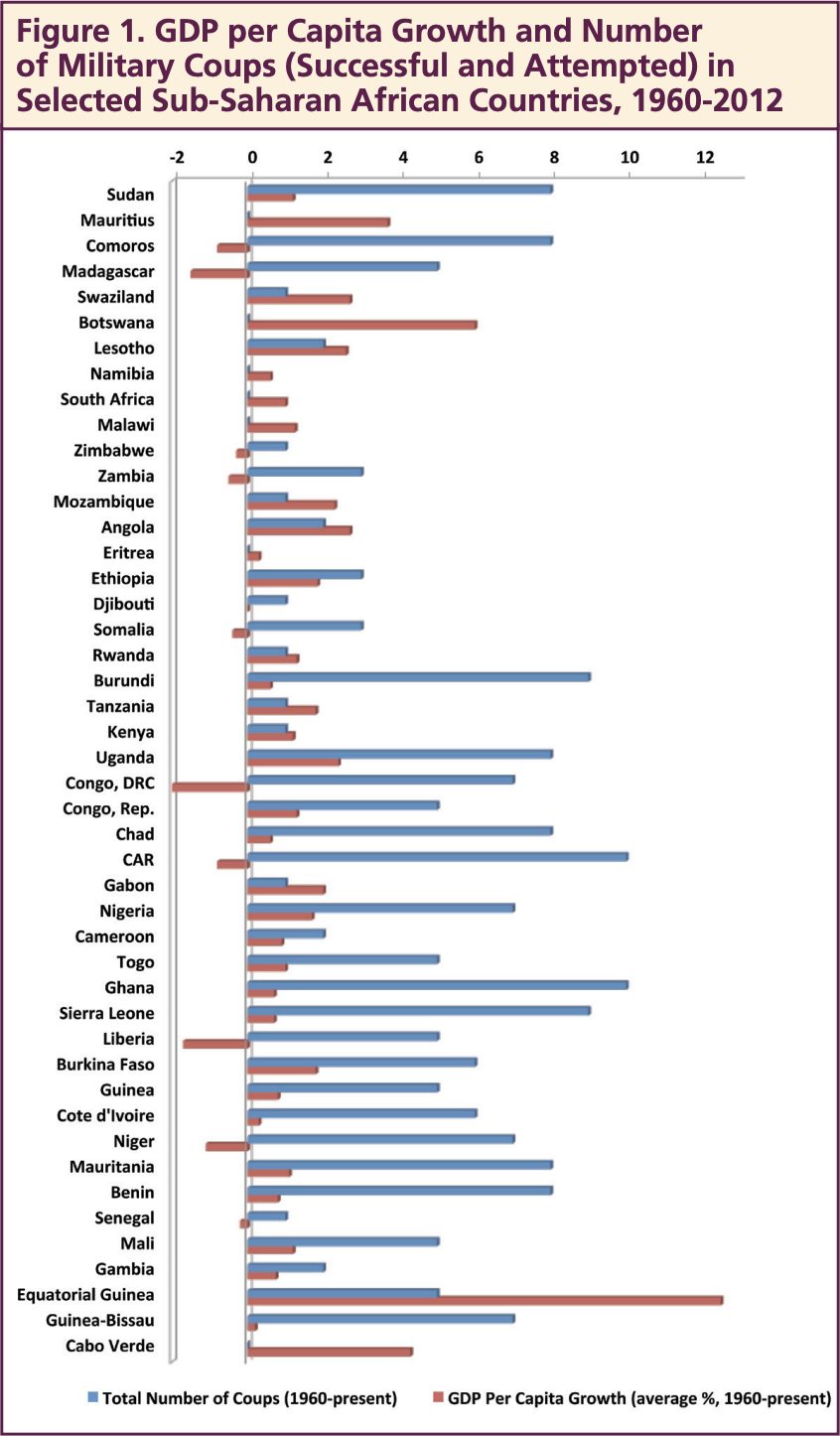

Factors such as political and economic weakness, corruption, and a lack of institutionalized democratic structures create openings for military forces to justify overthrowing political leaders. Unsurprisingly, Sub-Saharan countries with low per capita gross domestic product (GDP) growth since independence have experienced more military coups than countries with higher per capita GDP growth rates.10 Yet, with very few exceptions, military coup leaders fail to restore stability and hand power back to civilians. Unfortunately, military-led governance is likely to be ruinous for a country’s economy. Thus, the vicious cycle is perpetuated. Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, and Nigeria have all seen their real GDP shrink more than 4.5 percent following military coups.11 Figure 1 highlights the negative correlation between multiple coups and a country’s long-term per capita GDP growth. Repeated coups have thrown some African countries, such as Burundi, the Central African Republic, Comoros, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Guinea-Bissau, into prolonged periods of economic contraction. Apparent exceptions like Equatorial Guinea, in fact, reflect natural resource-driven growth that has not translated into improved living conditions for the general population. Instability deters investment and development. In contrast, non-resource-rich states that have realized the highest levels of sustained growth are almost uniformly those with few or no coups.

Source: Barka and Ncube, September 2012.12

Samuel Huntington argued that military interference in governmental affairs was more a political than a military problem, an observation that remains particularly relevant for most African countries.13 In the absence of well-established rules and strong institutions regulating political processes, labor unions, students, clergy, lobbies, and the military all engage in political competition for the control of state power. This characterized the post-independence political environment in many African countries. Given their size and inherent influence, militaries in Africa thus became major players on the political scene—and held onto this privilege.

With the emergence of alliances between top military, political, and economic leaders (including, at times, foreign partners) around shared financial interests, militaries’ intrusion into the economic sphere also became more diffuse and complex. In Angola, for example, members of the military participate in contract negotiations with foreign companies, sit on corporate boards, and are majority shareholders of telecom companies.14 The various military administrations that governed Nigeria also entangled themselves in the economic sphere. Appointments of military officers to company boards of directors and to top political posts, such as state governors, made these individuals immensely rich and politically powerful. Even in retirement, many of these officers remain powerful actors in Nigerian politics.

In 1999, when the Nigerian people elected the democratic government of Olusegun Obasanjo, a retired general, they ended 16 years of military rule. The new government understood what years of military involvement in commercial enterprise had done to its reputation and effectiveness. The government quickly swept many officers into retirement, revoked oil licenses, and reclaimed plots of land suspected to have been illegitimately allocated to senior military officers.15 Such efforts to improve security sector governance in Nigeria are ongoing.

The subversion of the profession of arms for financial enrichment distorts the incentives for public service required of an effective, professional military. It simultaneously undermines a military’s commitment to protect the country and its citizens. Plato noted some 2,400 years ago that the meddling of soldiers into other professions will “bring the city to ruin.”16

Egypt’s Complex Civil-Military Relations

“Egypt’s second republic will only come to life when the officers’ republic ceases to exist.”17 This somber warning reflects decades of complicated civil-military relations in Egypt. Egypt became a nominal republic in 1952 when the military deposed King Farouk. The country’s first president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, was a former military officer. So were successive leaders, Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak, amassing 59 years of de facto military governance. The military was effectively the power behind the power in Egypt, intimately involved in policymaking and maintaining the status of the incumbent. The military took over state-owned enterprises,18 controlling many economic ventures—from running daycare centers and beach resorts to managing gas stations. And it reported none of this income to the government.19

The events of the Arab Spring in 2011 precipitated a break in this pattern. The massive scale of the protests led the military to conclude that stability of the state was threatened, and it orchestrated the arrest and deposal of Hosni Mubarak in February of that year. The military earned widespread plaudits from Egyptians and the international community during this time for the restraint it demonstrated in not responding with violence against the largely peaceful demonstrations. The military effectively took control of the government at that point, ruling under the auspices of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF).

Facing a spiraling economy and numerous domestic and international pressures for change, the SCAF organized a hasty process for drafting a new constitution and a timetable for parliamentary and presidential elections. Parliamentary elections were held in late 2011 with the Peace and Justice party, representing the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood, emerging as the dominant political actor.

Eager to protect the military’s many political and economic privileges from a new head of state, the SCAF issued a supplemental constitutional declaration just days before presidential elections in June 2012. In it, SCAF assumed control over all military affairs and gave itself a significant role in the committee charged with drafting the new constitution.

After Mohamed Morsi became Egypt’s first democratically elected leader, he purged the generals who had issued the constitutional addendum, but he was unable to roll back the powers and privileges the SCAF had bestowed upon itself. The military and the new civilian leaders appeared to have reached an uneasy governing arrangement with the military retreating from a public governance role and even acceding to the replacement of top generals by President Morsi.

The constitution that subsequently passed through referendum in December 2012 made the military’s autonomy official. It required that the minister of defense be a military officer. Parliament did not have oversight of the defense budget. Instead the budget was placed under the purview of the National Defence Council—a 15-member authority, 8 of whom were military20—leaving the public and government in the dark about how the military would spend its annual budget allocations and expenditures. It also meant that the military could continue to earn untold levels of revenue through its economic privileges. From television sets to olive oil, the military’s vast economic ventures pay no taxes, use soldiers as laborers, and buy public land on favorable terms.21

The exclusive governing style of President Morsi, his assertion of expansive and ill-defined powers, continuing economic turmoil, deepening divisiveness borne of fears that Islamists were seeking to dominate Egyptian society, and ongoing uncertainty over the legality of the 2012 constitution led to steadily growing tensions within Egyptian society. Massive protests in late June 2013 again created an opportunity for the military to intervene. On July 2, the military ousted the sitting president, again on the justification of maintaining national stability. In the subsequent protests by Morsi’s supporters the military opted to use force to disperse the protesters and arrest leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood. This crackdown claimed over 1,000 lives.

In the ensuing year, the military further expanded its control, arresting an estimated 20,000 people perceived as a threat to the military and clamping down on endent media and civil society.22 Through a new constitution passed by referendum in 2014, the military affirmed autonomy over its budget, immunity for its members from prosecution outside of a military court, and the power to arrest and try civilians in a military court. The military, moreover, not only reasserted but expanded its control of the economic sphere from basic items, such as bottled water and furniture, to larger infrastructure, energy, and technology projects.23 The military simultaneously paved the way for its commander, General Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, to run for and win one-sided presidential elections in 2014 (garnering 96 percent of the votes cast), formalizing his role as head of state.

While the military no doubt views these events as a return to the military’s rightful role as the dominant institution in Egyptian society, it is clear that the Egyptian military failed to uphold the principles of military professionalism: subordination to democratic civilian authority, allegiance to the rule of law, and an ethical institutional culture. As the events in Egypt reveal, when a military is unable to adhere to one of the pillars of professionalism, it finds itself in conflict with all three.

An Ethical Institutional Culture

In addition to democratic civilian control of the military and allegiance of the military to the nation, an ethical culture is a prerequisite for building a professional military. This entails values such as merit-based promotion, accountability of military leaders and soldiers for their actions, as well as demonstrating competent, impartial, and humane security enforcement. These institutional values do not come naturally. They must be taught. Soldiers must be inculcated with specific training in ethics, just as they learn discipline, law, and combat—all within the bigger picture of the military’s role in a democratic society.

A soldier’s ethos is an essential pillar of the institutional culture of the military and to the success of its mission. Along with proper training, soldiers need the courage to defend society’s interests before their own. The bravery, dedication, sacrifice, and sense of duty to protect and serve fellow countrymen should motivate recruits as much as any paycheck. Soldiers must have a calling to their profession. Being a professional soldier is not for everyone.

This ethos is important for building and maintaining a professional military. In Botswana, for example, citizens and members of the Botswana Defence Force (BDF) see the military as “the most capable of the country’s ‘disciplined services’…. Its members believe they are faithful stewards of resources entrusted by the nation to their care.”24 Thanks to this prestige, the BDF has the luxury of picking from a large pool of qualified candidates and has become increasingly selective in order to achieve the institutional culture it desires: highly disciplined, educated, and led by competent leadership. “In 2004 the BDF sought 80–100 new officers and received some 3,000 applications. It sought 500 enlisted recruits and received over 15,000 applications for these positions.”25

Significant steps have also been taken at the regional level to develop normative instruments to prevent military interventions in the political processes of African states. These include frameworks, such as the African Union’s (AU) “Common African Defence and Security Policy,” the “Framework for an African Union Response to Unconstitutional Changes,” the Southern African Development Community’s “Strategic Indicative Plan for the Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation,” and the Economic Community of West African States’ (ECOWAS) “Draft Code of Conduct for Armed and Security Forces.” The evolution of these explicit regional standards reflects a growing recognition of the need to improve the institutional culture of militaries on the continent. If upheld, these standards will have far-reaching implications for Africa’s political development.