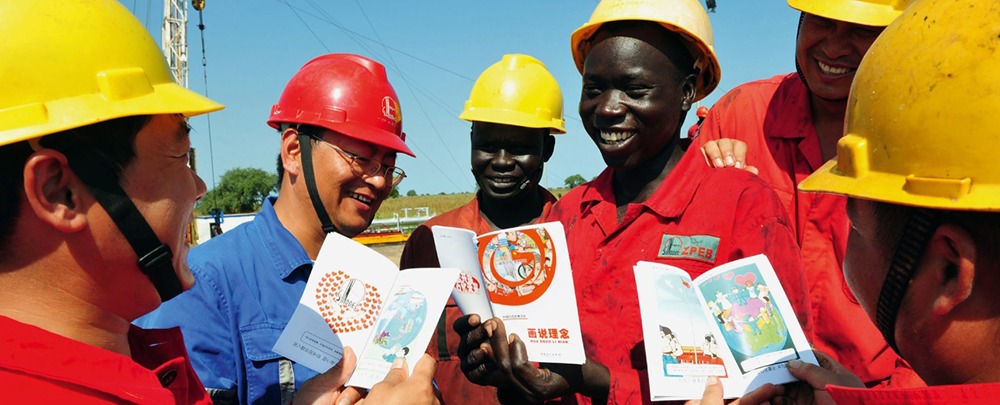

(Photo: Africa Business Magazine)

External engagement is playing an increasingly influential role in Africa’s security. China, the Gulf States, Turkey, and European countries, among others, have recently been ramping up their activities on the continent and sharpening their strategies. The Africa Center spoke with Judd Devermont, Director of the Africa Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, about the trends and complexities of these relationships.

Who are the central external actors in African security?

Judd Devermont

The international community is engaging in Africa in new ways and with more intensity across the board. In sub-Saharan Africa, 150 new embassies were built between 2010 and 2015. That’s mainly Turkey and Qatar, but Spain is also getting back into the game, as well as some Southeast Asian countries. Eastern Europeans are advancing their presence as well. We’re seeing a lot more diplomatic and commercial engagement, as well as a lot of security engagement with more and more countries building military bases on the continent—not just in Djibouti, but also in the Sahel and places like Cameroon. The biggest gainers are China, the Gulf States—especially the UAE and Qatar—and Turkey. There have also been smaller increases from some Western European countries who had previously drawn down their presence and now are building it back up.

What are some of the noteworthy drivers of increased external engagement?

For the Europeans, it’s driven largely by migration, which can be seen in the fleet in the Mediterranean Sea that’s policing Libya and Tunisia and Morocco, as well as support for the G5 Sahel, mainly by France, but also by Europe. As you move over to the Horn of Africa, you see countries like Qatar, the UAE, and Turkey building bases, increasing investments, and thinking about the security challenges. These countries have a long history in the Horn of Africa, but we saw some of their roles transform after the 2011 famine in Somalia, when they provided almost 30 percent of the humanitarian assistance. Since then, they have displayed more of a commitment to state-building. Finally, there’s the Central African Republic where we saw the Europeans come in, led by François Hollande from France. That’s been continued in a European training mission there.

How can African countries leverage these partnerships?

There is a lot of opportunity. First of all, countries should state clearly what kind of relationship they want from the external partners. I think Africans can be more specific and have more of a conversation about whether migration or any other topic is one that they want to focus on. It’s also imperative for Africans as well as international players to coordinate better to reduce forum shopping, redundancy, and duplicative engagement. These can flood the region with resources, but not necessarily in a very productive way.

I also think that African countries need to speak more loudly about when two countries are bringing their own rivalries into the continent and how destabilizing that is. The problems between Qatar and the UAE are becoming problematic for countries like Somalia and Sudan. There is also the rivalry between China and Taiwan. Burkina Faso recently switched relations from Taiwan to China, so now 48 of the 49 countries now recognize the One China Policy. But that is still a growing game. In addition, with the United States talking about Great Power competition, Africans are going to have to be more thoughtful about China-U.S. relations and U.S.-Russia relations.

More on: Regional and International Security Cooperation China