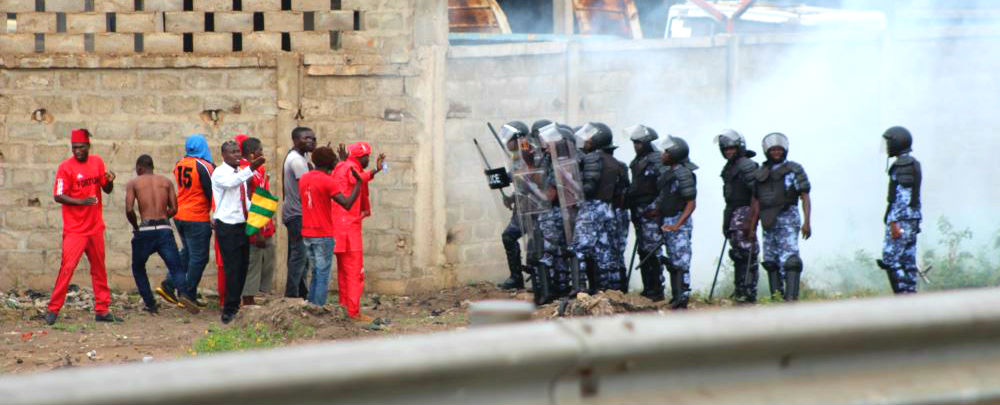

Togolese protesters before police in Lomé, Togo. (Photo: VOA/Kayi Lawson)

For two years, tens of thousands of Togolese citizens have taken to the streets to call for government reforms. One of their central demands is the establishment of presidential term limits that would force President Faure Gnassingbé out of office at the end of his current term in 2020. The issue is at the center of an effort by Gnassingbé to push through a constitutional amendment extending his time in office.

Faure was installed by the military in 2005 after the death of his father, General Gnassingbé Eyadema, who ruled the former French colony for 38 years. Two months after he took over the office, Faure won an election marred by fraud allegations and protests that left hundreds dead. In the aftermath, Faure promised to move forward with a comprehensive set of reforms that would guarantee free and fair elections. Faure won re-election in 2010 and 2015 amid similar accusations of fraud, and his pledge has yet to come to fruition. The next presidential elections are scheduled for 2020.

Faure has cultivated a culture of impunity in office. No one in the security service involved in the 2005 violence has been held to account, protesters arrested in recent demonstrations have reported being tortured while in custody, and the government has repeatedly shut down the internet to stifle demonstrators’ ability to organize. The protesters, who represent a cross-section of Togolese society, cite these human rights abuses and institutional breakdown, as well as persistent underdevelopment and endemic corruption, as the catalysts for their protests. One common refrain, “50 years is too long,” refers to the fact that the same family has controlled the presidency since 1967.

Tikpi Atchadam. (Photo: VOA/Kayi Lawson)

The National Pan-African Party, led by Tikpi Atchadam, is at the forefront of the opposition, having forged a coalition of 14 opposition parties and, in August 2017, organizing what had previously been sporadic protests into a consolidated movement. Tikpi’s rise as an influential opposition leader is particularly significant since he is a northerner, like Faure and his family. This has, therefore, created a new dynamic in Togo, which historically has been divided politically between the north and the south—the opposition stronghold. Protests were banned in the north, including in Sokodé, Togo’s second largest city and a base of the ruling Union for the Republic, after a crackdown on peaceful anti-government protests in October 2017 left at least four people dead and dozens injured. The government has officially banned protests and is violently enforcing the mandate. At least two people were killed by security forces attempting to break up a December 8, 2018, protest.

Term Limits

Formally adopted on October 14, 1992, Togo’s constitution established a two-term limit for the presidency. But in 2002, the parliament revised and amended the constitution to enable Gnassingbé to run for an unlimited number of terms. Opposition parties have been pushing for the return of term limits ever since. The public overwhelmingly supports such limits. A 2014 Afrobarometer survey found that 85 percent of Togo’s citizens “agree” or “strongly agree” that the president should be limited to two terms in office. The opposition coalition, as well as civil society movements such as Togo Debout (“Togo Rising”), have organized protests calling for the introduction of a two-term limit for presidents. Crucially, they say that the limit should be applied retroactively, effectively barring Faure from running again after his current term expires in 2020.

In response, the government introduced a draft bill in parliament to restore term limits to the constitution. However, it would not be retroactive, so Faure would be eligible to run for an additional two five-year terms, allowing him to stay in office until 2030. After failing to win approval due to a boycott by opposition lawmakers, the government called for the bill to be put to referendum on December 16, 2018—a poll that the government eventually called off due to protests.

A Politicized Security Sector

The Togolese security forces, especially the 8,000-strong army, have been intertwined in the country’s political system for decades, providing support to the regime whenever its grip on power was challenged. Members of Faure’s own Kabye ethnic group, which makes up around 20 percent of the population, comprise 70 percent of the army. Therefore, despite its relatively small size and limited assets, the army plays an outsized role and has a vested interest in maintaining the political status quo. Security services were behind the 2005 crackdown and have fired rubber bullets and tear gas to break up recent protests. Faure also continues to maintain loyalty from the top brass of the military and elite units of the presidential guard. Indeed, Security Minister Yark Damehame claims that only one person was killed in the Sokodé crackdown.

Civil Society

Dormant in the 1990s, Togolese civil society has experienced a notable resurgence due in part to the support of the diaspora. Though politically ostracized within Togo, the Togolese diaspora provides a valuable stream of funding back to its home country—remittances make up approximately 8.4 percent of Togo’s GDP—and have organized regular protests in cities like New York and Washington, DC, to raise awareness of the situation. In 2011, Farida Nabourema co-founded the “Faure Must Go” movement while she was studying in the United States. Largely organized through social media channels, the movement gave voice to the opposition and amplified its grievances. She remains overseas, and is, along with her family in Togo, regularly threatened by government loyalists.

“Elections without the necessary reforms will not solve the challenges facing the Togolese people but will, in fact, exacerbate tension and violence.”

Political space opened somewhat when the U.S. government’s Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) approved a $35 million program in Togo. The agreement, which will invest in two government priority areas—ICT and land tenure—is subject to Togo’s express commitment to democratic governance. The agreement also entails monitoring citizens’ rights to freedom of expression and association. MCC delayed the award until April 2018, when the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) appointed President Nana Akufo-Addo of Ghana and President Alpha Condé of Guinea to create a roadmap to end the country’s political crisis.

Catholic Church leaders, who usually avoid politics, have also become more vocal. The country’s powerful Conférence épiscopale du Togo (CET), criticized government plans to hold parliamentary elections in 2018. The elections are seen as a means of further insulating Faure from pressure to step down. On November 16, CET issued a statement saying, “It is obvious that the conduct of the elections without the necessary reforms will not solve the challenges facing the Togolese people but will, in fact, exacerbate tension and violence.” In August, Father Pierre Marie Chanel Affognon, chaplain of the Association of Catholic Leaders of Togo, penned an open letter to the government that said, “The basic democratic exigencies [the Togolese people] are calling for have been ignored by you, the political leaders,” who have instead responded by causing “several deaths, broken families, people who have simply disappeared, material destruction, exiles, arbitrary arrests, torture and imprisonment.” In December, Evangelical, Presbyterian, and Methodist leaders also called for the elections to be delayed.

ECOWAS

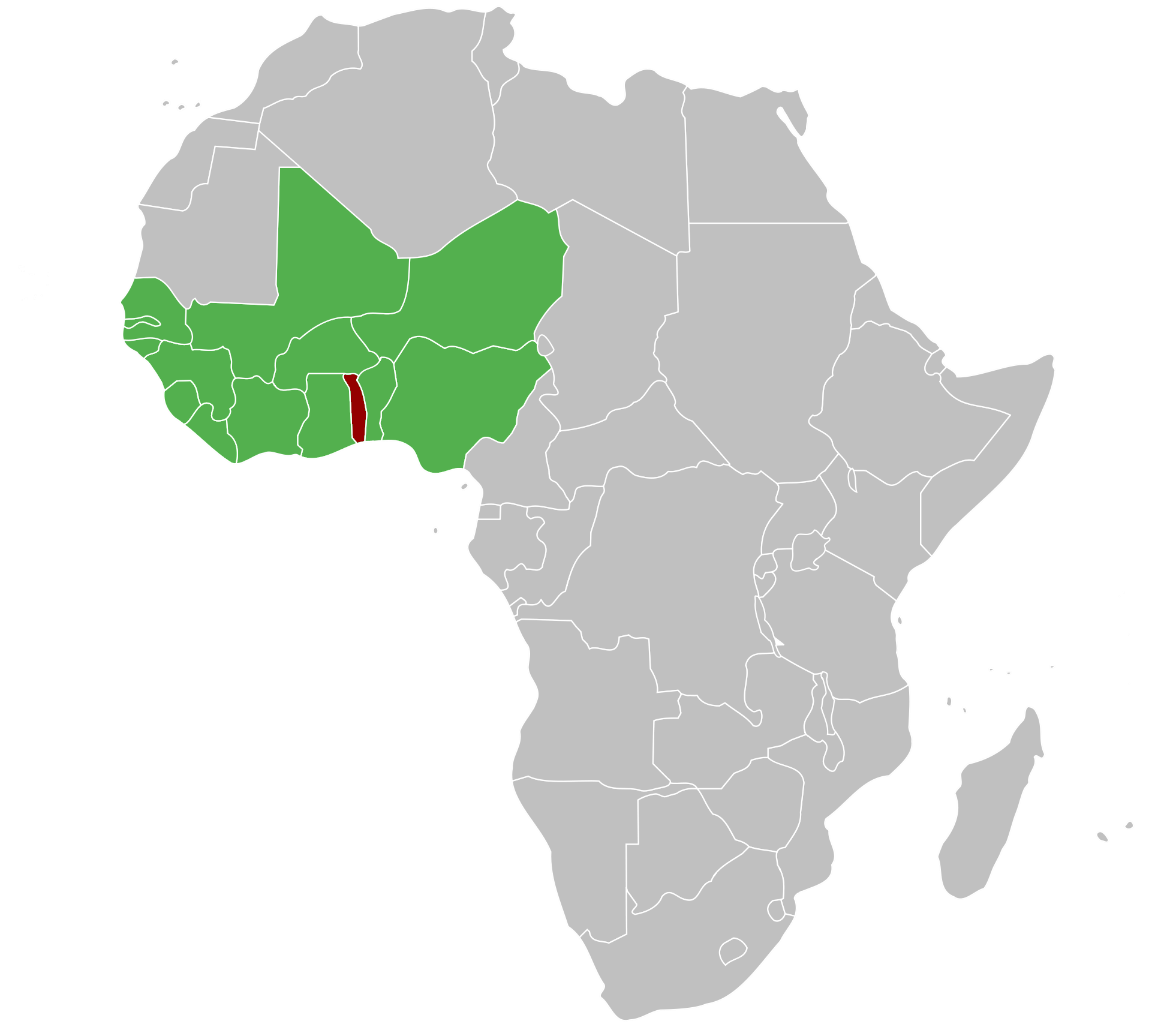

ECOWAS countries (green) with Togo (red).

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has demonstrated significant political will during past political crises in member states, such as in Gambia, Liberia, Mali, and Sierra Leone. This includes pressure on political leaders to uphold democratic standards and deployment of forces to reestablish stability. It is unclear if that active engagement will play out in Togo as well.

ECOWAS-mediated talks between the government and opposition began in February 2018. While the negotiations have yielded some results—for instance, the government has pardoned 45 political prisoners—it seems unlikely the opposition’s demands for a change of power will be met. At the July 2018 ECOWAS summit—held in Lomé—Akufo-Addo and Condé laid out a roadmap with recommendations on ending the political crisis, including instituting a two-round electoral system, making changes to the Constitutional Court, and improving the electoral process, including accelerating the electoral census to produce a more accurate voter roll, giving the diaspora the right to vote, and deploying election observers. In addition, ECOWAS leaders called on the security forces to remain professional while working to protect goods and people. They also called for restoring term limits. However, they did not weigh in on the central issue of retroactivity.

Protests in Togo quieted while Akufo-Addo and Condé were mediating negotiations and drawing up their roadmap. However, they were reignited in November, when Togo Debout called for the release of more than 50 jailed protesters and as news spread that the government had made significant changes to the roadmap, including adding non-retroactive term limits to the constitution. While ECOWAS has appointed a Senegalese constitutional scholar to make recommendations on how the original roadmap can be institutionalized, it has not pushed back on Faure’s stalling. ECOWAS’ depth of commitment to its democratic norms, therefore, is also under scrutiny.

The Path Ahead

“Togo is the only country in the 15-member ECOWAS bloc currently not on a democratic path.”

If Faure’s government adopts the term limit norms of other West African nations it could defuse the protests and avoid the risk of armed conflict. Such a transition must also involve a process for security sector reform. This would focus on strengthening norms of military professionalism, particularly de-politicization and the establishment of merit-based recruitment so that the force is more representative of the entire Togolese population.

The continued actions of the opposition and civil society organizations will be instrumental in demonstrating organizational capacity and resiliency in order to maintain domestic pressure for a transition that preserves peace and stability. Regional and international actors will then face a decision over the extent to which they are willing to uphold democratic norms in West Africa—or risk slipping back to the former status quo.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Term Limits for African Leaders Linked to Stability,” Infographic, February 23, 2018.

- Paul Nantulya, “Lessons from Gambia on Effective Regional Security Cooperation,” Spotlight, March 27, 2017.

- Boniface Dulani, “African Publics Strongly Support Term Limits, Resist Leaders’ Efforts to Extend Their Tenure,” Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 30, May 25, 2015.

- Émile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Research Paper No. 6, July 31, 2014.

More on: Democratization ECOWAS Togo