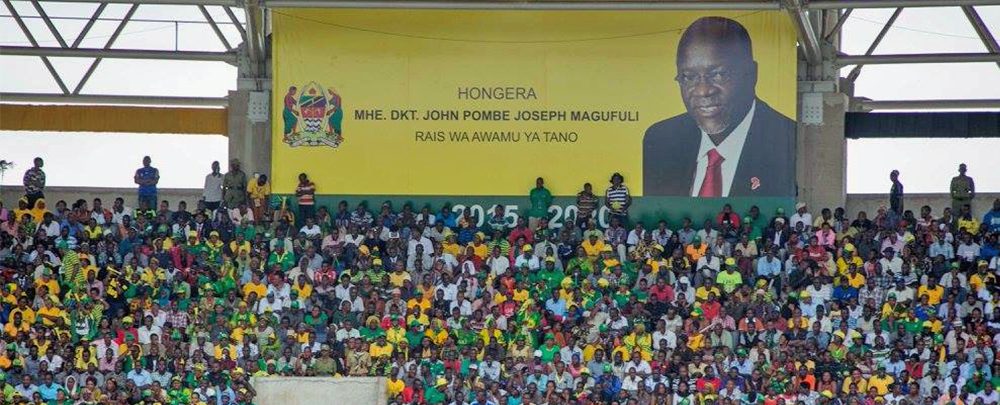

Swearing in of President of John Magufuli, Dar es Salaam, November 5, 2015. (Photo: Rwanda Flickr)

Since coming to power in 2015, populist President John Magufuli has presided over a precipitous decline of Tanzania’s democratic experiment. He has banned rallies, muzzled the press, cowed and co-opted independent institutions, and committed overt and covert violence against political opponents and “dissenters” within the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party.

Tanzanians today live in a climate increasingly filled with fear, reticent to exercise their rights lest they run afoul of a raft of new restrictive laws or suffer physical retribution. “Do not test me” were the menacing words Magufuli used when he banned rallies a few months into his presidency. This is the restrictive environment in which Tanzania’s October 28, 2020, presidential elections are to be held.

Ironically, many restrictions have been tightened in 2020 under the guise of combating the spread of COVID-19 even though Magufuli has declared Tanzania coronavirus-free. Tanzania’s lack of transparency in response to the pandemic is widely seen as having accelerated the virus’ spread in East Africa.

Tundu A. M. Lissu. (Photo: Likumbage)

The pattern of murders, assaults, and disappearances is epitomized by the brazen attack on opposition parliamentarian Tundu Lissu, who was shot 16 times outside his home in 2017. No one has been brought to account. Others have suffered similar fates. Respected journalist Azory Gwonda has been missing since November 2017, abducted while investigating mysterious killings in his community. Days later, Godfrey Luena, an opposition member conducting a separate investigation, was murdered outside his home by assailants wielding machetes.

As shocking as the political violence in a country renowned for its pacific population is the pace of Tanzania’s decline. Tanzania has dropped from 70th to 124th in Reporters Without Borders’ annual press freedom index during Magufuli’s time in office—more than any other country in the world over this period.

Tanzania’s founding President Julius Nyerere and the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM, or Revolutionary Party) conceived of African liberation as the building of inclusive democracy, a free press, tolerance of criticism, respect for minorities, and limits on power. Over the years, Tanzania steered more than a dozen political transitions in Africa, using its moral suasion and position to hold its fellow liberation movements to account on multiple occasions. Moreover, it has been intimately involved in numerous behind-the-scenes mediation efforts, including in 2017, when South Africa’s African National Congress turned to it for help in resolving its internal tensions preceding the resignation of Jacob Zuma.

“President Magufuli has banned rallies, muzzled the press, cowed and co-opted independent institutions, and committed overt and covert violence… This is the restrictive environment in which Tanzania’s October 28, 2020, presidential elections are to be held.”

Now, the CCM stands accused of engaging in the very practices it once roundly condemned. This is traumatic for many Tanzanians,” says Andrew Bomani, an independent commentator whose father, the late Justice Mark Bomani, worked as a senior aide to both Presidents Nyerere and Nelson Mandela and was the legal architect of Tanzania’s multi-party political system. “We had come to believe in a form of exceptionalism that such practices could never happen in our country.”

Return to a One-Party State?

The CCM is Africa’s longest serving ruling party, having been in power since Tanzanian independence in 1961. Magufuli clinched the CCM nomination in 2015 as an outsider amid an internal party split. The CCM old guard believed that a surprise candidate and technocrat untainted by the graft that had ravaged their party could win over a deeply disillusioned electorate. Instead, the opposite has occurred. Support for the CCM has plummeted as a result of the repressive environment.

Violence has become deeply embedded in CCM’s current calculus of control. In June 2020, Zitto Kabwe, leader of the opposition Alliance for Change and Transparency (ACT), was arrested along with eight senior officials for violating the blanket ban on gatherings. Weeks earlier, Freeman Mbowe, the president of the opposition Chama Cha Demokrasia Na Maendeleo (CHADEMA, or Democracy and Development Party), was assaulted outside his home by gun-wielding attackers who mockingly asked him if he would have the courage to continue his political activities. This episode is consistent with a pattern of critics who have died under unexplained circumstances—or disappeared without trace. Others have had their citizenship revoked or questioned.

Magufuli’s allies have used the CCM’s supermajority, which it has enjoyed since the advent of multiparty politics in 1992, to push through a series of harsh measures, which some see as part of a design to return to one-party rule:

- The amended 2015 Statistics Act criminalizes the publication of statistics without state approval. This politicization of data was criticized by many, including the World Bank, which warned that it would undermine the reliability and dissemination of factual information. Several journalists have been arrested, suspended, or fined under this law for reporting on COVID-19.

- The 2020 Miscellaneous Amendments Act grants the government powers to suspend civil society organizations and political parties and interfere in their internal operations.

- The 2020 Basic Rights and Duties of Enforcement Act was amended to forbid professional groups from filing cases on victims’ behalf unless they can prove that they too are victims.

Institutionalizing Impunity

“Support for the CCM has plummeted as a result of the repressive environment.”

In June 2020, CCM deputies passed a bill granting immunity to Tanzania’s top leaders for any action undertaken while in office. Nyerere’s close friend and distinguished constitutional expert, Issa Shivji, one of the few highly respected elders willing to speak out, authored a legal opinion criticizing the bill as an attempt to “amend the Constitution through a back door.” This, he writes, “has severe implications for the rights to life, livelihood, and dignity of the large majority of working people in villages and urban areas who are the primary victims of unconstitutional and illegal acts of the organs and officials of the state.” Emboldened by Shivji’s statement, Tanzanians mobilized 3,000 signatures in 48 hours to lobby Parliament to reconsider the bill. It was passed anyway, after which Parliament was dissolved to pave the way for the October election.

Magufuli’s effort to reshape Tanzania’s institutions to ensure impunity has extended to the judiciary, which has been weakened through Magufuli appointments that have been exercised without independent parliamentary vetting. Tanzania’s courts have sided with the state on every major issue under contention. In 2016, the Mtwara High Court threw out an application by human rights groups challenging the Media Service Act, which places severe restrictions on publishing. In January 2019, the Dar es Salaam High Court quashed a plea by lawmakers to halt legislation that expands the grounds on which opposition members can be suspended or jailed, including conducting voter education without government permission. In September 2019, the Dar es Salaam High Court threw out opposition leader Tundu Lissu’s petition against the revocation his status as a member of Parliament while he was overseas recovering from the assassination attempt against him.

In June 2020, Fatma Karume had her law license suspended by a High Court judge for launching a “rude” and “inappropriate” petition challenging the appointment of Adelardus Lubango Kilangi, a well-known CCM operative, as Attorney General. Karume is the daughter of retired Zanzibar President, Aman Abeid Karume, and granddaughter of Zanzibar’s founding president and co-founder of the Tanzanian nation, Abeid Aman Karume. In September, the High Court disbarred her permanently and the Tanganyika Law Society struck her name from the advocates roll, another indication of how independent institutions have buckled under executive pressure.

Under Magufuli, Tanzania has stopped working with the Africa Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights. (Photo: African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights)

In desperation, Tanzanians have taken their grievances to the Arusha-based African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the East African Court of Justice. The former has received over 100 petitions seeking remedies for the abuse of power, including injuries suffered at the hands of police. The government struck back in December 2019 by withdrawing the right of Tanzanian citizens to petition this court.

The National Election Commission is also firmly under executive control. During the 2019 local government elections, voters were told to register separately with regional and local administrations as the national voter registry had not been updated. These authorities are controlled by the president’s office, which wielded sweeping powers over the polls. This includes disqualifying numerous opposition candidates, including 95 percent of those from CHADEMA.

This prompted a mass opposition boycott amid which the CCM won 99 percent of the vote, bagging nearly 12,000 village councils and 4,000 town councils. With control of these councils, powerful local administrations, a partisan police force, and laws that silence the press and incapacitate the opposition, Magufuli is set to “win” another term and rule absent checks and balances.

Ongoing Resistance to Dictatorship

Despite these formidable institutional challenges, many Tanzanians continue to pursue democracy. Distinguished personalities like Shivji, Fatma Karume, and Nyerere’s former envoy to the Pan-African Movement in Algeria, Jenerali Ulimwengu, have refused to be cowed. This has been an inspiration to democracy reformers, given that the views of these leaders carry weight across the political spectrum in Tanzania. Justice Joseph Sinde Warioba, a former Prime Minister, Chair of the Constitutional Review Commission, and trustee of the Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation, urged the public to bring the proposed 2014 Constitution back into the national discourse. Its provisions include safeguards for the independence of the National Election Commission and other institutions, clauses allowing election losers to challenge the results in court, an enforceable ethics code, and the upholding of core national norms and values, among other reforms. The proposed constitution was rejected by the CCM-dominated Parliament before it could be put to a referendum.

“Despite these formidable institutional challenges, many Tanzanians continue to pursue democracy.”

Members of the public have appealed for the CCM Elders, a revered group of 21 Tanzanian and Zanzibari ex-presidents and prime ministers, also known as Stalwarts, to intervene, believing they can open a dialogue. Many have pointed to South Africa’s example, where nonpartisan engagement by Stalwarts of the ANC and institutions like the Nelson Mandela Foundation catalyzed civil society and Parliament, which ultimately pushed the ANC to embark on reforms. As is the case in South Africa, the CCM Elders are formally recognized by the CCM Constitution as an independent group and granted a permanent seat in the ruling party to act as a check on its powerful Central Committee. “They could not be removed, and their views had to be heard and respected,” explains Karume. It enacted a powerful peer review mechanism that is mostly remembered for shepherding the country toward multiparty democracy and facilitating the transitions from Nyerere to Ali Hassan Mwinyi to Benjamin Mkapa.

Karume recalls that Mwinyi had to “live with Nyerere’s sometimes caustic criticism of his government in the Central Committee and in public; Mkapa in turn had to live with criticism from Nyerere, Mwinyi, and [former Zanzibari president] Salmin Amour.”

As a former member of the Central Committee, Ulimwengu witnessed firsthand how the CCM Elders dissuaded Mwinyi from pursuing a third term. “Do not listen to what those hooligans are telling you,” Nyerere is said to have told Mwinyi. “They want you to stay on not because they love you, but they themselves want to stay on. I handed the baton to you in 1985 and in 1995, you must pass it on to someone else, period.”

The Elders’ role diminished with time, however. Former President Jakaya Kikwete believed it was too intrusive and introduced amendments that removed the Elders permanent seats and consolidated power within a smaller Central Committee answerable to the Party Chairman, who also serves as the President of the Republic. These changes continued under Magufuli with most members of the National Executive Committee and the Central Committee now appointed by the Party Chairman, a major violation of party traditions. The latter is also empowered—for the first time ever—to decide which candidates participate in party primaries and who goes to Parliament.

“The consequences of the CCM’s institutional drift have made it difficult for the CCM Elders to reprise their role as they can only convene with the authority of the Party Chairman.”

The consequences of the CCM’s institutional drift have made it difficult for the CCM Elders to reprise their role as they can only convene with the authority of the Party Chairman. CCM heavyweights who have spoken out risk being labeled wasaliti (traitors) and subjected to interrogation and punishment by the party’s feared security committee.

Given these dynamics, the momentum for change will likely have to come from outside CCM. Stepping up are groups like the Tanganyika Law Society, Tanzania Human Rights Defenders Coalition, and the Media Council of Tanzania who continue to file court injunctions, educate the public, petition regional institutions and the African Union, and forge coalitions with their counterparts elsewhere on the continent. “It is left to our institutions and us to check the executive,” says Karume. “The CCM does not have the requisite mechanisms or personalities for the job at hand.”

Returning to a Democratic Path

Under the current uneven political playing field and biased institutional environment, any Magufuli or CCM victory in the 2020 elections will be seen by many as lacking legitimacy. This will necessarily have consequences for ties between the Magufuli government and democracy-supporting regional and international actors.

President Magufuli meeting with South African officials. (Photo: GCIS)

In the meantime, Tanzanians can still draw on their longstanding norms as a source of resilience in navigating the way forward. Many recall the role the Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation played, in conjunction with the CCM Elders and senior figures from the ANC, during the 2001 post-election violence, when Tanzanians fled abroad in large numbers. It used its nonpartisan stature, unfettered access across political divides, and convening power to facilitate a months-long and inclusive national dialogue that crafted reforms that were incorporated into the Constitution.

Tanzania also has a wide pool of retired leaders who have historically been unafraid to hold the government to account. Pressure is mounting on them to muster the courage to intercede in their own personal capacities at this critical juncture. Faith-based bodies like the Episcopal Conference of Tanzania, Inter-religious Council for Peace in Tanzania, and the Christian Council of Tanzania are widely seen as the nation’s “moral conscience.” Their efforts to provide a safe space to channel and catalyze opinion and dialogue will be key.

“Regional engagement is vitally important given Tanzania’s historical role in continental affairs. This, however, must go beyond traditional diplomacy.”

Regional engagement is vitally important given Tanzania’s historical role in continental affairs. This, however, must go beyond traditional diplomacy, given that the CCM is still viewed as a senior leader and mentor by fellow ruling liberation movements, especially those in the Southern African Development Community. Overcoming their aversion to confronting the CCM will be a delicate exercise requiring multi-layered, track II engagements. Of particular influence are Stalwarts of high standing in South Africa, Namibia, and Mozambique who have historical ties to Tanzania and previously worked with the Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation. Given their seniority and impartiality, they can act as a bridge to facilitate a genuinely inclusive political dialogue in Tanzania, and one that can begin to rebuild Tanzania’s cherished democratic values.

Additional Resources

- Joseph Siegle and Candace Cook, “Assessing Africa’s 2020 Elections,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Spotlight, updated August 4, 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Subverting Democracy in Tanzania and Zambia,” Spotlight, September 17, 2019.

- Joseph Siegle, “A Time of Testing for Africa’s Democracies,” presentation at the Emerging Security Sector Leaders seminar, September 28, 2018.

- Telda Mawarire, “Tanzania’s Illiberal Tilt,” Project Syndicate, June 27, 2018.

- Joaquim Chissano, “An Open Letter to Africa’s Leaders,” The Africa Report, January 14, 2014.

More on: Democratization Tanzania