The U.S. Department of State has honored the Africa Center’s Dr. Assis Malaquias with an award recognizing his unique contributions in advancing maritime security efforts in Africa. Dr. Malaquias has been leading the Africa Center’s maritime security portfolio since 2009. In this capacity he has facilitated numerous discussions with African governments and Regional Economic Communities on strengthening Africa’s collective maritime security architecture. These efforts have contributed to the Yaoundé Declaration of June 2013 and the “Code of Conduct Concerning the Repression of Piracy, Armed Robbery against Ships, and Illicit Maritime Activity in West and Central Africa” in which 26 heads of government from West and Central African states agreed to formalize their cooperation on maritime security issues. To mark the occasion, Dr. Malaquias reflects on the current state of maritime security efforts on the continent:

The U.S. Department of State has honored the Africa Center’s Dr. Assis Malaquias with an award recognizing his unique contributions in advancing maritime security efforts in Africa. Dr. Malaquias has been leading the Africa Center’s maritime security portfolio since 2009. In this capacity he has facilitated numerous discussions with African governments and Regional Economic Communities on strengthening Africa’s collective maritime security architecture. These efforts have contributed to the Yaoundé Declaration of June 2013 and the “Code of Conduct Concerning the Repression of Piracy, Armed Robbery against Ships, and Illicit Maritime Activity in West and Central Africa” in which 26 heads of government from West and Central African states agreed to formalize their cooperation on maritime security issues. To mark the occasion, Dr. Malaquias reflects on the current state of maritime security efforts on the continent:

QUESTION: Why is maritime security so crucial for Africa’s economic development and security?

MALAQUIAS: Africa’s coastline is approximately 26,000 nautical miles. Its land mass of about 11,724,000 square miles is bounded in all directions by the sea—the Atlantic Ocean in the West, Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea in the North, and Indian Ocean in the East. Historically the continent’s pre-colonial coastal states and hinterland empires developed powerful navies and strong maritime cultures including the Gobroon Dynasty in Somalia, the Axumite Kingdom in Eritrea, and the Kongo Kingdom in Angola. This facilitated the region’s trade and security. Despite this distinctive geography and strong historical association with the sea, maritime domain awareness among Africa’s coastal states remains low today. This gap has been exploited by illicit traffickers in narcotics, weapons, migrants, and wildlife as well as pirates who have preyed on ships traversing the continent. This has made African trade more expensive and less economical. The lack of adequate security presence in Africa’s maritime spaces has also caused the continent to endure the highest level of illegal fishing in the world.

QUESTION: Why is maritime domain awareness lacking on the African continent and what can be done to change this?

MALAQUIAS: It has to do with perceptions of security as well as the nature of the modern African state. In the minds of military planners and decision-makers, the spheres that need to be protected are two: land borders and the seat of power. African militaries are organized accordingly. The maritime domain is an afterthought. It is not seen as vital for territorial integrity or regime survival. Maritime security is therefore one of the most neglected areas of African national security policy formulation. Even the vast economic potential of the maritime domain does not translate into the calculus of most of Africa’s leaders. Countries like Nigeria, Mozambique and Angola have started to shift their thinking given offshore oil and natural gas discoveries, however, even these have not been factored comprehensively into overarching maritime security strategies.

QUESTION: What would be required to change perceptions in security thinking?

MALAQUIAS: African states are slowly starting to realize that their continued development is intimately connected to the sea. However, the corresponding transition in policy thinking is not where one would wish it to be. This however is going to change. The continent’s growing population coupled with its demographic make-up is already impacting national, and even regime security. Underlying the popular protests we are seeing today is the failure to provide economic and livelihood opportunities for younger people. The youth bulge is now a reality. For many, lack of development is viewed as a function of lack of democracy. African countries will therefore have to become more serious about service delivery and about increasing the pace of development and these two tasks cannot be done without harnessing the maritime domain.

For many African countries like Gabon, Mozambique, Kenya, Tanzania and Cameroon, this means protecting vulnerable offshore oil and other maritime-borne natural resources. The maritime domain is also vital for Africa’s food security. Fish could account for a tremendous amount of the daily protein intake on the continent and yet fish stocks are not properly secured. Meanwhile, Africa’s share of fish in protein intake is the lowest in the world. This lack of food security, in an environment characterized by poor governance, skewed development, lack of service delivery, and the youth bulge is a major source of insecurity and it is only a matter of time before it leads to changes in the security and survival calculus on the continent.

The starting point to address gaps in maritime security is for security planners to take into account the concept of a “blue economy.” The maritime domain, in this new type of security thinking, is an important source of energy, food, and economic development. Tourism in Kenya, for instance, is that country’s second largest source of revenue. The maritime domain accounts for well over half of these revenues. In the “blue economy” the importance of shipping lanes, the safe passage of imports and exports, the safety of sea lines of communication, the prevention and management of oil spills, the safe operation of oil platforms, and the need to preserve fisheries are all important considerations.

QUESTION: What is being done by Regional Economic Communities to address gaps in maritime domain awareness and management?

MALAQUIAS: In 2012, the African Union adopted an important document, the African Integrated Maritime Strategy 2050 (AIM). It makes three important policy announcements. First, it acknowledges the vital importance of Africa’s maritime domain by stating that 38 African countries are either coastal or inland waterway states. Meanwhile, 52 of Africa’s more than one hundred port facilities handle containers and various forms of sea-borne cargo. Second, it states that numerous vessels, ports and shipyards provide thousands of jobs for Africans and, therefore, disruptions in Africa’s maritime system can have a costly economic impact. Third, it recognizes that fish makes a vital contribution to the food and nutritional security of over 200 million Africans and provides income for over 10 million.

This has direct implications for the estimated 46 percent of Africans who live in absolute poverty. Using the three announcements as a basis for engagement, AIM 2050 creates an overarching framework which challenges African countries to think comprehensively about their maritime domains.

The Regional Economic Communities (RECs) developed their own maritime security strategies in line with AIM 2050. In 2008 the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) adopted a maritime safety and security strategy that aims to ensure security by protecting offshore oil resources, fisheries and sea routes. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) followed suit in 2011 as did the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in 2014.

![A member of the Ghanaian maritime police looks at a suspected illicit fishing vessel prior to boarding. [Photo: U.S. Naval Forces Europe-Africa]](https://africacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/13776843044_cf0c965497_z-600x400.jpg) The RECs, in turn, are supposed to provide a framework for national-level strategies and work in this regard is already underway. Countries in the 11-member SADC, for instance, signed cooperation agreements at the 20th Standing Maritime Committee meeting held in Lusaka, Zambia in April 2014. These include agreements to establish maritime domain awareness centers (MDACs) in Mozambique and Tanzania that will be linked to existing MDACs in Durban and Cape Town. In addition, a cooperation framework agreement between Botswana, Lesotho, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Malawi is being finalized, as is a similar one on maritime cooperation between South Africa, Angola and Namibia.

The RECs, in turn, are supposed to provide a framework for national-level strategies and work in this regard is already underway. Countries in the 11-member SADC, for instance, signed cooperation agreements at the 20th Standing Maritime Committee meeting held in Lusaka, Zambia in April 2014. These include agreements to establish maritime domain awareness centers (MDACs) in Mozambique and Tanzania that will be linked to existing MDACs in Durban and Cape Town. In addition, a cooperation framework agreement between Botswana, Lesotho, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Malawi is being finalized, as is a similar one on maritime cooperation between South Africa, Angola and Namibia.

Much remains to be done in terms of maritime assets, capabilities, and tactics as well as strengthening legal, legislative and institutional arrangements but it is safe to say that new normative thinking about maritime safety and security is now taking root thanks to these continental and regional efforts.

QUESTION: What best practices are emerging and what are the prospects that these will be sustained?

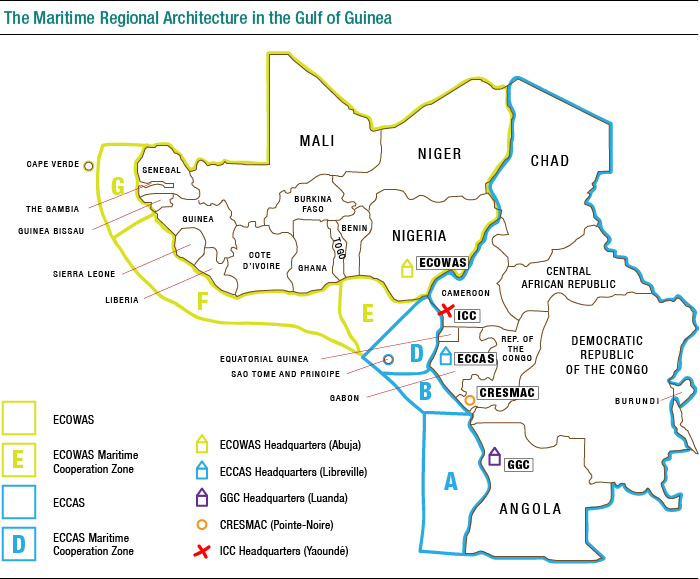

MALAQUIAS: The central notion of AIM 2050 is that security is dependent on development. The RECs are trying to operationalize this thinking by establishing maritime zones that can help organize the shared maritime space. ECCAS led the way in 2009 by activating the Regional Coordination Center for Maritime Security in Central Africa (CRESMAC) in Pointe-Noire, Republic of Congo. This Coordination Center is responsible for commanding three centers for multinational coordination (CMCs) one for each zone of Central African waters: Zones A, B and D, covering Angola at the southernmost tip to Cameroon at the northernmost end of the zone. The navies of these countries share information, coordinate anti-piracy activities, and have authorized protocols providing for the mutual pursuit of suspect vessels across maritime boundaries. The CMC for Zone D, for example, coordinates anti-piracy efforts by the navies of Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Sao Tomé and Principle. This collaboration has brought tangible results: it has led to a reduction in maritime crime and hostage taking as well as over 17 citations for illegal fishing resulting in hefty fines in Cameroon alone.

There are several lessons to learn from this experience. First, no single country can resolve maritime threats on its own. There is no way that Cameroon, for instance, can combat piracy without the collaboration of Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. National assets must synchronize and coordinate and they must be interoperable. Second, security resources are scarce. To be effective, regional maritime assets must pool resources and expertise. Third, legal frameworks are key. The lesson from ECCAS is that the principles set forth in AIM 2050 and in the CMCs must be domesticated into national laws to enable regional maritime coordination.

The ECCAS model has been replicated by ECOWAS both at the regional as well as national levels. This regional organization established similar maritime zones in West African waters: Zone E, F and G, extending from Nigeria to Senegal.

In East Africa, the problem of piracy in the Gulf of Aden and Indian Ocean has largely been addressed by the 25 nation maritime task force. This is not a sustainable solution, however. To do so will require enhancing maritime coordination and collaboration frameworks between Tanzania, Kenya and Mozambique. Absent strong regional cooperation, an array of maritime security threats will again surely emerge and expose this vulnerability.

Africa Center Expert

- Raymond Gilpin, Academic Dean, Africa Center for Strategic Studies

Additional Resources

- Assis Malaquias, “Africa’s Maritime Safety and Security Challenges,” video presentation at Next Generation of African Security Sector Leaders Seminar, October 27, 2014

- Adeniyi Adejimi Osinowo, Combating Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, Africa Security Brief No 30, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 2015

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Gulf of Guinea Maritime Safety and Security Primer, April 2015

- Liesel Louw, “What does ensuring SADC’s maritime security mean for South Africa?” South Africa, Institute for Security Studies, April 16, 2014

- Thierry Vircoulon, “Gulf of Guinea: A Regional Solution to Piracy?” International Crisis Group, September 4, 2014

More on: Gulf of Guinea Maritime Security