A seized Iranian dhow in the Seychelles.

Somali pirates hijacked a Seychellois-flagged vessel in February 2009 in what was the beginning of a steep escalation of maritime crime in its waters. Ten vessels were attacked that year in the Seychelles’ territory, leading to the loss of millions of dollars in tourism and fishery revenues. The country soon had to expend more resources on sea patrols. Insurance rates for vessels traveling through its waters increased as the security of cargo ships became imperiled by the surge in piracy in the western Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden. This was accompanied by an uptick in trafficking in charcoal, antiquities, and oil that were seen as a harbinger of more serious crimes—trafficking in humans, drugs, weapons.

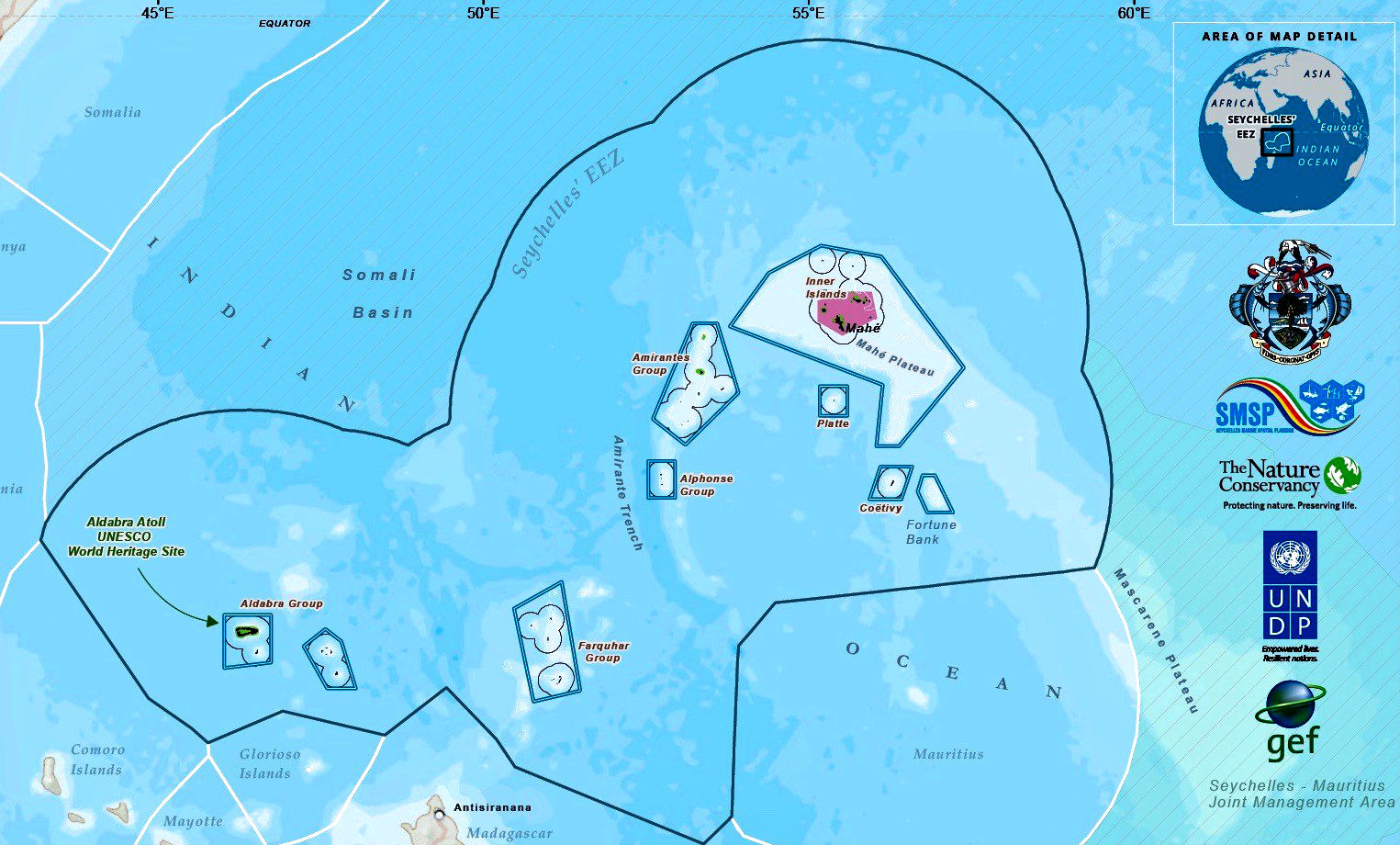

The Seychelles’ 455 square kilometers of land area is dwarfed by its 1.37 million square kilometers of sea. So its response to piracy and other evolving maritime threats—including unreported and unregulated fishing, pollution, and smuggling, among others—needed to be swift and innovative. Today its environmental, economic, and security plans include unique reforms and innovative partnerships generate benefits that reach well beyond its shores.

The Seychelles’ 455 square kilometers of land area is dwarfed by its 1.37 million square kilometers of sea. So its response to piracy and other evolving maritime threats—including unreported and unregulated fishing, pollution, and smuggling, among others—needed to be swift and innovative. Today its environmental, economic, and security plans include unique reforms and innovative partnerships generate benefits that reach well beyond its shores.

Security

Previously, the Seychelles had been limited in its ability to combat these crimes due to the same challenges many littoral countries face: overstretched correctional facilities, inadequate prosecutorial and judicial capacity, lack of IT infrastructure, too few interpreters to communicate with the accused, and unwillingness of witnesses to testify. But as crime was increasingly threatening the Seychellois’ way of life, the country was compelled to overhaul its security and legal systems in response.

In March 2010, the Seychelles amended its penal code to allow it to prosecute maritime crimes whether they were committed within Seychellois territory or on the high seas. The law afforded more flexibility in the pursuit of pirates who would travel in and out of territorial waters. This move was welcomed by the international community as it helped safeguard shipping lanes and enhanced the capacity to prosecute pirates. The reformed legal framework also empowered police and defense forces to seize ships and the property on board and arrest pirates. Since that time, the Seychelles has tried 66 piracy cases. In January, two men were sentenced to life in prison for smuggling opium and heroin in an Iranian dhow bound for Tanzania seized by the Seychelles Coast Guard in 2016.

Participants of a recent maritime security seminar in the Seychelles visit the Regional Center for Operations Coordination (RCOC).

Because of the Seychelles’ small size, it has prioritized regional and international cooperation in its security operations. The Seychelles hosts the headquarters of the EU-funded Regional Center for Operations Coordination (RCOC), which organizes the operational response to maritime crimes in the western Indian Ocean among its nine members: Comoros, Djibouti, France/Réunion, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, the Seychelles, Somalia, and Tanzania. In February, the Seychelles hosted Cutlass Express, an annual naval exercise sponsored by the U.S. Africa Command to improve maritime law enforcement capacity and promote security in the waters off of east Africa. In addition to the United States and the nine members of the RCOC, Australia, Canada, Denmark, Djibouti, Mozambique, Somalia, the Netherlands, and Turkey also participated in these exercises including boarding, search, and seizure drills, and workshops on identifying trafficking, piracy, and illegal fishing. Indian and Pakistani security forces have also collaborated with the Seychelles on maritime security concerns.

Environment

In February 2018, the Seychelles introduced the second largest Marine Spatial Plan in the world to chart out its maritime agenda. It is part of a deal dubbed “Debt to Dolphins,” in which The Nature Conservancy purchased $22 million of the Seychelles foreign debt to fund conservation initiatives. While similar deals had been struck in Latin America to conserve land, this was the first-ever debt-swap for marine protection. Under the agreement, by 2022, the Seychelles will increase the protected portion of its maritime domain from 0.04 percent to 30 percent for a total 410,000 square kilometers—an area the size of Germany. With these new protections, the Seychelles will significantly exceed the Sustainable Development Goal on ocean conservation to conserve at least 10 percent of its coastal and marine areas, and it will do so three years early.

The government and its partners held comprehensive consultations to solicit the input of local businesses and other stakeholders while developing the plan. In the first phase, almost all human activities have been restricted across 74,000 square kilometers surrounding the Aldabra Group, an UNESCO Heritage Site compared to the Galapagos Islands due to its biological diversity and environmental importance. Economic activities are allowed but restricted in a second 136,000-square kilometer area of deep water between the Amirantes Group and Fortune Bank that is vital to fishing and tourism interests.

The second phase of the plan, to be completed by 2020, will identify the remaining 200,000 square kilometers of waters to be protected. Because these will encompass more highly trafficked areas close to populated islands, the government is conducting additional consultations and gathering data before finalizing the plan. The remaining 70 percent of the Seychelles’ maritime domain that is not included in the newly protected areas will see increased regulations and oversight.

Source: IOC-UNESCO.

Economy

The environmental measures in the Marine Spatial Plan were developed to simultaneously shore up the Seychelles’ economy. Despite having one of the highest per capita incomes in Africa, the Seychelles’ economy remains reliant on the sea—specifically tourism and fishing. In the case of small island countries like the Seychelles, issues that threaten the health of the waters, such as pollution, coral die-offs, and ocean acidification, also threaten the health of the economy. By instituting aggressive measures to avert these hazards, the Debt to Dolphins deal is a prime example of a country leveraging national maritime domain potential to enrich the state and improve life on land.

Adopted in January, the Seychelles’ 2018–30 National Blue Economy Strategic Framework and Roadmap lays out plans for diversifying its investments in ocean-based industries, exploring new opportunities such as aquaculture and marine biotechnology, improving local food production systems and markets, and incorporating economic concerns, such as illegal fishing, in its national security strategy. The Blue Economy Department within the Ministry of Finance, Trade, and the Blue Economy—which itself is an innovation that asserts its commitment to conservation—will implement the roadmap, coordinating industries and other stakeholders that are impacted by—and that have an impact on—the marine domain.

Lessons

Many of the Seychelles’ innovations in securing its maritime environment are broadly applicable and instructive globally. Environment, economy, and security are dependent on one another. Threats like pollution and crime do not stay confined to one country’s waters, so states must coordinate information and operations regionally and internationally. Finally, as crime and environmental factors change, countries must be willing to adapt their security and development frameworks, legal codes, and other institutions along with them.

Africa Center Experts

- Ian Ralby, Adjunct Professor of Maritime Law and Security

- Raymond Gilpin, Dean of Academic Affairs

Additional Resources

- Anthony Fernando, “Adjudicating and Penalizing Maritime Crime,” video, March 22, 2018.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Enhancing Maritime Security in Africa,” program materials, March 2018.

- André Standing, “Criminality in Africa’s Fishing Industry: A Threat to Human Security,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 33, June 6, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Maritime Security in the Western Indian Ocean: A Discussion with Assis Malaquias,” Spotlight, May 26, 2017.

- Ian Ralby, “Cooperative Security to Counter Cooperative Criminals,” Defense IQ, March 21, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Maritime Safety and Security: Crucial for Africa’s Strategic Future,” Spotlight, March 4, 2016.

- Raymond Gilpin, “Examining Maritime Insecurity in East Africa,” Soundings, January 2016.

- Adeniyi Adejimi Osinowo, “Combating Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 30, February 28, 2015.

- Augustus Vogel, “Investing in Science and Technology to Meet Africa’s Maritime Security Challenges,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 10, February 28, 2011.

- Augustus Vogel, “Navies versus Coast Guards: Defining the Roles of African Maritime Security Forces,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 2, December 31, 2009.

More on: Maritime Security Maritime Security Seychelles