Ordinary Session of the African Union, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. (Photo: Office of the President of Rwanda)

Africa marks the 20th anniversary of the founding of the African Union (AU) in 2022. Much has been achieved. African countries have an institutional platform to engage other global agencies, financial institutions, and external actors.

Progress has also been made toward operationalizing the African Standby Force. The doctrine, command and control, force allocations, deployment scenarios, and logistics plans are in place and regularly exercised up to the brigade level. This was a long-held dream of the founders of the AU’s predecessor, the Organization of African Unity (OAU).

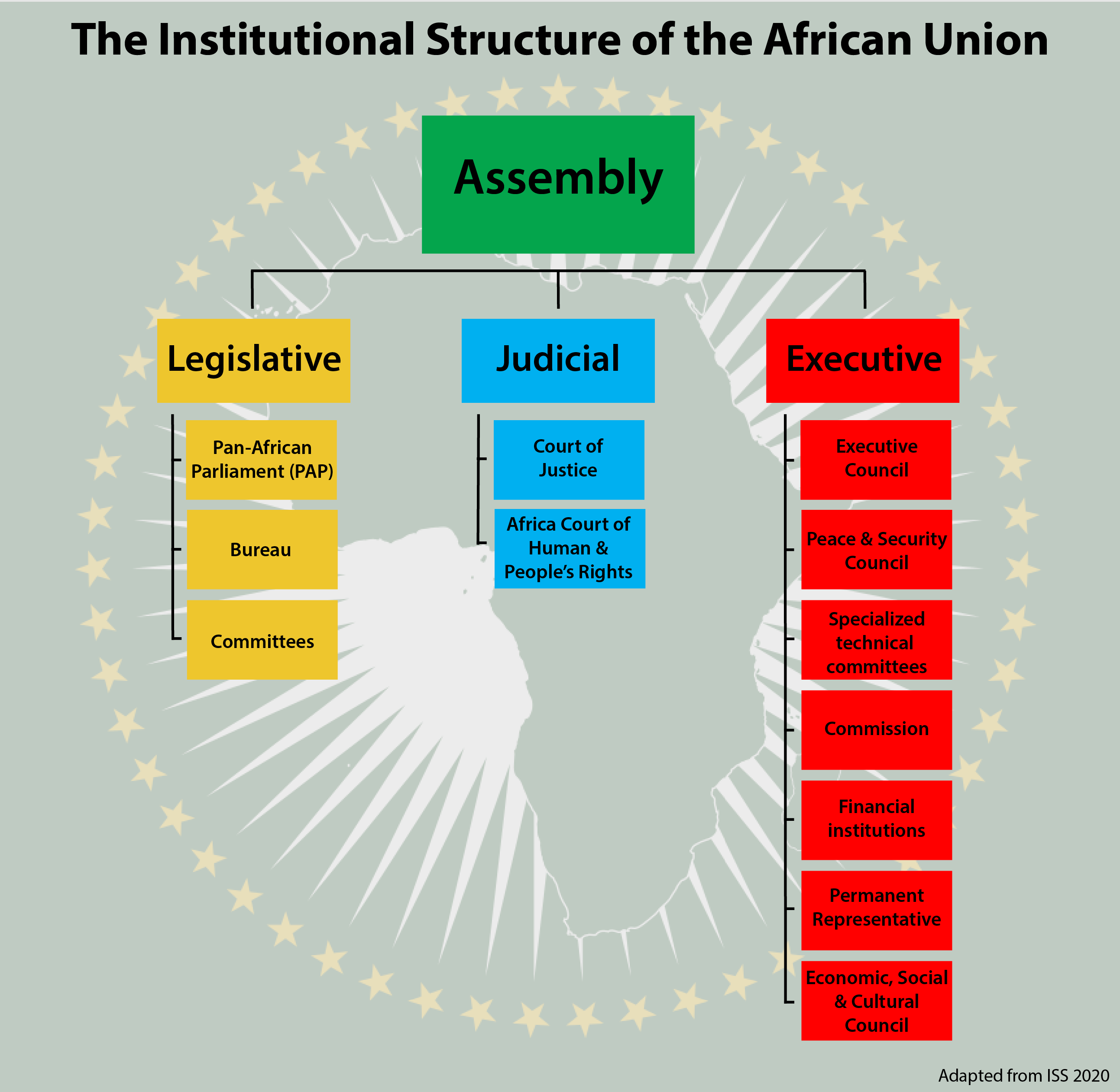

The challenges ahead are enormous, however. Contrary to the vision articulated in its Constitutive Act, the AU’s legislative, judicial, and technical organs remain weak, especially relative to the Assembly of Heads of State and Government, which comprises the leaders of its 55 member states. The Pan-African Parliament and the Economic, Social and Cultural Council—designed to give civil society organizations a voice within AU institutions—remain consultative bodies with no power. The African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, established to protect human rights and reduce impunity at the national level, remains hamstrung. Only 32 countries have ratified its protocol and of these, just eight accept its jurisdiction to hear complaints from citizens. Moreover, it is not permitted to sanction or investigate incumbent presidents.

Unsurprisingly, more than a third of Africans feel alienated from the AU or have no opinion on it.

The lack of political will to empower these regional institutions also weakens the commitment to common norms. Under the 2000 Lomé Declaration, the AU established a protocol for condemning coups and expelling offending member states. This rule has been implemented in Egypt (2013), Burkina Faso (2015, 2022), Guinea (2021), Mali (2020, 2021), and Sudan (2019, 2022). However, it was silent on others, such as Zimbabwe and Chad in 2017 and 2021, respectively. Furthermore, even in the cases where the AU implemented the protocol, the modalities for rehabilitation are unclear, as most offenders eventually wind up back in the AU with little or no consequences.

The AU is also not united over how to deal with term-limit violations. ECOWAS led the way in 2015 by introducing a nonretroactive two-term limit rule for its 15 members. However, resistance by two authoritarian members at the time—Togo and Gambia—caused it to stall, though the issue remains on the ECOWAS agenda. ECOWAS sent troops to remove Gambia’s Yahya Jammeh who refused to step down after losing an election in 2017. However, 2 years later, ECOWAS failed to stop Faure Gnassingbé from bypassing Togo’s constitution to hand himself a third term amidst a wave of deadly violence. The Gnassingbé family has ruled Togo as a hereditary dynasty since 1975.

Widespread frustration over such inconsistencies leads some Africans to dismiss the AU as a “presidents club” in the mold of its predecessor, the OAU, which faced similar criticism even from founding fathers like the late Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere. Some say the AU should be disbanded as it is perennially cash-strapped, unwieldy, and bites off more than it can chew. Others say the AU is being unfairly judged against impossible ideals as it is ultimately an organization of member states who must commit themselves to these norms.

Vision and Evolution

Established in 1963, the OAU led Africa out of colonialism but was ill-equipped for the new era. Two events in April 1994 crystalized the need for reform: the genocide in Rwanda and the end of apartheid in South Africa—stigma and euphoria. Intensive public consultations to amend the OAU Charter drew on debates launched by the Africa Leadership Forum in 1989, the OAU’s 1990 Declaration on fundamental changes in the world, and the findings of its investigative panel on the 1994 genocide.

As a result of these consultations, a powerful vision was laid out in the new AU’s Constitutive Act signed in 2000. The OAU’s “non-interference” principle was amended to a posture of “non-indifference” and “responsibility to protect,” even without consent—a lesson from Rwanda. The Act calls on the body to condemn coups and other unconstitutional changes of government. It also spells out conditions under which the AU can intervene when countries fail to govern responsibly, including genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. To that end, the African Peace and Security Architecture was established, and within it the African Standby Force.

The Act was designed for citizens’ interests to be at the center of all decisions. A Pan-African Parliament to be elected through universal suffrage, was created to ensure citizen participation. The Act also created the Economic, Social and Cultural Council (ECOSOCC), an elected assembly of civil society organizations, including professional associations, labor unions, and service bodies. A Citizens and Diaspora Directorate (CIDO) was established to facilitate the AU’s engagement with the African diaspora, which was recognized as the AU’s sixth region. African overseas citizens and people of African descent would have the right to sit on the ECOSOCC, engage the Pan-African Parliament, and participate in pre-AU Summit forums.

Inside the AU’s Program for Revitalization and Reform

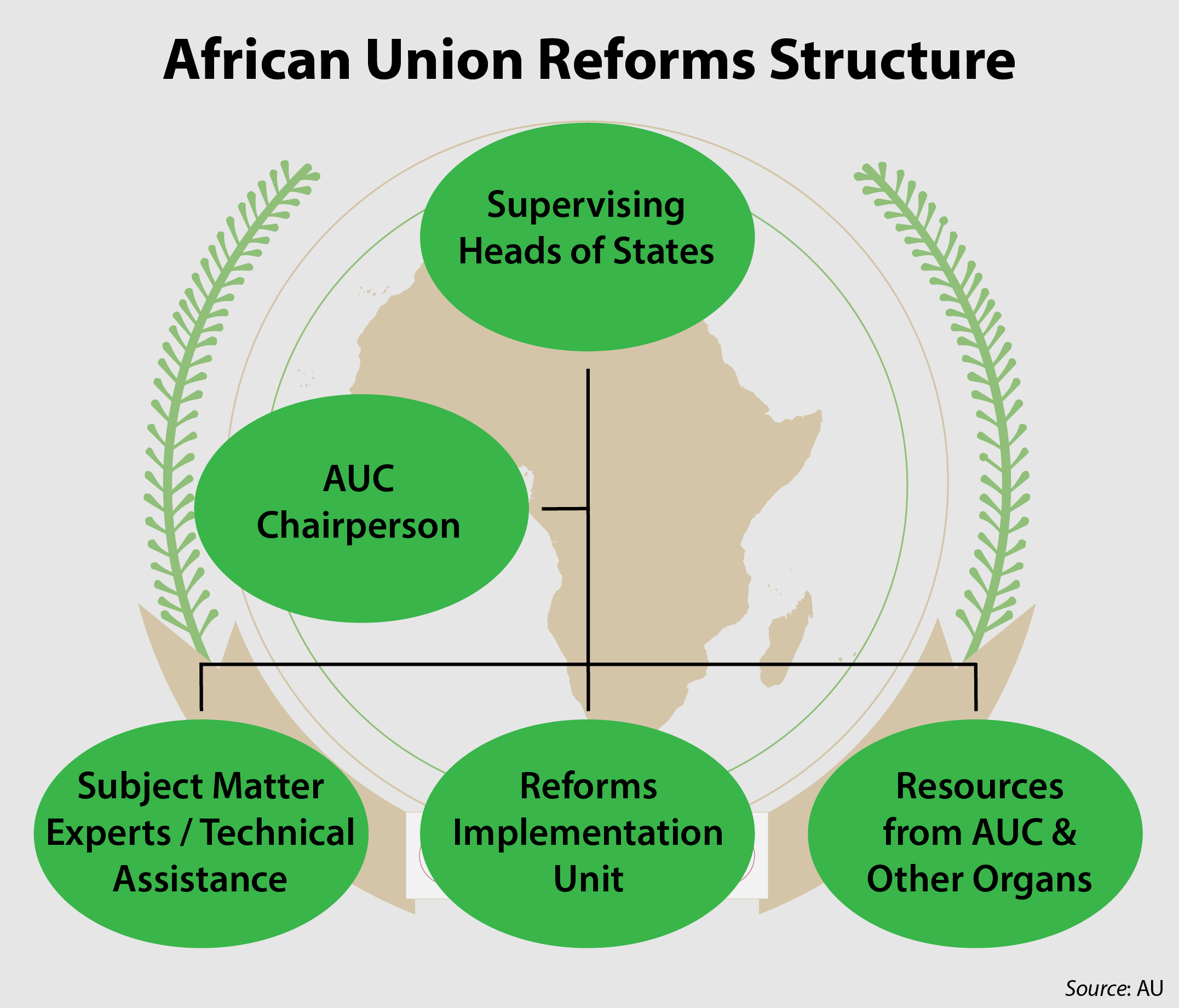

Reformers have suggested that a revitalized AU is achievable if the Constitutive Act is judiciously implemented without fear or favor. For this to happen, the AU must pare back, undertake deep reforms, rationalize its institutions, and renew itself. In 2016, the AU appointed Rwandan President Paul Kagame to lead what it called an “urgent and necessary” institutional overhaul. A team of eminent Africans from government, civil society, private sector, and international agencies was assembled to consult widely and deliver recommendations. They identified four bottlenecks:

- The AU was highly fragmented with too many focus areas.

- Its complicated structure and limited managerial capacity made it inefficient and unaccountable.

- It was neither financially independent nor self-sustaining.

- There was poor coordination between it and the Regional Economic Communities.

After 2 years of deliberations, they came up with a comprehensive plan for AU renewal:

- Refocus the AU’s priorities on fewer areas.

- Review its structure to realign institutions.

- Safeguard and expand citizens’ participation.

- Improve operational effectiveness.

- Enhance financial independence.

Specific proposals under each item were tabled before an extraordinary AU Reform Summit in November 2018. The merger of some organs and technical agencies, elimination of others, reduction of senior leadership and middle-management positions, and reorganization of the staff structure were quickly approved.

Proposals that had implications for the influence of heads of state, however, did not get as much traction. These included greater independence of the AU Commission, empowering it to recruit commissioners (the AU’s senior leadership team), and establishing full legislative power for the Pan-African Parliament to include voting by universal suffrage.

The African Union Flag (Photo: Arsen Shnurkov)

Other reform proposals sought to curtail the roles of the Permanent Representatives Committee (ambassadors) and the Executive Council (ministers) relative to the technocratic AU Commission. A motion to create a fully empowered African Court of Justice and Human Rights by merging the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the African Court of Justice was also tabled. The protocol for this merger was adopted in 2008 but has not been ratified. The reform team urged the AU Assembly to revisit the matter, describing the failure to ratify it as “a lack of commitment” by member states.

These proposals were considered by some as encroaching on the Assembly of Heads of States’ powers. Even approving the 0.2-percent import levy to boost the AU’s financial independence proved to be too much. Moreover, some political actors believe that the reforms would turn the AU into a technocratic agency like the UN, which has an institutional identity outside its member states—something opponents find unpalatable. Others believe that a more technocratic AU run by a professional and independent Commission with designated technical agencies could deliver more for the African people.

The issue of how much authority members are prepared to share to make the AU more functional is also a factor. Some believe that ultimate authority should rest with the Assembly of Heads of State rather than with a technocratic Commission sitting in Addis (AU headquarters) or an elected body in Midrand (the seat of the PAP in South Africa). Others push back from this interpretation, invoking Pan-Africanism—a core tenet of the OAU and AU—that emphasizes the transnational dimensions of African solidarity as well as its practical economic and security applications for addressing continental challenges. Its adherents argue that if AU reforms are anchored in Pan-Africanism instead of state-centrism, then its organs would be empowered, and it could then bring citizens to the center of its work.

Taking Stock: Restructuring Sans Renewal?

For now, the interests of the heads of state continue to prevail. They retain the power to select the AU Commission’s 6 commissioners. With the support of the AU Commission, its priorities were cut to four: political affairs, peace and security, economic integration, and amplifying Africa’s voice. The political affairs and peace and security dockets were merged into the new Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS) Department. Since the import levy has not been universally accepted, reliable independent funding for peace and security priorities remains an issue.

The larger reform agenda of enhancing citizens’ participation by empowering the legislative and judicial organs and giving more voice to ECOSOCC remain unresolved. The PAP has been variously described as toothless, pointless, and an empty shell—an indictment on member states. Rather than being elected directly by the people, parliamentary members are selected by national parliaments. They are restricted to collecting information and debating, and cannot make laws or binding decisions.

“Reform does not start with the Commission. It starts and ends with the leaders, who must set the right expectations and tempo.”

To be fair, institutions do not become functional overnight. The European Parliament, on which the PAP is modeled, also developed in fits and starts. It took 29 years to evolve from a marginal consultative organ into a powerful one that is elected by universal suffrage, exercises legislative power, and carries equal weight with the European Commission (the executive arm of the European Union) on matters of law, policy, and budget. Again, however, strong political will is needed for such institutional developments.

Similar frustrations abound about the AU’s financial position. The AU’s approved budget for 2022 was $650 million. Of this, $176 million was for general operations and $195 million for programs. Member state contributions cover 72 percent of these operational costs, which while commendable still falls below the goal of self-financing. Meanwhile, the entire peace and security budget of $279 million is still largely funded by donors.

In looking at this mixed picture, many within the AU fear that the heads of state have taken a minimalist view of reform focused on selective restructuring as opposed to renewal, which requires political will to allow AU organs to function properly. Consequently, organs like the African Standby Force risk remaining irrelevant no matter the competencies they have gained.

In June 2021, the AU was accused of double standards when it failed to sanction the generals in Chad after they imposed Mahamat ibn Idriss Déby Itno as ruler following his father’s untimely death. The AU justified its tolerance of the so-called Transitional Military Council by rationalizing that Chad was attacked by foreign mercenaries. The AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) was castigated for this controversial decision, but the real problem came from the presidents in the region who wanted the generals to stay and were loath to have them expelled from the AU. The AU, thus, is faced with the nearly irreconcilable task of balancing the enforcement of democratic norms with catering to individual leaders’ political interests.

African Union Reform Steering Committee Meeting. (Photo: Office of the President of Rwanda)

“Honesty requires us to acknowledge that the root problem is not primarily technical, but rather the result of a deeper deficiency,” the Kagame Report found. “Reform does not start with the Commission. It starts and ends with the leaders, who must set the right expectations and tempo.” The misalignment between the Assembly and other organs as explained in this report will continue to hamper the AU.

In December 2015, the PSC took a decision to deploy a peacekeeping mission to Burundi to stem the escalating violence triggered by then President Pierre Nkurunziza’s third term—a move deemed unconstitutional by EAC Attorneys General. This would have been the first deployment under the African Standby Force, and all systems were in place to put it on the ground by March. However, the Assembly of Heads of State swiftly rebuked the PSC accusing it of “overstepping its bounds.” AU credibility to serve as deterrent further evaporated when its Special Representative to the Great Lakes Region, Ibrahima Fall, said it never really intended to go in, describing the measure as “simply unimaginable.”

Public frustration over such dysfunction is shared by many inside the AU itself. A former Peace and Security Commissioner says that the AU must update the Lomé Declaration to explicitly outlaw the manipulation of constitutions, adopt a nonretroactive two-term limit rule, and craft a sanctions regime. This should be part of the security agenda as the abuse of term limits often leads to increased political instability and conflict.

The Elephant in the Room

“Many within the Assembly of Heads of State do not want a functional supranational body that empowers citizens, has the potential to hold leaders accountable, and may intervene if needed to protect African citizens.”

The gap between vision and reality is compounded by the elephant in room. Many within the Assembly of Heads of State do not want a functional supranational body that empowers citizens, has the potential to hold leaders accountable, and may intervene if needed to protect African citizens. Instead, as currently organized, the Assembly can overrule the AU’s executive, legislative, and legal bodies. This imbalance is seen in the increasingly divisive issue of term limits. Incumbents who pursue such measures can outmaneuver those working to preserve established democratic norms even though such norms are part of the Constitutive Act and the legally binding African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance.

A middle ground is possible. This would be an AU that responds to political direction but has the technical, managerial, and institutional competence to discharge its responsibilities.

For now, though, many Africans see the AU as an ad hoc mechanism that caters to presidents and prime ministers, rather than a functional agency that can deliver for them as envisioned in its protocols and conventions.

For many Africans, the viable pathway for the AU is the judicious implementation of the letter and spirit of its founding documents and additional protocols, particularly those relating to bodies designed to facilitate citizen inputs. The Pan-African Parliament is a good place to start. Only when the AU becomes truly Pan-Africanist, people-centered, and democratic, will African citizens feel they can readily support and defend the AU’s decisions, and even own its challenges.

Additional Resources

- Institute for Security Studies, “As the AU turns 20, it must speak with one voice,” PSC Insights, January 10, 2022.

- Ambassador Said Djinnit, “The Case for updating the African Union Policy on Unconstitutional Changes of Government,” Policy and Practice Brief, African Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), October 2021.

- Liesl Louw-Vaudran, “Pan-African Parliament’s woes reflect a crisis in leadership,” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, June 10, 2021.

- Joseph Siegle and Candace Cook, “Presidential Term Limits Key to Democratic Progress and Security in Africa,” Orbis 65, no. 3 (2021).

- Paul Nantulya, “The African Union Wavers between Reform and More of the Same,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 19, 2019.

- Lynsey Chutel, “The African Union has a brilliant plan for Africa, if it could get it right,” Quartz Africa, February 16, 2019.

- Institute for Security Studies, “The slow pace of ‘changing mindsets’ on AU reform,” PSC Insights, December 7, 2018.

- Peter Fabricius, “Does Africa really want a continental Parliament?” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, October 19, 2017.

More on: African Union