Download Full Report

Table of Contents

- Overview

- A Surge of Forcibly Displaced

- Drivers of Displacement in Africa

- Security Threats Related to Population Movement in Africa

- Current Strategies Are Insufficient

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

- Notes

- About the Author

Download Full Report

Table of Contents

- Overview

- A Surge of Forcibly Displaced

- Drivers of Displacement in Africa

- Security Threats Related to Population Movement in Africa

- Current Strategies Are Insufficient

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

- Notes

- About the Author

The population movement caused by political and structural drivers creates a spectrum of security implications ranging from the immediate humanitarian costs and empowerment of militant groups to the long-term socioeconomic consequences for the millions of affected households and the regions attempting to absorb those displaced.

The Bolstering of Criminal Networks

People traveling without proper documentation understand the threat of being deported by the authorities and therefore are less likely to seek assistance when in trouble. This opens the door to abuse—be it in the form of corrupt authorities demanding a bribe under threat of arrest or duplicitous human smugglers. Many of the passages that go through the Maghreb-Sahel region, for example, are pre-existing smuggling routes for arms and contraband—popular, precisely because they have little effective state oversight.

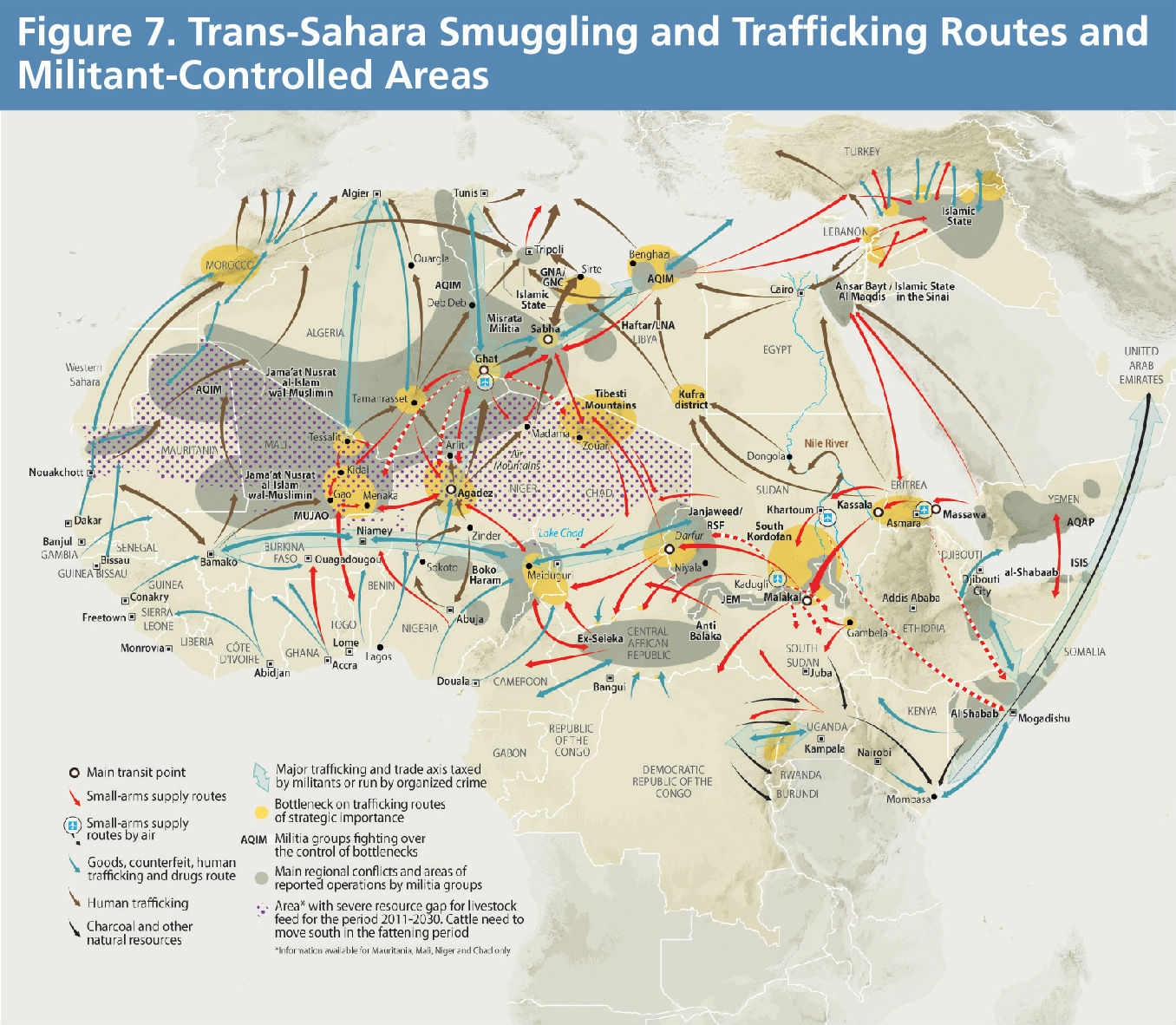

Having so much money floating along these routes attracts not just criminal elements but those who rely on the threat of violence to take control of a particular route, trade, or local community (see Figure 7). This has direct consequences for security in the affected country and region.

While the amount of illicit income generated from migration to Europe is inherently difficult to determine, estimates are that human smuggling along the Trans-Sahara route including Libya, alone, is worth up to $765 million annually.30

Source: RHIPTO/Riccardo Pravettoni29

A significant share of these resources is making its way into the hands of criminals, insurgents, and violent extremist groups who operate in a region that includes Algeria, Libya, Chad, Sudan, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. For example, the resources of persons travelling irregularly to the Libyan coast are enriching the many Libyan tribal militias and local officials who have been implicated in the warehousing and exploitation of migrants for labor. The annual revenue from the Libyan migrant market to all armed groups between 2016 and 2018 was estimated at between $93 million to $244 million.31 One Libyan militia commander sanctioned by the United Nations was the leader of a transnational trafficking network working directly with terror groups, including a longstanding relationship with the Islamic State (ISIS). ISIS, in turn, has a well-documented record of human smuggling and trafficking, abuse, exploitation, and murder of sub-Saharan Africans in Libya.32

While some Sahelian governments may see smuggling as a way of life and not a threat to the state, the inconsistent state security presence along these routes allows militant groups to become entrenched. Once in control of a smuggling route, militant groups can leverage their presence to extort money from all commercial traffic as well as impose protection taxes. Some estimates suggest that terrorist groups like the al Qaeda-affiliated coalition Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) could be drawing between $22 million and $38 million per year from taxation in the Sahel.33 This security risk has a major impact on all other economic activity, investment, and employment in the region. Moreover, as JNIM and other extremist groups have grown stronger in Mali, their attacks on the government (as well as regional security partners) have escalated, posing a direct threat to the state.

Similarly, as the market for human smuggling has expanded, more criminal actors have become involved, and some have been incorporated into international networks. The growing phenomenon of smuggling networks emanating from Libya have also contributed to instability and insecurity across the Maghreb and Sahel. Moreover, the phenomenon has taken on a life of its own with human smugglers actively recruiting more migrants. These actors are dipping ever further into sub-Saharan countries soliciting, luring, and coercing potential travelers. The OECD reports a growth in North African smugglers—Egyptians, Moroccans, and Libyans. “These smugglers then recruit unemployed youth in Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana to serve as recruiters in local communities.”34

While human smuggling is often depicted as providing migrants alternative paths of transit, human trafficking involves moving people against their will to then profit off of them either via labor or ransom. As one analyst succinctly put it, “In the case of human trafficking, the commodity is the control over a person for the purpose of exploitation. In the case of human smuggling, the commodity is the illegal entry into one or more countries.”35 Increasingly, human smuggling to the Libyan coast has crossed the line into human trafficking as it moves from transactional to exploitative.

The criminal activity and corruption associated with trafficking undermine domestic stability and the rule of law.

For thousands of migrants heading for the Mediterranean this has meant being held by their smugglers for ransom, forced into debt bondage to pay off suddenly increased rates, or simply sold to traffickers for further exploitation. Human Rights Watch documented the kidnapping and torture of Eritreans in Sudan and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula by kidnappers who were able to coerce between $20,000 to $33,000 per victim from the Eritrean diaspora in Europe and the United States. Similar practices have been documented occurring in Libya and the Horn.36

When people are trafficked, unlike people traveling of their own free will, they do not send remittances back to their home countries. In effect, the victim’s family, community, and country lose out on their earning potential. Further, the criminal activity and corruption associated with trafficking undermine domestic stability and the rule of law.

In weak states the smuggling of illicit goods and people and the armed groups perpetrating it also inhibit state building. As the East Africa regional bloc, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, has noted, “[g]iven the scale of the human smuggling business in Libya, there can be little doubt that migrants and refugees have become a commodity fueling the war economy in the region and contributing to the centrifugal forces responsible for the enduring breakdown in law and order.”37 The United States Institute of Peace has similarly recognized the difficulty of getting rival actors to the negotiating table to consolidate governmental authority when “the very logic of trafficking and smuggling, which relies on tenuous controls of the state’s periphery, is an incentive for armed groups to maintain a weak state rather than allow a strong one to be rebuilt.”38

The Human Costs of Displacement

Under threat from conflict, people flee with little to nothing of their possessions. Among the displaced are merchants and traders, their displacement severing the ties that connect these communities with regional markets, accelerating economic decline and inhibiting recovery. After conflict, investment tends to dry up for years and sometimes decades. A single year of civil war is estimated to reduce a country’s economic growth by about 2 percent and its neighbors’ by about 0.7 percent of their GDP.39

The vast majority of people fleeing conflict, importantly, stay within their countries (IDPs). Of those who leave their country (refugees), most flee to the nearest accessible border and stop their flight there. In other words, their primary objective is to get out of harm’s way. The implication is that forced displacement is a regional problem where border towns bear the bulk of the burden. IDPs, refugees, and hosting authorities often anticipate that the displacement will only be temporary. However, failing the timely resolution of the political crisis that has caused the displacement, IDP and refugee populations tend to persist. The average duration of exile for refugees globally today stands at 10.3 years.40 For IDPs it can be as long as two decades.

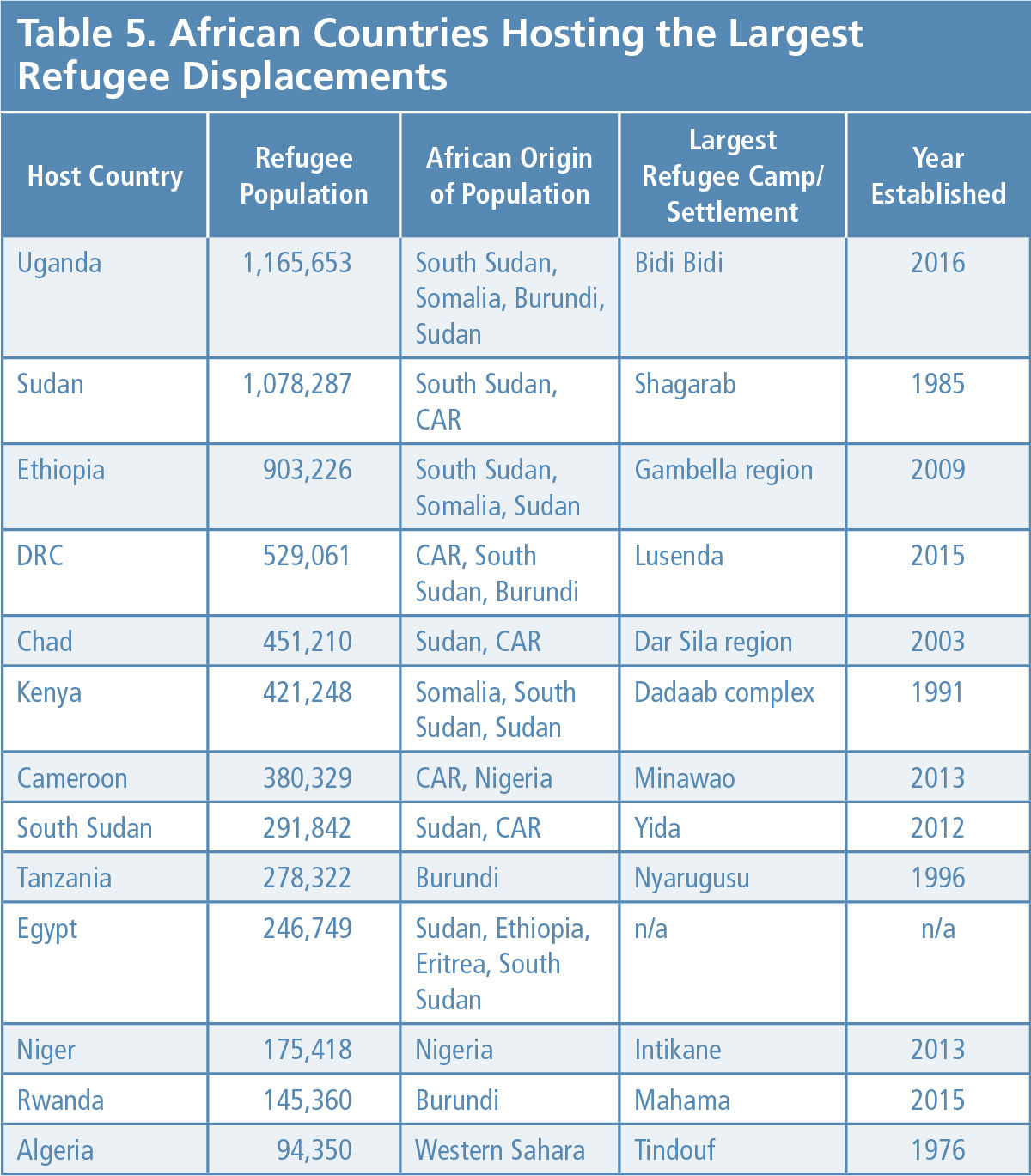

Of the more than 7 million refugees on the continent, around 60 percent live in camps.41 Just a few countries—Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopia, and the DRC—are hosting the lion’s share of refugees (see Table 5). In 2017, Uganda became the largest host nation of refugees in Africa. The border towns of northern Uganda, a region with an estimated population of just 1.9 million, have absorbed some 726,000 South Sudanese refugees.

Hosting displaced populations (be they refugees or IDPs) for long periods of time is problematic for numerous reasons. Not only are a hosting community’s resources severely strained, but the coping strategies of the displaced are likewise stretched thin if not broken. Once they have missed their harvests or planting seasons, the displaced are dependent on others for at least another year. The cycle spirals downward. Often, governments turn to humanitarian organizations to assist. But with many crises dragging on year after year, donor fatigue dries up resources and both the displaced and host governments face severe strains for years.

As the pressure on host communities builds, the potential destabilizing effects expand. For example, as the South Sudan crisis endures, the risks of instability in northern Uganda, a region with its own legacy of strife, will escalate. Similar patterns can be seen as a result of political crises in Burundi, CAR, the DRC, and Somalia.

Large settlements of people displaced within and across borders by protracted intrastate conflicts may also become targets or recruiting grounds for rebel groups, gangs, or other illicit actors. This is especially a risk when the displacement is perceived to have an intercommunal dimension, creating a defining identity within the victimized group and a lever for recruitment by sympathetic actors. To the extent that this displacement crosses borders, it may also draw in neighboring countries fueling extended regional instability, as arguably has been the case for years in the Great Lakes region.