Download Full Report

Table of Contents

Download Full Report

Table of Contents

For many African governments of migrant origin countries, the outflow of mostly young and able-bodied men who comprise the majority of economic migrants may appear to provide a release valve for potential political crises due to unemployment, urban overcrowding, and other socioeconomic concerns. Plus, those migrants who successfully find employment in another country send money home. World Bank data reveal that migrant remittances can be an important part of a country’s GDP.

However, as noted earlier, displacement contributes to a host of unforeseen security concerns, including for the country of origin. Moreover, certain countries are experiencing reoccurring waves of forced displacement due to ongoing conflict. In effect, those unresolved political crises are being externalized to their neighbors. These neighbors and international actors have used various methods to respond to the large influxes of vulnerable populations crossing their borders with mixed effect.

The African Union: A History of Good Intentions but Inconsistent Implementation

Since the wave of independence in the 1960s, the Organization of African Unity (OAU), now the AU, has envisaged the free movement of persons as essential to continental socioeconomic integration. However, the majority of AU member states have been slow to take concrete action to make such integration a reality.

In 1991, the OAU passed the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community, commonly known as the Abuja Treaty, which set up the framework for a continent-wide economic community including the free movement of persons. In 2006, in recognition that “well-managed migration may have a substantial positive impact for the development of countries of origin and yield significant benefits to destination States, [while] mismanaged or unmanaged migration can have serious negative consequences for States’ and migrants’ welfare, including potential destabilizing effect on national and regional security,” the AU met in Banjul to adopt a policy on migration from which African countries could borrow, adapt, or use to inform their own national and regional migration priorities.42 The framework addressed a comprehensive range of migration issues in Africa: labor migration, irregular migration, forced displacement, internal migration, the collection of migration data, border management, migration and development, and interstate and interregional cooperation. Though comprehensive, the framework was nonbinding, and few governments used the elements within it as intended.

Unresolved political crises are being externalized to their neighbors.

In recent years, individual countries have gone even further to ease travel. In 2016, the Seychelles was the only visa-free country for all passport-holding Africans. Since then, nine other countries have allowed all passport-holding Africans either visa-free entry or visas on arrival. These efforts are in line with the AU’s goal to roll out a passport for all African citizens in accordance with its Agenda 2063. Meanwhile, in 2014 Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya agreed to allow their citizens to travel freely across their shared borders using only a national identity card—a measure that increased cross-border trade by 50 percent between these three countries.43

In its 1969 Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, the OAU encouraged its member states to assist and protect a broader definition of “refugee” than already existed in international law, one that was more reflective of the reality on the ground. The Convention was subsequently ratified by 46 member states. This was supplemented by the AU Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (the Kampala Convention) in 2009, which committed governments to protect the rights of and provide for the needs of all citizens (including host communities) affected by displacement due to conflict, natural disasters, or development projects. Signed by 40 member states and ratified by 27, the Convention went into force in 2012. Despite these two legal instruments, implementation of assistance to refugees and IDPs has been uneven at best.

Since 2006, Uganda has championed a model of allowing refugees the right of free movement, labor, and integration within host communities. This approach has slowly been gaining currency among other African countries. Unfortunately, the massive number of refugees, mostly from South Sudan, has made continued provision of benefits more difficult. Some towns in Uganda, such as the greater Adjumani area, are home to almost equal numbers of refugees as local residents.

At times, a country’s well-intentioned policy to provide protections for forcibly displaced persons has created loopholes for exploitation and corruption. South Africa, for example, has seen its asylum seeker management system overwhelmed by economic migrants. While South Africa allows asylum seekers to live and work anywhere in the country pending determination on their asylum claim, its laws make it difficult for other types of migrants to live and work in South Africa legally. Consequently, among legitimate asylum seekers, there are others who have asked for asylum just to get the right to work during its processing.44 This has done little to help the animosity and discrimination against foreigners, especially during economic downturns.

Despite 32 countries signing the Protocol on Free Movement as part of the African Continental Free Trade Area framework of 2018, the eventual free movement of African citizens throughout Africa, seems distant in practice. To reach this goal there would need to be crucial improvements in each country’s population registration systems, shared border management, bilateral return agreements, and consistent law enforcement at the national level.45 Moreover, destination countries like South Africa and those in North Africa where unemployment is high face backlash from citizens if borders are opened to economic migrants. Without a more specific roadmap to establishing the free movement of persons across the continent—one that addresses both the real and perceived obstacles—little practical progress can be expected. Thus far, only one country—Rwanda—has ratified the Protocol on Free Movement.

International Assistance: Short-Term Objectives Adding to Long-Term Challenges

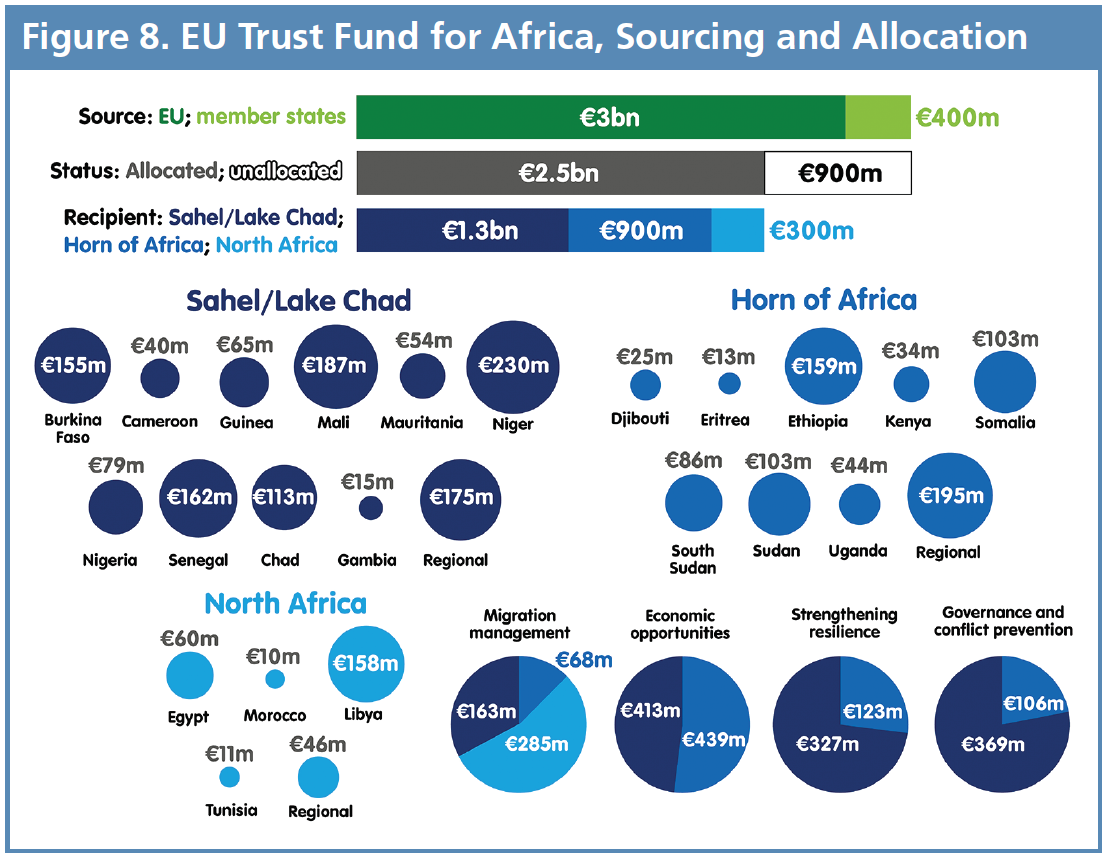

The close proximity of Europe to Africa has facilitated a long shared history that has culminated in some 9 million Africans living in Europe today. This relationship has included various attempts to manage and mitigate irregular migration across the Mediterranean. In 2006, for example, the Euro-African Dialogue on Migration and Development (the Rabat Process) began as a means to stop irregular migration flows and develop institutional cooperation in managing migration from West Africa to Europe. In 2014, the EU-Horn of Africa Migration Route Initiative (the Khartoum Process) was launched with a similar goal between East African countries and the European Union. With the number of undocumented migrants from Africa continuing to rise, in 2015, the EU set up a €1.8 billion ($1.93 billion) migration and development trust fund for programming designed to impact 23 countries comprising the Sahel, Lake Chad, Horn of Africa, and North Africa regions (see Figure 8).47

Source: European Council on Foreign Relations46

Despite the comprehensive nature of several of these initiatives, many policy analysts and refugee and migrant activists have pointed out that the majority of EU resources go toward “border control, security, and measures to restrict migratory flows” rather than address root causes of migration.48 Instead of stopping the flow, these policies have redirected it to less patrolled and more dangerous routes, raising the cost of smuggling and the risk to migrants. They have also contributed to the rise in the number of migrants trapped in horrific conditions in North African countries.

EU members moreover have been partnering with repressive regimes known for their poor human rights records, including Eritrea and Sudan. In other words, the very governments causing the largest displacement of people have been rewarded with legitimizing attention and assistance.

Sudan, which is responsible for the internal and international displacement of almost 3 million of its own people, was initially allocated €100 million ($114.65 million) from the EU trust fund to support basic services (education and health), livelihoods and food security, civil society, local governance, and peacebuilding. Since then, Sudan has been allocated additional funding for programs to stem irregular migration of Africans across Sudan toward Europe.

In 2016, the main opposition leader in Sudan alleged that the EU funding was instead being used to arm the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group comprised of former Janjaweed militants who had carried out ethnic cleansing in Darfur.49 Even though the EU issued a statement assuring that it was not funding the RSF, the RSF itself affirmed that it was involved in “fighting illegal migration” and that it had received new vehicles as a result.50 In 2017, the Sudanese government made the RSF an official, but autonomous, part of the national military whose mandate includes border protection. In 2019, the RSF was responsible for the violent crackdown in Khartoum and other parts of Sudan on unarmed protesters demanding an end to military rule.

In the transit country of Libya, the UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) and Italy signed a bilateral agreement in 2017 for €200 million ($215 million) intended to limit the number of people travelling from Libya to Italy. The EU acknowledged its support of the deal that included training and equipping the Libyan Coast Guard and funding existing detention centers affiliated with the GNA’s Ministry of Interior as temporary migrant reception centers. This agreement followed a December 2016 report by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights that found migrants were subjected to arbitrary detention, torture, other ill-treatment, unlawful killings, and sexual violence in official and unofficial detention centers.51 Investigative reporting, furthermore, documented the Libyan Coast Guard not coming to the aid of drowning migrants in the Mediterranean but rather preventing other rescue boats from safely aiding the drowning migrants.52 The UN subsequently imposed sanctions against a Libyan commander of the Coast Guard based in Zawiya for his involvement in those activities.

In sum, many find that while the EU-supported approach to migration management in Africa may have reduced the flow of African migrants to Europe since 2017, it has done little to address the drivers of migration or alleviate the abuses suffered by African refugees and migrants seeking to come to Europe. This suggests that the reduction in migrant flows is likely temporary. Moreover, EU policies have arguably empowered and emboldened the actors committing the abuses contributing to at least 12,000 deaths and the forced return of an estimated 40,000 to their abusers.53

Lessons from Previous Migration Crises

The Comprehensive Plan of Action for Indochinese Refugees

Set up in response to the wave of “boat people” fleeing communist Vietnam, the 1989 Comprehensive Plan of Action for Indochinese Refugees (CPA) was the first time the international community introduced the use of in-country applications for asylum.54 This initiative was aimed at mitigating risks faced by asylum seekers vulnerable to criminal elements—not unlike what is happening on African migration routes now.

The international community convinced the Vietnamese government to permit in-country asylum screenings and the issuance of visas to those who qualified for asylum, allowing refugees to migrate through legal channels. Mass media broadcast the new procedures for in-country asylum applications along with a warning about the dangers would-be sea farers faced employing clandestine boat departures.

Despite shortcomings in its execution, the CPA allowed the international community to resettle Vietnamese refugees while also enabling more refugees to switch from the dangerous, clandestine routes to safe, legal migration channels.55

MERCOSUR

Like the AU and its RECs, South American governments and regional organizations have long been contemplating better regional initiatives for freedom of movement of their citizens. One promising approach, in force since 2009, has been the MERCOSUR (the Southern Common Market) Residence Agreement.56 The agreement allows citizens of the nine signatory states the right of residence and permission to work with proof of a valid passport, birth certificate, and police clearance. Among other benefits, member migrants are promised equal civil, social, cultural, and economic rights as citizens of the host country. Before the expiration of their 2-year temporary residence, they may also apply for permanent residence in the host country.

The agreement came about as a result of the member countries’ desire to address irregular migration in a region that has a large informal economy.57 Despite inconsistencies in the application of various aspects of the agreement within and across member states, the member countries appear to recognize the value of the mutual protection of their citizens.

Philippines

In another model, countries with longstanding migrant links have established intergovernmental agreements to allow for a regularized flow of migration between origin and destination countries to better protect the individuals and countries themselves. For example, in recognition of the fact that large numbers of Filipinos migrate to Macau and Hong Kong for work, the Philippine government has engaged the two destination governments for the benefit of all parties. The Philippines government, in cooperation with the Philippines Red Cross Society, ensures not only visas and safe transport but also pre-departure orientation seminars for potential workers. In Hong Kong, the Philippines’ consulate plays a role in negotiating standardized contracts for all Filipino domestic helpers, specifically with the goal of preventing abuse and wage theft.58 The government of Macau has even allowed the Philippines Red Cross Society to set up a local chapter to provide welfare, crisis intervention, and other services to female Filipino domestic workers. This has been instrumental in protecting the rights of Filipinos working abroad while ensuring a positive economic relationship between the governments.