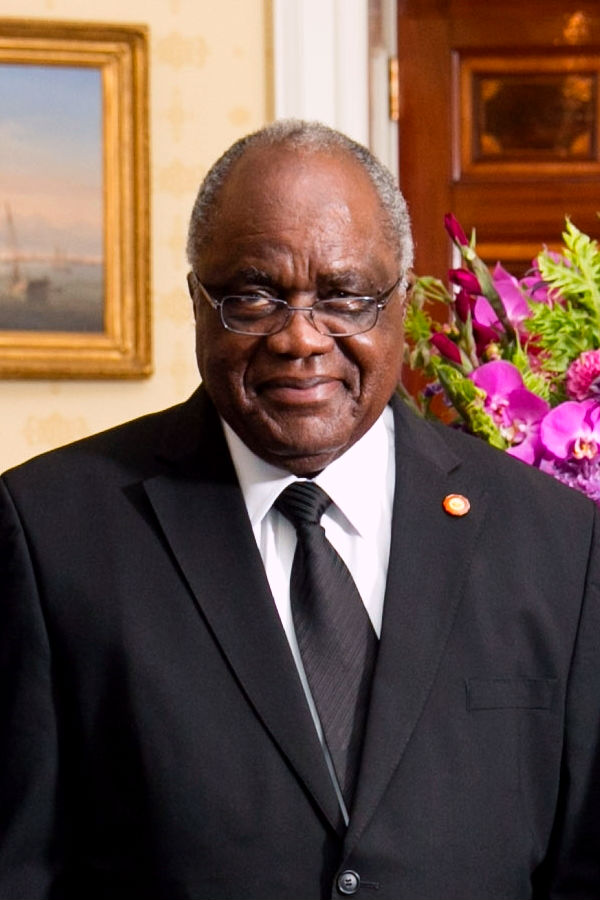

L to R: Blaise Compaoré, Yoweri Museveni, Pierre Nkurunziza, and Robert Mugabe sought to extend or circumvent term limits in their countries. Photos: US State Dept., UK Foreign Office, World Economic Forum, and US Navy/Jesse B. Awalt.

In recent years, African politics have been marked by increasing numbers of leaders seeking to evade presidential term limits in order to extend their stays in office. These moves not only compromise national constitutions, but they also often trigger instability and conflict. While incumbents may argue that term limits are incompatible with African realities, this reasoning ignores African-led initiatives and institutions that demonstrate the opposite to be true.

The African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance, ratified in 2012, calls on member states to “entrench a political culture of change of power.” It also identifies “illegal means of accessing or maintaining power,” including “any refusal to relinquish power after free, fair, and transparent elections,” and “any constitutional amendment which infringes the principles of democratic changes of power.”

These principles build on the 2002 African Union (AU) Declaration on the Principles Governing Democratic Elections in Africa, which demands that elections be organized by “impartial, all-inclusive, competent, and accountable national electoral bodies.” It also calls on member states to prevent fraud, rigging, and other illegal practices. In turn, this explicit focus on ethical leadership invokes the 1991 AU/Organization of African Unity (OAU) Conference on Security, Development, and Cooperation in Africa that identified the lack of inclusive democracy as the primary cause of insecurity on the continent.

“[Extending terms] entrenches corruption networks and inequality. … Long-serving leaders are deceiving themselves if they believe that they are doing good for their citizens’ livelihoods.”

Further, today African scholars increasingly argue that there is a direct link between adherence to democratic constitutional frameworks and stability. According to Shola Omotola, a senior lecturer at Redeemer’s University in Nigeria, term limit extensions violate the 2000 Framework for an OAU Response to Unconstitutional Changes of Government. First, they entail the manipulation of constitutional provisions, which in turn violates specific principles of the 2012 Charter. Second, they spark political tensions that often degenerate into violence. Indeed the AU’s Peace and Security Council recognized that “reviews of constitutions to serve narrow interests … are potent triggers for popular uprisings.” The late Mwangi Kimenyi, former director of the Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution, noted that extending terms “entrenches corruption networks and inequality. … Long-serving leaders are deceiving themselves if they believe that they are doing good for their citizens’ livelihoods,” he warned. Other observers, such as Jideofor Adibe, a senior lecturer at Nasarawa State University in Nigeria, go further, arguing that such moves amount to “constitutional coups,” which are just as damaging as military coups, their democratic rhetoric notwithstanding.

Varied and sophisticated techniques

Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni in 2005 offered a “political sweetener” by combining the scrapping of term limits with the promise of a return to multiparty democracy. The two proposals were tabled together, putting opponents in an awkward position since opposing the term limit removal would have also resulted in rejecting the reintroduction of multiparty politics.

The use of formal institutional channels, as opposed to extraconstitutional means, has become a common technique used for extending incumbency. Invoking democratic and pan-Africanist rhetoric imparts an aura of credibility and the appearance of commitment to the democratic process. In almost all such cases, incumbents exploit loopholes to extend their terms in office. With strong parliamentary majorities buttressed by extensive systems of patronage, leaders are able to change constitutional provisions and manipulate elections.

Sylvère Nimpagaritse, formerly Vice President of Burundi’s Constitutional Court.

The maneuvers incumbents deploy differ depending on the context. Namibia’s founding president, Sam Nujoma, kicked off the trend in 1998 by introducing a bill allowing him to serve a third term. The effort was framed around a narrow and technical reading of the Namibian constitution, which argued that since the president had first been elected by a Constituent Assembly his first term did not count toward the limit. (Nujoma declined to run for a fourth term and stepped down in 2005.) Zambia and Malawi followed suit in 2001 and 2003 respectively. However, the incumbents there, Frederick Chiluba and Bakili Muluzi, failed to secure their bids after their riotous parties split and lost their parliamentary majorities. In Chad, Guinea, and Niger, incumbents were unsure about whether their parliaments would acquiesce to a constitutional change despite enjoying strong majorities. All three opted instead for referenda; all three succeeded.

Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni in 2005 offered a “political sweetener” by combining the scrapping of term limits with the promise of a return to multiparty democracy. The two proposals were tabled together, putting opponents in an awkward position since opposing the term limit removal would have also resulted in rejecting the reintroduction of multiparty politics. Last year in Burundi, the ruling party has used a technical loophole to reinterpret the 2010 Constitution and its founding document, the 2000 Arusha Accords, to extend President Pierre Nkurunziza’s stay in office. Party supporters argued that since the President had been elected by a parliamentary vote in 2005, his first term did not meet the universal suffrage test. Today, the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Joseph Kabila is believed to be seeking an extension by default when his term expires in November 2016. His party has introduced a raft of laws that observers and opponents say will inevitably delay the elections and allow him to invoke a provision allowing him to remain in office until all outstanding laws have been passed—which could mean indefinitely.

Tactics and lessons for constitutional norms

Hifikepunye Pohamba respected Namibia’s two-term limit and ceded power to his successor in 2015.

A 2015 Afrobarometer study across 30 countries found that the overwhelming majority of Africans favor limiting presidential mandates to two terms. This is the majority view even in countries that have never had term limits or have removed them, which puts into question the claim by incumbents that their campaigns reflect popular demands. On the contrary, resistance to term limit changes is growing. In Namibia, popular discourse on constitutionalism expanded in the aftermath of Nujoma’s third term, thanks to a vigilant and well organized civil society. Nujoma’s successor Hifikepunye Pohamba, respected the two-term limit and handed the government’s reins over to his successor, Hage Geingob, in 2015.

In Malawi and Zambia, ruling party reformists forged strategic alliances with the opposition and civil society to block constitutional amendments extending presidential term limits. In Burundi, similar amendments were narrowly defeated in March 2014 by an informal alliance of ruling party and opposition lawmakers and a coalition of over 200 civic associations. This alliance also went on to defeat the government’s attempt to put the matter to a referendum. But the ruling party pressed on with its bid anyway, prompting 100 high-ranking members of its cadre to leave in protest. The party put its case before the Constitutional Court, but a day before the ruling the court’s Vice President fled, citing intimidation. The government again pushed ahead, triggering widespread riots and eventually an armed rebellion.

Protesters in Burkina Faso. Photo: Z. Wanogo/VOA.

In Burkina Faso, opposition parties and civil society groups held year-long civil disobedience campaigns in 2014 to protest the president’s third-term bid. The climax came on October 30 after parliament passed a bill paving the way for a referendum. Riots intensified on October 31, and a takeover by the military followed, sending President Blaise Compaoré into exile. Power was subsequently transferred to the speaker of the National Assembly, followed by the establishment of a transitional government.

While these struggles continue, so too do attempts by incumbents to extend or sidestep term limits. Courts, parliaments, and referenda offer formal, albeit manipulated, avenues for incumbents to legitimize their actions by invoking the democratic process. However, opposition to such moves is now deeply embodied in narratives of resistance as an outlet for citizens’ grievances. Importantly, as seen in the case of Burkina Faso, term-limit advocates are not framing their struggles within the context of Western norms. Rather, it is seen as an African normative framework that is being violated by the continent’s leaders.

Africa Center Experts

- Joseph Siegle, Director of Research

- Dorina Bekoe, Associate Professor, Conflict Prevention, Mitigation, and Resolution

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Africa and the Arab Spring: A New Era of Democratic Expectations,” Special Report 1, November 2011.

- Joseph Siegle, “Overcoming Dilemmas of Democratization: Protecting Civil Liberties and the Right to Democracy,” Nordic Journal of International Law, 2012.

- Joseph Siegle, “Why Term Limits Matter for Africa,” Center for Security Studies blog, July 3, 2015.

- Joseph Siegle, “The Political and Security Crises in Burundi,” testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Africa and Global Health, December 9, 2015.

More on: Democratization African Union Burkina Faso Burundi Governance Malawi Rule of Law Uganda