“The problem we are trying to resolve in Burundi is political and cannot be solved using military means. These [peacekeeping] troops will not solve the crisis but will create an enabling environment to continue the peace talks.”

The date is October 16, 2001, and the speaker is former South African President Nelson Mandela. As mediator of the Arusha peace talks on Burundi, he had just requested his successor, President Thabo Mbeki, to deploy South African forces to support the process. The Burundian government at the time, led by President Pierre Buyoya, was strongly opposed to such a force stating: “Burundians are not happy with this decision and will never accept it.” The idea of deploying a neutral force into Burundi had been mooted several years earlier by the former mediator, retired Tanzanian President Mwalimu Julius Nyerere who like Mandela, argued that: “Military intervention will not solve the problem but you cannot rule it out because killings and assassinations are going on and with the people absolutely frightened we cannot sit and let them continue.”

Despite the Burundian government’s resistance, Pretoria on October 30, 2001, deployed the South African Protection Service Detachment (SAPSD) to Burundi to protect exiles returning to negotiate the final stages of the peace talks. In 2003, as ceasefire talks gained momentum, the African Union, deployed the African Mission to Burundi (AMIB), mostly comprising South African, Ethiopian, and Mozambican troops to provide civilian protection, among other tasks. AMIB was later “rehatted” as the United Nations Mission to Burundi (ONUB), with South African Special Forces staying on as a separate African Union Specialist Task Force (AUSTF) until 2007. These deployments enabled the return of exiles to negotiate the final status talks, provided protection to civilians, created confidence for the return of refugees and assisted the implementation of transitional arrangements, including disarmament and military reform.

Despite the Burundian government’s resistance, Pretoria on October 30, 2001, deployed the South African Protection Service Detachment (SAPSD) to Burundi to protect exiles returning to negotiate the final stages of the peace talks. In 2003, as ceasefire talks gained momentum, the African Union, deployed the African Mission to Burundi (AMIB), mostly comprising South African, Ethiopian, and Mozambican troops to provide civilian protection, among other tasks. AMIB was later “rehatted” as the United Nations Mission to Burundi (ONUB), with South African Special Forces staying on as a separate African Union Specialist Task Force (AUSTF) until 2007. These deployments enabled the return of exiles to negotiate the final status talks, provided protection to civilians, created confidence for the return of refugees and assisted the implementation of transitional arrangements, including disarmament and military reform.

Fifteen years on, posturing by another Burundian government to forestall an African protection force is once again on display. In response to the sharp escalation of violence on December 12, 2015, the African Union (AU) committed to deploy the African Prevention and Protection Mission in Burundi (MAPROBU) to protect civilians in imminent danger and create conditions for political dialogue. This action was taken after Burundian government forces conducted violent reprisals in opposition neighborhoods following coordinated rebel attacks on several military bases. The Burundian authorities put the day’s death toll at 87. Unofficial estimates indicate that the number of killed was much higher. Human rights monitors documented extrajudicial executions, arbitrary arrests, looting, and numerous bodies in the streets – many shot with a single bullet to the head and some with hands tied behind their backs. The vast majority of those targeted were Tutsis, according to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. The United Nations, in early January 2016, announced that it was analyzing satellite images to investigate witness reports of at least nine mass graves including one in a military camp, containing more than 100 bodies.

In response to the AU announcement on MAPROBU, Burundi’s president warned on December 30 that: “We don’t need them … everybody should respect Burundi’s borders … if they don’t, they will have attacked Burundi and Burundians must stand up and fight them.” Peace talks that had been scheduled to resume on January 6, 2016 in Tanzania, did not get underway as the government cited disagreements over the date and the composition of the opposition and civil society delegations. On January 7, Tanzanian Foreign Minister Augustine Mahiga called for a speedy resumption of the talks as the “only way to stop the bloodshed.”

Reacting to the Burundi government’s resistance to MAPROBU he said: “Burundi has taken a position which isn’t based on a true understanding of this force.” He explained, “Its purpose is to protect the people … secure safe space for dialogue, assist with disarmament and protect vital installations.” Ugandan minister of defense and facilitator of the peace talks, Dr. Chrispus Kiyonga, said: “Shooting at AU peacekeepers would be a grave mistake,” adding, “we are all bound by AU decisions … if one is not satisfied they can challenge it through proper channels.”

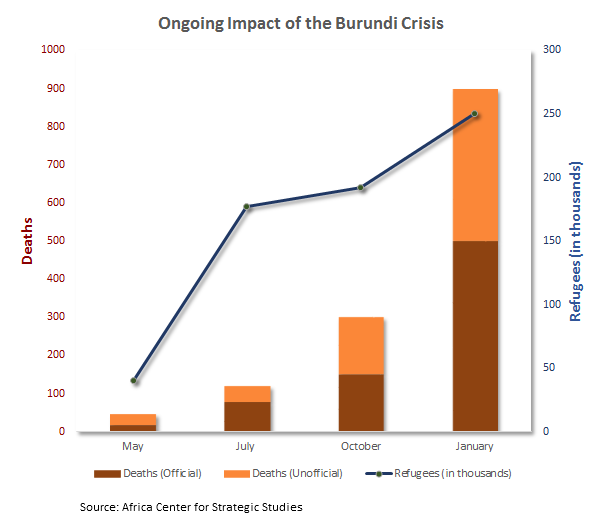

Delays in diplomacy—and a crisis accelerates

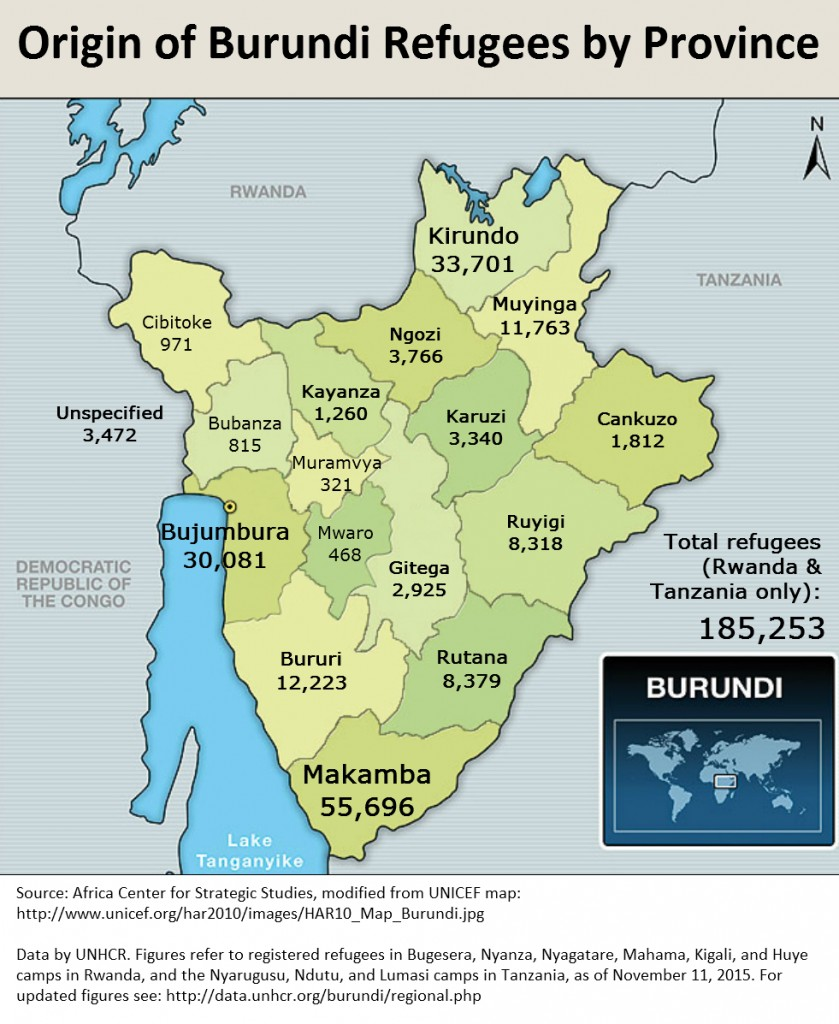

The crisis was triggered in April by President Pierre Nkurunziza’s decision to run for a third term which opponents say violates the terms of the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement of 2000, the blueprint that ended a brutal 12 year civil war and cycles of deadly violence including mass killings and genocide. When mediation got underway in mid-May under the auspices of the East African Community (EAC), the death toll stood at 18 and 40,000 people had fled as refugees. EAC mediator, Ugandan President, Yoweri Museveni, tried unsuccessfully to secure an agreement ahead of elections scheduled for July. The polls went ahead, which neither the AU nor the EAC recognized as credible. In the immediate aftermath of the fraught elections the death toll stood at 77, with some 500 wounded. The number of refugees had risen to 177,000.

Corresponding with this increase in fatalities and refugees was a shift in the patterns of violence. A week before the polls, clashes between government forces and rebels took place in northern Burundi in guerilla-style attacks claimed by Burundian officers who had defected from the army. In early August the most feared military figure and key ally to Nkurunziza, General Adolphe Nshimirimana, was killed in a well-coordinated rocket attack. A day later, a leading civil society leader, Pierre Claver Mbonimpa, was shot in the face at point blank range and rushed overseas for treatment. Days later, Come Harerimana, a local leader of the ruling CNDD/FDD, was pulled from his motorcycle and killed. Regime loyalists retaliated on August 15, when ex-army chief of staff, Col. Jean Bikomagu, was gunned down in front of his house. Three days later four CNDD/FDD members were killed in a bar in Bujumbura’s Musaga neighborhood. On August 23 Pontien Baratwanayo, a local administrator from the opposition FNL, was shot dead.

These tit-for-tat killings escalated over the next several months as several dozen police and intelligence officers as well as civil society and opposition activists were either killed or targeted. In early September, Army Chief of Staff General Prime Niyongabo narrowly survived a well-coordinated attack on his convoy as he drove to work. By the end of that month, the International Organization for Migration reported that 192,000 refugees had been registered. The official death toll had risen to 150, and, over 700 had been arrested. November saw an uptick in tension as a new wave of refugees fled the country ahead of a major security operation to flush out weapons. This operation coincided with a November 3 speech by the Senate President, Reverien Ndikuriyo, that incited ethnically-based violence: “You tell those who want to execute the mission: on this issue, you have to pulverize, you have to exterminate – these people are only good for dying. I give you this order, go!” In the wave of deaths that occurred between November 6 and 8 when the operation was carried out, civil society leader Claver Mbonimpa’s son was among those killed. By the end of the month the number of refugees had swelled to 216,000. On November 12, the UN Security Council responded by calling for an urgent resumption of dialogue to find a solution. This reinforced an October 17 AU decision to expedite contingency planning for the deployment of an African-led peacekeeping mission to prevent further violence.

As of mid-January 2016, the official death toll stood at 500, but unofficial estimates indicate that as many as 900 people had died and the number of refugees had risen to nearly 250,000, the vast majority of them women and children.

Risks of greater instability

If it maintains its current trajectory, all indications are that the security conditions in Burundi will continue to deteriorate at an escalating rate. Factors likely to contribute to this trend include:

- Ethnically-based incendiary language is being increasingly invoked by government leaders raising fears that the stage for more violence is being set. While Burundians have thus far not been receptive to ethnic-based incitement, fears are that ethnic polarization will overwhelm community resiliencies and may lead to a repeat of Burundi’s history of mass killings and genocide.

- Doubts about the government’s sincerity and willingness to engage in dialogue are strong. A significant segment of Burundians have concluded that the only pressure Nkurunziza will respond to is force. Since mid-July numerous rebel groups have formed and as many as 60 battle-related incidents between government and rebel forces have been recorded including a mortar attack on the presidential palace in mid-November. Deepening the crisis further is the emergence of armed vigilantes in some of the neighborhoods hardest hit by the violence. Formed by youth who say “we decided to do this to protect ourselves,” these groups add to a combustible mix of pro and anti-government militias that will be difficult to rein in if the situation continues to deteriorate and no effective response is forthcoming.

- Divisions in the military are growing. A wave of desertions occurred in the aftermath of a failed coup attempt in May, with about 150 officers and enlisted men from the 11th Armor Battalion and 121st Parachute Battalion going into exile or rebellion. Attrition among key officers has continued since. In October, officers from the elite 17th Battalion (including its deputy commander) and the Logistics Brigade, left the force with about 120 officers and enlisted men, weapons, and communications equipment.After the coup, the government has undertaken purges of those in the military seen as insufficiently loyal. This has fueled distrust in one of the institutions that is seen as having made genuine progress in advancing the multi-ethnic spirit of the Arusha Accord. The force is composed equally of soldiers of the ex-Armed forces of Burundi (ex-FAB), which are predominantly Tutsi, and militiamen of the majority Hutu rebel groups that fought against successive Tutsi-led governments. The Nkurunziza government’s reprisals following the coup attempt have mostly targeted the ex-FAB. However certain former rebels have not been spared either. The government operates via parallel chains of command over which it maintains political and ethnic control. Accordingly, while the military has largely remained politically neutral during the crisis, pressure to demonstrate party and ethnic loyalties can be expected to take a toll on military professionalism. This can only fuel more instability.

MAPROBU

Threats by the Nkurunziza government have raised questions over the deployment of the African Prevention and Protection Mission in Burundi (MAPROBU). While all scenarios should be taken into account, the likelihood and effectiveness of such retaliation remains open to question. First, it is unlikely that members of the Burundian army, degraded as it is, would risk jeopardizing their continued participation in AU missions. Second, while regime-aligned militias such as the Imbonerakure (the government-supported youth militia), hold the balance of strength over unarmed civilians, it is unlikely they would be able to stand up to organized forces. Third, the strategic controversy that would be created by an AU member state firing on African forces is one that cannot be ignored.

It should also be recalled that the decision to deploy MAPROBU was not solely based on the realities within Burundi but for the benefit of the entire Great Lakes region. If Burundi continues on its path of escalating conflict this will have destabilizing effects on all of its neighbors. The need for preventative deployments to avoid mass atrocities and extended conflicts, moreover, has been a compelling driver behind the creation of the AU’s African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). Should Burundi descend into another full-scale civil war absent the deployment of MAPROBU, the credibility and indeed rationale for the entire APSA project will be thrown into question.

It should also be recalled that the decision to deploy MAPROBU was not solely based on the realities within Burundi but for the benefit of the entire Great Lakes region. If Burundi continues on its path of escalating conflict this will have destabilizing effects on all of its neighbors. The need for preventative deployments to avoid mass atrocities and extended conflicts, moreover, has been a compelling driver behind the creation of the AU’s African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). Should Burundi descend into another full-scale civil war absent the deployment of MAPROBU, the credibility and indeed rationale for the entire APSA project will be thrown into question.

As Nelson Mandela and Julius Nyerere observed, deployment of regional troops in Burundi is not a solution on its own. However, as during previous crises in Burundi, it may be an indispensable step to create an enabling environment for meaningful peace talks to move forward.

Additional Resources

- Emma Svensson, “The African Mission in Burundi (AMIB): Lessons from the African Union’s First Peace Operation,” Swedish Defense Research Agency, 2008.

- African Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), “South Africa’s Peacekeeping Role in Burundi: Challenges and Opportunities for Future Peace Missions,” Occasional Paper Series, Volume 2, Number 2, 2007.

- Joseph Siegle, “The Political and Security Crises in Burundi,” Testimony before the United States Senate Foreign Relations Committee, December 9, 2015.

- Cedric de Coning, Walter Lotze and Andreas Øien Stensland, “Mission Wide Strategies for the Protection of Civilians: A Comparison of MONUC, UNAMID and UNMIS,” Norwegian Institute for International Affairs, Security in Practice, Working Paper No 792, 2011.

- Cedric de Coning, Walter Lotze, Zinurine Alghali and Lamii Kromah, “Report of the Workshop on Mission-Wide Protection Strategies on the Protection of Civilians in United Nations Peacekeeping Operations,” African Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes, June 1, 2010.

More on: Peacekeeping Burundi Ethnic Conflict Leadership