Following its “year of elections” in 2024, when 19 African countries were slated to hold elections to select their head of state, Africa’s roster of 2025 elections is more modest, with 10 polls on tap.

Credibility will be a key theme for this year’s elections, with half of the planned polls shaping up to be highly orchestrated processes with the predictable outcome of a victorious incumbent. This, in fact, has been a recurring theme in recent years. Of the elections planned last year, five were not even held, due to the incumbents’ sense of impunity to uphold democratic institutions and the rule of law.

Credibility will be a key theme for this year’s elections, with half of the planned polls shaping up to be highly orchestrated processes

The limited credibility of some of these electoral processes is not occurring in isolation but rather is part of a concerted effort by certain incumbents or ruling parties to further insulate themselves from the public will—and popular accountability. This is effected through an increasingly shrewd series of tactics including term limit evasions, extending presidential terms, weakening of constitutional courts, and usurping the independence of election management bodies, among other means of eroding democratic checks and balances.

A preponderance of this year’s elections will be in Francophone countries with seven of the ten occurring in West and Central Africa—the epicenter of Russian influence operations to undermine democracy on the continent.

An imperative for policymakers, journalists, and analysts will be to apply a sufficiently sophisticated lens in interpreting these electoral processes.

An imperative for policymakers, journalists, and analysts will be to apply a sufficiently sophisticated lens in interpreting these electoral processes. These analyses will need to differentiate between genuinely competitive elections where citizens can freely express themselves and those electoral exercises that employ the trappings of an election but where actual participation—and thus the outcome—are tightly controlled. Absent such differentiations, there will be limited incentives for incumbents to do more than go through the motions. At stake is the bar for democratic norms on the continent.

For countries with competitive elections, the process will provide an occasion for the public to validate their support for the direction of the country—as well as the opportunity for democratic self-correction and renewal.

All but two of the planned 2025 elections fall in the final third of the year, leading to a busy end of year election season. The long lead up will provide an opportunity to further scrutinize the issues driving each election—and their implications for democratic development.

Following are key issues to watch.

| Country | Type of Election | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Togo | Senatorial | February 15 |

| Gabon | Presidential and Legislative | April 12 |

| Malawi | Presidential and Legislative | September 16 |

| Seychelles | Presidential and Legislative | September 27 |

| Guinea | Presidential and Legislative | September-October |

| Cameroon | Presidential | October |

| Côte d'Ivoire | Presidential | October |

| Tanzania | Presidential and Legislative | October |

| Guinea-Bissau | Presidential | November 30 |

| Central African Republic | Presidential and Legislative | December |

In addition, there are five countries that will have legislative elections this year: Comoros (January 12), Burundi (June 5), Guinea-Bissau (November), Equatorial Guinea (November), Egypt (2025), Tunisia (2025).

Togo

Togo

Parliamentary, February 15

View this section as separate page

For all practical purposes, Togo’s 2025 presidential elections were held in March 2024 when lawmakers in the National Assembly, dominated by the ruling Union pour la République (UNIR) party, voted 87-0 to adopt a constitutional change that eliminates citizens’ right to vote directly for the country’s leader.

The result has been to create an uncontested path for President Faure Gnassingbé to extend his 20-year hold on power—and perpetuate the 58-year family dynasty over this coastal West African country of 9.3 million people.

For all practical purposes, Togo’s 2025 presidential elections were held in March 2024 when lawmakers eliminated citizens’ right to vote directly for the country’s leader.

The revised constitution establishes a new powerful executive position of President of the Council of Ministers (PCM). Elected by the National Assembly, the role will function as a prime minister with full decision-making and civil and military authority for the government. The PCM will come from the party with the most seats in the National Assembly. One-sided legislative elections hurriedly held the month after the constitutional revision gave the UNIR 108 of the 113 National Assembly seats, setting up Gnassingbé to be the first PCM.

The February 2025 elections will be for senatorial positions that create a new upper chamber to Togo’s legislature. Two-thirds of these seats will be elected by local authority representatives and one-third will be appointed directly by the PCM.

The PCM position will have a 6-year term—compared to the 5 years of the current presidency—and is renewable indefinitely. This is significant in that the adoption of a two-term presidential limit has been a focal point of political debate in Togo for years in the effort by the opposition to establish a finite duration to the Gnassingbé dynasty. The term limit issue sparked mass protests across the country until the term limit provision was included in the 2019 Constitution.

A police Armored Personnel Carrier is parked in front of a campaign billboard for President Faure Gnassingbe, candidate of the ruling Union for the Republic (UNIR) party. (Photo: AFP/Pius Utomi Ekpei)

The removal of citizens’ rights to universal suffrage (and the term limits requirement), paradoxically, was not taken through a popular referendum but rather by the March 2024 legislative action by the ruling party. The text of the changes had not even been made public prior to the vote.

Efforts by the opposition to mobilize protests against the UNIR’s constitutional chicanery were blocked by the government. Even the Catholic Church, which plays a vital role in Togolese society, was prevented from observing the April 2024 National Assembly elections.

The UNIR was able to push through these changes due to its near monopoly of the National Assembly as a result of widespread irregularities in previous elections that had led to an opposition boycott. This controversial vote tallying included the 2020 presidential election, in which the opposition is widely believed to have gained a plurality of votes. In 2015, the opposition received more than 40 percent of the official vote.

Political rallies have been banned in Togo since 2022.

The UNIR aims to use this bureaucratic sleight-of-hand to institutionalize its political dominance without an electoral mandate. It also intends to insulate Gnassingbé from further challenges to his serial evasion of term limits, providing a mechanism for him to remain in power for life.

To further remove popular participation from the political process, political rallies have been banned in Togo since 2022.

The two largest opposition parties have indicated that they will boycott the senatorial elections. The l’Alliance nationale pour le changement (ANC), a leading opposition party, has announced it will not participate, calling the elections a “masquerade” and criticizing the previous legislative and regional elections for being marred by fraud and irregularities. This sentiment was echoed by the opposition coalition, Dynamique pour la Majorité du Peuple (DMP), which described the senatorial elections as part of an ongoing “constitutional coup d’état.”

Togo’s police and army are seen as closely aligned with the ruling UNIR party. The army was instrumental in ensuring that Faure Gnassignbé succeeded his father, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, when he died in office in 2005. Security actors’ response to protests in 2005 left hundreds dead. Violent police crackdowns on political demonstrations have continued under Faure Gnassingbé’s rule. A distinctive feature of Togo’s military is that 70 percent of its members are from Gnassingbé’s Kabye ethnic group, even though the tribe makes up only 13 percent of the population.

A man walks an elder to a polling station at the Agbalepedogan public primary school in Lomé. (Photo: AFP/Emile Kouton)

Togo’s entrenched dominant-party model has exacted heavy costs on its population. The poverty rate is 45 percent and real per capita incomes are less than $900 per year, leaving Togo as one of the poorest countries in the region. With government debt of 68 percent of gross domestic product and limited foreign direct investment, employment and development have been lackluster, exacerbating inequality.

The military’s focus on politics has been a distraction from its primary mission of protecting civilians—an issue of growing concern with the deepening militant Islamist insurgency in Burkina Faso that is increasingly spilling over the border and threatening to trigger wider instability in northern Togo.

The 2025 “elections” are thus the culmination of a years-long strategy to unwind Togo’s fledgling democratic institutions. In the process, the UNIR is also removing the legal means to exercise basic rights of expression, assembly, and suffrage. While this may seem like a political victory for the UNIR, these actions are likely setting the country on a path toward greater instability.

Gabon

Gabon

Presidential and Legislative, April 12

View this section as separate page

The Gabon presidential election is shaping up to be a highly orchestrated exercise aimed at conferring a degree of legitimacy on the military regime of Brigadier General Brice Oligui Nguema who seized power in a coup on August 30, 2023.

Gabon is on track to swap one form of autocratic governance with another.

Oligui has followed a carefully choreographed sequence of actions to pave an unobstructed pathway to claim the presidency in this resource-rich country of 2.5 million people within the vital Congo Basin region. This includes declaring himself Transition President on September 4, 2023, appointing loyalists to two-thirds of the Senate and National Assembly, naming all 9 members of the Constitutional Court, and hosting a tightly scripted national dialogue in mid-2024, from which 200 political parties were banned and in which the military played a prominent role.

An outcome of the proceedings was the rewriting of the constitution to allow members of the military to contest political office, remove the role of the prime minister, extend presidential terms to seven years, and abolish the two round electoral system (thus lowering the threshold of popular support needed), transfer of responsibility for overseeing the elections from the electoral commission to the Ministry of Interior, and adopt a strict electoral code to limit potential presidential candidates.

Each of these changes further consolidates authority within Gabon’s already highly centralized executive branch while also providing Oligui a glide path to extend his hold on power. These changes were subsequently validated in a perfunctory constitutional referendum in November 2024.

Gabon Republican Guard seizes power in 2023. (Photo: screenshot from “Pressure Mounts on Gabon Junta to Relinquish Power After Coup”)

On March 4, 2025, Oligui announced his candidacy for president as an independent candidate.

Oligui appears to be replicating the coup transition playbook of General Mahamat Déby of Chad who ignored the constitutionally mandated succession process to seize power in April 2021, declare himself president of the transition, host a stage-managed national dialogue, and hold a flawed constitutional referendum that opened the door for him to declare victory in a predictable presidential election in May 2024.

Oligui has cultivated the image of a reformer playing off the popular revulsion toward the profligacy and repression of the government of Ali Bongo and the Bongo family dynasty that had ruled Gabon for 56 years. This obscures the reality that Oligui has been a longtime confidant of the Bongo family. He is a cousin of Ali Bongo and served as aide-de-camp to Omar Bongo until his death in 2009. He was head of intelligence services for the Republican Guard before being appointed by Ali Bongo to lead the Guard in 2020. The force size and budget of the Republican Guard grew significantly under Oligui—providing him the platform from which to launch his coup. Oligui is likewise reported to have accumulated considerable wealth from his close ties to the Bongos.

Oligui has cultivated the image of a reformer but he has been a longtime confidant of the Bongo family.

Oligui, thus, is in many ways a continuation rather than a departure from the Bongo dynasty. His extraconstitutional seizure of power is also a warning of the risks of a politicized military that becomes so integral to keeping an autocratic regime in power that the barriers to the military taking the final step of assuming power itself becomes increasingly extraneous.

Overlooked in the coup and the subsequent managed transition is that there is an organized civilian opposition that has been vigorously contesting recent elections in Gabon despite the lopsided playing field. An opposition coalition, Alternance 2023, led by former university professor Albert Ondo Ossa, promoted a reform agenda for Gabon during the 2023 elections aimed at redressing the patronage-driven inequity that has characterized the country and has resulted in an estimated 40 percent of youth unemployment despite Gabon’s oil wealth and $9,000 per capita income (one of the highest in Africa).

An election official burns ballots after the counting has finished at a voting station in Libreville on November 16, 2024. (Photo: AFP/Nao Mukadi)

Ossa is widely believed to have won the 2023 elections despite widespread irregularities, the absence of international monitors, the arrests of local election monitors, and an internet ban in the final month of the campaign. Official results reported Ossa earning 31 percent of the vote to Ali Bongo’s 64 percent. The incredulity of Bongo’s claim of victory provided the backdrop for Oligui’s coup. Rather than calling for an independent review of the vote count to acknowledge the rightful winner, however, Oligui moved to have himself installed as transitional president.

Overlooked in the coup and the subsequent managed transition is that there is an organized civilian opposition.

Opposition leaders have subsequently challenged Oligui’s authority to rewrite the constitution and electoral code that enables his pathway to the presidency in 2025.

Despite the unlevel playing field, 22 opposition leaders submitted their candidacies to the Ministry of Interior. Only seven of these were accepted, however. Opposition candidates with the most name recognition, like Albert Ossa and Pierre Moussavou, were barred from contesting due to the age limit (of 70 years) inserted in the new electoral code. Others were prohibited from running due to inadequate parental citizenship and marriage certificate documentation.

Among the candidates deemed eligible, Alain-Claude Bilie-By-Nze, a former Prime Minister and head of the Gabonese Democratic Party, is regarded as the most formidable opponent. Over the past year, Bilie-By-Nze has positioned himself as a critic of the transitional government, voicing concerns about the former ruling party, the military regime’s revision of the constitution, and the lack of representation in the national dialogue process. Iloko Boussengui Stéphane Germain, a former ally of Bilie-By-Nze, will also contest in the election, sparking speculation of a possible deal with the military regime as a means to dilute the opposition vote count in the single round, first-past-the-post election.

To further stifle dissent, any criticisms that the military is exploiting the transition process for its political gain are branded by state-run media as antipatriotic

Other opposition parties, including the former ruling party and the National Union Party, have either assumed leadership roles or endorsed Oligui.

Given the legacy of vote rigging in Gabon and the tightly structured post-coup transition, prospects of a free and fair process are dim. To further stifle dissent, any criticisms that the military is exploiting the transition process for its political gain are branded by state-run media as antipatriotic and undermining of national unity. Oligui has also used military recruitment to build support, announcing in December 2024 that thousands of youth would be recruited into the armed forces.

Listening for the preferences of the muffled civil society voices who have been the champions for democratic reform in Gabon over the years may be the most illuminating aspect of an otherwise foreseeable electoral process that is on track to swap one form of autocratic governance with another.

Malawi

Malawi

Presidential, September 16

View this section as separate page

The preeminent issue driving Malawi’s presidential election is the economy. Malawi has been particularly hard hit by the severe El Niño-induced drought that impacted southern Africa in 2024. As Malawi is a land-locked country with 80 percent of its population living in rural areas, the drought has had the compounding effect of spiking unemployment. These hardships have been exacerbated by food price inflation of over 20 percent. As a result, a quarter of Malawi’s 23 million citizens are facing acute food insecurity.

Malawi’s economic woes directly impact President Lazarus Chakwera’s campaign, who as leader of the Malawian Congress Party is contesting for a second term in office. Chakwera is being challenged by two former presidents: 84-year-old Peter Mutharika (of the Democratic Progressive Party), whom Chakwera defeated in the 2020 presidential contest, and 74-year-old Joyce Banda (of the People’s Party), who was president from 2012 to 2014. While each candidate can tout their executive experience, each is burdened by links to previous bouts of economic turmoil and allegations of corruption.

Key issues to watch in Malawi’s 2025 elections will be the resiliency of Malawi’s civic institutions and courts to ensure a fair process.

With the requirement that a winning candidate must secure more than 50 percent of the vote, there is a strong possibility the election will go to a second round. Reaching this threshold will likely entail coalition building among other parties. This may elevate the leverage smaller parties, such as the United Transformation Movement (UTM) and the United Democratic Front, to shift the focus of the campaign away from the personalities and politics of the established parties and toward fresh proposals to address Malawi’s acute economic challenges. The UTM is still recovering from the death of its founder, Vice President Saulos Chilima, in a plane crash in June 2024. Chilima had a particularly strong following among Malawi’s youth.

Moving the debate to substantive issues is particularly relevant given the structural dimensions of many of Malawi’s challenges, which transcend any one administration. Prime among these is corruption. With a Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index ranking of 115 out of 180 countries, Malawi is far from the most egregious African country in this regard. However, the pervasiveness of patronage directly impacts public services and job creation—and public trust. With an annual per capita income of $463, this misallocation of resources is particularly damaging.

The pervasiveness of patronage directly impacts public services, job creation, and public trust.

Malawi’s Anti-Corruption Bureau (ACB) has been operational since 1998 and, in recent years, had gained more independence from political influences. In the 3-year tenure of Director General Martha Chizuma, a record high 119 cases were investigated, including against high-profile politicians, often involving bribery and procurement fraud. Cutting too close to home for some senior officials, however, Chizuma faced numerous institutional obstacles before finally resigning in 2024 after the ACB was starved of funds. A central campaign theme of interest to Malawian citizens, then, will be how the ACB and other anticorruption bodies can be further empowered.

Another priority campaign theme is sustainable economic diversification. Given its heavy reliance on rain-fed agriculture for livelihoods, Malawi is particularly susceptible to variations in the weather. Home to one of Africa’s most youthful populations, with a median age of 17.8 years, Malawi’s population has nearly doubled in the past 20 years. Unless enough jobs can be created, Malawi is vulnerable to higher levels of petty and organized crime.

Malawi’s demographic pressures are resulting in ever smaller farm sizes and a 21-percent decline in its forests since 2022. The loss of forests, in turn, is contributing to declining soil fertility, biodiversity, and water retention. With 89 percent of Malawians lacking electricity, the demand for charcoal as an energy source puts further pressure on these land resources. The tree cover loss is leaving the country increasingly vulnerable to the devastation of cyclones—as seen by recent storms Idai and Freddy—and the growing prevalence of these intense weather events.

Malawi Electoral Commission staff, accredited civil society organisations, members of the public, and members of the Malawi Defense Forces military band march in Lilongwe to mark the official beginning of the electoral period ahead of the 2025 Malawi General Elections. (Photo: AFP/Amos Gumulira)

The strains of the election campaign have already led to criticism over the impartiality of the Malawian Electoral Commission and the efforts to register new voters. However, Malawi’s Constitutional Court has a reputation for independence with its precedent-setting rejection of the 2019 presidential election results that claimed a victory for the then-incumbent, Mutharika, prompting a rerun that led to a successful outcome for the Chakwera coalition.

Malawi also benefits from a vibrant civic identity and resilient civil society that is consistently demanding higher levels of transparency, respect for the rule of law, and holding politicians accountable. Malawi, furthermore, maintains an active independent media, support for which has been strengthened under the Chakwera administration. Illustratively, in 2024, the Malawi Human Rights Commission ruled in favor of access to information requests of the government, and the Malawi Communications Regulatory Authority has allocated more radio frequencies, enhancing broadcasting diversity.

The Malawian military also has a reputation for professionalism and independence.

The Malawian military also has a reputation for professionalism and independence, including when under pressure by the Mutharika government to crackdown on protesters during the 2019 election crisis. Malawi’s security agencies, especially the Malawi Police Service and the Malawi Defence Force, are also working collaboratively to implement an integrated national election security plan.

Key issues to watch in Malawi’s 2025 elections will be the resiliency of Malawi’s civic institutions and courts to ensure a fair process and the effectiveness of reformist coalitions to come together and forge a path forward to address Malawi’s pressing challenges.

Seychelles

Seychelles

Presidential and Legislative, September 27

View this section as separate page

President Wavel Ramkalawan of the Linyon Demokratik Seselwa (LDS) party will be contesting for his second term as this 115-island archipelago nation in the Western Indian Ocean heads to the polls in 2025. A former Anglican priest, Ramkalawan’s victory in the 2020 elections (his sixth try for the presidency) was a watershed moment for the country of 122,000. The United Seychelles party and its predecessor, the Seychelles People’s Progressive Front, had dominated political institutions in Seychelles since a coup by Albert René in 1977 (1 year after independence from Britain). While multiparty politics were introduced in the early 1990s, the United Seychelles maintained majorities in the National Assembly until 2016 and the presidency until 2020.

President Wavel Ramkalawan (R) looks on during his inauguration on October 26, 2020. (Photo: AFP/Rassin Vannier)

Ramkalawan will be facing Dr. Patrick Herminie, this year’s standard bearer of United Seychelles. Herminie served as the Speaker of the National Assembly from 2007 to 2016, and previously was Director General of Primary Health Care at the Ministry of Health.

A focus for both candidates will be on reducing the country’s 23-percent poverty rate and expanding the middle class in a country with a per capita income of over $17,000, the highest in Africa.

While René died in 2019, Seychelles continues to grapple with reverberations from his long stranglehold on power. Crimes committed during the René era, including patronage and torture, became public during a truth and reconciliation process launched in 2018 and culminating in a final report in 2023. The report included calls for reparations to victims, including apologies and monetary compensation.

Investigations into the René era has resulted in arrests in 2021 over allegations of $50 million in money laundering, involving a Seychellois businessman and the United Arab Emirates government. Searches in the case revealed a cache of arms, generating additional arrests, including of a former senior officer of the Seychelles Defence Forces and Sarah Zarqhani René, the wife of the former president. The cases continue to wind their way through the justice system and provide additional backdrop to the 2025 elections.

A focus for both candidates will be on reducing the country’s 23-percent poverty rate.

They also reflect the ongoing efforts to unravel the cronyism that gained traction within state institutions during the country’s long period of one-party rule. This includes elevating standards of transparency. The National Assembly passed an anticorruption law in 2016 that established the Anti-Corruption Commission of Seychelles (ACCS). The law was amended in 2019 to increase the number of ACCS commissioners and strengthen the Commission’s investigative powers and law enforcement provisions. Seychelles was removed from a European Union list of foreign tax havens in 2021, and the country now ranks 20th out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, the highest of any African country, and an eight-place improvement since 2018.

Seychelles has also made strides in building an independent media. Several newspapers exist besides the state-owned daily. A private television station and two radio stations provide programming alongside the state broadcaster. To mitigate political or communal polarization, the country prohibits political parties and religious organizations from operating public radio broadcasts. To provide further safeguards for independent media, the National Assembly decriminalized defamation in 2021, citing reforms undertaken, and enhanced training for journalists. Seychelles ranked first in Africa in the Varieties of Democracy global press freedom index.

Voters queue at a polling station on the main Island of the Seychelles, on October 24, 2020, during the presidential and legislative elections. (Photo: AFP/Rassin Vannier)

Civilian authorities exercise effective control over a small but well-trained and professional security force. The Seychelles Defence Forces (SDF) are comprised of a 300-strong coast guard, which includes an 80-person air wing. In June 2022, the National Assembly gave the SDF the right to enforce domestic law, effectively removing the separation between police and military. This law prompted a petition to the Constitutional Court by human rights groups for its threat to due process and the rule of law—a case that remains under review.

The SDF’s primary focus is disrupting piracy, illicit trafficking networks, and unsanctioned fisheries in Seychelles’ 1-million-km2 exclusive economic zone. Seychelles is an important regional player in the fight against piracy off East Africa, having held more than 17 trials of 142 suspected pirates since 2009.

Seychelles plays a vital role in maintaining open sea-lanes and protecting the marine environment. This places it in the nexus of competing geostrategic interests between China and India.

Given its location in the Western Indian Ocean, Seychelles plays a vital role in maintaining open sea-lanes and protecting the marine environment. This also places it in the nexus of competing geostrategic interests between China and India. India had negotiated an agreement with the previous Seychellois government to establish a naval base on Seychelles’ Assumption Island. The Ramkalawan government has paused this agreement to avoid being pulled into geostrategic rivalries and to consider the environmental impacts. China, meanwhile, has stepped up its diplomatic outreach to each of the region’s island nations—Comoros, Madagascar, Maldives, Mauritius, and Seychelles.

Seychelles’ continued economic dynamism remains closely linked to a stable blue (maritime) economy. Roughly 45 percent of the country’s gross domestic product is tied to tourism. It is therefore vulnerable to external shocks, such as the COVID pandemic that curtailed international travel. The fisheries sector is a second pillar of the economy, which is highly dependent on maintaining the health and biodiversity of the maritime ecosystem. Seychelles is likewise focused on mitigating climate risks that can trigger devastating cyclones, monsoon rains, floods, landslides, and rising sea levels.

As Seychelles prepares for a competitive 2025 election, how the country continues its push for transparency, expands benefits to all citizens, and manages its evolving security threats will be key issues to watch.

Cameroon

Cameroon

Presidential, October

View this section as separate page

On the surface, Cameroon’s 2025 presidential election looks to be a continuation of the unvarying political system in place since President Paul Biya came to power in 1982. Africa’s second longest serving leader (following Teodoro Obiang in Equatorial Guinea), Biya is standing for his eighth presidential term in the October elections. Biya’s extended terms in office are further remarkable in that presidential terms in Cameroon are for 7 years. Biya’s extraordinarily long tenure has been enabled by a constitutional amendment engineered by his party in 2008, abolishing the two-term presidential limit.

Biya’s Rassemblement démocratique du Peuple Camerounais (RDPC) party has held power in this country of 29 million people since independence in 1960, reflecting the dominant party system in place despite the introduction of multiparty elections in 1992.

A young child hanging posters of Cameroonian President Biya on a wall in Yaoundé. (Photo: AFP)

Biya and the RDPC have maintained their stranglehold over Cameroonian politics via their control over all government institutions, including the electoral commission and judiciary. This has resulted in what independent observers have viewed as a series of fraudulent elections, leading opposition parties to boycott the 2020 legislative and municipal elections. Opposition candidate, Maurice Kamto, and over 200 of his supporters were arrested for protesting the controversial 2018 presidential polls. While Kamto was released after 10 months, 41 of his supporters remain behind bars after being sentenced to 7 years in prison. In 2020, the government banned demonstrations.

The 2025 electoral cycle is destined to be an inflection point in this trajectory, however. Now 91 and the world’s oldest head of state, Biya has been in failing health and has been out of public view for extended periods over the past year. This has set off a nervous behind-the-scenes succession battle within the RDPC. Should Biya die or step down while in office, the Cameroonian constitution states the responsibilities of the head of state would transfer to the President of the Senate, Marcel Niat Njifenji. He would be required to organize elections within 20 to 120 days but would be barred from running himself or otherwise modifying the constitution or composition of the government. A longtime member of the RDPC, Njifenji has held the position of President of the Senate since its inception in 2013 and would not be expected to oversee any dramatic changes in policy.

A unified opposition is vital in Cameroon’s single-round plurality system that favors the incumbent.

This electoral cycle may also be different in that 30 parties under Cameroon’s notoriously fractious opposition have agreed to coalesce around Maurice Kamto as head of the Alliance politique pour le changement (APC) coalition. Kamto is running on a campaign of extending health and education services and reducing the acute inequities in Cameroonian society. Kamto officially garnered 14 percent of the votes in the disputed 2018 presidential election. A unified opposition is vital in Cameroon’s single-round plurality system that favors the incumbent.

This election cycle has also been noteworthy for the citizen outreach efforts led by Dr. Enow Abrams Egbe, the chair of the institution responsible for overseeing the elections, Elections Cameroon. He has actively engaged the public in citizen awareness raising about the electoral process, has led a robust voter registration drive that added over 750,000 citizens to the polls, and is seen as having significantly increased the registration of women and youth. This has dovetailed with civil society efforts, some of which have been organized by the Catholic Church, to instill a fervor for civic engagement among Cameroonian youth.

The electoral playing field remains highly uneven.

The electoral playing field remains highly uneven and pliable to RDPC influence, however. An illustration of this is the government’s ban on the two leading opposition coalitions, including the APC, declaring them “illegal” and “clandestine movements.” Kamto may face further hurdles in that his party, having boycotted the last legislative elections, does not hold seats in the current legislature, a prerequisite for a presidential candidate. The ruling RDPC is attempting to exploit this technicality by postponing legislative elections until 2026, even though they are normally held concurrently with the presidential election.

The months leading up to the election have also been marked by an increase in arbitrary arrests, intimidation, and military court trials for opposition party members, journalists, and civil society leaders. This has occurred within a broader crackdown against journalists deemed to be critical of the government. This includes the suspension of media outlets’ licenses and violent attacks and arrests of journalists who have reported on government corruption or mismanagement.

While Cameroon has long been dominated by a single party, the use of repressive tactics has grown in recent years, belying Cameroon’s legacy of inclusivity in line with its rich sociocultural and linguistic diversity. This is most vividly seen by the harsh measures taken to restrict the rights of the English-speaking communities in Northwest and Southwest Regions (comprising 15 to 20 percent of the population) since 2016. The resulting conflict, in which human rights abuses are alleged to have been committed by both sides, has resulted in over 3,000 deaths, nearly 700,000 displaced people, and the interruption in school for roughly 600,000 children. The insecurity and growing alienation of these Anglophone regions will certainly depress voter turnout there, contributing to the underrepresentation of these communities.

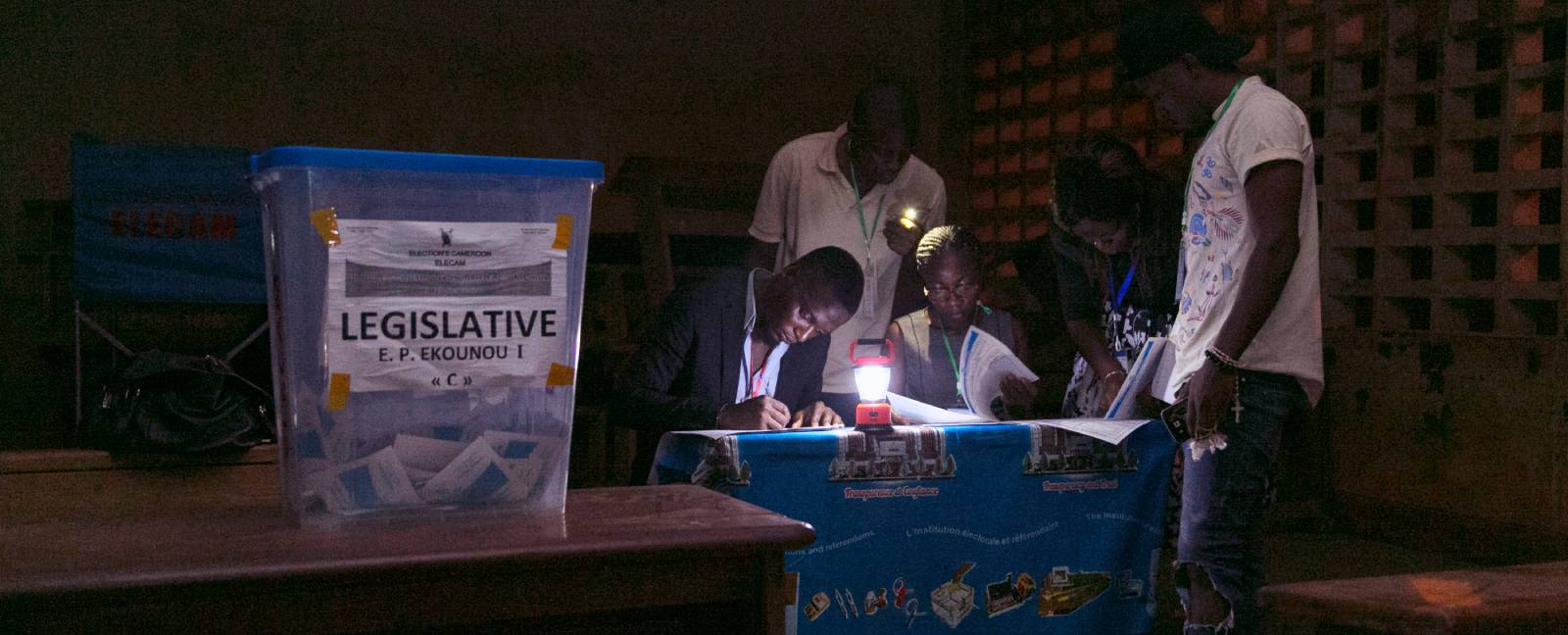

Electoral officials count votes after the general and municipal elections in Yaounde. (Photo: AFP)

Cameroon’s election will also have regional security implications as Cameroon, along with Nigeria and Chad, is confronting a more than decade-long threat from militant Islamist groups (Boko Haram and the Islamic State in West Africa). This threat, focused in Cameroon’s Extreme North Region, has been escalating with the country experiencing a 50-percent increase in the number of annual fatalities (now over 800) linked to these groups in the past year. The degree to which Cameroon’s presidential elections contribute to a legitimating and unifying outcome will directly impact the government’s ability to gain popular support and pursue a holistic stabilization strategy to this threat.

Cameroon is also central to the regional security challenge of protecting the Congo Basin rainforests. Illegal logging in these forests—often linked to transnational organized criminal groups—costs the country billions of dollars in lost revenues, undermines thousands of livelihoods, and threatens the world’s most important terrestrial carbon sink as well as a vital component in Africa’s water transpiration cycles. Cameroonian government leadership will be vital in building both the national and regional security and financial monitoring mechanisms to control this exploitation.

The Cameroon presidential election will likely be subject to external interference.

The Cameroon presidential election will also likely be subject to external interference. Afrique Média, the Russian-sponsored news organization that promotes pro-Russian narratives across Africa, is headquartered in Douala. Russian-linked information networks have supported Biya’s extended tenure, and Cameroon has been a priority target of Russian anti-Western, anti-United Nations, and antidemocracy campaigns.

As Cameroon navigates the inevitable transition from Biya’s four-decade rule, a central theme to watch in the 2025 election is whether reformist forces within and outside the RDPC can gain sufficient traction to build a coalition to address the country’s festering domestic political tensions and regional security threats while realizing the country’s enormous potential.

Tanzania

Tanzania

Presidential and Legislative, October

View this section as separate page

Four years following his death, former President John Magufuli is casting a long shadow over Tanzania’s 2025 elections—and prospects for the country resuming its democratic path. Known as “the bulldozer” for his uncompromising, hardline tactics, Magufuli reshaped Tanzanian politics. From a moderate, dominant-party system widely admired for upholding basic civil liberties, under Magufuli politics grew into a repressive cult of personality that effectively banned opposition parties and disregarded the rule of law in the interest of implementing Magufuli’s agenda and the further domination of the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party. Political violence, previously rare, became normalized—most prominently in the 2017 assassination attempt that left opposition leader Tundu Lissu riddled with 17 bullets.

The CCM and its precursor have been in power since Tanzanian independence in 1961.

President Samia Suluhu Hassan’s ascent to power following Magufuli’s death (believed to be due to COVID) provided an opportunity for the country of 67 million to exhale and tact back toward Tanzania’s historically more moderate political culture.

She introduced reforms restoring civic rights, including lifting bans on media outlets, releasing imprisoned opposition leaders, and creating a more open environment for political dialogue and engagement. In January 2023, she lifted Magufuli’s ban on opposition party rallies.

A government-backed taskforce on political reform recommended in 2022 the establishment of a new, nonpartisan Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and for electoral results to be challengeable in the High Court.

Citizens look for their names on voters lists before casting their vote during a Tanzanian local election. (Photo: AFP)

As part of her 4Rs agenda—reconciliation, resilience, reforms, and rebuilding—Samia met with Tundu Lissu who returned to Tanzania after 5 years in self-imposed exile. Samia, meanwhile, replaced key Magufuli hardliners, including the head of national security, who oversaw the previous president’s brutal crackdown on civil liberties. Reaching across the political aisle, she joined the women’s wing of the opposition Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (Chadema) party to celebrate International Women’s Day in 2023.

These actions won many plaudits at home and abroad, renewing opportunities for expanded international investment in and collaboration with Tanzania.

The opening also provided an opportunity for opposition parties to begin to rebuild their organizational structures and publicly reengage with citizens. Due to the draconian restrictions, bias in electoral processes, and use of violence by Magufuli, most opposition parties had boycotted the 2020 legislative elections—leaving the opposition with diminished official representation. Although there are 19 registered opposition political parties, the 2 with the broadest appeal are Chadema, led by Tundu Lissu, and the Alliance for Change and Transparency (Chama cha Wazalendo, ACT-Wazalendo), led by Zitto Kabwe.

Observers have been dismayed at the return of some of the Magufuli tactics of abduction, intimidation, and killings of CCM critics in the past year.

Given this thawing of domestic politics, many observers have been dismayed at the return of some of the Magufuli tactics of abduction, intimidation, and killings of CCM critics in the past year.

In August 2024, 500 Chadema supporters were arrested ahead of a rally they scheduled on International Youth Day. This included Chadema’s then-Chairman Freeman Mbowe, Vice Chairman Tundu Lissu, and Secretary General John Manyika. The arrests also revived concerns over the politicization of the security sector.

In September, a member of the Chadema party’s secretariat, Ali Mohamed Kibao, was abducted and later discovered dead, showing signs of physical abuse and acid burns on his face—an action Samia quickly condemned. The case appears to be part of a pattern as the Tanganyika Law Society has released a list of 83 individuals who have been abducted or disappeared mysteriously.

Opposition parties protested the disqualification of thousands of their candidates in local elections in November 2024, in which CCM candidates implausibly won 99 percent of the seats by official tallies. By point of comparison, opposition parties garnered 45 percent of the votes in Tanzania’s 2015 legislative elections.

Tanzanian police officers surround a group of young voters following their arrest during the Tanzanian local election in November 2024. (Photo: AFP/Ericky Boniphace)

ACT-Wazalendo filed 51 lawsuits challenging the results of the 2024 local elections, citing irregularities with the drafting of regulations, voter registrations, and nomination of the candidacies.

The media has also come under heightened pressure with three online news platforms—The Citizen, Mwananchi, and Mwanaspoti—suspended for 30 days for publishing cartoons considered critical of Samia.

Meanwhile, proposed electoral reforms, including the reconstitution of the INEC have stalled, leaving the administration of the elections under the control of CCM.

The reversals coincide with internal CCM politics that saw a resurgence of Magufuli hardliners into senior positions within the party. Facing internal challenges and herself an “outsider” among the CCM factions, Samia has evidently felt the need to shore up her base by accommodating the Magufuli camp, rather than expunging these influences.

The struggle over the direction of CCM demonstrates sharp disagreements over the party’s place within Tanzanian society. The CCM and its precursor, the Tanzanian African National Union, have been in power since Tanzanian independence in 1961. In the process, the lines between the party and the state have become blurred. Like other liberation parties in Africa, some CCM members feel entitled to govern indefinitely and, emboldened by Magufuli’s tenure, are willing to resort to whatever tactics needed to maintain their absolute hegemony.

The struggle over the direction of CCM demonstrates sharp disagreements over the party’s place within Tanzanian society.

Others within the party feel CCM can compete via democratic means and can run on a platform of delivering infrastructure projects, strong economic growth, and fiscal responsibility. Given its long history and organizational advantages, this faction believes CCM can be accommodating of democratic reforms, which would enhance the party’s domestic legitimacy and broaden prospects for international investments and partnerships. This includes party elders aligned with the vision of Julius Nyerere, who continue to be very influential. They are the conscience of the CCM and are pushing for a consensus away from the draconian tilt under Magufuli. Samia also offers the CCM a compelling storyline of becoming the first elected female president of Tanzania.

The 2025 elections will be a lens through which this multilayered balancing act plays out. On the surface will be the question of just how much space there will be for the opposition to contest the election—and how much credibility the result will have. Beneath this, however, is the question of how Samia will navigate the various factions within the CCM. The collective outcomes of this juggling will shape the trajectory of Tanzanian democracy and define what the return to “normal” politics in the post-Magufuli era of Tanzania look like.

Côte d’Ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire

Presidential, October

View this section as separate page

Côte d’Ivoire’s elections are shaping up to be among the most transparent and consequential for the continent in 2025. Multiple strong candidates, in addition to President Alassane Ouattara, are likely to contest for the presidency of this country of 32 million people and economic powerhouse in West Africa. With multiple candidates plausibly emerging victorious, the outcome is far from predictable—a positive indicator of competitiveness.

The number of serious candidates is an indication of the growing openness and competitiveness of the Ivorian political system.

Côte d’Ivoire’s relatively propitious position leading into the 2025 elections is noteworthy, given its history of electoral violence. The country experienced nearly 3,000 deaths in the violent aftermath of the 2010 election crisis, when then-President Laurent Gbagbo refused to concede defeat, leading to a descent into armed conflict until the rightful victor, Alassane Ouattara, took power in 2011. This followed a civil war between 2002 and 2007 triggered by transitional military government leader Robert Guéï’s refusal to step down after losing the 2000 elections to Laurent Gbagbo. The conflict fueled ethnic divisions pitting the south of the country versus the north.

The rivalry between Ouattara and Gbagbo has long dominated Ivorian politics, seemingly keeping the country locked in stasis—and fear of returning to the violent polarization of the early 2000s. An effort on both sides to engage in constructive dialogue facilitated the 79-year-old Gbagbo’s return to Côte d’Ivoire in 2021, following an acquittal at the International Criminal Court for his part in crimes against humanity linked to the 2010-2011 political crisis. In the spirit of reconciliation, Ouattara has accorded Gbagbo the full benefits of an ex-president.

While most parties have yet to nominate their candidates, the field is stacked with prominent politicians seen as serious contenders.

Indications are that the 83-year-old Ouattara will contest for his fourth term. During the 2020 election, he had initially decided to step aside for then-Prime Minister Amadou Coulibaly to lead the ruling Rassemblement des houphouëtistes pour la démocratie et la paix (RHDP) party. Following Coulibaly’s sudden death in the run-up to the elections, however, Ouattara stepped back in. A Constitutional Court ruling supported his contention that the 2016 constitutional revision had reset the term-limit clock allowing him to run for two more terms.

Ivorians queue outside of a polling station in order yo cast their ballot in Port Bouet during local elections in Abidjan. (Photo: AFP)

Should Ouattara opt not to run, the RHDP could put forward a younger cohort of candidates, including President of the National Assembly Adama Bictogo or Cissé Bacongo, who is governor of the autonomous district of Abidjan and a former minister of education.

Former Ivorian Prime Minister Pascal Affi N’Guessan is slated to be the presidential candidate for the Front populaire ivoiriene (FPI). N’Guessan had previously contested for the presidency in both 2015 and 2020.

Tidjane Thiam, a former finance minister and former chief executive of Swiss bank Credit Suisse, is a likely contender for the Parti démocratique de Côte d’Ivoire – Rassemblement démocratique africain (PDCI-RDA).

Simone Gbagbo, former First Lady of Côte d’Ivoire and ex-wife of former President Laurent Gbagbo, announced her candidacy for the 2025 presidential election under the banner of her Mouvement des générations capables (MGC) party. Like her ex-husband, Simone Gbagbo was acquitted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity and was subsequently pardoned under an amnesty declaration by Ouattara in 2018.

Laurent Gbagbo, the Ivorian president from 2000 to 2011, has also declared his intention to run again under the Parti des peuples africains – Côte d’Ivoire (PPA-CI). He is barred from contesting, however, due to a jail sentence for looting the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) during the post-election crisis of 2011. While pardoned by President Ouattara in 2022, Gbagbo has not been amnestied, barring him from electoral lists.

Guillaume Soro, a former prime minister under Ouattara, has also announced his plan to contest the 2025 election, though he has been in exile since 2019, stemming from being convicted in absentia in Côte d’Ivoire for “undermining state security” and “handling misappropriated public funds.”

Conditions for the media have also improved in recent years, though reporters may still face intimidation.

The number of serious candidates is an indication of the growing openness and competitiveness of the Ivorian political system. The country’s tumultuous politics of previous cycles and numerous strong personalities, however, portend many storylines and headlines throughout the year.

Recent legislative elections have largely been conducted in a transparent, credible manner. Lower-house elections in March 2021 saw the RHDP lose 28 seats, dropping their total to 139 in the 251-member chamber. In the September 2023 municipal and regional elections, the RHDP won 123 of 201 municipalities and 25 of 31 regions. While Laurent Gbagbo’s PPA-CI has claimed vote rigging, the bigger issue seems to be the PPA-CI’s waning influence, having boycotted all post-2011 elections.

The Independent Electoral Commission, similarly, oversaw a robust and simplified voter registration drive at the end of 2024, which is estimated to have added 4.5 million new voters to the rolls. The drive was extended by a week at the request of opposition parties to allow more citizens to be registered.

Electoral commission officials check the voter’s roll as they count votes at a polling station in Abidjan on October 31, 2020. (Photo: AFP/Issouf Sanogo)

Conditions for the media have also improved in recent years, though reporters may still face intimidation during their investigative reporting. Journalists are also concerned that an electronic communications bill being considered by the legislature could be misused to hinder their work

Working closely with civil society, the Ivorian government’s Haute Autorité pour la bonne gouvernance (HAGB) has also made sustained efforts to counter corruption over the past decade. This has resulted in a steady improvement in Côte d’Ivoire’s ranking on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index—now at 87 out of 180 countries, among the top third of African countries.

To address the growing threat of violent extremist groups spilling across the border from Burkina Faso and Mali, the Ivorian government launched its Programme spécial du Nord in 2022. Combining an increased security presence in its northern border regions with investments in infrastructure and social programs targeting unemployed youth, the program is seen as having contributed to the mitigation of militant Islamist activity in Côte d’Ivoire. Citing the modernization of its armed forces and reflective of the country’s growing self-confidence, President Ouattara publicly announced in early 2025 the negotiated withdrawal of 600 French military forces who had long been stationed in Côte d’Ivoire.

Côte d’Ivoire’s efforts to strengthen its democratic institutions over the past decade have generated tangible benefits for Ivorian citizens. The economy has grown by an average of 5 percent per year during this time, lifting real per capita incomes to over $2,700—an 80-percent increase since 2011.

Increasingly, Russia has tried to seed dissension by sponsoring local influencers who have more credibility with local populations.

Perhaps the biggest wildcard to the Ivorian 2025 elections will be from external influences. Russia has been systematically attempting to undermine democratic processes on the continent as a means of leveraging its influence with unaccountable autocratic regimes. A key element of this has been the aggressive information manipulation campaigns that aim to sow distrust in government and disillusionment in democracy. Côte d’Ivoire is in the crosshairs of this effort being a democratic-leaning Francophone country in West Africa—the locus of Russian influence efforts.

Increasingly, Russia has tried to seed dissension by sponsoring local influencers who have more credibility with local populations. At times, this is through a political party who can benefit from antigovernment sentiments, an angle that some members of Laurent Gbagbo’s PPA-CI party appear to be employing. Of the constellation of Russian-front or Russian-sponsored organizations in Côte d’Ivoire are Solidarité Panafricaniste Côte d’Ivoire, Alternative Citoyenne Ivoirienne, Jeunesse Panafricaine Côte d’Ivoire, Mouvement Citoyen Panafricain Sursaut Africain, and Total Support for Vladimir Putin in Africa.

Having observed the impact of Russia’s information manipulation campaigns elsewhere in West Africa, the Ivorian government and civil society groups have been organizing to counter these intentionally destabilizing narratives through public awareness raising and improving their capacity to expose these Russian-sponsored tactics.

Côte d’Ivoire’s 2025 presidential election benefits from years of still ongoing work to create resilient democratic institutions. How these institutions fare over the course of the year will be a central issue to watch. Integral to a successful process will be the leadership shown by competing candidates while articulating their visions for the future of the country without falling into the trap of polarizing narratives that aim to undercut the many gains the country has realized over the past decade.

Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau

Presidential, November 30

View this section as separate page

Guinea-Bissau electoral environment in 2025 is marked by turmoil and uncertainty—a familiar place for this West African coastal country of 2 million people that has long skidded from one crisis to the next.

Guinea-Bissau was scheduled to go to the polls in December 2024, however, on November 4, President Umaro Sissoco Embaló postponed the elections. The justifications for the delay have been marked by opacity and are being challenged by the opposition as unconstitutional, perpetuating much uncertainty as to when both legislative and presidential elections will be held.

President Úmaro Sissoco Embaló. (Photo: DakarActu TV)

Some observers claim Embaló’s electoral mandate ends on February 27, 2025, and that elections need to be held before then. Embaló contends his term ends in September and that presidential elections can be held in November. It appears that Embaló may be angling to have legislative elections held prior to the presidential polls, in the hopes of regaining a majority that could help him prevail in a presidential contest later in the year.

At the heart of Guinea-Bissau’s governance dysfunction are competing visions of the role of the executive in Guinea-Bissau’s semi-presidential system. Under this arrangement, the president serves as the head of state and the prime minister, selected by parliament, is the head of government—choosing ministers and setting the day-to-day agenda. This system was adopted in the 1993 Constitution to strengthen the separation of powers between the executive, parliament, and judiciary. This was a response to the 19-year rule of President João Bernardo Vieira, who concentrated authority within the executive, facilitating abuses of power and impunity.

Speaker of Parliament Domingos Simões Pereira and his Plataforma Aliança Inclusiva–Terra Ranka (PAI-TR)—a coalition of small parties partnering with the liberation party stalwart, Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC)—put forward constitutional reforms in the June 2023 legislative elections to clarify the powers between the president and prime minister and limit turf rivalries between the two roles. Embaló, a product of the old state-centric presidential system that is close to the military, was instead hoping to secure a parliamentary majority to push through his revanchist vision of presidential power in a new constitution.

PAI-TR emerged victorious with a 54-48 majority in Parliament. The coalition also has the support of another 12 members of parliament (MP) from aligned parties. The result effectively limited Embaló’s expansive view of the presidential authority.

Embaló has responded to this parliamentary setback by creating a shadow cabinet of “presidential advisors,” comprised of former ministers and security officials with close ties to the military and police. Embaló has also attempted to negate legislative authority by dissolving Parliament twice (including in December 2023) alleging coup attempts, and dismissing the parliamentary-selected prime minister, Geraldo Martins. The opposition has been blocked from organizing rallies while parties aligned with Embaló’s have been free to assemble.

The effect Embaló’s actions has been to perpetuate government paralysis.

The effect of these actions has been to perpetuate government paralysis. While Parliament has officially resumed as of September 2024, MPs have been prevented from entering the National Assembly, effectively keeping it shuttered—an outcome Pereira has called a constitutional coup.

Embaló’s postponing the 2024 presidential elections follows a pattern of Embaló jettisoning established institutional processes in the effort to create alternative mechanisms that prolong his time in power and enable his expansive interpretation of executive authority.

The election confusion builds on a long pattern of instability in Guinea-Bissau.

Guinea-Bissau has experienced four coups and more than a dozen attempted coups while enduring 23 years of direct or military government since independence from Portugal in 1973. There have similarly been reports of gunfire and rumors of coup attempts in the country’s capital, Bissau, since Embaló’s November postponement of the 2024 elections.

A former brigadier general in the national army, Embaló ran as the head of the Movimento para Alternância Democrática, Grupo dos 15 (Madem G15)—a breakaway party from PAIGC—during the 2019 presidential elections. He claimed 53.5 percent of the vote versus Pereira’s 46.5 percent in disputed results.

Governmental authority in Guinea-Bissau often equates to control of patronage. This runs the gamut of narcotics trafficking, illegal logging, control of procurement contracts, and diversion of tax revenues. Guinea-Bissau has long been viewed as the prime cocaine trafficking hub in West Africa for Latin American drug cartels, and indications are that narcotics smuggling has increased under Embaló. Guinea-Bissau is ranked 158 out of 180 countries in the world on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

This legacy of patronage has been deeply intertwined with the security services.

This legacy of patronage has been deeply intertwined with the security services. The military and police have historically been used by political leaders to protect their political interests. This politicization has, in turn, incentivized military leaders to use their official positions to pursue their financial interests and, at times, mount coups against their political masters—another driver in Guinea-Bissau’s volatility.

Guinea-Bissau’s persistent instability has impacted the quality of life for its citizens. Roughly two-thirds of the country lives below the poverty line and, with an infant mortality rate of 50 deaths per every 1,000 live births, the country lags behind the continent on many development measures. Improving health and education services were a key part of the PAI-TR’s winning campaign platform in the 2023 legislative elections and will likely feature centrally in the 2025 presidential elections as well.

The 2025 vote, therefore, has significant implications for not only the policy priorities of Guinea-Bissau but also for its model of government and system of checks and balances.

People wait outside a polling station in Bissau early on November 24, 2019, as part of the presidential election in Guinea-Bissau. (Photo: AFP)

Despite its long legacy of political instability, Guinea-Bissau also has a track record of relatively competitive elections and alternations of power. This owes, in part, to the professional composition of the National Electoral Commission (NEC). The NEC Executive Secretariat is comprised of magistrates nominated from the Superior Council of the Judiciary and elected by two-thirds of Parliament for a 4-year term. The dissolutions of Parliament, however, have prevented the filling of vacant posts within the Executive Secretariat, adding further uncertainty to election preparations. A similar predicament prevents the Supreme Court from achieving the quorum needed to validate candidacies.

Guinea-Bissau’s resilient civil society has been a glue that helps the country weather the many bouts of political storms that it faces. This includes violent attacks against journalists who criticize the government. Despite the numerous setbacks, civil society actors continue to push for reforms that would institutionalize more transparency and oversight of public funds and public policymaking so that it serves citizen interests.

The active role of civil society in the 2025 elections will be a critical feature for a credible outcome.

Guinea-Bissau has also benefited over the years from active regional and international engagements. The Economic Community of West African States led by Senegal, the Community of Portuguese Language Countries, the European Union, Portugal, France, and the International Monetary Fund have all sustained engagements to help stabilize Guinea-Bissau. Among other initiatives, this has entailed the deployment of extended peace operations, financial support, and serving as third-party negotiators.

Aside from questions of if and when legislative and presidential elections take place, the bigger electoral story in Guinea-Bissau in 2025 will be about how to build and sustain momentum for a stable system of government and institutional guardrails against the abuse of executive power.

Central African Republic

Central African Republic

Presidential and Legislative, December

View this section as separate page

A blueprint for what can be expected in the Central African Republic’s (CAR) 2025 presidential election can be seen in CAR’s 2023 constitutional referendum. Midway into his second and final constitutionally limited presidential term, President Faustin-Archange Touadéra initiated a constitutional revision to remove the term limit restriction and sidestep this guardrail against the concentration of authority. The effort to evade term limits nearly always occurs within a backdrop of other measures to weaken the rule of law. In the case of Touadéra, this included making the Constitutional Court a government-controlled council, allowing the president to appoint additional justices to the Supreme Court, and voiding the National Assembly’s role in overseeing mining contracts. Presidential terms would also be extended from 5 to 7 years.

The effort to evade term limits nearly always occurs within a backdrop of other measures to weaken the rule of law.

When the head of the Constitutional Court, Danièle Darlan, ruled that the proposed constitutional referendum was illegal, Touadéra replaced her. The campaigning around the subsequent referendum was one-sided, as critics of the power grab—including politicians, media, and civil actors—were barred from holding rallies, intimidated, and detained. Touadéra and his Russian sponsors, meanwhile, dominated the media and social media space in favor of the referendum. This generated the desired outcome, providing Touadéra with a fig leaf, behind which he would run again in 2025.

The referendum, in turn, followed a pattern of strong-arm tactics employed in the 2020 presidential election cycle.

The political space in CAR has only further deteriorated since—with little pretense for fairness. Opposition leaders, such as Member of Parliament Dominique Yandocka, have been imprisoned despite their parliamentary immunity. Civil rights activists, like Crépin Mboli Goumba, have been arrested on charges of defamation and contempt of court. (Mboli Goumba was subsequently detained at the notorious Central Office for the Repression of Banditry for providing documentation of corruption, implicating four judges and the minister of justice). Opposition parties are banned from holding rallies and discredited via organized disinformation campaigns that accuse them of supporting rebel armed groups. Critics are also subject to surveillance, online intimidation, and physical violence by youth militia associated with the ruling Mouvement des cœurs unis (MCU) party. One such group, Les requins (Sharks), conducts armed patrols and beats up suspected opposition supporters. Its founder, Héritier Doneng, was appointed Minister for the Promotion of Youth and Sport in 2024.

Faustin Archange Touadéra (center) greets his supporters at an electoral rally, escorted by the presidential guard and Russian mercenaries. (Photo: AFP/Alexis Huguet)

Intimidation of opposition parties has also been accompanied by a shrinking of the media space. Journalists and media outlets who raise concerns over ongoing insecurity or undue influence of Russia (whose mercenary forces serve as a presidential guard for Touadéra while a Russian serves as national security advisor) are subject to threats, arrests, or closures. As a result, most media outlets now refrain from publishing anything critical of the government or its partnership with Russia. Mimicking Russian information manipulation operations elsewhere in Africa, the Russian-sponsored Galaxie panafricaine engages in aggressive social media campaigns to intimidate government critics in CAR from expressing their opinions. This includes the dissemination of private information of the critics online. Russian forces are also alleged to monitor the movements of critics with drones.

Voters wait as a electoral commission official checks a voter’s roll at the polling station in Bangui. (Photo: AFP/Camille Laffont)

Russia has leveraged its effective capture of the Touadéra government to gain control of CAR’s natural resources, including gold, diamond, and logging concessions. This has led to the effective annexation of territory around these concessions, involving attacks on artisanal miners and evicting local communities from their villages. Incidents include the attack on the Ndassima gold mine in 2021, where Wagner forces killed miners to gain control of the site. Similar attacks occurred in Aïgbado and Yanga in early 2022, with at least 70 people killed. Survivors face continued danger, with reports of disappearances and killings at new mining sites. With Russian plans to establish a permanent military base in the country, CAR offers lessons for other African countries of the risk of lost sovereignty associated with expanded Russian political interference.

CAR’s democratic backsliding—and the reduced avenues for democratic self-correction this entails—has direct implications for citizen well-being. CAR is ranked 149 out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, and an estimated 97.5 percent of its gold production is smuggled out of the country. This level of corruption dramatically limits revenues that could be invested in development initiatives while fueling the criminal trafficking networks that perpetuate CAR’s instability.

The security situation in CAR continues to be volatile, particularly in the northwest and eastern parts of the country, as armed groups compete for control over natural resources and taxes on primary roads. The growing threat posed by these groups has resulted in an 83-percent increase in the number of civilian victims over the past year. Russian and Emirati support for the rebel Rapid Support Forces in neighboring Sudan via CAR adds a regional layer of instability to the decline in accountable governance in CAR.

Despite the risks and the many obstacles to a free and fair electoral process, opposition parties continue to offer alternative paths forward.

Despite the risks and the many obstacles to a free and fair electoral process, opposition parties continue to offer alternative paths forward for CAR. This includes those from the ruling party who have been sidelined and are positioning themselves as an alternative, such as Henri-Marie Dondra, a former prime minister and minister of finance. These reformist efforts merit greater regional and international attention if the growing cycle of impunity is to be broken. Absent that, CAR’s political trajectory will have wider implications for instability, illicit trafficking, and the influence of external actors in the region.

Guinea

Guinea

Presidential and Legislative, September-October

View this section as separate page

The military junta led by then-Colonel Mamadi Doumbouya has announced plans to hold delayed presidential and legislative elections in 2025. This move comes after the military failed to hold promised elections in December 2024, and has showed little commitment to transitioning back to democratic government.

The Guinean junta’s transition roadmap has consistently lacked transparency, timeliness, or adequate budgetary commitments.

The junta seized power from Guinea’s first democratically elected president, Alpha Condé, in September 2021.

Expectations are that Doumbouya will contest for the presidency in the planned elections despite the junta repeatedly saying that all members of the transitional military authority would be barred from serving in a new government.

To pave the way for Doumbouya’s candidacy, the junta is expected to organize a constitutional referendum in May 2025 that would set the terms for the election. Junta members now refer to Doumbouya as President of the Republic, rather than President of the Transition as they had previously.

The junta’s change in tact to pursue elections appears aimed at following the blueprint developed by General Mahamat Déby in Chad, who oversaw a highly orchestrated national dialogue, constitutional referendum that allowed junta leaders to run for elections, and then perfunctory elections in 2024.

The Guinean junta’s 10-point transition roadmap negotiated with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has consistently lacked transparency, timeliness, or adequate budgetary commitments. This has led many civil society leaders to question the junta’s commitment to the transition.

Leader of Guinea’s Junta, Mamadi Doumbouya (C). (Photo: Aboubacarkhoraa)

This view is reinforced by the increasing militarization of the Guinean government. In 2022, Doumbouya replaced the country’s 34 civilian prefects with military officers. In March 2024, Doumbouya dissolved the country’s 342 elected municipal councils, directly appointing their 3,000 replacements. Among other responsibilities, municipal councils are typically charged with organizing elections.

Guinea’s main political parties and civil society organizations, organized under the banner of the Forces vives de Guinée (FVG), have mounted periodic protests (even though these have been banned since 2022) against the junta’s unilateral and opaque control of the transition process. Opposition leaders contend that any election administration or voter registration process should be managed by independent bodies to limit conflicts of interest. Similarly, any constitutional reforms should wait until there is a legitimate, democratically elected government in place.

The junta has responded to such protests with violent crackdowns resulting in dozens of deaths. The military has applied similarly heavy-handed tactics by suspending more than 50 opposition parties, while deeming others “under observation.” Rallies organized in support of Doumbouya, by contrast, are allowed.

Three members of the Guinean opposition—Oumar Sylla (also known as Foniké Menguè), Mamadou Billo Bah, and Mohamed Cissé—were arrested at Menguè’s home in Conakry on July 9, 2024, and taken to a detention facility on Kissa, an island off Conakry, where they were allegedly tortured. While Cissé was eventually released, Menguè and Bah remain unaccounted for. These abductions represent a pattern of escalating harassment, jailings, and trials against critics of the junta, including popular rapper Djanii Alfa. Also in 2024, opposition leader Aliou Bah was picked up by men in uniform and quickly sentenced to 2 years in prison for “offending” Doumbouya.

Resistance to military rule points to Guinea’s resilient civil society and democracy movement.

Members of the Guinean bar have gone on strike to protest the arbitrary arrests and unlawful detentions of Guinean citizens.

Media space is also shrinking, limiting information into and out of Guinea. The junta has restricted internet access, stopped television and radio stations from broadcasting, and pursued a crackdown on independent private media. Sékou Jamal Pendessa, the secretary general of Guinea’s Union of Professional Journalists, was sentenced in February 2024 to 6 months in jail for organizing a protest and threatening public order and the dignity of people through information technology. In July, two media regulators, Djene Diaby and Tawel Camara, from the 13-member High Authority for Communication, were convicted of defaming the head of state after they claimed that the junta had bribed the executives of two (since banned) popular media outlets in exchange for positive coverage.

This resistance to military rule points to Guinea’s resilient civil society and democracy movement. Guinea was one of the last African countries to realize competitive multiparty elections, which did not occur until 2010. This milestone was reached only after the infamous 2009 stadium massacre of more than 150 civilian protesters and the rapes of dozens of women orchestrated by the military government of Moussa Dadis Camara.

Citizens swarm the streets after the outlawed opposition coalition, The National Front for the Defence of the Constitution (FNDC), called for protests against the ruling junta in Conakry on October 20, 2022. (Photo: AFP)

Citizen rejection of military rule in Guinea is based on a long legacy of repressive, unaccountable authority. Guineans suffered greatly under the 25-year dictatorial reign (1958–1984) of Ahmed Sékou Touré, followed by the 24-year regime (1984–2008) of General Lansana Conté. These hardships and hard-earned rights have seared a deep commitment for democracy in the Guinean psyche.

Under the Doumbouya junta, Guinea is suffering from worsening economic strains. Acute food insecurity has skyrocketed to an estimated 11 percent of Guinea’s 14 million people (from 2.6 percent in 2020). Over a million Guineans are now facing food crisis—one of the African countries with the largest increases in populations facing acute food insecurity over the past year. Fuel shortages have become chronic and with annual inflation hovering at 11 percent, access to basic goods is becoming increasingly difficult.

A return to a democratic trajectory would open the country to renewed investment, development, and economic growth.

A return to a democratic trajectory would open the country to renewed investment, development, and economic growth. In its decade of democratic progress, Guinea realized an inflation-adjusted median annual per capita economic growth rate of 2.9 percent. This compares to economic growth of less than 1 percent for the 25-year period before 2010.

A return to civilian democratic rule would also open Guinea’s military to a more robust spectrum of security cooperation funding and training—which could be critical as the militant Islamist insurgency in Mali spreads ever closer to Guinea’s northern border.

Russian interventions to derail the Guinean democratic transition can be expected given Russia’s long involvement in bauxite mining in Guinea, Russia’s outsized influence with neighboring Sahelian military juntas, and the Kremlin’s purposeful efforts to undermine democracy elsewhere in Africa.

Guineans’ pushback against the junta’s gambit to extend its rule is a continuation of the country’s long struggle for democracy in the decades before 2010. That is the fundamental subtext to Guinea’s 2025 electoral calendar. The key issue to watch, then, is the degree to which electoral processes are independently administered versus a military managed exercise that perpetuates military rule under a new name.

More on: Democracy Africa’s Crisis of Coups