Chairman Flake, Ranking Member Markey, and fellow members of the Senate Subcommittee on Africa and Global Health Policy, thank you for the opportunity to speak with you today about the crisis in Burundi.

Chairman Flake, Ranking Member Markey, and fellow members of the Senate Subcommittee on Africa and Global Health Policy, thank you for the opportunity to speak with you today about the crisis in Burundi.

While frequently characterized in ethnic overtones pitting the majority Hutu population against the minority Tutsi, the crisis in Burundi today is not an ethnic conflict. This is a political crisis—an outcome of a political leader and a small cadre of allies aiming to perpetuate their hold on power past constitutionally-mandated term limits. This has triggered a breakdown in Burundi’s popular and heretofore effective process of building a multi-ethnic democratic transition since the conclusion of the country’s 12-year civil war in 2005 in which an estimated 300,000 Burundians lost their lives.

While there are pathways to resolving this crisis, it is important that a resolution be found quickly, before the situation deteriorates to a point of fragmentation and self-perpetuating ethnic conflict such that any solution becomes much more difficult and costly.

The Current Security Situation

The crisis in Burundi was triggered on April 25, when incumbent President Pierre Nkurunziza announced he would seek a third term in office, despite a two-term limit in the country’s constitution. Popular, peaceful protests organized by a multi-ethnic coalition of civil society organizations ensued. So too did an orchestrated campaign of intimidation by a youth militia, the Imbonerakure, which was established, trained, and armed by the ruling CNDD-FDD party for at least a year in advance. The repression escalated following an attempted military coup in May. Opposition strongholds, civil society representatives, and media were especially targeted.

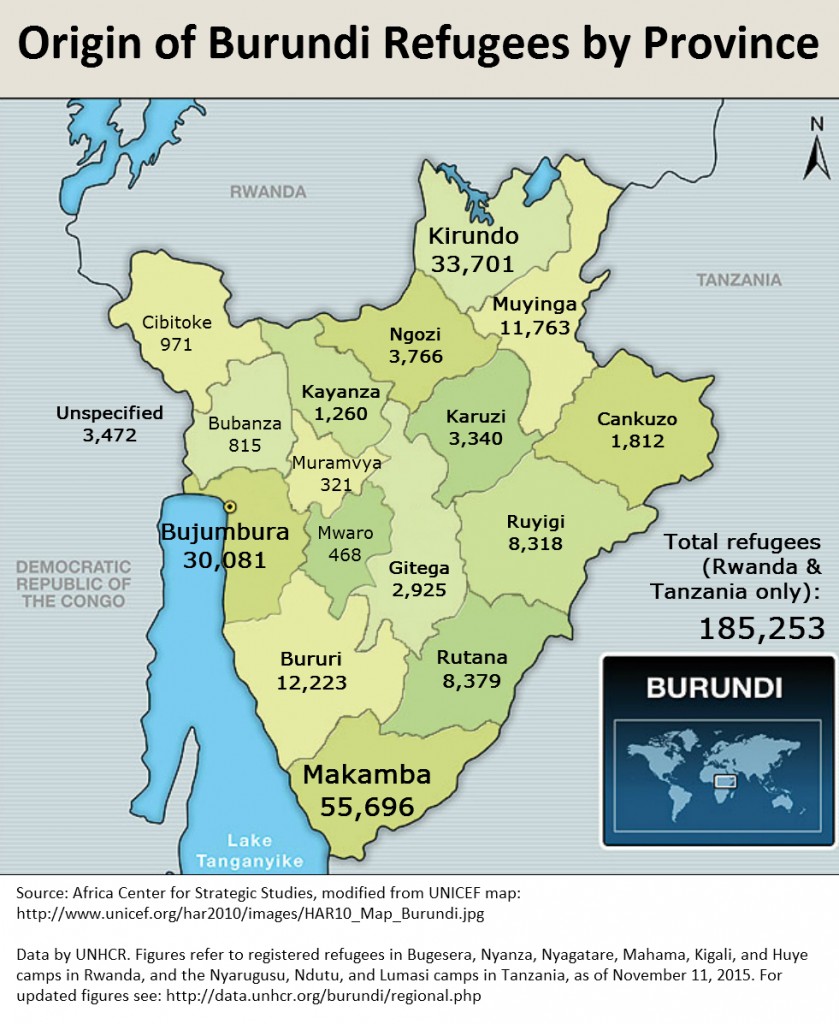

This has led to the deaths of an estimated 500 people and the displacement of 280,000-350,000. Underscoring the political origins of this crisis—and the repercussions for dissent—many senior government officials from the CNDD-FDD opposed to Nkurunziza’s bid for a third term have also fled to exile.

In the face of this intimidation and exodus, peaceful protests have waned and violent reprisals have emerged. In early August, a well-coordinated rocket attack killed the most feared military figure in the country, General Adolphe Nshimirimana. Reflecting an apparent decapitation strategy, several other senior military figures have also been assassinated or targeted. Several dozen police officers have also been attacked. In apparent retaliation, civil society and opposition political leaders or their family members have been killed.

Despite calls from African and international leaders to delay elections until the term limit controversy could be resolved through regional mediation efforts and stability restored, the CNDD-FDD held parliamentary and presidential elections in July. The elections were boycotted by opposition parties and were deemed to lack credibility by the United States, the African Union, the East African Community, the European Union, the United Nations, and the Catholic Church in Burundi.

Keeping track of these fluid developments has been all the more difficult because Burundi’s independent media outlets have been shuttered by government forces since May. Access to independent and corroborated sources of information has become more difficult.

The Fear of Genocide

Raising the stakes further, in an effort to mobilize support among the Hutu majority, the CNDD-FDD has been increasingly employing ethnically polarizing tactics. Purges among senior military and government officials have largely been ethnically based. In November, CNDD-FDD leaders began invoking ethnically incendiary language, recalling the pattern employed in the Rwandan genocide. Emblematic of this was a speech Burundian Senate President Révérien Ndikuriyo gave to supporters in Kirundi on November 3: “… on this issue, you have to pulverize, you have to exterminate—these people are only good for dying. I give you this order, go!” Similar statements were made by other senior government leaders including Pierre Nkurunziza. These remarks triggered a new surge of refugees toward Burundi’s borders.

Swift international condemnation of such language, notably by President Obama, United States Ambassador to the United Nations Samantha Power, and an open letter by International Criminal Court (ICC) Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda that any invocation to ethnic violence would be used as evidence in a future ICC investigation, have led to the tempering of such inflammatory remarks. Nonetheless, the intimidation and targeted killings continue.

In short, the foundation for genocide—the mindset, climate of fear, and polarization—has been laid. Some Burundians have said the level of apprehension is now worse than during the civil war. Then, most of the killing was between armed combatants. Now civilians are also being targeted, causing a greater sense of vulnerability.

Various mediation efforts have been underway since April, led primarily by the African Union and the United Nations. These have been unsuccessful in dissuading Nkurunziza from his determination to hold onto power at all costs, however.

Nkurunziza’s determined resistance to diplomacy and reason, even at risk of precipitating a new civil war and overturning all of the progress Burundi had made over the past decade, has led many Burundians to conclude that the only pressure he will respond to is military force.

Regional Implications

Finding a resolution in Burundi has broader implications than for the country itself. Already the Burundi crisis has placed a burden on its neighbors with 223,000 refugees—mostly in Rwanda and Tanzania. During the 1993–2005 civil war there were 870,000 Burundian refugees, exacting a prolonged economic burden on the region.

Africa’s Great Lakes region has also been host to some of the most prolonged, vicious, and complicated conflicts on the continent over the past two decades—from which the region has only recently been moving past. Further escalation against the population in Burundi could at any time precipitate a military intervention by neighboring Rwanda, where the memories of genocide remain fresh. This, in turn, may spark a military response from other neighbors worried about Rwanda’s influence in the region and recalling previous conflicts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Likewise, there have already been reports of Rwandan Hutu rebel groups operating out of the DRC, notably the Interahamwe, coming into Burundi in support of government-aligned militias.

The outcome of the term limits battle in Burundi also has political implications for the rest of Africa. Since 2000, a dozen African leaders have tried to circumvent term limits that were instituted to limit the monopolization of power and foster a culture of democratic transitions in Africa. Half of those leaders were successful in extending their time in office. The other half, facing concerted domestic and international opposition, were not. In fact, the trend since 2010 has been to block such attempted circumventions. The outcome in Burundi, therefore, will shape the norm on the continent where 19 of 54 African leaders have been in power for more than a decade (and four for more than 30 years). Furthermore, the tactics used in pursuing a third term in Burundi—overriding the constitution, bullying opponents, and then holding rump elections—are a particularly dangerous precedent for Africa if allowed to stand.

Underlying Factors to the Burundi Crisis

Given the devastating social and economic costs to Burundi caused by Pierre Nkurunziza’s decision to pursue a third term in office, as well as strong opposition from within his own party, it is reasonable to reflect on what some of the underlying motivations for this course of action may be.

In addition to the natural desire of many leaders in positions of authority to extend their time in power, Nkurunziza’s efforts to retain control of the presidency likely stem from a Burundian political economy that rewards senior officials financially. Access to political power in Burundi allows for considerable control over public procurement processes, the mining sector, international financial assistance, and reimbursements for peacekeeping deployments. Moreover, presidential power affords control over state-owned monopolies, land and property sales, privatization procedures, as well as import and export restrictions. Burundi scores 159th out of 175 countries on Transparency International’s ranking of most corrupt countries in the world. Furthermore, the government has forcibly intervened when its own anticorruption watchdog has inquired too deeply or publicly.

Another motivation for attempting to stay in power is the desire by some Hutu hardliners in the CNDD-FDD to break out of the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement for Burundi (referred to as the Arusha Accords). Their position is that the Accords are overly restrictive to Hutus, who comprise a strong majority in Burundi. The avoidance of term limits is a violation a key feature of the Accords. If this is accepted, it then offers prospects to renegotiate the entire political framework in Burundi in a manner that will be more conducive to hardline Hutu interests.

A Framework for Stability

Despite the serious challenges involved, this is a political crisis and is amenable to resolution. It is not rooted in deep structural differences within Burundian society. Moreover, a framework for resolution already exists in the Arusha Accords that has guided the country out of its civil conflict since 2000. This includes the precedent of political transitions. Burundi has experienced two peaceful transitions in power under the Accords, first in 2003 and again in 2005. Indeed, one of the greatest tragedies of the current crisis is the obscuring of the exemplary progress within Burundian society that has been made over the past 15 years. By stipulating that political power would not be dominated by either Hutus or Tutsis, the Arusha Accords promoted inter-ethnic political coalition building. This was true for nearly all of the major Burundian political parties including the CNDD-FDD.

Similar patterns took hold within civil society with the result being the fostering of an inter-ethnic national identity—a dramatic departure from the polarization of the past. Revealingly, the protests against Nkurunziza’s bid for a third term were organized by these inter-ethnic civil society alliances involving more than 200 non-governmental organizations who were mutually motivated to upholding Burundi’s fledgling democratic processes.

Perhaps the greatest headway was made within Burundi’s military. Historically Tutsi-dominated, the military embarked on a comprehensive reform program in the mid-2000s that embodied the multi-ethnic principles of the Accords. Trust-building exercises were held at all levels of the military, Hutu and Tutsi recruits were trained together, and values of apolitical military professionalism were inculcated. While incomplete, the process demonstrated dramatic changes in attitudes about ethnicity within the military. Burundian troops also came to play a significant role in peacekeeping missions, especially through their contributions to the African Union’s Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). Its five rotating battalions equate to more than 5,000 troops stationed in Somalia throughout the year. The result has been a relatively strong level of pride and military professionalism.

This professionalism has been on display during the political crisis. Despite extraordinary political pressures, the Burundian military has largely stayed neutral during the crisis. During the protests, soldiers regularly acted as a buffer between protesters and police and government-affiliated militias. Nkurunziza’s inability to depend on the military for domestic political ends has constrained his behavior. That said, the ongoing efforts to politicize the military by arresting and purging Tutsi or moderate Hutu troops have placed great strains on this institution. Defections have ensued with as many as 300 military members having absconded with their weapons as a result.

The enormous value of Burundi’s security sector reforms is underscored by how poorly the police, gendarmerie, and intelligence services have behaved in comparison to the military. These groups are made up mostly of former combatants from Burundi’s civil war who were ineligible for integration into the military. Burundi’s police and intelligence services, therefore, have remained politicized and are collaborating with the CNDD-FDD’s youth league, the Imbonerakure, in cracking down on opposition and spearheading the pro-government violence.

The extent to which the Arusha Accords have become a part of the political fabric in Burundi is evidenced by the serious rift within the CNDD-FDD caused by Nkurunziza’s pursuit of a third term and mobilization of support on an ethnic basis. Some 130 senior CNDD-FDD officials signed a petition in April requesting Nkurunziza to respect the Constitution and the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement. When this was rejected, over 140 CNDD-FDD members, including two senior vice-presidents, left the party (for safety concerns sometimes departing the country clandestinely before voicing their opposition). In July a coalition of opposition parties, senior defectors from the ruling party, and civil society leaders met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia to form the National Council for the Restoration of the Arusha Accords (CNARED). It is leading a broad-based effort to engage in externally facilitated negotiations to establish an Inter-Burundian National Dialogue.

Role for External Actors

Given the high levels of distrust among political parties and limited space for free expression, resolving the conflict in Burundi will require engagement by external actors. Diplomatic efforts in the region should continue to be the focal point for mediation efforts. The United States can support and enhance these initiatives in several ways:

1. Support creation of a multi-party transitional government in Burundi.

As part of its commitment to a political settlement in Burundi, the United States should support the creation of a transitional government in Burundi whose purpose is to oversee a political course back to a constitutional framework and a free, fair, and participatory electoral process. As the institutional mechanisms for a political transition were already in place earlier this year, the objective of this transitional phase would be to reestablish a path for this democratic trajectory. This transitional government of technocrats should be comprised of all leading political parties as well as representatives of civil society. Members of the transitional government would be barred from competing for political office in the succeeding elections. Having fulfilled his constitutionally mandated second term, Pierre Nkurunziza would not be eligible to participate in this transitional government or the subsequent presidential elections.

2. All parties in Burundi must renew their commitment to the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement.

Diplomatic efforts should make clear that the starting point for any political arrangement must be founded on the Arusha Accords. The Accords represent a social contract among Burundi’s ethnically diverse population to end 12 years of civil war and, at times, genocidal massacres that dated back to Burundi’s independence in 1960. The Arusha Accords were intended specifically to prevent future ethnic conflict and its provisions were included in Burundi’s constitution. The highly popular Accords have become no less than a part of the fabric of Burundian national identity and its vision of a multiethnic, democratic society.

Under the Accords no single ethnic group can constitute more than half of the defense and security forces. Similarly, no ethnic group can hold more than two-thirds of local, county, and municipal positions. Across cabinet ministries, the diplomatic service, and the institutions supporting democracy such as the National Electoral Commission, Constitutional Court, National Assembly, and National Commission on Human Rights, no party in power can enjoy more than 60 percent representation.

3. Support deployment of international peacekeeping force.

In order to support a political resolution and foster a stable transition to the Burundi crisis, the United States should logistically and financially support an international peacekeeping force (likely comprising 3,000–5,000 troops) under the auspices of the African Union and United Nations. As at the end of the civil war, such a force would serve as a buffer between rival armed groups to minimize the risk of escalation, enhance civilian protection, as well as to serve as a deterrent to provocations that could trigger mass atrocities. Deploying a peacekeeping force would also serve as a confidence-building measure for all sides, which would help provide assurances to those in exile and among all parties to the conflict that their return and participation in the political dialogue will be supported by institutional safeguards. The African Union has previously called on its members to be prepared to support such a mission. UN Security Council Resolution 2248, furthermore, reminds all of the ICC’s jurisdiction and welcomes the deployment of African Union monitors and military experts.

4. Sanction Spoilers.

The White House’s decision to issue targeted sanctions on four individuals most responsible for the political violence—from both the government and opposition—is an effective way of demonstrating to Burundi’s political elites the personal costs of their actions. The European Union and African Union have also imposed sanctions on a list of individuals and entities.

The United States has also suspended Burundi from eligibility for the preferential trade benefits that come from the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). The EU is debating whether to suspend Burundi’s trade privileges. Belgium and other European bilateral donors have suspended aid to a number of development projects and stopped cooperation with the Burundian police. This is particularly significant since aid accounts for 54 percent of Burundian government expenditures.

The United States should be prepared to expand the scope and breadth of these targeted sanctions as a means of exerting greater pressure on Burundi’s political actors to restore the Arusha Accords and demonstrate a sustained United States commitment to a political resolution. With this aim in mind, the United States should offer its cooperation in evidence-gathering to any International Criminal Court investigation that is undertaken.

5. All non-statutory forces must be disbanded and forensic accounting should identify those responsible for funding them.

Given the central (and unaccountable) role that militias, particularly the Imbonerakure, are playing in intimidating and inflicting violence on the civilian population in Burundi, the United States should support the disbanding of these groups as part of any peacekeeping mandate. The United States should also make available any information, including the forensic accounting of financial flows to these groups, so as to hold responsible those political actors who are sponsoring these militias.

6. The free and independent flow of information should be restored.

A prerequisite to a genuine domestic dialogue and a participatory political process in Burundi is the restoration of independent media and protections for freedom of expression. Independent reporting and access to information are also essential ingredients to maintaining domestic and international accountability. The United States should call for the restoration of all independent print, broadcast, and digital media outlets that have been closed by the Burundian government. Until that time, the United States should expand funding to the Voice of America and exiled Burundian journalists who can tap their networks to report on events inside of Burundi.

The Government of Burundi should be called on to immediately release all journalists who have been arrested. In the absence of any domestic mechanisms to investigate the harassment and violence against journalists, the United States should also sponsor an independent fact-finding mission by the African Union and United Nations regarding the circumstances and parties responsible for journalists who have been killed or imprisoned in the course of trying to do their jobs of informing the general public.

Conclusion

The crisis in Burundi today is political—manufactured by a relatively small number of individuals who do not want to play by the democratic rulebook through which they came to power. In the process, they are attempting to undermine the multi-ethnic political framework that has provided Burundi a pathway away from cycles of genocide to peace and stability. Active international engagement at this point is critical to restoring the Arusha Accords before the cycle of violence and fragmentation accelerates and finding a political solution becomes much more difficult and costly to Burundi, the region, and the international community.

All views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect an institutional position of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies or the Department of Defense.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Burundi: A Critical Juncture,” November 8, 2015.

- Paul Nantulya, “Burundi: Why the Arusha Accords are Central,” August 5, 2015.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Burundi: The Crisis Continues,” May 26, 2015.

- Nicole Ball, “Lessons from Burundi’s Security Sector Reform Process,” Africa Security Brief No. 29, November 30, 2014.

More on: Burundi