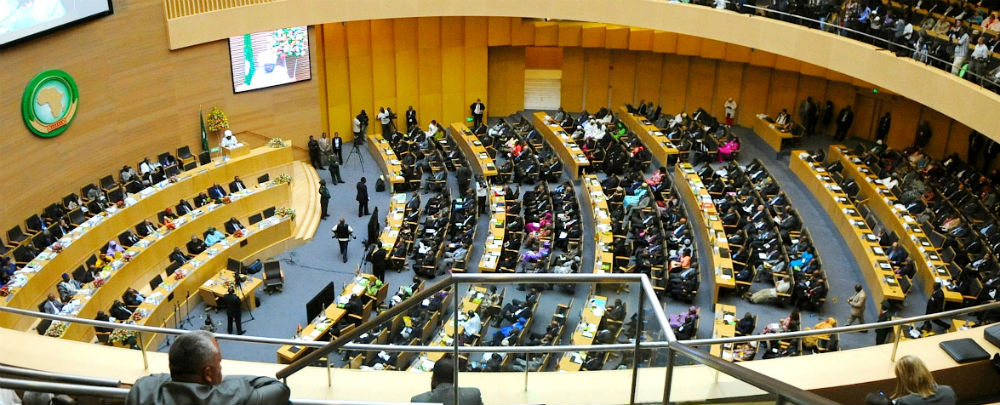

A summit at the African Union in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. (Photo: Department of State)

The African Union’s ability to respond effectively to political crises has been hampered by institutional challenges, dating back to well before it was established to replace the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 2002. Intended to address some of the OAU’s inadequacies, the reforms that laid the foundation of the AU were rooted in the findings of a special OAU panel that investigated the circumstances leading to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, the reasons the international community failed to act sooner, and the institutional gaps that eventually prevented a coherent response from the OAU and the United Nations.

In response to the panel’s findings, the new AU undertook three major reforms.

First, it would prioritize “non-indifference” over the OAU’s principle of “non-intervention.” The new organization would embrace the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine, which asserts that sovereignty is not a privilege but a responsibility and that states cannot invoke it to shield themselves from scrutiny for harming their citizens. Indeed, in such situations, other states are obligated to intervene. This concept was incorporated into the AU’s Constitutive Act under Article 4(h).

Second, it established several new institutions that were meant to be more effective than their predecessors. These included the AU Commission (AUC), which runs day-to-day operations and is mostly staffed by professionals, unlike the OAU’s General Secretariat, which had been dominated by political appointees. The Pan-African Parliament and the Economic, Social, and Cultural Council (ECOSOCC) were also established. Both institutions play a role in the AU’s conflict prevention and management initiatives.

The African Union conference center and office complex in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. (Photo: Maria Dyveke Styve)

Civil society bodies from each of the AU’s five regions and Africa’s diaspora make up the ECOSOCC. The ECOSOCC engages the AU on peace and security issues through its Peace and Security and Political Affairs Committees. It also conducts visits to countries in conflict, prepares reports and analyses on conflict situations, and engages conflicting parties directly. The ECOSOCC’s decision-making body, the General Assembly, at times takes official positions that differ with those taken by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government. The Pan-African Parliament, whose membership reflects the composition of Africa’s 54 legislatures, conducts fact-finding missions, acts as a third-party mediator, and participates in the organization’s peace and security deliberations and decisions. Its specialized Committee on Cooperation, International Relations, and Conflict Resolution works autonomously of other AU organs.

Third, new protocols were set up to enforce ethical standards. Adopted in January 2007, the African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance, for instance, outlines punitive measures against incumbents that refuse to leave power after losing elections, or those that seek to revise constitutions and laws to remain in office at all costs. The Charter entered into force as a legal instrument in 2012 after 15 countries ratified it. It has now been ratified by 32 countries and signed by 46.

Nearly two decades after the AU’s founding, however, many of these reforms have yet to be meaningfully implemented. As a result, the AU is still hobbled by the same institutional weaknesses that stymied the OAU. In a growing number of cases, members have also openly undermined and defied AU resolutions. The AU’s impotence in dealing with situations in DRC, Burundi, and South Sudan, among other crises, shows that the institutional reforms intended to correct the problems of the past have yet to take root.

Political Will

Political will remains the central factor in effectively responding to the crises facing the AU. When longtime Gambian authoritarian leader Yahya Jammeh refused to leave office after his defeat in the 2016 election, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) appointed a negotiating team co-chaired by former Ghanaian President John Dramani Mahama, President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria, Liberia’s President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and President Macky Sall of Senegal, all of whom had been longtime opposition leaders before they assumed office in democratic elections. Their experience predisposed them to champion democratic solutions, not protecting a fellow incumbent. As such, their involvement lent considerable credibility to the decision to approve the use of force that ultimately ended Jammeh’s rule. ECOWAS used a similar model of intervention in Côte d’Ivoire in 2011 that eventually saw Laurent Gbagbo forced from power after refusing to step down following his electoral defeat.

West Africa’s experience has not, by and large, been replicated in other regional economic communities. Mediation efforts led by the Intergovernmental Authority for Development (IGAD), the East Africa Community (EAC), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) have often focused on protecting fellow incumbents. The questionable credibility of some of these leaders with regard to respecting constitutional stipulations and power sharing has meant that the prospects for success in resolving these disputes—many of them triggered by lack of respect for term limits—have been slim.

A meeting of foreign ministers from IGAD member states, with representatives of the European Union. (Photo: EEAS)

A number of leaders are averse to decisions that could set a precedent for the AU to intervene in their own countries. Leaders seeking to avoid censure repeatedly invoke this concern to tamp down the region’s resolve to mount a response.

In the DRC, evidence of systematic rigging in the poll that brought President Felix Tshisekedi to office in January 2019 tarnished the country’s first peaceful transition. The Congolese Conference of Catholic Bishops presented an independent tally corroborated by leaked documents from the Congolese election commission that proved that the government’s provisional results were manipulated.

Election officials shortly before the January 10, 2019, announcement of the DRC election results. (Photo: Radio Okapi)

With evidence of fraud in hand, the AU heads of state and government called for the announcement of final results to be suspended, citing “serious doubts on the conformity of the provisional results.” It also launched mediation talks to move the parties toward an outcome that would respect the integrity of the electoral process and enable Congo’s next administration to start on a strong democratic footing. Less than 48 hours later, however, some members undercut the AU’s footing by distancing themselves from the decision. SADC then walked back its initial call for a recount. Emboldened by this shift, the DRC government promptly disregarded the AU’s position, rebuking it for interference. In short order, other countries announced their support of the election results, even after initially joining the AU in calling the process flawed.

Despite such demonstrations of lack of political will, a number of African governments continue to champion the AU’s reform agenda, though the AU’s two-thirds majority rule relegates them to minority status. The AU, moreover, does not publish the voting records of its members, further obscuring the level of support for the AU reforms.

Structural Challenges

The AU’s troubles are compounded by the overbearing role played by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government vis-à-vis other organs. On paper, bodies like the AUC are supposed to foster more technocratic and evidenced-based decision-making. The Peace and Security Council (PSC) was designed to be institutionally independent to ensure that its functions were not politicized.

Some of these include instituting sanctions and recommending interventions in member states to protect human rights and prevent mass atrocities. The PSC enjoys independence in identifying its agenda items, which cannot be opposed by any member state, including those subject to possible intervention. However, in practice, the authorities of the PSC, AUC, and Assembly of Heads of State, are not clear cut, resulting in confused and overlapping authorities. In general, when there is consensus on an issue, the PSC takes the lead and the Assembly takes the back seat. However, when there is no consensus, the Assembly tends to overturn PSC decisions, undermining both it and other independent institutions. The hierarchy and role of the AUC in decision-making are also unclear. Its effectiveness for the most part is dependent on the initiative of its chairperson and the level of consensus—or lack thereof—on a particular matter before the Assembly.

Burundi President Pierre Nkurunziza

The AU’s engagement in Burundi illustrates how this lack of clarity affects the organization’s coherence and effectiveness in resolving conflicts. When the crisis began unfolding in April 2015, the PSC, with the backing of the AUC, took a proactive stance, meeting monthly and issuing strong resolutions that applied pressure on the Assembly to act. In response to massacres that had been carried out by security forces and militias aligned with Burundian leader Pierre Nkurunziza in December 2015, the PSC adopted a decision to deploy a 5,000-strong civilian protection force. The AUC invoked Article 4(h), which allows intervention without the host government’s consent, and gave Burundi 96 hours to accept the force. However, this resolve evaporated after some members claimed they had not been “properly briefed by their envoys.” Others accused the AUC and the PSC of overstepping their bounds. Countries like Tanzania and South Africa that had initially been supportive of the PSC decision later expressed reservations, further eroding consensus and undermining the decision to intervene. The move to invoke Article 4(h) was attacked by several leaders with questionable democratic credentials, led by Yahya Jammeh, Gambia’s authoritarian leader at the time, who canvassed hard for a policy reversal. Still others claimed they had been misled by Western media reports that exaggerated the seriousness of the crisis.

For his part, the AU Special Representative for the Great Lakes told reporters that the AU “never intended to intervene” and that the idea was simply “unimaginable.” The Burundi government, encouraged by the confusion, warned the AU to stay out of its affairs, adding that it would shoot AU troops if they set foot in Burundi. While Uganda pushed back on the threat, the plan for a deployment was scrapped, and the wide rift between the Assembly and other organs became apparent.

Burundian civil society leaders reacted with anger at the AU’s reversal, with many seeing it as a betrayal of the AU’s very mission.

The Burundi crisis subsequently escalated, resulting in over 2,000 deaths, close to a half million people displaced, and risks of greater regional instability. The economy has shrunk by as much as 7.2 percent. Both the UN Commission of Inquiry on Burundi and the AU Commission on Human and People’s Rights have documented that state actors have committed extensive crimes against humanity since 2015. The Commission on Human and People’s Rights issued a statement in November 2018 condemning the crimes and calling on member states to intensify their efforts to resolve the crisis. Meanwhile, Pierre Nkurunziza continues to hold on to power, not only for a third term—the move that precipitated the crisis in 2015—but with plans to stay on indefinitely.

At the heart of the AU’s paralysis is a tension between the organization’s political arm and its technical arm.

The lack of political will on the part of regional leaders to invoke the collective security responsibility of the AU in the face of political crises demonstrates that the commitment to “non-indifference,” a founding principle of the AU, has waned. So too has the commitment to civilian protection diminished—and with it AU’s credibility and relevance.

At the heart of the AU’s paralysis is a tension between the organization’s political arm (the leaders who gather and vote on decisions at biennial summits) and its technical arm (the AUC). Bodies like the PSC, ECOSOCC, and the Pan-African Parliament have the potential to play a more influential role in the AU. However, they remain effectively consultative bodies and have little influence over executive decisions. In principle, the Pan-African Parliament has powers to craft legislation that is binding on African governments. Yet, only one country, Mali, has ratified its special protocol giving it full legislative powers. Similar problems hamper the African Court on Human and People’s Rights. The ratification of its protocol took 16 years. Even then, only 30 African countries are members, and of these, just 6 accept its power to receive complaints from citizens. Furthermore, the Assembly exempted senior government officials and heads of state from the Court’s jurisdiction, undermining its core mission of combating impunity, promoting accountability, and contributing to the protection of civilians.

A Need to Revisit the Case for Reform

Steered by Rwandan President Paul Kagame, the AU’s latest reform initiative was launched in 2016. Its final report captured the overarching dilemma: “By consistently failing to follow up on the implementation of the decisions we have made, the signal has been sent that they don’t matter. As a result, we have a dysfunctional organization in which member states see little value, global partners find little credibility, and our citizens have no trust.” The report made four broad recommendations:

- Reduce the AU’s unwieldy priorities to four: peace and security, political affairs, economic integration, and global representation

- Reform the organization’s institutions to deliver these priorities

- Undertake measures to achieve financial self-sufficiency

- Manage the AU effectively and efficiently

Several specific proposals were outlined to support these reforms. At the top of the list is the recommendation to restore the independence of the AUC. This includes allowing the Commission chairperson to appoint deputies and commissioners and conducting a thorough review of the PSC, as well as the judicial and legislative bodies, with a view to making them more autonomous.

At the November 2018 AU Summit, leaders were supportive of narrowing the AU’s priorities and streamlining its operations. However, they rejected the recommendations on strengthening the AU Commission.

The failure to achieve consensus on reforms reveals a major disconnect between African heads of state and peace and security experts.

Some SADC members claimed they had not been consulted during the two years of deliberations and circulated a memo expressing disapproval. Even the proposal for countries to charge a 0.2 percent levy on imports to increase the AU’s financial independence met significant resistance. Nonetheless, several countries lobbied for the adoption of these reforms. Moreover, they have vowed to continue their drive to keep these proposals on the AU’s agenda. Some representatives of the Pan-African Parliament and ECOSOCC continue to work with AU members that are supportive of the reforms and are lobbying more member states to adopt them.

The failure to achieve consensus on reforms reveals a major disconnect between African heads of state and peace and security experts. Experience from both the OAU and AU eras suggests that such reforms are urgently needed if the African peace and security architecture is to have a role in practice. Indeed, the rationale for the transition from the OAU to AU will be undermined if reforms do not gain traction.

However, the AU can only be as strong as its members want it to be. The AU’s Kagame Report notes that “reform does not start with the Commission. It starts and ends with the leaders, who must set the right expectations and tempo.” It warns however, that “the cost of inaction will be borne by our citizens, and measured in shortened lives and frustrated ambitions.”

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Term Limits for African Leaders Linked to Stability,” Infographic, February 23, 2018.

- International Refugee Rights Initiative, “From Non-Interference to Non-Indifference: The African Union and the Responsibility to Protect,” Special Report, September 6, 2017.

- Lesley Connolly, “A Year of “Sustaining Peace: What Was Learned from Burundi and Gambia?” IPI Global Observatory, International Peace Institute, April 27, 2017.

- Paul Nantulya, “Lessons from Gambia on Effective Regional Security Cooperation,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 27, 2017.

- Peter Fabricius, “28th AU Summit: ECOWAS Raised the Bar, but Will Others Follow?” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, January 26, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “High Stakes in Gambia: Security Implications,” Spotlight, January 23, 2017.

- Kwesi Aning, “African Agency in R2P: Interventions by the African Union and ECOWAS in Mali, Côte D’Ivoire, and Libya,” International Studies Review No. 17, February 2016.

More on: Conflict Prevention or Mitigation Democratization Regional and International Security Cooperation African Union ECOWAS