The Supreme Court of Zambia. (Photo: Brian Dell)

Progressively authoritarian practices in Tanzania and Zambia are heightening the risk of instability in two countries long seen as among Africa’s most stable. Both were among the first African countries to start a trend of orderly and peaceful transfers of power and avoided the civil wars that have affected many of their neighbors. However, political space is shrinking rapidly in both countries, causing social and political tensions and public unrest. Ordinary citizens now regularly face intimidation for criticizing the government, political opponents are imprisoned and physically assaulted, independent media outlets continue to be closed, and the security actors are increasingly politicized. Citizens in both countries are resisting these infringements on their democratic rights and taking measures to level the playing field ahead of elections in 2020 in Tanzania and 2021 in Zambia.

A Rapid Decline

In June 2016, a year after taking office and following months of actions that chipped away at democratic space, such as blocking live broadcasts of parliamentary debates, Tanzanian President John Magufuli banned public rallies until the 2020 polls, promising to “crack down on troublemakers without mercy.” In 2017, there was a series of unexplained killings and disappearances in Tanzania’s coastal town of Rufiji, one of the regions where rivalry between the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM, or Revolutionary Party) and opposition parties is particularly intense. Azory Gwanda, a journalist who investigated these incidents, disappeared in 2017 and is presumed dead by his family. By January 2018, scores of political leaders had been imprisoned for holding meetings, including eight from the opposition Chama Cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (CHADEMA, or Party for Democracy and Progress). In February 2018, a CHADEMA leader was abducted in the middle of an assembly, only to turn up dead with machete wounds to the head. A few days later, two more CHADEMA officials were found dead, one outside his home and the other on a public beach, also with machete wounds.

Some opposition and civil society leaders have even had their citizenship questioned for criticizing the government.

Some opposition and civil society leaders have even had their citizenship challenged for criticizing the government. Civil society leader, Aidan Eyakuze, had his passport confiscated in August 2018 while the government “investigated” the status of his citizenship. Weeks earlier, his think tank, Twaweza, had published an opinion poll that found that Magufuli’s approval rating had dropped by 25 percent. Other critics have also had their citizenship questioned. They include investigative journalist Erick Kabendera, student leader Omar Nondo, Director of the Tanzania Human Rights Defenders Coalition Onesmo Ole Ngurumwa, Parliamentarian Hussein Bashe, Catholic Bishop Severine Niwe Mugizi, and Protestant Bishop Zachary Kokobe.

In July 2019, the CCM-dominated Parliament passed eight sweeping laws giving the authorities discretionary powers to suspend civil society organizations and private companies, and dictate their internal workings. These controversial laws were adopted with a so-called “certificate of urgency” that allows bills to be rushed without the constitutionally mandated public input and debate.

Similar patterns of democratic decline have emerged in neighboring Zambia since President Edgar Lungu came to power. His ruling Patriotic Front (PF) contested the August 2016 elections amid an internal power struggle that split supporters and put the party on the brink of defeat. In an effort to secure a win, the PF unleashed its youth wing, intelligence, police, and loyalists from the military to intimidate its opposition rivals.

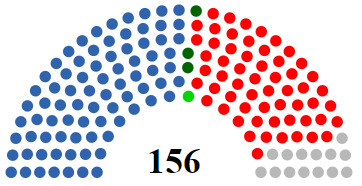

Distribution of seats in Zambia’s legislative body after the 2016 election. (Image: CentreLeftRight)

Government (80):

◼ Patriotic Front (80)

Opposition (62):

◼ UPND (58)

◼ MMD (3)

◼ FDD (1)

Independent (14):

◼ Independents (14)

The electoral process was marred by incidents of violence, voter intimidation, and unbalanced media reporting. Roughly 50 violent incidents occurred between January and June 2016, becoming so intense that campaigns were stopped for 10 days a few weeks before polling. The country’s oldest and most widely circulated daily, the Post, was shut down in June 2016 after reporting on the violence and remains closed.

Lungu was declared the winner of the election by just over 100,000 votes, out of 6.7 million cast, leaving the PF with 89 parliamentary seats and 77 for the opposition and independents. This result was a repeat of the 2015 polls, which Lungu won by only 27,000 votes after droves of PF members defected to the opposition United Party for National Development (UPND). The UPND claims Lungu lacks legitimacy, having failed to win by a commanding lead despite the intimidation and his control of Zambia’s state institutions, including the Electoral Commission. The opposition refuses to recognize him as president and continues to organize civil disobedience campaigns.

Lungu, in turn, seems bent on dismantling any restrictions on his authority and bringing the UPND to heel. In April 2017, UPND leader Hakainde Hichilema and five others were charged with treason for obstructing the president’s motorcade. He was freed in August 2017 but warned by the judge that he could be re-arrested at any time “over the same offense.” In June 2017, 48 opposition deputies were expelled from Parliament for 30 days for boycotting the President’s State of the Nation address. During their suspension, the PF moved quickly to pass a state of emergency, giving Lungu powers to suspend civil rights, prohibit gatherings, and impose curfews. The decree was ostensibly aimed at curbing a wave of arson attacks the President blamed, without evidence, on the opposition. Many saw the move as a way to tighten Lungu’s grip in the face of stiff opposition. By the time the state of emergency was lifted 7 months later, dozens of opposition members and civil society activists were languishing in jail.

In December 2018, the Constitutional Court—whose seven members are presidential loyalists—cleared him to run for a third term in 2021 despite the constitutional two-term limit. Their ruling was based on the determination that Lungu’s first term didn’t count because it lasted just 18 months after the death of the previous president, Michael Sata. There have been dozens of riots in Lusaka and across Zambia since then, resulting in hundreds of arrests and at least three fatalities.

Why Is This Happening Now?

The shift toward authoritarian practices in Tanzania and Zambia unfolded at a time when both ruling parties were facing questions over their legitimacy. Zambia’s Patriotic Front was riddled with internal feuds and faced the real risk of losing power in 2015 and 2016. Though imperfect, Zambia’s elections have always been competitive and unpredictable. In keeping with this pattern, the outcome of the 2016 poll was less than decisive.

Lungu’s authoritarian instincts were apparent when he served concurrently as defense and justice minister in Sata’s government.

The CCM’s dilemma is more of a reputational issue, as its political dominance is more entrenched than its Zambian counterpart. By 2016, CCM’s popularity had taken a hit due to the public’s frustration with rampant corruption, political violence and vote rigging, and the party’s perceived indifference to the country’s growing poverty. The diminished standing of both parties has led ruling party members to support the increasingly authoritarian tactics of their leaders as the cost of victory.

As Magufuli and Lungu secured their hold on power, they subsequently targeted institutional constraints on executive authority—the very features that distinguish democratic systems. Regional and international actors, for their part, have largely watched in silence, unwilling to take steps upholding democratic norms. Lungu’s authoritarian instincts were apparent when he served concurrently as defense and justice minister in Sata’s government. In the power struggle within the PF to succeed Sata, he employed the police to harass challengers to his leadership, which split the party down the middle. Next, he used his power as justice minister to orchestrate the removal of Mutembo Nchito, a highly respected independent public prosecutor, and replace him with a loyalist with questionable legal credentials. Then came the violent crackdown on the opposition, religious groups, and civil society in the run-up to the 2016 elections.

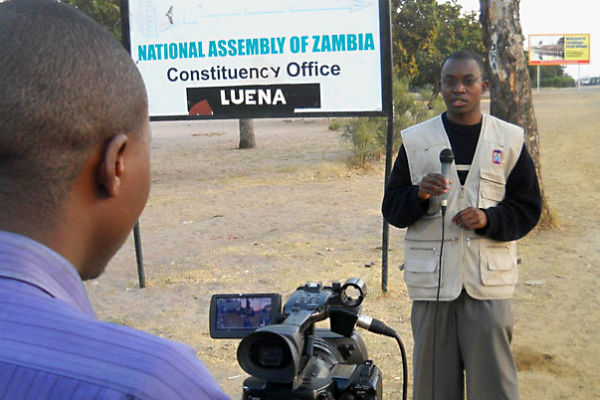

Paul Shalala of Muvi TV, covering the 2011 election in Zambia. (Photo: Mwanaapeluke)

After the polls, the government pressured the Independent Broadcasting Authority to suspend Zambia’s largest independent television station, Muvi TV, for “unprofessional conduct” for hosting opposition commentators. In March 2018, Lungu’s allies launched a defamation campaign against the Law Association of Zambia, one of the country’s oldest and most independent establishments. A PF parliamentarian introduced a bill to abolish it but later withdrew it after public protest. However, it remains on Parliament’s docket, suggesting it could find its way to the floor if lawyers become too critical.

Tanzania’s backsliding has been more gradual than Zambia’s. The CCM’s surprise selection of Magufuli as presidential flagbearer in 2016 was an effort to rebrand the party’s image given its dwindling popularity. Magufuli was considered a political outsider in the CCM and ran a largely independent campaign, distancing himself from the party’s largesse and appealing to disgruntled supporters. His anticorruption message resonated with the party’s base and contributed to the CCM’s victory—albeit with an 18-percent drop in its share of the vote. Still, the party’s inner circle welcomed this, arguing that an establishment candidate would have done far worse.

Magufuli’s elevated position in the party, however, came at a cost. The CCM faithfully complied with his populist agenda and dictates, weakening its role as an internal check. Besides, the party’s powerbrokers were nervous that Magufuli’s anti-graft war would soon turn on them and preferred to remain silent. Magufuli won accolades during his first 6 months: he slashed the size of the cabinet, redirected lavish expenditures for national days to hospitals, and set up a special division of the High Court to handle corruption cases. Several dozen mid- and low-ranking officials were sacked on the spot in his highly publicized impromptu checks on public offices. As predicted by his critics, however, Magufuli used the anticorruption platform to go after those who opposed him. Scores of senior leaders were pushed out or imprisoned, often after a public dressing down by the President.

As predicted by his critics, Magufuli used the anticorruption platform to go after those who opposed him.

Those in the party who have survived his selective purges have sided with Magufuli in his further efforts to erode the country’s democratic norms. As a result, Tanzania’s most important institutions, such as parliament and the judiciary, have been systematically weakened.

The government’s messaging has grown increasingly menacing. In October 2017, several church leaders warned that peace in Tanzania was under threat after opposition leader Tundu Lissu was shot by suspected CCM militants. But rather than provoking restraint, the statement prompted the interior minister to threaten to shut down the churches. In March 2018, the Dodoma police commissioner warned that he would charge the organizers of a planned rally with treason, saying, “They will be beaten like stray dogs.” Magufuli himself cautioned, “Let them demonstrate, and they will see who I am.” The rallies never materialized.

Pushback and Resistance

Democracy activists are determined to push back against Tanzania’s increasing authoritarianism despite the odds. In February 2018, the influential Tanzanian Episcopal Conference, a group of 36 Catholic bishops, issued a statement warning that the growing repression would lead to a further breakdown of trust with citizens. In January 2019, leading civil society organizations formed a coalition to “reclaim Tanzania’s democracy” and safeguard its institutions ahead of the 2020 elections.

In March, they called on the government to protect human rights and open dialogue with the opposition. Magufuli rebuffed them, saying the CCM “will be in power forever, for eternity.” Indeed, reflecting the public’s deep-seated loyalty to “Nyerere’s party,” a 2019 Afrobarometer survey found that 95 percent of Tanzanian respondents said that obeying the CCM, regardless of which party one voted for, was a core political value.

Tanzania’s media has been one of the most diverse in Africa. However, its role as a check on government power has been severely weakened. Regulations adopted in 2018 require online content creators to pay 2 million Tanzanian shillings (about $930) in licensing fees—beyond the reach of most in a country where the per capita GDP is approximately 2.7 million shillings ($1,178). Indeed, the popular corruption investigation platform, Jamii Forums, which has 600,000 subscribers, had to shut down after failing to raise the required funds. It has since come back online, but many other popular media outlets were either forced out of business by these regulations, or by another law, the 2016 Media Service Act, which gives the government the power to ban newspapers and prohibit nonaccredited journalists from publishing. Magufuli gave a stark warning to the media in March 2017 that left little doubt about its intended purpose: “I would like to tell media owners: Be careful, watch it.” In a sign of Tanzania’s weakened judiciary, a court sent two opposition leaders to jail in February 2018 for using “insulting language against President John Magufuli.”

On May 4, 2018, six human rights watchdog groups, media organizations, and bloggers filed a joint case in the High Court of Tanzania in Mtwara Zone and secured an injunction against the Act’s implementation. This was, however, quashed by same court in January 2019—and more media outlets have closed as a result.

Democracy activists are now increasingly resorting to international courts. In June 2018, the East African Court of Justice (EACJ) ordered the government to annul its ban on a local daily, Mseto, though the government has yet to comply. A March 2019 ruling by the EACJ ordered the government to repeal the Media Service Act, but it remains in the books. The African Court of Justice is set to hear 100 cases involving Tanzanians seeking justice for abuses by their government.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) has failed to avert further backsliding in Tanzania and Zambia. Zambia assumed the presidency of SADC’s Organ for Politics, Defense, and Security in 2018 and will remain in the Organ as outgoing chair until 2020, allowing it to continue shaping the body’s agenda. Tanzania was elected chair of SADC’s supreme decision-making body, the Troika, in August 2019. This makes it highly unlikely that SADC will undertake conflict prevention efforts in the two countries.

Lessons from the Backsliding in Tanzania and Zambia

A key lesson from the cases of Tanzania and Zambia is that democracy can never be taken for granted, even within societies where civil liberties seem to have been engrained. The founding presidents of the two countries, Julius Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, seeded a culture of stability and tolerance of criticism, factors that are closely linked in a democratic society. The resilience of civil society in both countries is a testament to this early commitment to civil and political liberties. However, institutions in both countries have proven insufficiently robust to prevent their stifling by power hungry successors. Ruling party reputational incentives, parliamentary process, judicial reviews, and independent media have all been ignored or diminished to a point where they serve little constraint on the unbounded ambitions of their respective executives. Tanzania and Zambia thus demonstrate the limits of judging a country’s democratic health by the personal commitments of individual leaders. Without resilient checks and balances, democracy can be undercut by leaders who refuse to conform to established norms.

In Zambia, in contrast to South Africa when facing similar pressure under President Jacob Zuma, the public protector’s office was unable to provide a platform for independent scrutiny of the executive. Tanzania, meanwhile, highlights the danger of allowing the executive to wield the influence of an anticorruption commission, which provides a powerful political tool to intimidate rivals while appealing to public sympathy. The paradox is that anti-graft mechanisms have ultimately weakened the oversight capabilities for which they were intended.

Without resilient checks and balances, democracy can be undercut by leaders who refuse to conform to established norms.

Lessons from the efforts to subvert democracy in Tanzania and Zambia highlight the need to protect all independent oversight institutions that come under attack. They are strongest when employed collectively. Though each on their own, however, is less likely able to stand up to an executive unwilling to adhere to political norms or the rule of law.

These experiences also underscore the important role of regional organizations when national institutions are under attack. In this case, SADC was itself coopted by the authoritarian tilt of its member states and has been unable to play a conflict prevention role given that two of its most powerful institutions—the Organ for Politics, Defense, and Security and the Troika—were controlled by Tanzania and Zambia.

The African Union and international actors, meanwhile, have been reluctant to enforce stated democratic norms, save for occasional statements of concern and suspension of small amounts of aid. The EACJ has stepped into the vacuum of hollowed-out legal oversight mechanisms to provide an outlet to hear citizen grievances and thus shine some light on the shift away from rule of law. However, the decisions of the EACJ rely on governments in the region to be enforced.

Despite the setbacks observed in Tanzania and Zambia, experience from democratic transitions elsewhere in Africa and globally has shown that even after backsliding, democratic norms and institutions are resilient. Two thirds of countries experiencing a democratic recession revive their democratic progress in a few years. In other words, citizens’ aspirations for freedom tend not to dissipate but deepen, until these rights are restored. Consequently, prospects for democratic renewal in Tanzania and Zambia are hopeful. The question is when—and after how much lost ground, time, lives, and resources.

Additional Resources

- Joseph Siegle, “A Time of Testing for Africa’s Democracies,” presentation at the Emerging Security Sector Leaders seminar, September 28, 2018.

- Telda Mawarire, “Tanzania’s Illiberal Tilt,” Project Syndicate, June 27, 2018.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Term Limits for African Leaders Linked to Stability,” Infographic, February 23, 2018.

- Samuel Gebre and Omar Mohammed, “Rising Authoritarianism Threatens Democracy in East Africa,” Business Day, October 16, 2017.

- Ernest Chanda, “How to Gut a Democracy in Two Years,” Foreign Policy, August 3, 2017.

- Simon Allison, “Can Anyone Stop Zambia’s Slide into Authoritarianism?” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, July 12, 2017.

- Paul Nantulya, “Africa’s Strategic Future: The Consequence of Ethical Leadership,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, October 3, 2015.

- Joseph Siegle, “Why Term Limits Matter for Africa,” Center for Security Studies Blog, July 3, 2015.

- Joseph Siegle, “Overcoming Africa’s Democratic Setbacks,” Brenthurst Analysis, February 2013.

- Aleck Humphrey Cheponda, “Aspects of Nyerere’s Political Philosophy: A Study in the Dynamics of African Political Thought,” African Study Monographs, Volume 1, No. 3, 1984.

More on: Democratization Zambia