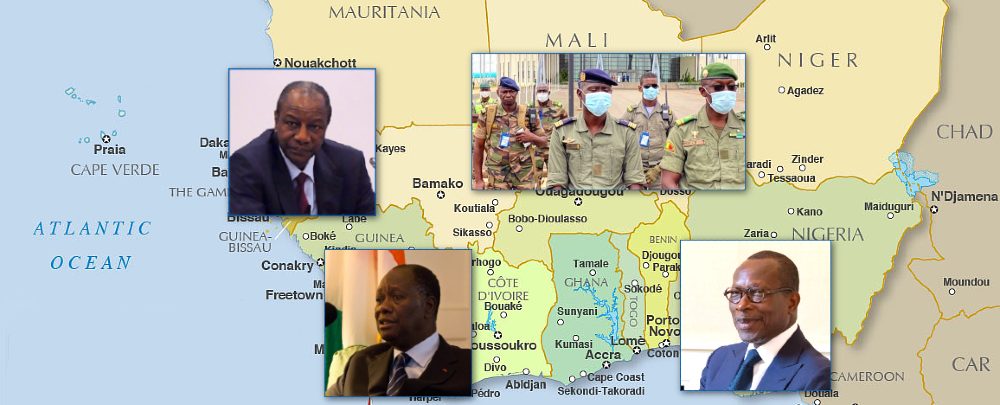

(Map: Nations Online. Photos: Chatham House; VOA/Kassim Traoré; Africa Renewal; Présidence de la République du Bénin)

Over the last two decades, West Africa has led Africa’s transition toward democracy. The recent military uprising in Mali, however, is a wake-up call. Coups can be contagious and democratic gains can be rolled back.

West African leaders and citizens must heed the lessons of recent conflicts in the region. I served as part of the United Nations (UN) peacekeeping missions in Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, and Sierra Leone to help end violent conflicts that were largely a result of exclusive and repressive governance. Elections were a central pillar of our peacebuilding efforts—and a major milestone.

Elections, of course, are only the start of a democratic process. What happens afterward is the tough part. Political space must be protected so that differing views can be heard as part of a participatory discourse. A democracy must also deliver accountable and inclusive governance that improves the lives of its citizens.

“Elections … are only the start of a democratic process. What happens afterward is the tough part.”

Unfortunately, what too often followed elections in West Africa has been disappointment. Democratically elected leaders (and parliaments) have not always lived up to the demands of democracy or abided by its accepted norms. Corruption has flourished. As a consequence, elected officials have failed to build social trust, a vital prerequisite for a functioning democracy.

This does not justify the coup in Mali. It does, however, underscore that other countries in West Africa are vulnerable to democratic disenchantment. The presidents of Mali’s neighboring countries Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea have reversed their earlier commitments to term limits, elevating the risk of conflict in the run-up to presidential elections, and Burkina Faso is struggling with its democratic transition. Meanwhile Benin, which had navigated several peaceful transfers of power, took a step backward during its last, widely criticized election. Democratic rule in Liberia and Sierra Leone, which emerged from violent conflict only a few years ago, remains quite fragile.

Democracy could fall victim to such disappointments. There is a growing sentiment in West Africa that democracy (and especially its leaders) is not delivering on popular hopes for a better future. The economic impact of the COVID-19 crisis has amplified this discontent. There is a risk that people will turn toward more radical or authoritarian alternatives.

Mali coup leaders meet with ECOWAS officials. (Photo: VOA)

So, what might be done to help shore up West Africa’s democracies?

The mandates of both the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States call on these bodies to promote “democratic principles and institutions, popular participation, and good governance.” While the word “democracy” does not appear in the UN’s sustainable development goals, they do call for “effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions.”

Mandate is one thing, action another. While coups are routinely condemned by African institutions and the UN, there is less appetite to intervene preventively when regimes curtail or undermine democratic rights. Nonetheless, this antipathy should not inhibit them from actively engaging national leaders in defense of democratic standards. These organizations must contend with states and their leaders who hide behind sovereignty to forestall such interventions.

Democratic states also should not shy away from engagement even though, out of concern for stability, they are sometimes reluctant to do so. This would be shortsighted because stability is ephemeral when it serves only to protect those in power.

African leaders who have left office because of term limits or electoral defeat offer another avenue for engaging with entrenched leaders. They can speak from experience and by example.

The international community must work with West Africa’s leaders and society to uphold democratic processes. External engagement, however, can only go so far. In the end, democracy cannot be exported, it can only be imported. In other words, the struggle for democracy must be led and sustained by local stakeholders who have credibility and authenticity. They are the foundation of a resilient democracy. Regional and international actors need to support these local actors with diplomatic and material support.

Guineans protesting the possibility of a third term for Alpha Condé. (Photo: FNDC/Labé)

Two groups should be at the forefront because they have the most to lose if democracy fails: youth and women. Young Africans organizing themselves in associations, such as Y’en a Marre in Senegal, can be a powerful voice and force for democratic change. The internet has given youth access to the wider world and the means to mobilize, even in the poorest countries. Women’s organizations, like the Mano River Women’s Peace Network, that have worked to end violent conflict are natural partners in the struggle for democracy and for the rights of women within democracies.

Other elements of society have a role to play as well. Communities of faith can be an important ally for democratic change. In countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, faith communities have exerted a powerful influence when secular powers have refused to accede to popular demands. So too the business community, which is frequently at the mercy of predatory corruption. It has an evident self-interest in promoting accountable governance and the rule of law.

The current crisis in Mali is alarming but not necessarily predictive of the future. Other countries in West Africa like Ghana, Senegal, and more recently, Nigeria have been able to effect political change constitutionally and peacefully. These examples bear emulation. This means that elected leaders must strive to fortify and not erode the foundations of the democratic order. And the international community must remember that democracy is much more than one election, however successful it might be.

Alan Doss is the former President of the Kofi Annan Foundation and the author of A Peacekeeper in Africa: Learning from UN Interventions in Other People’s Wars (2020). He was Special Representative of the Secretary General (SRSG) of the United Nations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2007-2010), SRSG in Liberia (2005-2007), Principal Deputy SRSG in Côte d’Ivoire (2004-2005), and Deputy SRSG in Sierra Leone (2001-2004).

Additional Resources

- Joseph Siegle and Daniel Eizenga, “Mali Coup Offers Lessons in Democracy Building—but Junta Must Go,” The Hill, September 19, 2020.

- Joseph Siegle and Candace Cook, “Circumvention of Term Limits Weakens Governance in Africa,” Infographic, September 14, 2020.

- Alix Boucher, “Defusing the Political Crisis in Guinea,” Spotlight, April 28, 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “ECOWAS Risks Its Hard-Won Reputation,” Spotlight, March 6, 2020.

- Mark Duerksen, “The Testing of Benin’s Democracy,” Spotlight, May 29, 2019.

- Mo Ibrahim and Alan Doss, “Congo’s Election: A Defeat for Democracy, a Disaster for the People,” The Guardian, February 9, 2019.

- Émile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Research Paper No. 6, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2014.

- Mathurin C. Houngnikpo, “Africa’s Militaries: A Missing Link in Democratic Transitions,” Africa Security Brief No. 17, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 2012.

More on: Democratization Benin Côte d'Ivoire Democratization ECOWAS Governance Guinea Mali