Senegalese soldiers in a vehicle near the border with Gambia. (Photo: AFP/Seyllou)

The Senegalese Armed Forces are recognized for their professionalism, their ethical culture, and their apolitical posture. But how did this culture emerge? How is professionalism maintained? How significant are professional military education (PME) institutions in this process, and how do they help to maintain professionalism? What are obstacles to sustaining military professionalism? What lessons can be drawn from Senegal’s experience?

To answer these questions, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies spoke with several Senegalese officers with firsthand experience building this professional culture and the institutions to support it, including:

- General Birame Diop, Military Adviser to the United Nations Department of Peace Operations and former Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of Senegal

- General (ret) Talla Niang, former Deputy Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of Senegal

- A Senegalese colonel with significant experience in PMEs, who asked to remain anonymous to maintain objectivity

How did a culture of military professionalism emerge in Senegal?

According to General Diop, “Discussing military professionalism in Senegal always requires mentioning a happy political coincidence. On the one hand, we had a President, a great intellectual, who was a man of dialogue and peace, Leopold Senghor. At the same time, we had a chief of the armed forces, Jean-Alfred Diallo, also a man of peace, who, because of his training as an engineer, loved to build and believed that the army could play a central role in the country’s development. Therefore, the men who commanded the security sector, and the ones who oversaw these services, benefited very early on from respectful and apolitical relations.”

General Niang adds, “from our elders to now and on to younger generations, we have constantly shared and improved” this conception of the army. Moreover, “the culture of professionalism in the Senegalese Army comes from its very origins. It was created from soldiers who previously served in the French Army. They were relatively strong because they had held all ranks, up to colonel. Many of them had attended Saint Cyr, the French military academy, and had fought in the wars in Indochina and Algeria. These people, upon independence, were given a choice: those who wished to remain in the French Army did, while those who wished to go home to their newly independent country became the initial core of the Senegalese Army.

“These first leaders created an extremely important concept, that of the armée-nation. It’s a concept that holds that the army’s role is to serve the nation, its development, and its security.”

How do you define the army’s role? How do you ensure democratic control of the army?

General Diop explains that “defining the army’s role requires normative documents. The National Security Strategy (NSS) is the mother document, but after that you need concepts of employment, doctrine, general strategies for different ministries to support the NSS, and sectoral strategies. This is the arsenal of normative documents that must be developed. It’s also necessary to have the capacity to review them regularly to update them.”

It’s also necessary to possess “a good mechanism for democratic control of the military by democratically elected authorities. For uniformed personnel to accept political leaders, they must believe that their leaders were elected in a transparent and political fashion.”

How are these values transmitted?

“[The armée-nation] is a concept that holds that the army’s role is to serve the nation, its development, and its security.”

“There has been an effort, particularly among young cadres at our officer schools, to institutionalize the idea that the role of the army is to serve. This issue of transmitting values is essential to how officers view their role,” explains the colonel, adding that “this transmission of values also happens through the example of leadership.”

“There’s another aspect that we don’t discuss as much when we talk about military professionalism—that’s the role of civilians and of civil authorities. We can’t emphasize enough soldiers understanding their role and place in society and of respect for civil authority. But civil authority also has a very important role in realizing military professionalism. Military professionalism must be balanced by civilian professionalism on the other side of the scale.”

What is the role of politicians in this balancing act?

General Mbaye Cissé, Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Senegal, underlined that democratic values must be learned and must not be considered as a given. According to the colonel, “Another important aspect in Africa, is what politicians do. The temptation to bring the army into politics is extremely dangerous. What the military does, how militaries conceive their role, and how a culture of professionalism emerges, is very important. Equally so is the understanding political authorities have of the army’s role. This interaction is crucial.

Senegalese soldiers march during the closing ceremony of a joint military exercise in Saint Louis. (Photo: AFP/Seyllou)

“Senegal’s army and its leaders have always been very firm about the fact that soldiers do not endorse any particular affiliation, be it political, religious, or confessional. Military leaders constantly say, ‘We aren’t involved in these issues.’ The moment in which we live, however, shows that nothing is irreversible. Thus, an ongoing effort is made to institutionalize this view, not just in officer schools, but also for non-commissioned officers (NCO), soldiers, and at all levels.”

In what ways is the composition of the Senegalese Army important to military professionalism?

General Niang explains that “the Senegalese Army benefits from the particularity that its troops mirror the country’s ethnic and regional composition. There is a key or registry that shows this composition. So, if we say that this ethnic group represents 2 percent of the population, we will find those 2 percent in the Army. The Senegalese Army, therefore, is like a microcosm of Senegal itself.”

According to General Diop, “An army cannot be professional if it doesn’t provide adequate work and living conditions. This is the very basis of professionalism. If you take care of your soldiers, they will do their work and take care of you. To be professional, an army requires leaders who don’t think of themselves but who think of their subordinates. The army must work as a team, as a family.”

“Nothing is irreversible. Thus, an ongoing effort is made to institutionalize… at all levels.”

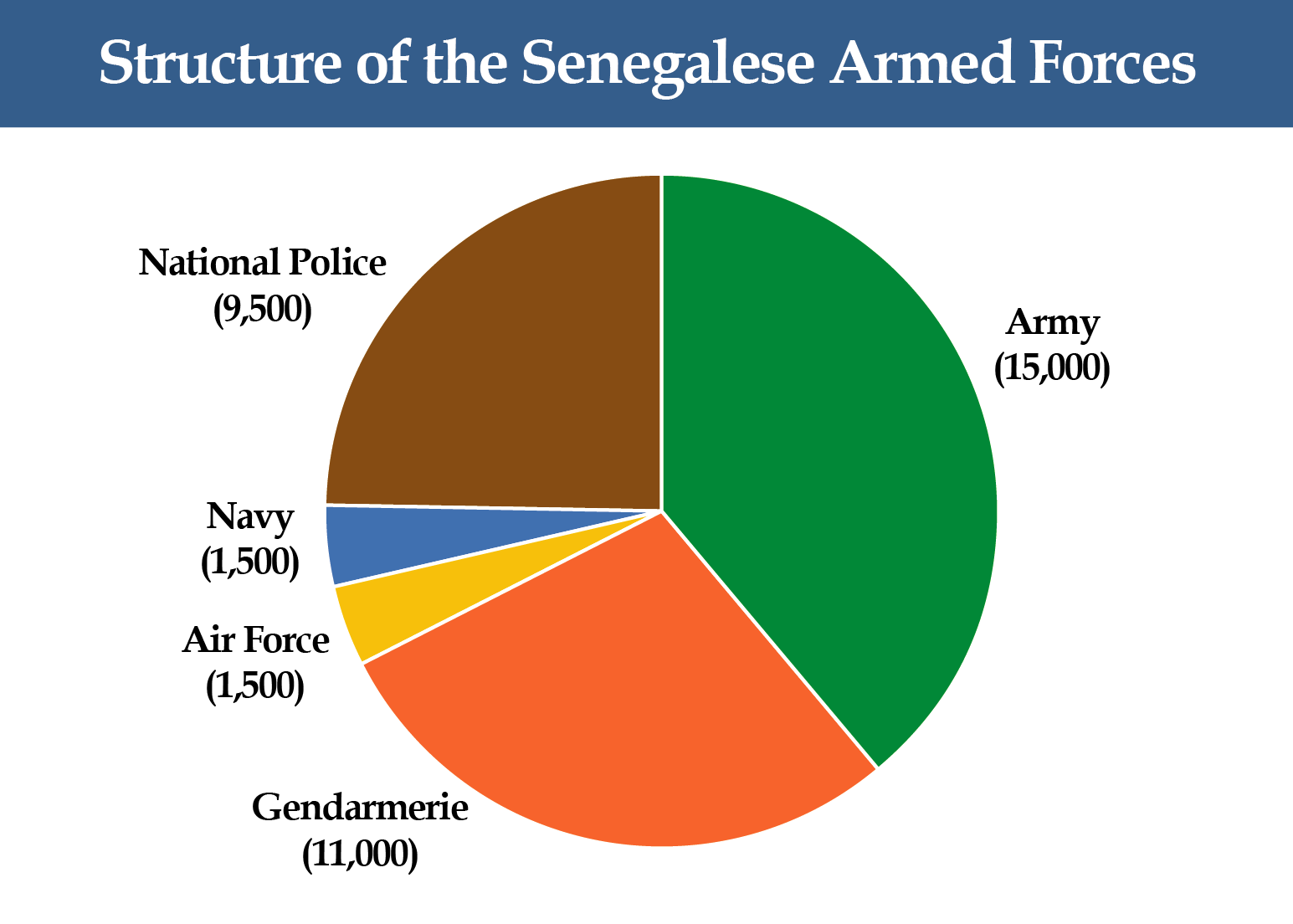

Senegal does not have a presidential guard or special forces units, which is another particularity that contributes to its professionalism. General Niang explains that “In Senegal, the gendarmes statutorily guard the institutions of the republic. Some of these gendarmes are assigned to a presidential group and will serve 2 or 3 years. Then they are sent elsewhere. No one can make a career there. That means that those who guard the President—he doesn’t choose them, he doesn’t know them. The Presidency is an institution. The president does not choose the head of the presidential guard. It’s the chief of the gendarmerie that chooses that officer. A decree is issued to name him—in exactly the same way as for other service chiefs. Members of the presidential guard serve in the same way that they serve in other gendarmerie units. The presidential guard cannot launch a coup in Senegal, they are less equipped, do not have sufficient numbers, and aren’t strong enough.”

What is the role of training in developing military professionalism?

In Senegal, General Niang explains, “All soldiers receive training at a school. We have schools for soldiers, where everyone receives common training, so that all soldiers have the same reflexes, actions, and same rules. After that, soldiers are sent to different battalions, where they receive a specific training to qualify in a certain specialty. This means that when a soldier joins a unit, a squad, they are uniquely qualified for that particular job. They are trained for that role, with the weapon that is required, which is different than what’s used by another soldier. Training is sequenced in a harmonious fashion, no matter the rank, whether one is a soldier, an NCO, an officer, or a senior officer.”

A Senegalese soldier practices shooting with an M4 rifle during training in Dodji. (Photo: DVIDS)

General Niang adds that “There is an annual training cycle at the company level and training at the battalion level so things are coherent. There is interoperability training among tactical groupings of our forces. We also have training cycles with our allies (such as France, the United States, or in the region). Finally, we participate in specific exercises, like Flintlock, where we train staff officers on particular tasks.”

What is the role of promotion mechanisms and of respecting guidance on quotas among the armed forces?

According to General Niang, “another Senegalese particularity, is that it respects quotas on how the army should be organized. In the Senegalese Army, 5 percent are officers, 15 percent are NCOs, and soldiers are 80 percent of the force. As a result, we don’t have too many of any particular rank. Each soldier is in the appropriate place. There are norms and standards to go from one category to another.

“Meritocracy was very rapidly adopted in the Senegalese Army.”

We have promotion commissions, or boards. There is a board at every level—from the company to the battalion, from the battalion to the military zone [in Senegal’s regions], from the military zones to the military branch [Army, Navy, and Air Force], and from these branches to the service directorates to the Office of the Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces, where a ranking is established for all the categories. I had the difficult job of presiding over this highest-level board when I was Deputy Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces. The board included one representative from each service branch [3], representatives from the highest level of each service directorate [7], and the Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces. So, when a promotion to the next grade was being proposed up to rank of lieutenant-colonel, we would rank the candidates and submit the list to the Joint Staff. This was then sent to the Ministry of the Armed Forces for soldiers and NCOs. For officers, the list was sent to the President who names officers by decree. This allows for promotion to be merit-based.

“When you work, you can rise through the ranks in the Senegalese Armed Forces. There is no need for a relative to be in the army, or in parliament, or to be a cabinet minister. I’m the son of a farmer, and I rose to general and number two of the army.”

General Diop adds that “Meritocracy was very rapidly adopted in the Senegalese Army. If you’re promoted on the basis of personal relationships, you may have the rank and the position, but you won’t be accepted or legitimate in the eyes of your peers nor your subordinates. And you won’t be able to give orders to your people so that they execute them without hesitating or complaining. Under a merit-based system, not everyone will always agree with you, but you will have the legitimacy and credibility needed to exercise authority over those you lead.”

What is the Senegalese experience in the creation and maintenance of professional military education institutions? How have they contributed to building military professionalism in Senegal?

The École nationale des officiers d’active (ENOA [the military academy]) was established in 1981. ENOA receives around 100 cadets each year for 2 years of training. Recently, ENOA was reformed and provides the initial training for officers from across the armed forces, including the gendarmerie and the national fire brigade. The Centre des hautes études de défense et de sécurité (CHEDS) was established in 2013, under the authority of the President’s military staff. Each year, around 50 students, civilian and military, receive a masters in defense, peace, and security and, since 2018, a masters in national security. The Institut de défense du Sénégal was established in October 2020. It includes a command and staff college, a war college, and a doctrine development center. Around 25 students attend the command and staff college, while around 10 students were part of its first war college class.

Senegalese soldiers check target impacts during training in Dodji. (Photo: DVIDS)

As General Niang explains, “Senegalese officers are typically educated at a level of either 5 or 6 years after the completion of their high school degree, without exception. This is more than a bachelor’s degree equivalent. But this is only the beginning of training for an officer. Once you’re an officer, you’re going to work hard because you’ll need to attend several schools throughout your career and obtain several diplomas. After 3 years, you’ll attend a school—that we call the captain’s course—in your specialty. After that, you’re given an initial unit, a 150-strong company. That command lasts at least 2 years. After that, you must be assigned to a staff, to learn to write and manage staff matters. And then, you’ll be sent, on the basis of an exam, to the command and staff college.

“In the Senegalese Army, you’re always educated and trained for a particular job before you’re sent to do that job. That way, you know how to do your job. So, after your time in command as a captain, you develop the aptitude for the superior grade diploma (DAGOS), which lasts 2 years and is on-the-job training either in a certain region or on a staff. And if you pass that diploma, you can become eligible to become a major. After that, you can try to take the exam to attend the war college, and then again to attend the National Defense Institute.”

Why did Senegal recently create higher level professional military education schools?

General Diop explains that higher level military education schools were created later because “until then, we didn’t have the critical mass to justify creating such schools. When I became Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, I said that my first job should be to create a defense and security institute. I believed that Senegal had reached a level of maturity that justified having our own school.”

The colonel interviewed elaborated, “Do we need a war college? Yes, but it’s an extremely complex issue. Many neighboring countries have recently created one, including Mali and Côte d’Ivoire. Clearly, as part of the growth process in the Senegalese Army, the need to have more officers who have graduated from the war college, or from other schools, is expanding. As we were not keeping up with these demands, it led to the creation of these higher level schools, as well as of several specialty schools.”

What is the role of NCO schools and of training for soldiers?

General Niang explains that “For NCOs, we have three schools—Army, Air Force, and Navy. In each of these schools, the NCO chooses a service to obtain a certification. There is a diploma to become a sergeant, a master-sergeant, a warrant officer, and a chief warrant officer. You have to get these diplomas to rise in the ranks. Then there are the schools for the lower ranks, where we train soldiers and from which we choose those that could one day become corporal and obtain a diploma to become master corporal. So, everything is clear. When you’re ambitious, you can start as a soldier and end as a chief warrant officer, or even a lieutenant. Everything is based on schooling and behavior.” Moreover, as detailed by the colonel, “There has been, these last few years, a lot of effort, in these courses and modules that are given in our recruitment centers, our NCO schools, and our officer schools, to insist on values of professionalism and democratic civilian control of the military.”

A Senegalese brigadier general speaks to soldiers from the First Parachute Battalion after a live fire exercise in Thiès, Senegal. (Photo: DVIDS)

What have been or could become obstacles to building these norms, values, and institutions?

The lack of sufficient access to training. As the colonel explained, one of the difficulties linked to dependence on foreign training is that fact that, “You have needs to meet, but you are dependent on seats being offered to meet them. So, if you need to train officers, be it in high level officer schools or in very specific specialty schools, and you depend on offers from France or other foreign countries, these offers can vary widely. You never know how many spots will be offered each year. We found ourselves in situations where we had officers we wanted to train in a certain specialty, but it wasn’t possible because that training was dependent on being given slots abroad.”

The risks that politicians attempt to politicize the armed forces. According to the colonel, “Our presidents, in general, have not sought to interfere with matters relating to the army’s internal management, be it promotions, advancement, or the nomination of certain officers as service chiefs. But this must not be taken for granted.” Until 2006, soldiers did not have the right to vote in Senegal. “And when we began voting, it was on a separate day because soldiers had to work to provide security for the elections, so we voted a week in advance.” As the late General Lamine Cissé, a former force commander for UN missions and former Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces once observed, “The hierarchy was apprehensive about giving the military the right to vote because of the risk that it could become politicized.”

In March 2023, the Senegalese General Staff of the Armed Forces in fact published a communiqué calling on “political actors from all sides and on civil society to keep the army out of political debates, in the interest of the nation. The army intends to maintain its apolitical posture and to focus on its statutory missions.”

Takeaways from Senegal’s Experience in Building and Maintaining Military Professionalism

“Another very important part of developing a culture of military professionalism is the dialogue that must exist between civilians and the military to achieve it.”

A unified force, with no presidential guard or a divided force that works at different speeds. “In many countries in our neighborhood, politicians haven’t helped,” explains the colonel. “When you create an army where different services or branches work at different speeds”—for instance a presidential guard or a special forces unit—”with the goal of maintaining your hold on power, politicians do not help by doing this.”

The importance of reinforcing civilian capacity for control and accountability in civilian administrations and in the army. “Another very important part of developing a culture of military professionalism is the dialogue that must exist between civilians and the military to achieve it. Civilians must be knowledgeable about military matters. This is a weakness in many countries in Africa. Expertise in defense and security is primarily found within the army and the security sector, and somewhat among civilians in the ministries of foreign affairs and defense. Civilians often don’t know the army and security issues well. And if you don’t have civilian expertise in defense and security issues, you have to depend exclusively on uniformed personnel.

“The capacity for civilian control, be it in the executive or in the legislature, is essential however, because without it, the security sector is relatively autonomous. This civilian oversight is fundamental. Defense and security parliamentary committees do not always grasp the breadth of these issues, other than perhaps voting on the budget. At the parliamentary level, such training would reinforce this capacity. Interactions between parliament and the armed forces can be limited. The Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces has, for instance, never testified before the parliamentary committee,” says the colonel. Only in 2021 did the National Assembly, for the first time, debate in plenary before voting on the budget for the Ministry of the Armed Forces.

Develop and widely disseminate the National Security Strategy, along with sectoral strategies, review them regularly, and use more inclusive processes in their development. According to the colonel, “A weakness in our countries is that we do not have this culture of developing these strategies that are meant to define the role of the armed forces and delineate its limits. Senegal has recently done so. What’s lacking, however, is that it hasn’t been widely disseminated among officers and civilian personnel in the ministries. In Senegal, this work was multidisciplinary, but these documents are not yet reviewed at regular intervals and are not mandated by law. Finally, the national assembly needs to better understand its responsibilities when it comes to defense and security. There is likewise not always enough discussion, be it within civilian ministries, civil society, the media, etc., so that a sufficient segment of society is aware of the national security strategy.”

Additional Resources

- Dan Kuwali, “Oversight and Accountability to Improve Security Sector Governance in Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 42, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, September 2023.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “The Role of Parliamentary Committees in Building Accountable, Sustainable, and Professional Security Sectors,” Spotlight, April 3, 2023.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Deepening a Culture of Military Professionalism in Africa,” Spotlight, December 20, 2022.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Professional Military Education Institutions in Africa,” Infographic, February 25, 2022.

- Colonel Khar Diouf, “L’enseignement militaire : Un recentrage sur des structures militaires autonomes : Le nouveau pôle dédié à la formation des personnels des Forces armées sénégalaises (FAS),” Armée-Nation 59, avril 2021.

- Jahara Matisek, “An Effective Senegalese Military Enclave: The Armée-Nation ‘Rolls On’,” African Security, 12:1 (2019), 62-86.

- Kwesi Aning and Joseph Siegle, “Assessing Attitudes of the Next Generation of African Security Sector Professionals,” Africa Center Research Paper 7, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 2019.

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Africa Center Research Paper 6, Africa Center for Strategic Studies July 2014.