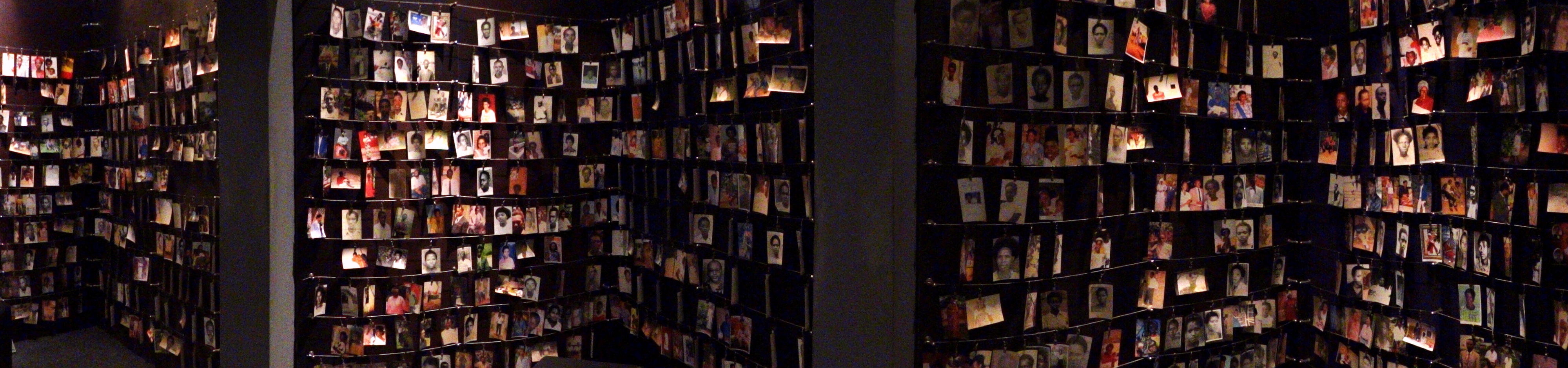

Photos of Genocide Victims, Genocide Memorial Centre, Kigali. (Photo: Adam Jones.)

Each April, the international community commemorates the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, reflecting on the vow to “never again” allow such an atrocity to occur. However, mass violence has been on the rise in Africa. The African Union and United Nations have both warned about the onset of genocide in Burundi and South Sudan. Mass atrocities were also documented in the Central African Republic in 2015 and have recently flared in the Democratic Republic of Congo. What explains this resurgence in violence? And what are some key lessons that might be applied in addressing them—and in preventing future ones? Genocide scholar Samantha Lakin reflects on these questions and current efforts to prevent genocide on the continent.

Question: The terms genocide, ethnic cleansing, and mass atrocities are often used interchangeably. How are they different?

SAMANTHA LAKIN: Genocide, ethnic cleansing, war crimes, and crimes against humanity are all classified within the larger frame of mass atrocities.

Genocide is the targeting with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, members of an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group. Some analysts include other categories such as political affiliation or gender, and other methods of genocide, including the destruction of cultural sites. These categories are gaining currency in customary international practice. In 2016, Ahmad al Faqi al Mahdi, an Al Qaeda operative, pleaded guilty at the International Criminal Court (ICC) to destroying shrines and damaging a mosque in the ancient city of Timbuktu in Mali, marking the Court’s first prosecution of the destruction of cultural heritage as a war crime.

Srebrenica massacre memorial. (Photo: Michael Büker.)

The term ethnic cleansing was originally used to refer specifically to the crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia, where atrocities were committed against an ethnic group, but where intent to destroy was not easily established. While not a legal term, ethnic cleansing refers to a variety of actions including killings, physical harm, torture, rape, or forced removal, aimed at permanently moving a particular racial, ethnic, national, or political group from a given territory.

Being clear about the classification of these crimes can help provide context for the causes, patterns, and possible solutions to the violence. They also help us distinguish and understand each case of mass atrocity within its own cultural and political context, as well as historical patterns. Every society has its own unique culture and language of violence, as well as moral codes and coping mechanisms.

Mass atrocities take on many different forms. These range from systematic killings that are carried out over time, the pattern of which are not immediately apparent, to killings on a massive scale over a short period of time, as we witnessed in Rwanda. No two situations are the same. If we fall into the trap of using one crisis as the “default” template, then we risk missing early warnings of the onset of mass atrocities, making prevention impossible.

Q: What are the reasons for the resurgence of genocidal violence that we now see in places such as Burundi and South Sudan, and what are the impediments to action?

SL: The first reason has to do with the dynamics of how political power is exercised in many fragile contexts in Africa. The risk of violence that could lead to mass atrocities is always present when the state and its security institutions are organized to serve narrow individual interests. This is further aggravated when constituencies are framed in ethnic, regional, or racial terms. Part of the problem is that government and the military are often seen as avenues for wealth and status, a motivation that makes the competition for power particularly heated and violent. Ruling elites in such situations have shown a disturbing willingness to do whatever it takes to retain power, including exploiting ethnic divides.

The risk of violence that could lead to mass atrocities is always present when the state and its security institutions are organized to serve narrow individual interests.

Second, accountability mechanisms are either weak, as in the case of Burundi, or non-existent, as in the cases of South Sudan and the Central African Republic. Peace negotiations focused on power-sharing among rival forces that have committed atrocities have built-in incentives for protagonists to strike immunity deals (usually in the form of blanket amnesties). Guaranteed impunity for their actions often then fosters a culture of violence in the post-conflict period.

The Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement for Burundi had strong accountability mechanisms. However, the protagonists were keen to secure immunity from prosecution and so their implementation focused on power-sharing. This has given the government license to mobilize against the opposition with little fear of sanction. In the process, the government has been able to tighten its grip on power. In Sudan and South Sudan, it was the lack of accountability that sowed the seeds for the recurrence of violence and mass atrocities.

Interest- and values-based negotiations tend to look deeper into the underlying causes of conflict to create architectures that will ensure that they do not recur.

Third, external guarantors of peace agreements often pull back from the post-conflict context and have been reluctant to hold signatories accountable when they violate terms of the agreement. Agreements in South Sudan and Burundi, for example, provided strong regional and international monitoring mechanisms. However, these were ultimately not consistently enforced. In Burundi, regional and international actors opted not to intervene during the run-up to the 2010 elections after there were clear signs that the situation there was going to deteriorate. The pattern of atrocities leading up to the 2015 elections was eerily similar, and again, there were no effective deterrents to such behavior.

South Sudan showed warning signs at least as far back as 2009, yet external interventions were weak or ineffective. Regional and international actors placed far greater emphasis on implementing the referendum for independence than on addressing the serious rifts that were emerging among South Sudan’s political actors. One of the key early warning signs was the militarization of the ruling party, as well as growing cleavages in the military as individual commanders jostled for influence, whipping up ethnic animosities in the process to strengthen their positions. In 2013, a long-simmering power struggle within the SPLM finally exploded into open violence and spread to the military where it quickly took on ethnic dimensions. This institutional breakdown contributed to the mass killings that continue to this day.

Internally displaced persons at Kiwanja camp in, North Kivu, DRC. (Photo: Julien Harneis.)

In the DRC, the patterns of violence are tied to legacies and practices of extortion, marginalization, and power politics. The breakdown of central authority and a pervasive climate of impunity have contributed to a situation where killings and massacres routinely take place as a tactic of control, and to spread fear. The seemingly random nature of these crimes often makes it difficult to establish intent, but emerging practice, norms, and jurisprudence are paying closer attention to what is being called “politicide”—targeted violence that is aimed at political opponents. Often, politicide can take on an ethnic character, especially if it is allowed to fester, as political elites have a tendency to resort to ethnic incitement when faced with mounting pressure.

The cases of the Central African Republic, South Sudan, Burundi, and the DRC share one key element: the manner in which power has been exercised has contributed to deadly violence. Political elites have sought to control political power to the exclusion of sections of the population and have fashioned security forces to protect regime survival as opposed to citizens. As such, the resurgence of genocidal violence in Africa over the past decade reflects in part a backward trend in democratization. Unless core issues of governance and accountability are seriously addressed, mass atrocities will remain a threat.

Q: What are some lessons that have been learned about genocide in the past two decades?

Anti-Balaka militia members. (Photo: Bagassi Koura, VOA French.)

SL: The first major lesson is the need to act promptly on early warning signs. In the Central African Republic, tensions between Muslim and Christian communities periodically flared up over several decades, which should have served as a warning to the international community that they would eventually explode into a severe crisis. That crisis came in 2013, following months of looting and killing by the mostly Muslim Seleka rebels, who had overthrown the government, clashing with the mostly Christian anti-Balaka militias taking up arms in response.

Rwanda similarly underwent several episodes of extreme and targeted violence at different periods since independence. These should have been sufficient predictors of a possible impending genocide. Today, advances in technology have increased the sophistication of early warning systems, but it has not necessarily translated into preventative action. This gap in the larger policy architecture needs to be addressed.

When accountability is set aside in the interest of addressing more immediate manifestations of violence, it softens the ground for conflicts to recur.

Studying the cases where the potential for genocide existed but did not unfold can also help inform prevention efforts.

Mali had many of the same precursors and inter-ethnic animosities as Rwanda, but the conflicts there did not degenerate into genocide. In Rwanda, the nation’s myth after independence was founded on animosity, built on a narrative that the Tutsi minority had mistreated the Hutus during colonization. In contrast, Malians shared a common history that all ethnic groups embraced, in addition to strong cultural value systems of humility, tolerance, and solidarity. These communal ties were instrumental in preventing genocide, as Scott Straus found in his seminal work on genocide prevention.

In Côte d’Ivoire, independence leaders, key among them Félix Houphouët-Boigny, created and vigorously propagated a national founding ideal that downplayed internal divisions and emphasized the country’s multi-ethnic identity. For decades the country was stable and prosperous. But that was undermined when Houphouët-Boigny’s successor, Henri Konan Bédié, sought to capitalize on voter anxiety about a failing economy by speaking out against Ivorians whose parents were not born in the country before independence.

Ivorian refugees in Liberia.

He popularized “Ivoirité” or “Ivoirianness,” an idea that was taken to the extreme by two successive presidents. Despite heavy incitement to violence, the instability in Côte d’Ivoire did not morph into communal killing, and Laurent Gbagbo, who served as president from 2000–11, was taken into custody by the ICC for crimes against humanity. Ivoirian political and military elites frequently cite the resilience of the country’s founding ideal among a cross-section of Ivoirians as being key to preventing genocide.

Similar signs of community resilience appear to be at play today in Burundi, where the conflict is being largely driven by government-sponsored militias and their allies in the security forces, and not by communities. Furthermore, cross-ethnic solidarity is strong among government opponents, as well as the survivors of violence.

Strategic and discreet engagement with reform-minded actors in government and the security services is key for preventative action.

Finally, strategic and discreet engagement with reform-minded actors in government and the security services is key for preventative action. Much of the evidentiary material that has been collected by UN monitors in situations of mass atrocity come from sources within the government apparatus, including many defectors. Support to these elements is crucial because it reinforces the notion that the system is not monolithic and that the designs of those driving the violence will be uncovered.

Samantha Lakin is a Ph.D. candidate at the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University. Currently, Lakin serves as the Team Lead for Gender and Corruption in Congo with CDA Collaborative Learning. Lakin also serves on the Board of Trustees for the Survivors Fund (SURF), and the Advisory Board of the Genocide Survivors Support Network.

Additional Resources

- Godfrey Musila, “Preventing Genocide: Africa’s Evolving Normative and Institutional Framework,” Spotlight, April 7, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Dismantling the Arusha Accords as the Burundi Crisis Rages On,” Spotlight, March 13, 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Conflict and Famine in South Sudan,” Spotlight, March 20, 2017.

- Joseph Siegle, “Constitutional Design: Vital but Insufficient for Conflict Management in Africa,” Ethnopolitics, Spring 2016.

- Scott Straus, “Making and Unmaking Nations: War, Leadership, and Genocide in Modern Africa,” Cornell University Press, April 2015.

- Alison Des Forges, “Ten Lessons to Prevent Genocide,” Human Rights Watch, March 29, 2004.

- United States Institute of Peace, “Mobilizing the Will to Intervene: Leadership and Action to Prevent Mass Atrocities,” public roundtable, September 21, 2009.

More on: Conflict Prevention or Mitigation Identity Conflict Ethnic Conflict Genocide Governance