(From a photo by Henri Bergius)

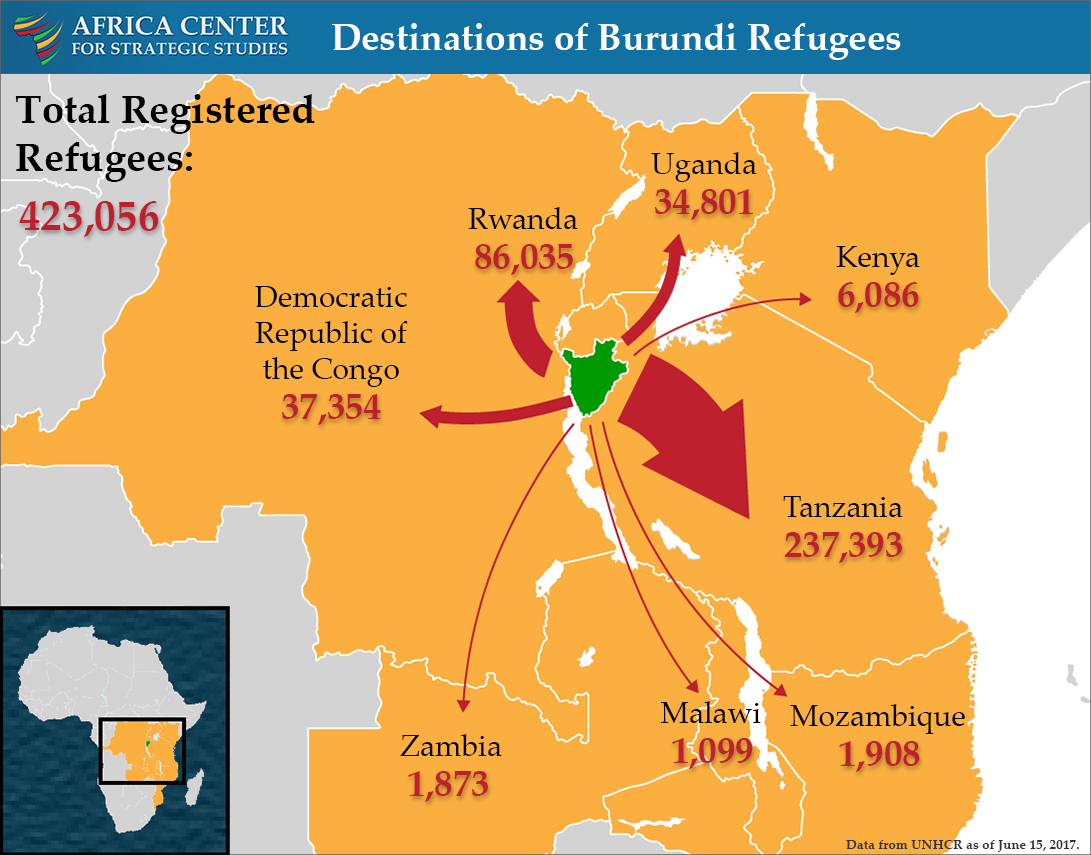

In June 2017, the UN Commission of Inquiry on Burundi reported that atrocities were being committed on a massive scale. This includes extrajudicial executions, torture, sexual and gender-based violence, enforced disappearances, and mass graves. Many of the violations were accompanied by ethnic-based hate speech delivered by state and ruling party officials. Over 400,000 Burundians have taken refuge in neighboring countries, including 240,000 in Tanzania’s Nyarugusu camp, now the third largest in the world. The number of Burundian refugees is expected to exceed a half million by the end of this year, which would make Burundi the third largest source of refugees in sub-Saharan Africa.

Burundi’s troubles are costing the EAC hundreds of millions of dollars annually

The crisis is taking a toll on the economic outlook of the East African Community (EAC). Several infrastructure projects are in danger of derailing, including the extension of a regional pipeline for oil products, estimated at $53 million. Resource mobilization for the Kenya-Uganda-Rwanda portion, valued at $193 million, continues, but the Burundi section, which would extend to the capital, Bujumbura, has stalled. Similarly, plans to extend rail links from the Mombasa and Dar es Salaam ports to Bujumbura have frozen, as has the 220Kv electricity transmission line between Rwanda and Burundi, which is part of a $390-million project to connect the power grids of Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. These and other major economic and infrastructure projects have been halted due to insecurity, as well as funding shortfalls resulting from the sanctions imposed on Burundi by key external economic partners. In March 2015, a few months before the Burundi crisis erupted, donors pledged $2 billion in new funding for EAC infrastructure priority projects. The European Union portion of that funding is part of a 600 million euro ($705 million) allocation to the African Union (AU) Regional Economic Communities that would support the EAC’s Regional Development Strategy. In March 2016 the EU adopted sanctions and other restrictive measures on Burundi that effectively freezes many of these commitments. Undoubtedly, much private investment in the region has also been lost as investors steer clear of the regional instability.

The upshot is that Burundi’s troubles are costing the EAC hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Despite these concrete costs, the reaction of Burundi’s neighbors has been remarkably subdued. Conflict resolution efforts led by the EAC have floundered. In July 2015, the regional body launched a negotiation process between Burundi’s ruling party and the opposition, with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni as mediator and former Tanzanian President Benjamin Mkapa as facilitator. Both leaders were pivotal in the Arusha peace process of 1996 to 2005 that ended Burundi’s first civil war, but the current process has struggled to take off. Six EAC summits have failed to make any significant impact. And the only action regarding Burundi taken at the May 2017 summit was a call for the European Union (EU) to lift sanctions on Burundi before member states sign the EAC/EU Partnership Agreement. While the EAC adopted Mkapa’s progress report on negotiations, it has failed to tackle the issues he forwarded for urgent action, such as pressuring Burundi to lift arrest warrants against its opponents and create conditions for the return of political exiles and refugees, the release of political prisoners, and the inclusion of armed groups in the peace process.

Despite the May summit being postponed twice to accommodate schedules, only Museveni and Tanzanian President John Magufuli attended out of six invited leaders. Nkurunziza has not attended a summit since 2015. In December 2016, the EAC said it would reach a comprehensive agreement by June 2017. Yet that date came and went.

This paralysis is seen to have reinforced Nkurunziza’s intransigence and emboldened those in his circle pursuing military action. It has also undermined the EAC’s credibility and called into question the functionality of the African Peace and Security Architecture and its stated commitment to advance “African solutions to African problems.”

Lack of Strategic Coherence among EAC Members

The limited political will demonstrated by Burundi’s neighbors has hobbled the EAC’s ability to effectively address the crisis. On May 30, 2015, the EAC attorneys general submitted a legal opinion to EAC heads of state that found that Nkurunziza’s pursuit of a third term to be unconstitutional and a violation of the Arusha Accords. But former Tanzanian President Jakaya Kikwete prevailed on his fellow leaders to drop the issue on the grounds that they had no authority to comment on domestic matters. Ultimately, the EAC leaders called for “a return to the constitutional order” and an end to the violence. In June 2015, Museveni offered Nkurunziza a 10-point exit plan that would have seen him stay on through a two-year transition, leading to elections in which he would not stand as a candidate. He promptly rebuffed the proposal. Since then, Uganda appears to have delegated the effort to Mkapa.

Some blame the lack of cohesion on the May 13, 2015 coup attempt that occurred as an EAC summit on Burundi got underway in Dar es Salaam. Member states were already divided over how to respond to Nkurunziza’s controversial bid for a third term. The attempt to oust Nkurunziza through unconstitutional means merely widened these differences. Rwanda boycotted the first emergency summit after the coup attempt. Rwanda and Kenya boycotted the second, and Uganda joined them in boycotting the third. The fourth—which Mkapa called for specifically to “look into obstacles dragging the dialogue”—was aborted entirely. (In the midst of its own conflict, EAC member South Sudan is not involved in the Burundi discussions.)

A 2009 meeting of EAC heads of state. Left to right: Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, Mwai Kibaki of Kenya, Paul Kagame of Rwanda, Jakaya Kikwete of Tanzania, Pierre Nkurunziza of Burundi. (Photo: nukta77)

Rwanda’s boycotts convey pessimism and frustration. It has been at odds with the Nkurunziza regime since the crisis erupted and President Paul Kagame has openly expressed concern about the violence in Burundi given Rwanda’s similar ethnic makeup and history of genocide. At the same time, tensions between Tanzania and Rwanda have added to the EAC’s woes. After Jakaya Kikwete’s call in June 2013 for Rwanda to enter into a dialogue with the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda—a remnant of the forces accused of committing genocide in 1994—the hostility between the two countries escalated to threats of military action. Kikwete’s successor, John Magufuli, has worked to reduce tensions, but suspicions remain due in part to Tanzania’s perceived closeness to Burundi’s ruling party.

Key Decisions Not Implemented

To be sure, the EAC did take some initial bold steps to address the crisis but it failed to follow through and implement them. In September 2014, the EAC Summit created a joint EAC–Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) Panel of the Wise to defuse tensions. After spending three months in Burundi consulting the government, civil society, opposition and ruling party leaders, and the military, the Panel drew up a list of 10 issues for discussion in what would have been an African-led national dialogue in Burundi. Bujumbura rejected the proposal, and the EAC, instead of using the report to rally a common approach, shelved it.

Next, the EAC Council of Foreign Ministers warned EAC leaders ahead of their May 31, 2015, emergency summit that allowing Nkurunziza to stay on could cause a crisis of legitimacy, erode the Arusha Accords, create dissension in the army, and escalate the violence. The summit pushed for a 45-day postponement of elections and other measures to reduce tensions—none of which were implemented. Burundi postponed its July 21 presidential polls by one week, which were boycotted by the opposition and marred by violence.

The EAC found itself in the awkward position of accepting an electoral outcome that its organs found questionable on legal and political grounds

Given the inauspicious environment, the AU refused to send in election observers, while the EAC observer mission concluded that they were “neither free nor fair.” This should have triggered articles 146 and 147 of the EAC Treaty, clauses that provide remedies to persistent violations of treaty principles and member decisions that affect the Community. Instead, the EAC found itself in the awkward position of accepting an electoral outcome that its organs found questionable on legal and political grounds. The EAC summit held on September 8, 2016, approved a fresh road map consisting of a series of engagements between December 2016 and May 2017 that would culminate in a comprehensive agreement in June 2017. However, the parties did not meet face to face and the government boycotted talks in February 2017 that should have addressed outstanding issues ahead of the June deadline.

The African Union Unable to Step In

With the EAC seemingly unable to move the peace process forward, the role of the African Union took on greater prominence. The AU broke some new ground on December 17, 2015, by deciding to deploy a 5,000-strong protection force in response to massacres in Bujumbura on December 12 of that year and the AU fact-finding mission’s report, which came out shortly thereafter. The resolve was short-lived, however. Tanzania and other countries initially backed the force before reversing themselves. The decision was adopted by consensus in the AU’s Peace and Security Council, but some countries complained that they had “not been properly briefed” by their representatives on the Council. Many delegations also felt that the AU Commission had overstepped its bounds in a decision that in their view should have been left to the Assembly of Heads of State and Government to make. Still others argued that they had been “misled by civil society and Western media coverage on the crisis” and that the situation in Burundi was “not as severe.” Such reservations played a central role in the decision by countries like Tanzania and South Africa to stall the implementation of the AU Peace and Security Council’s decision to deploy the force.

Contradictory messages dealt a major blow to the AU’s credibility and leverage

Future Steps for the EAC

In February 2017, Benjamin Mkapa told EAC leaders that there was an “imperative need” for their “personal engagement” in getting the Burundi authorities to “commit to serious dialogue without preconditions.” At their summit in June, when a final deal was supposed to have been concluded, he said, “There is an impasse because the Government of Burundi is reluctant to talk to its opponents … and picking friendly stakeholders to talk to while ignoring others.” He warned that the government “has to realize that reconciliation is between two opposing camps and not between friends.”

The EAC, which has only existed in its current form since 2000, was not designed to play a conflict resolution role

Since 2013, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda have initiated major projects among themselves to fast track the region’s drive toward establishing the East African Federation, while Tanzania and Burundi pulled in the opposite direction. Member states have disagreed on tariffs, assessed contributions, and management issues, while the EAC’s budget constraints have left it unable to foot the bills of the Burundi mediation. Kenya is the only member that has fully paid its assessed contributions.

However, the potential for unity and progress is still there. Some EAC members were part of the Great Lakes Regional Initiative on Burundi, a body created in 1999 to reinforce the Arusha peace process mediated first by former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere and then former South African President Nelson Mandela. The Regional Initiative spoke with one voice and had a shared vision. This enabled it to mobilize Burundi’s neighbors to impose a land blockade and trade embargo to compel the parties to negotiate. As a pivotal member of the initiative, South Africa deployed a civilian protection force that was later joined by two other members, Ethiopia and Mozambique, and the African Mission to Burundi, the AU’s first peace enforcement mission.

Although leaders of the caliber and moral suasion of Nyerere and Mandela are in short supply today, even Mandela would not have succeeded without the full, unified backing of the members of the Regional Initiative. This lesson is especially pertinent today in light of Mkapa’s repeated appeals for leaders to play a more active role in backing the peace process.

“There is an impasse because the Government of Burundi is reluctant to talk to its opponents … and picking friendly stakeholders to talk to while ignoring others.”

Conflict resolution is tough business even in the best of conditions. The Arusha peace process consumed four years of negotiations, a three-year transition, and two years of ceasefire talks. The South Sudan peace process took 11 years, starting with the 1994 Declaration of Principles and ending with the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement. Those processes were driven by robust political will by regional actors, coupled with a common approach and decisive action. And the burden was shared with extra-regional actors who played complementary roles. The EAC will need to consider these lessons and the role it hopes to play as a regional body if it intends to rescue current mediation efforts in Burundi. It may then be in a position to reverse the economic and political costs its members are bearing for the ongoing political crisis in Burundi.

Additional Resources

- Paul Nantulya, “Burundi: Why the Arusha Accords are Central,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 5, 2015.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Dismantling the Arusha Accords as the Burundi Crisis Rages On,” Spotlight, March 13, 2015.

- Ty McCormick, “The Burundi Intervention That Wasn’t,” Foreign Policy, February 2, 2016.

- Adelin Hatungimana, Jenny Theron, and Anton Popic, “Peace Agreements in Burundi: Assessing their Impact,” Conflict Trends, Issue 3, 2007.

- Kristina A. Bentley and Roger Southall, An African Peace Process Mandela, South Africa and Burundi, Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa, 2005.

More on: Conflict Prevention or Mitigation Regional and International Security Cooperation African Union Burundi Leadership