Chadian soldiers in Bosso, Niger. (Photo: VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

On March 23, Boko Haram militants staged a complex attack on Chadian troops stationed at a base in Bohoma. The attack lasted for 7 hours and ultimately left 98 Chadian soldiers dead and dozens more wounded. The battle of Bohoma (alternatively spelled Bohouma, Bouma, and Boma) highlights worrying improvements to Boko Haram’s combat and intelligence capacities, given that the Chadian Army has been widely considered the superior regional force.

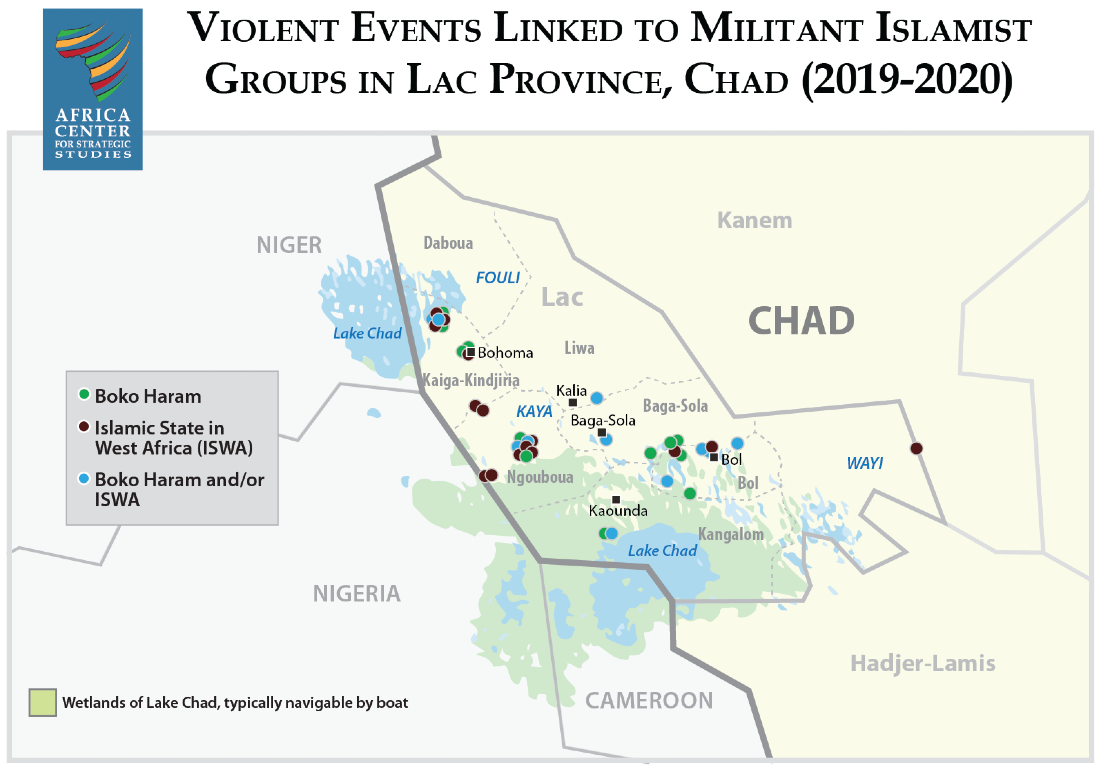

The attack follows years of insurgency waged by Boko Haram and its offshoot, the Islamic State in West Africa (ISWA), in the Lake Chad Basin. These have largely been concentrated in northern Nigeria but also in northern Cameroon, southeastern Niger, and western Chad. Within Chad, militant Islamist group activity has been concentrated in Lac Province, which encompasses all Chadian territory around and across the lake. The number of confrontations between insurgents and Chadian soldiers tripled from 7 in 2018 to 21 in 2019. Moreover, in an apparent change of tactics since the beginning of 2019, civilian communities in Chad have been targeted 15 times resulting in dozens of casualties and abductions.

The violence has displaced nearly 170,000 people in Lac Province, roughly one-third of the Chadian population in that area. It also has endangered livelihoods by hindering agricultural production and blocking cross-border trade, both contributing to the UN’s estimate that 5.3 million people in Chad will require humanitarian assistance in 2020.

After the March 23 attack, the Chadian military launched an offensive led by President Idriss Déby to clear the insurgents from Chadian territory. Boko Haram’s ability to accomplish such a devastating attack, along with the preceding increase in militant Islamist group activity in Chad’s Lac Province, however, raises the prospect that Boko Haram and ISWA have gained momentum and now pose a greater threat to Chad and stability in the wider region.

Boko Haram’s Activities in Chad

The scale and threat of Boko Haram and ISWA’s activities in Chad have fluctuated over the years. The January 2015 massacre of roughly 2,000 civilians at Baga Kawa, Nigeria (sometimes referred to only as Baga), an important trading hub and port on Lake Chad, prompted the mobilization of more than 1,000 Chadian soldiers into Nigeria to push Boko Haram out of its strongholds in Borno State, Nigeria. The operation was a success, but the fallout was swift. Boko Haram quickly planned and executed multiple suicide attacks in N’Djamena during 2015, and its dispersed militants set up camps across the many islands on the lake, including those in Lac Province.

This initial period from 2015 to 2016 saw an influx in violence for communities in Chad along the Cameroonian and Nigerian borders. However, by the end of 2016, the security situation on the Chadian side of the lake began to improve due to the military’s sustained presence and a containment strategy that discouraged encroachments on Chadian communities. At this time, most Boko Haram activity took place elsewhere in the broader Lake Chad region.

“Al Barnawi has renounced attacks on Muslim civilians, while Shekau freely targets non–Boko Haram Muslim civilians.”

By late 2016, Boko Haram had split into two factions: one led by Abubakar Shekau and the other led by Abu Musab al Barnawi, becoming ISWA. The two factions separated over differences in tactics and ideology. For instance, ISWA is not known to conduct female suicide bombings, while Shekau’s Boko Haram is. Also, al Barnawi has renounced attacks on Muslim civilians, while Shekau freely targets non–Boko Haram Muslim civilians, declaring them apostates. Over time, the influence of each grew over different geographic spaces. Shekau’s faction established a stronghold in Sambisa Forest and the Mandara Mountains in northeastern Nigeria and parts of northern Cameroon. Meanwhile, al Barnawi’s faction maintained a presence along the Nigerian shores of Lake Chad and the Niger-Nigerian border.

One contingent of militants operating around Lake Chad led by Ibrahim Bakura, also known as Bakura Doron, concentrated its activities around the northern basin of Lake Chad. This contingent actively raided communities in the borderlands of the lake, especially in Niger during the 2016-2017 timeframe. By 2018, the Bakura-led faction of fighters had established itself under the leadership of Shekau and began to target military outposts in Nigeria and Cameroon. In Chad, their activities primarily took place in Kaiga-Kindjiria Sous-Préfecture, an area bordering Niger and Nigeria.

Boko Haram flag across from Bosso border post in Niger. (Photo: EC/ECHO/Anouk Delafortrie)

Despite these raids, insecurity from Boko Haram and ISWA factions operating in Chad remained relatively contained for much of 2017 and throughout 2018. Over the course of 2019, however, the threat of insecurity posed by Boko Haram and ISWA in Chad steadily grew in Lac Province (see map). The strategic objectives of the increased attacks remain unclear, though some have speculated that it may be linked to leadership changes within ISWA, the steady growth of the Bakura-led faction of fighters that remains loyal to Shekau, or competition between the two groups.

The Attack on Bohoma

The rise in the number of attacks and fatalities in Chad in 2019 suggests that the March 23 attack on the military outpost at Bohoma fits a trend of Boko Haram and ISWA gaining ground and capabilities in Chad. During the attack at Bohoma, hundreds of militants stormed the military base on four sides from at least five boats fitted with outboard motors. The surprise attack began just before dawn and continued until the Chadian soldiers were overrun around noon. Boko Haram militants then sacked the base, looting significant materiel and destroying the equipment they left behind, including roughly two dozen military vehicles. The attack is the most significant launched by Boko Haram outside of Nigeria in recent years.

Beyond Boko Haram’s surprise tactics and sizable number of forces, the battle demonstrated that Boko Haram forces in the region have improved their intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities. The Boko Haram militants were able to successfully ambush reinforcements while they were en route to support those under attack at Bohoma. Militants may have also known that the troops at Bohoma had recently been relieved by soldiers with less familiarity of the area and experience combatting the insurgents. Furthermore, the fact that hundreds of Boko Haram fighters could be mobilized without the Chadians detecting their movements suggests a failing on the part of Chadian ISR capabilities.

“The March 23 attack on the military outpost at Bohoma fits a trend of Boko Haram and ISWA gaining ground and capabilities in Chad.”

The attack on Bohoma raises other important questions such as: which group or groups were responsible for the attack? Who led and organized the assault? And what strategic purpose did it serve? It is hard to offer more than speculative responses to these questions. The Boko Haram contingent operating on the northern shores of Lake Chad, supposedly led by Ibrahim Bakura, is believed to be responsible for the attack on Bohoma. A video of Shekau claiming the attack circulated on messaging services the following day. However, the Nigerien Ministry of Defense had previously claimed to have killed Bakura in a joint Niger-Nigeria operation that took place in their respective territories around the lake from March 10 to 16.

Should this lake faction of Boko Haram be responsible for the Bohoma attack, it would be particularly worrisome since ISWA is widely recognized as the stronger of the two forces operating across the Lake Chad region. Recent leadership tensions within ISWA may have unraveled some of its support, perhaps to Boko Haram’s advantage. Yet, ISWA claimed to have ambushed the Nigerian military near the village of Goniri in Borno State, killing 100 soldiers and militiamen, on the same day as the attack on Bohoma. These events may signal that both groups are gaining support and capability in the wider region.

Response of the Chadian Armed Forces and Operation Bohoma’s Wrath

The response from the Chadian armed forces and government came rapidly. Déby flew to Bohoma personally to witness the damage left behind on the battlefield. He stayed in Lac Province to announce 3 days of national mourning for the 98 fallen soldiers and subsequently launched a military operation called Operation colère de Boma on March 31.

The operation mobilized hundreds of soldiers, including a battalion that had originally been deployed to the Liptako-Gourma region in the central Sahel, where the borders of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso meet. The operation took place across the Kaya and Fouli départments of Lac Province and across their borders into Niger and Nigeria. Both départments were placed under a state of emergency and declared war zones. During the operation, Chadian armed forces systematically cleared the zones using a surge strategy through five sectors to eliminate the presence of militant Islamist fighters from the area.

The operation, which targeted both Boko Haram and ISWA forces, officially concluded on April 9 after Chadian soldiers pursued the remaining militant contingents into Nigerian and Nigerien territory, destroyed their bases, and collected the materiel left behind. Fifty-two Chadian soldiers lost their lives during the operation. Two militant Islamist group command posts were destroyed as part of the operation. Officially, roughly 1,000 militants were neutralized, 58 suspects were taken prisoner, dozens of motorized boats destroyed, and significant arms caches reclaimed. The prisoners were transported to a jail in N’Djamena for further investigation where 44 were later found dead after an apparent mass suicide.

Chadian armed forces in N’Djamena after the end of Operation “Bohoma’s Wrath.” (Photo: VOA/André Kodmadjingar)

In conjunction with the operation, the Chadians deftly deployed a public relations campaign that followed the progress of the military. Photos and video of Déby in military garb discussing the operation with military leaders proliferated on social media and national media outlets during the campaign. The media exposure helped the Chadian government bolster popular support for the operations within Chad.

Déby also used the publicity to pressure the Nigerien and Nigerian forces, complaining that they had not been carrying their weight in the fight against Boko Haram and ISWA and had not sufficiently helped during the operation. He even pronounced a deadline by which Chadian soldiers would withdraw and return to Chad should no Nigerien or Nigerian forces arrive to replace them in their respective territories. When this failed to elicit much response, Déby further antagonized his partners by making comments in Arabic (that were apparently misinterpreted in French), suggesting that Chadian soldiers would no longer participate in any operations outside of their national territory.

The miscommunication provided the Chadian government with a public relations coup. The flurry of analysis and media reporting that explored Chad’s hypothetical withdrawal from all external operations underscored how essential the Chadian armed forces have become to regional security. When the Chadian Ministry of Foreign Affairs clarified Déby’s remarks several days later, it reaffirmed Chad’s commitments to regional security initiatives, namely, the Multinational Joint Taskforce (MNJTF), the Sahel G5 joint force, and MINUSMA (the UN peacekeeping mission in Mali, to which Chad is the largest single contributor with more than 1,400 troops stationed there as of January 2020). In doing so, the importance of Chadian contributions appeared indisputable.

“Unless further steps are taken, it seems likely that Boko Haram and ISWA will adapt and reemerge as they have in the past.”

The show of force from the Chadian military worked to restore the image of Chadian soldiers as a bulwark against militant Islamist groups in the region. It also ratcheted up pressure on armed forces in neighboring countries to more forcefully engage militant Islamist groups. However, unless further steps are taken, it seems likely that Boko Haram and ISWA will adapt and reemerge as they have in the past.

While the Chadian government claims that no Boko Haram fighters remain in Chad following Operation colère de Bohoma, it is difficult to assess how substantially the offensive diminished the capacity of Boko Haram and ISWA in the broader Lake Chad region.

Addressing the Militant Islamist Threat to Chad and the Region

Sustaining the presence of the Chadian (or other regional) armed forces for a lengthy duration is essential for wearing down Boko Haram and ISWA. Insurgencies in weak states that are characterized by difficult terrain, such as those around Lake Chad, are particularly challenging to resolve.

Regional forces have an opportunity to capitalize on the recent Chadian surge by developing a long-term strategy for securing the region. Insurgencies are organizations that can be worn down when faced with sustained pressure. Reaffirming a commitment to holding the territory recently secured by Chadian soldiers should include gathering intelligence on the militant Islamist groups, disrupting their resource streams, and mounting further offensives to dislodge them from new hideouts.

“Insurgencies are organizations that can be worn down when faced with sustained pressure.”

Chad should continue to pressure its regional partners for increased engagement and coordination in the fight against Boko Haram and ISWA. Using public relations to pressure regional partners may lead to greater contributions to—and focus on—their shared security goals. Defeating Boko Haram and ISWA will require contributions and coordination from all the countries of the Lake Chad Basin, lest these militant groups simply shift their bases to the territory of least resistance. This is a reason insurgencies often thrive along border areas and underscores that this is genuinely a regional problem, requiring a regional commitment.

Successful counterinsurgency operations in contexts like the area around Lake Chad must be enduring in order to permanently dismantle insurgent initiatives. After all, insurgents have the advantage in that by simply surviving, they are effectively winning. Regional actors must also recognize that just because conflict persists and the actors engaged continually adapt and evolve, this does not mean counterinsurgency efforts are futile. Rather, the successes and setbacks of any counterinsurgency should be met with recalibrations in strategy and renewed efforts to disrupt, dismay, and ultimately defeat the insurgent groups. The Chadian military has demonstrated the ability to expunge the militant Islamist groups from its territory. Sustaining this success, however, hinges on its ability to coordinate with regional partners and demonstrate its long-term commitment to protect communities around Lake Chad.

Additional Resources

- Remadji Hoinathy, “Is Counterterrorism History Repeating Itself in the Lake Chad Basin,” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, April 15, 2020.

- International Crisis Group, “Behind the Jihadist Attack in Chad,” Commentary, April 6, 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Threat from African Militant Islamist Groups Expanding, Diversifying,” Infographic, January 18, 2020.

- Pauline Le Roux, “Responding to the Rise in Violent Extremism in the Sahel,” Africa Security Brief 36, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 2019.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “David Kilcullen Discusses Counterinsurgency Lessons for Africa,” Video Interview, June 13, 2016.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Lessons for Africa from Colombia’s Counterinsurgency Experience,” Video, March 7, 2016.

More on: Countering Violent Extremism Boko Haram Chad Sahel