A voting station in South Africa. (Photo: GovernmentZA)

Africa is set to host two dozen national elections in 2019. This reflects a now established norm of elections as the recognized means for selecting African leaders. The quality of these elections continues to vary widely, however, with some merely serving as a perfunctory ritual by which leaders maintain their claim on power. Nonetheless, a host of competitive elections will be held in Africa in 2019, including in three of the most consequential democratic experiences underway on the continent—Nigeria, South Africa, and Tunisia.

This variance in the caliber of African elections is part of a longer term process underway since the 1990s to build democratic institutions and consolidate genuinely democratic political systems. This struggle for governance norms has direct security implications in Africa, where virtually all conflicts are intrastate. More than half of Africa’s ongoing conflicts are the direct result of disputed claims over legitimacy, including leaders staying in power past a designated two-term limit.

The conduct and outcomes of the 2019 elections, concentrated in west and southern Africa, will further shape the direction of Africa’s democratic trajectory. Here are some of the key issues to watch.

Click for printable PDF version

Nigeria

Nigeria

General Election, February 23

Africa’s first presidential election of the year may be its most important as the continent’s most populous country and its largest economy and oil producer selects its leader for the next 4 years. Incumbent Muhammadu Buhari of the All People’s Congress faces leading rival Atiku Abubakar of the People’s Democratic Party, as well as 30 other presidential hopefuls in the first round of voting in February.

Security will be a key issue on voters’ minds. Buhari won elections in 2015 on a platform that he could end the Boko Haram insurgency. While the number of attacks and fatalities linked to Boko Haram has declined since a peak in 2015, Boko Haram and a splinter group, the Islamic State of West Africa (ISWA), remain active in the northeast. In 2018, these groups were associated with 483 violent events and 2,297 deaths in the country, contributing to the internal displacement of nearly 2 million Nigerians.

Voting during the 2015 election in Nigeria.

In addition to the militant Islamist group threat in the north, Nigeria is facing security challenges involving growing farmer-herder violence, restiveness among segments of the country’s minority Shiite population, separatist tensions in the southeast, unresolved grievances in the oil-rich Niger Delta region, and growing criminal violence in Nigeria’s rapidly expanding urban areas. Whichever candidate emerges victorious, he will need to devise and sustain alternative approaches in these hotspots where government presence is often lacking and trust in the security services is low.

The 2019 presidential election—the sixth since the end of military rule in 1999—will likewise measure whether Nigeria can maintain the steady improvement in the transparency and credibility of its electoral process. The 2015 elections facilitated Nigeria’s first democratic transfer of presidential power between candidates of opposing political parties. This progress has been greatly facilitated by the active participation of civil society groups assisting with voter registration and maintaining parallel vote counts. This also reflects the heightened expectations of Nigeria’s expanding and increasingly educated youth and middle-class population. President Buhari’s decision to suspend Chief Justice Walter Nkanu Samuel Onnoghen three weeks before the election pending charges that he had failed to declare his assets, consequently, has generated extensive scrutiny.

While violence around both national and state-level elections remains a concern, significant improvements have been realized since the 2011 polls when an estimated 800 Nigerians died in post-election–related violence. How the 2019 elections are managed will demonstrate just how much progress has been made. A process that is seen as fair and transparent will empower the next Nigerian leader with the legitimacy needed to take action on Nigeria’s serious challenges.

Senegal

Senegal

Presidential Election, February 24

In Senegal, President Macky Sall is seeking reelection, vying against four other contenders. This is a significant moment as Senegal has been an anchor of stability in West Africa. With its strong civil society, national identity, professional military, and government responsiveness to public concerns, Senegal has a solid foundation for the democratic progress it has made since its first transfer of power between parties in 2000. Reflective of this, Senegal is one of the few African countries to have never experienced a coup. The 2019 elections are an opportunity for Senegal to continue the consolidation of its democratic norms.

The commitment to upholding democratic processes was reinforced with popular protests in 2012 when then-president Abdoulaye Wade controversially attempted to stay in office for a third term. The commitment to term limits was solidified in a referendum in 2016 championed by President Sall that reduced presidential terms from 7 years to 5.

Senegal’s positive democratic narrative has been tainted to some extent by the 2018 sentencing of leading opposition candidate Khalifa Sall, the former mayor of Dakar, to 5 years in prison on corruption charges. Another potential challenger, Karim Wade, the son of the former president, was found guilty on corruption charges in 2015. He fled to Qatar in 2016 after he was pardoned by President Sall. The charges have prevented these rivals from contesting for the presidency, fueling opponents’ claims that the charges are politically motivated. The cases have prompted thousands to protest against the perceived bias of the Ministry of Interior and Constitutional Court. The strength of support for Macky Sall in this year’s elections will be a measure of whether the public finds Sall’s actions warranted and provide him an endorsement to continue his reform agenda.

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso

Constitutional Referendum, March 24 (postponed)

Burkina Faso’s constitutional referendum, largely focused on establishing a two-term limit for the presidency, is an important step in the institutionalization process needed to advance democracy and, therefore, deserves watching.

The referendum is the outcome of reform efforts led by President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, elected in 2015 following the ouster of long-time autocratic leader Blaise Compaoré in 2014, after 27 years in office. While some have complained over the slow pace of change, the referendum demonstrates a continuity in the reform effort. Democratic transitions often lose steam in the months and years following the ouster of an authoritarian leader. That Burkina Faso has maintained the momentum for reform in the subsequent years is noteworthy as is the fact that it is the sitting president who is presiding over the establishment of these checks on the executive. Further progress is needed in other areas, including protections for civil society leaders such as Safiatou Lopez, who awaits trial on what are widely seen as politically motivated charges after criticizing Kaboré. Nonetheless, the referendum should be recognized as an important step in the sustained and hard-fought efforts needed to create genuine democratic change.

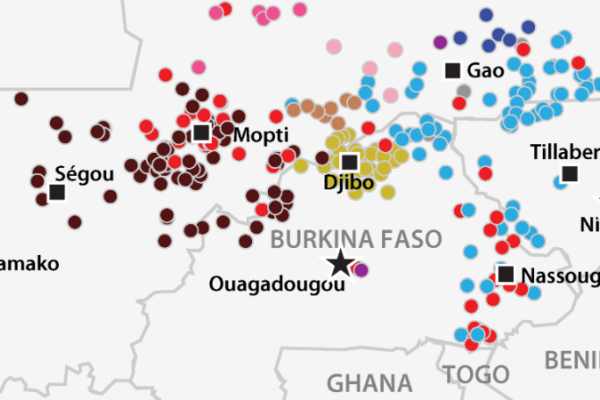

Violent events linked to militant Islamist groups in Burkina Faso and its neighbors in 2018. (Click for larger Sahel map.)

The referendum takes place as Burkina Faso faces a rapidly escalating threat from militant Islamist groups in the north and east. Burkina Faso faced 136 violent incidents involving militant Islamist groups in 2018—a quadrupling of the level seen in 2017. President Kaboré announced a state of emergency in 6 of the country’s 13 provinces on December 31, 2018, in response to the growing threat. The enhanced legitimacy that is likely to result from the referendum will be a valuable rallying force for strengthening citizen support to counter these militant Islamist groups, most notably the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. This will have to be complemented by more effective economic and political engagement of marginalized communities and a strengthening of Burkina Faso’s weak state capacities if the country is to effectively arrest the spread of these violent extremist groups.

Comoros

Comoros

Presidential and Regional Elections, March 24

The presidential and regional elections in the small Indian Ocean islands nation of 800,000 people comes at a time of crisis for the Comoros. In July 2018, President Azali Assoumani secured victory in a controversial referendum boycotted by opposition parties that extended presidential term limits to two 5-year terms. This deviates from the previous practice of rotating the presidency after 5-year terms among the three main islands that comprise the Comoros: Grande Comore, Anjouan, and Moheli. Assoumani suspended the Constitutional Court before the referendum, a move which opposition parties claim was illegitimate.

Comoros has had 20 coups or attempts to seize power since it gained its independence from France in 1975. Nonetheless, the country has made significant progress in regularizing its democratic system of power sharing since it adopted the rotating presidency formula in 2001. The current crisis is a setback to that momentum.

Dozens of opposition leaders have been jailed or fled the country for protesting the 2018 referendum. Azali, who has named all of the judges on the country’s Supreme Court, is accused of employing increasingly authoritarian tactics. The March elections will be a significant test of whether the Comoros can regain its democratic trajectory or return to the instability that has characterized the politics of its early post-independence period.

Algeria

Algeria

Presidential Election, April 18 (Postponed to December 12)

The presidential election in Algeria generated unanticipated drama as the 81-year old President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, in power since 1999, sought a 5th term in Algeria’s tightly controlled political system. Thousands of protesters filled the streets of Algiers and other urban centers demanding Bouteflika step down. Comprising many youth and women, the protests reflect a desire by many Algerians for political reform and modernization that would allow more popular participation in Algeria’s political process.

Bouteflika, who has won the last four elections with an average of 83 percent of the vote, has rarely been seen in public since experiencing a stroke in 2013. The military has been tightly intertwined in Algerian politics for many years, and Bouteflika’s ruling National Liberation Front party retains strong support from the military and business elite. A purging of a number of top military commanders in 2018 allowed military leaders to further consolidate their power in advance of the election.

South Africa

South Africa

General Election, May 8

Another touchstone election for the continent will be South Africa’s general and parliamentary elections, from which the president will be selected. As one of Africa’s leading economies and advanced militaries, the elections in South Africa will have ramifications for the rest of the continent.

In many ways, the South Africa polls will be an election within an election. The ruling African National Congress (ANC) remains the dominant political party in the country. The question that will be answered at the polls is whether, after a series of corruption scandals, growing urban crime, and perceptions that the ANC has lost touch with ordinary South Africans, the ANC still commands sufficient trust among a majority of the population. In municipal elections in 2016, the ANC suffered its worst electoral defeat since the end of apartheid when it lost control of many cities, including the political and business capitals, Pretoria, and Johannesburg, the legislative capital, Cape Town, and the industrial city of Port Elizabeth.

Cyril Ramaphosa. (Photo: ITU Pictures)

The ANC has made significant course corrections since then with the replacement of former party leader and president Jacob Zuma with Cyril Ramaphosa at the ANC National Conference in December 2017. Ramaphosa has moved decisively to distance the party from many of the abuses of power associated with Zuma by instituting a series of reforms to reinstate more transparency in party and government practices. Through these actions, South Africa demonstrated that its system of democratic checks and balances was strong enough to rein in a populist leader willing to test the limits of the rule of law.

Nonetheless, many in the ANC who benefited under Zuma’s patronage have resisted Ramaphosa’s reforms. These elections will be a referendum on the ANC’s current direction. If Ramaphosa wins with a strong majority, he’ll be empowered to push forward with additional reforms. If not, he may be forced to make further concessions to the Zuma wing in the ANC.

Another storyline to watch is the ongoing transformation of a liberation movement. Having led South Africa in its opposition to and transition from apartheid, the ANC enjoys deep loyalty among many South Africans. Yet, as with other liberation movements in Africa, such loyalty may create among party leaders a sense of entitlement, a disincentive to pursue reforms, and the space for abuse of power. The 2019 elections will be an important juncture in this process, helping to answer the question of whether the ANC is capable of undertaking fundamental reforms itself or whether genuine reform must wait for an opposition party to gain power nationally.

There are also important regional security implications from the elections in South Africa. Under Ramaphosa, South Africa has begun reasserting its leadership within the Southern African Development Community and the African Union on issues of conflict resolution and upholding democratic norms in regional crises. These policies, as well as its position as a standard bearer for the protection of human rights, have been associated with South Africa since the presidency of Nelson Mandela but had lapsed under Zuma. The former president’s allies have resisted Ramaphosa’s reassertion of these foreign policy initiatives, underscoring the regional consequences from the South Africa elections.

Photo: Darryn van der Walt.

Malawi

Malawi

General Election, May 21

Malawi’s general elections (for President, National Assembly, and local government officials) are gearing up to be a hotly contested affair as President Peter Mutharika of the Democratic Progressive Party seeks a second term. He faces stiff opposition from an array of candidates including his vice president, Saulos Chilima, Lazarus Chakwera of the Malawi Congress Party, and former president Joyce Banda’s People’s Party. The shifting coalitions of opposition parties attempting to unite to defeat Mutharika make this a highly fluid electoral environment.

Given that Malawi’s major political parties all draw significant popular support, the winner is likely to only command a plurality of voters—as occurred in 2014. This underscores the importance of the proposed reform to adopt a 50 percent-plus-one formula for selecting the president. Parties would then have incentives to build more encompassing coalitions and electoral winners could then benefit from the legitimacy earned from having the support of a majority of citizens.

The 2014 election marked the milestone of an opposition party taking power through a peaceful transition. That election was consistent with Malawi’s reputation for stability and built on the upholding of term limits in place since 2003. Charges of corruption, nepotism, and anticipated vote-rigging have contributed to a volatile atmosphere in the lead up to the May elections, however. How well Malawi’s Electoral Commission manages the 2019 electoral process will provide a yardstick for the rate of institutional progress in one of southern Africa’s historically most stable countries.

Mauritania

Mauritania

Presidential Election, June 22

Another noteworthy transition on the continent will be in Mauritania, when the West African country selects a new leader to replace incumbent President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz who is stepping down after two terms, as required by Mauritania’s constitution. He will do so despite many in his party encouraging him to remain for a third term. It would also mark a significant departure from Ould Abdel Aziz’s entry onto the political arena as the force behind the 2005 and 2008 coups. (He was subsequently elected in non-competitive polls in 2009 and again in 2014.)

Mauritanian anti-slavery advocate Biram Dah Abeid. (Photo: US Mission Geneva)

As Ould Abdel Aziz’s Union pour la république ruling party commands a dominant parliamentary majority, observers speculate that Ould Abdel Aziz could still wield considerable power from behind the scenes after the vote. Ould Abdel Aziz is supporting Defense Minister Mohamed Ould Ghazouani as the ruling party’s presidential candidate in 2019. Moreover, the constitution allows the 62-year-old president to run again in 2024. Nonetheless, Ould Abdel Aziz’s willingness to work within Mauritania’s fledgling democratic process is a notable departure from other African leaders of recent years who have maneuvered to evade term limits.

Mauritania has much progress to make in strengthening its civil-military relations given a legacy of strong military leaders. Protections for civil liberties and a free press are also still in a formative stage. The arrest and 5-month detention of leading anti-slavery advocate Biram Dah Abeid in 2018 is illustrative of the limitations that persist in Mauritania’s political system. Dah Abeid was nonetheless elected to parliament during his detention and has declared his intention to contest for the presidency in 2019.

Tunisia

Tunisia

Presidential Election, September 15, October 13 (second round)

Parliamentary Election, October 6

One of the most anticipated elections of the year will be when Tunisia holds its third round of national elections since the ouster of longtime autocratic leader Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011. The elections mark another milestone in the democratic transition of the one North African country that has been able to sustain momentum for reform following the Arab Spring protests. Tunisia has been noteworthy in that it has comprised a multiparty process of competing political visions willing to work together within a democratic framework. This includes the Islamist Ennahda party, providing a model for the compatibility of Islamist parties and democracy.

Campaigning in 2019 will reflect new coalitions from the last national elections in 2014. While Ennahda retains a broad base of popular support, their erstwhile coalition partner, the secularist Nidaa Tounes party, has been riven by divisions since the installation of the late Hafedh Essebi, the son of 92-year-old President Beji Caid Essebi, as party leader. This has led some members, led by Prime Minister Youssef Chahed, to form a new party, the National Coalition. With no party commanding a majority, the need to compromise will continue to characterize Tunisian politics around priorities of unemployment, inflation, security, and issues of identity, especially the role of religion and women in public life.

Tunisia’s democratic experience hasn’t been without violence. There have been several high-profile assassinations, and the risk of political violence has not fully receded. The 2019 elections, therefore, will be an important test in the consolidation of non-violent norms to resolve political differences in Tunisia.

Tunisians protesting against terrorism.

Tunisia also still faces security risks of returning ISIS fighters from Iraq and Syria. It is estimated that some 7,000-8,000 Tunisians joined ISIS at the height of its ascension in 2014-2015. Worries that these fighters would return and provoke instability, including the possibility of an ISIS affiliate in Tunisia, have persisted since. Tunisia has avoided the worst of this predicament thus far, with violent events linked to militant Islamist groups remaining limited in recent years. In 2018, there were 36 such episodes and even fewer fatalities. This compares to 2015, when ISIS attacks at a resort in Sousse and the Bardo Museum contributed to 154 fatalities related to extremist violence in Tunisia that year.

Sharp socioeconomic disparities and perceptions of marginalization in parts of Tunisia have created ongoing restiveness and protests, especially among the youth. Such perceptions of systematic grievance, moreover, create a potentially fertile social environment for recruitment by militant groups. Responding to these social disparities within a framework of economic austerity adopted as part of a $2.8-billion loan from the International Monetary Fund will be a focal point of the 2019 campaign.

Mozambique

Mozambique

General Election, October 15

Presidential, parliamentary, and provincial elections are expected to take place in Mozambique in a complex political environment. Building on a 2016 ceasefire, peace talks between the ruling FRELIMO party and longtime rebel and opposition party RENAMO aim to negotiate an end to a low-intensity conflict that resurfaced in 2013. The elections also take place before a backdrop of perceptions of political exclusion by opposition parties, especially RENAMO, which will be contesting its first election without longtime leader Afonso Dhlakama, who died in 2018. FRELIMO has controlled the presidency and dominated Parliament since the end of the country’s brutal civil war in 1992. This has generated strong grievances and periodic violence since 2013 over the lack of genuine participation.

In addition to the simmering grievances, the government is still reeling from the damage to Mozambique’s international reputation following the $2 billion scandal involving government diversions of loans and subsequent default. Moreover, it is seeking to develop natural gas deposits in the increasingly unstable north of the country. Accordingly, FRELIMO has an incentive to boost its legitimacy in the 2019 electoral process. Signs of this were seen in the 2018 municipal elections, where RENAMO competed for the first time in 10 years and made gains.

President Filipe Nyusi is competing for a second and final term. Securing a peace deal with RENAMO and integrating its remaining fighters into the armed forces will allow him to shore up stability in RENAMO’s northern and central strongholds. Mozambique is also facing militant Islamist violence taking root in the north, support for which has been augmented by heavy-handed and arbitrary responses on the part of Mozambican security forces. In short, lack of transparency, abuse of power, and a sense of entitlement has hindered robust checks and balances in Mozambique.

The 2019 elections will provide a test of whether the government is committed to building a more inclusive (and stable) democratic process. In this way, FRELIMO faces the challenge of other African liberation movements that have struggled to become genuine governing bodies advancing the needs of all citizens. The answer to these questions will go a long way in shaping the depth of solidarity Mozambicans feel as they face a series of new security, development, and political challenges while renewing international engagement.

Botswana

Botswana

General Election, October 31

One of Africa’s strongest democracies and, arguably, its most stable, will have its next general elections in October. Botswana’s stability is closely linked to its succession process, the precedent of which was established by Festus Mogae in 2008 at the end of his second term. President Mokgweetsi Masisi will contest in the October elections as part of the ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP).

Masisi succeeded former president, Ian Khama, as party leader in April 2018 as Khama, having already served 10 years in office, was nearing the completion of his second term. Underscoring the perennial difficulty of stepping down from power faced by many leaders, Khama had flirted with trying to extend his time in office. However, Botswana’s resilient democratic traditions prevailed upon Khama to abandon this consideration, maintaining Botswana’s succession tradition.

Botswana is the exceptional democracy that has never had a transition in power between parties.

Botswana is the exceptional democracy that has never had a transition in power between parties. The BDP has held a parliamentary majority since Botswana’s first post-independence elections in 1969. The party has, however, upheld various means of accountability that have enabled it to maintain the trust and popular support of the general population. These include a free press, an apolitical security sector, independent financial institutions, and an autonomous investigative body. Botswana is regularly rated among Africa’s most transparent countries on Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index.

Recent elections have become more competitive, moreover, with the BDP winning just 37 of 57 seats in the National Assembly in 2014. As opposition parties further build their base of constituents, a transition of power to another party is a reasonable prospect in the not too distant future.

Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau

Presidential Election, November 24

The presidential election in Guinea-Bissau is scheduled for November 24th following four years of dispute over the appointment of prime minister who can lead the government. Guinea-Bissau’s ruling party, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), has struggled with internal rivalries since the current president, José Mário Vaz, dismissed former prime minister and head of PAIGC, Domingos Simões Pereira in 2015. The political crisis has restricted the government’s ability to provide basic services to citizens and address widespread economic discontent marked by service protests. Schools have been closed across the country for months due to a teacher’s strike.

ECOWAS engagement in three rounds of high-level talks led to peaceful legislative elections in March 2019. The parliamentary elections were supposed to mark an important breakthrough in the crisis, but infighting between the PAIGC and Vaz continued to stall progress in the formation of a new government. Eventually, after two more mediation missions led by ECOWAS and under the threat of sanctions, Aristides Gomes was named the consensus prime minister in June, just as Vaz’s term as president was ending. As part of the deal, ECOWAS declared that Vaz may remain president until the November 24 presidential elections. However, just weeks before the election, Vaz fired Gomes and appointed Faustino Imbali as prime minister, reigniting a political stalemate in which Guinea-Bissau has had 8 prime ministers since Vaz took office in 2014. ECOWAS has deemed the firing of Gomes illegal and continues to recognize him as the rightful prime minister.

Voters will choose between Vaz who is running for reelection on an independent ticket, and former prime ministers Carlos Gomes Jr. and Domingos Simões Pereira.

Namibia

Namibia

General Election, November 27

The South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO) party has dominated Namibian politics since independence from South Africa in 1990. This pattern continues today with SWAPO controlling 77 of 96 seats in the National Assembly. Incumbent President Hage Geingob, similarly, won office in a landslide with 87 percent of the popular vote in 2014. He is seeking his second term in a crowded field of 15 candidates.

As Namibia has yet to experience a transition of power between parties, some questions remain over the robustness of its checks and balances. Nonetheless, Namibia has realized considerable strengthening of its democratic institutions over the years. This maturing of the political system is seen in the adherence of presidents to term limits, the precedent of which was established with Namibia’s second president, Hifikepunye Pohamba, who stepped down in 2015. Further institutionalization of the democratic process is seen with a strengthening civil society and the growing independence of the press, government oversight mechanisms, and the private sector. In this way, Namibia provides a positive model of a liberation movement party taking meaningful steps to transition to democracy.

Namibia’s political stability has made it an anchor for governance and security issues in southern Africa—a pattern that is expected to continue after the 2019 elections.

More on: Democratization Algeria Botswana Burkina Faso Comoros Malawi Mauritania Mozambique Namibia Nigeria Senegal South Africa Tunisia