A woman voting in Sierra Leone in 2018. (Photo: USAID/Carol Sahley)

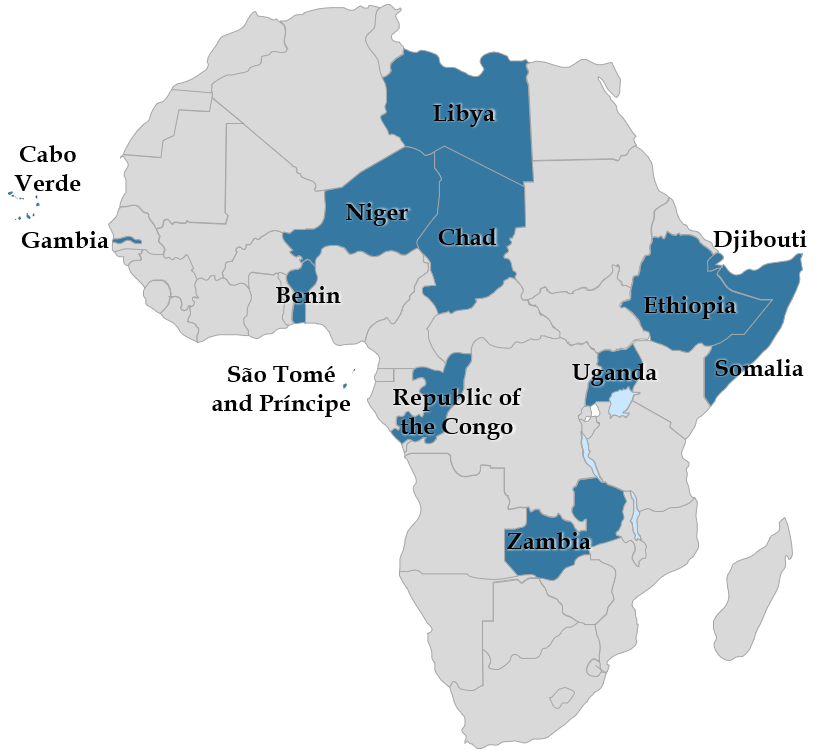

Africa is slated to hold 13 national elections in 2021. Roughly half of these are in the Horn and the central Sahel. Reflective of the democratic backsliding observed on the continent in recent years, more than a third of these polls are little more than political theater – aimed at garnering a fig leaf of legitimacy for leaders who arguably lack a popular mandate. Leaders attempting to circumvent term limits are a prominent feature in this year’s line-up, shaping nearly half of the elections, and showcasing some of Africa’s longest standing heads of state. A small but growing number of incumbents are likewise banning opposition parties, or criminalizing critical media reporting, to clear the electoral playing field.

A fundamental question for this year’s elections, therefore, isn’t just about who will win, but how these leaders will be viewed afterward. Will the same level of legitimacy be conferred on leaders who stay in office via these stage-managed processes? Until these leaders bear a reputational cost for lowering the bar of electoral integrity, this trend can be expected to continue.

Security is closely tied to issues of legitimacy and electoral integrity. Five countries undertaking elections this year are facing armed conflict (Chad, Ethiopia, Libya, Niger, and Somalia). The legitimacy these leaders may gain by winning popular endorsement can be a powerful tool for navigating these conflicts. Conversely, perceptions that entrenched leaders cannot be removed constitutionally via the ballot box will likely only fuel the grievances that lead to more violent forms of confrontation.

Not to be overlooked, there are a number of cases where leaders are stepping down at the end of their designated terms. These elections deserve attention in their own right as well as for the norms they reinforce.

Here are some of the key issues to watch:

Uganda

Uganda

Presidential and Legislative Elections, January 14

Uganda’s January 2021 presidential election process has been defined by the increasingly blatant use of violence by Ugandan police and armed forces to ensure that 76-year-old President Yoweri Museveni retains his 35-year hold on power. Museveni is seeking his sixth term in office following the removal of presidential age limits in 2017 and term limits in 2005 that would have required him to step down. While 11 opposition candidates have been certified by the Electoral Commission, they have been repeatedly detained, threatened, and blocked from campaigning. Opposition supporters attempting to attend rallies have been harassed and beaten, and at least 55 have been killed.

The increased intimidation reflects a judgement by the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) that such tactics are necessary to deny the opposition an opening that could imperil the party’s long dominance. Drawing on its identity as a national liberation movement, the NRM has been increasingly inclined to define political rivals as the enemy, rationalizing the use of force. With an estimated $300 billion in revenues from Uganda’s 6 billion-barrel oil reserves set to begin flowing in 2022, the NRM has further incentives to hold onto power.

Ugandan presidential candidate Bobi Wine being arrested in January 2020. (Image: VOA/Screen capture)

The heavy-handed response to this election by the NRM also reflects the threat party leaders feel from Uganda’s increasingly mobilized youth. Seventy-eight percent of Ugandans are under the age of 35, meaning they were born after Museveni came to power. They aspire for more genuine democracy and are vocal about the perceived growing corruption of the NRM, which is seen as directly responsible for the limited jobs available for young people. They reject the NRM’s claim on perpetual entitlement. The face of these aspirations is reggae star-turned-legislator Bobi Wine, and his People Power movement, who has made issues of injustice a cornerstone of his message.

The opposition faces a highly tilted playing field, however. The January 14 date for the elections was moved up by 3 months to shorten the campaign season, further limiting opposition parties from mobilizing their supporters. The Electoral Commission, moreover, has failed to implement significant reforms following the flawed 2016 elections, despite rulings from the Supreme Court that they do so. In January, Museveni took the unprecedented step of formally inserting UPDF Joint Staff and division commanders into the electoral process by deploying them to oversee security operations around polling stations, mainly in urban areas.

Opposition complaints over bias within the Electoral Commission mirror the growing politicization of other key institutions. These are supported by a bevy of legal instruments such as the Public Order Management Act, Communications Act, Preventative Detention Act, and Stage Play and Entertainment Rules, which have been used to arrest opposition leaders, block peaceful protests and opposition rallies, and detain journalists.

Opposition presidential candidates have also been restricted from meeting with the media, forcing candidates to rely on supporters to speak to the press. A daily tax on social media instituted in 2020 requires that all users of social media obtain a license and agree not to engage in “distortion of facts” or put out content “likely to create public insecurity,” something Amnesty International has characterized as criminalizing the right to freedom of expression online.

“Ugandans have never experienced full political participation during Museveni’s rule.”

Despite these challenges, Uganda’s civil society and professional organizations have been resilient in their efforts to uphold their democratic rights. Two electoral petitions are already before the courts alleging violations of the electoral law and constitutional rules. Voting apps have also been created to enable voters to track results in real time and help substantiate claims of voter fraud.

While Ugandans have never experienced full political participation during Museveni’s rule, the country has been recognized for its relative respect of civil liberties. These civil liberties have been substantially diminished during the 2021 electoral cycle, moving Uganda further away from the democratic aspirations of many of its citizens.

Niger

Niger

Presidential Election, February 21

None of the 28 candidates competing in Niger’s December 27, 2020 presidential election were able to secure a majority, precipitating a second-round run-off between the two top vote getters. Interior Minister Mohamed Bazoum of the ruling Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism won 39 percent of the first-round vote, and former president Mahamane Ousmane of the Democratic and Social-Convention-Rahama party came in second with 17 percent.

Bazoum, who was previously foreign minister, is a teacher by training and has campaigned on a platform of security and education. His party is also expected to hold a parliamentary majority when final tallies from the December 27 vote are completed. Ousmane was Niger’s democratically elected president from 1993 until 1996 when he was ousted in a military coup. He was later speaker of the ECOWAS parliament from 2006 to 2011 and was a staunch opponent of President Tandja Mamadou’s efforts to extend his two terms in office in 2009.

“President Mahamadou Issoufou is stepping down following his second 5-year term in office, thereby setting a valuable precedent.”

Whichever candidate wins, the election is a milestone for Niger, as it will be the first democratic transfer of power this country of 22 million people has experienced. President Mahamadou Issoufou is stepping down following his second 5-year term in office, thereby setting a valuable precedent of upholding term limits and helping to institutionalize this important check on executive power.

Niger is undertaking this democratic transition while combating an increasingly aggressive set of insurgencies from militant Islamist groups. These attacks are occurring in two separate theaters. The first, largely perpetuated by the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, is concentrated in the west along the borders with Mali and Burkina Faso. The second is in the Lake Chad region and involves Boko Haram and its offshoot, the Islamic State of West Africa. Altogether, Niger faced over 250 violent attacks and 929 fatalities involving militant Islamist groups in 2020. This represents a 22 percent increase in events from the previous year and a 13-fold surge since 2017. While Niger has experienced relatively lower levels of violence than its Sahelian neighbors Mali and Burkina Faso, it continues to sustain significant losses of both security personnel and civilians. These attacks have restricted movement and commerce, creating additional burdens on the economy of one of the poorest countries in the world.

A pressing priority facing the winner of the February run-off thus will be mobilizing a broad-based strategy, involving local communities and regional partners, to reverse the trend of militant Islamist activity.

⇑ Back to Top ⇑

Republic of the Congo

Republic of the Congo

Presidential Election, March 21

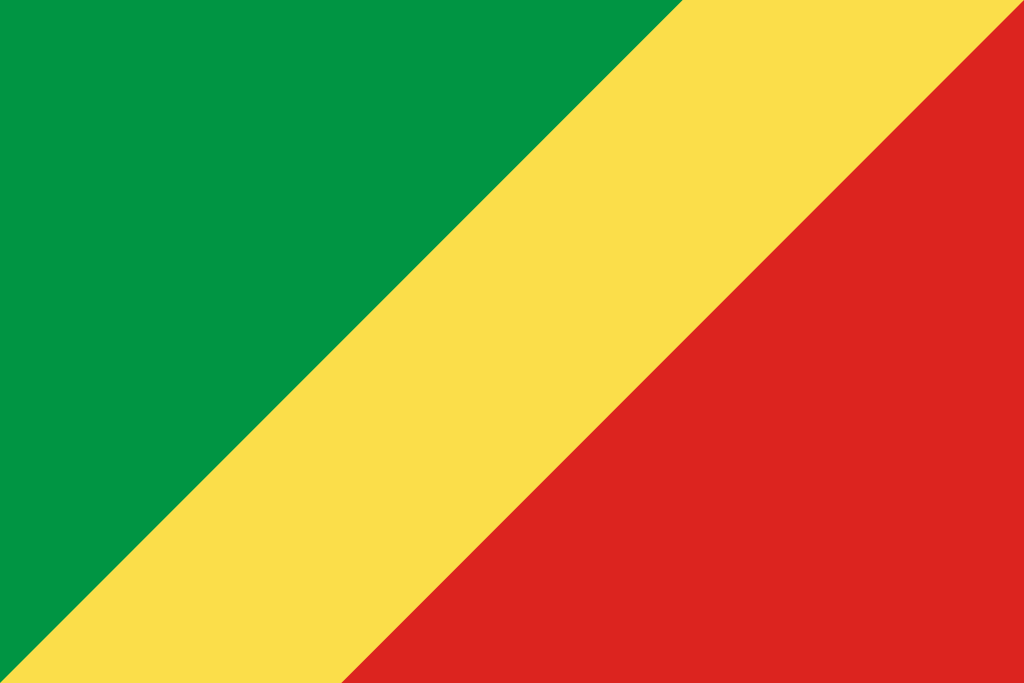

The Republic of the Congo’s presidential election is expected to generate little drama in what is shaping up as a highly orchestrated ceremony, rather than a competitive election. The incumbent, 77-year-old Denis Sassou Nguesso, and the ruling Congolese Party of Labor (PCT), have a firm hold on the levers of power, which they are intent on retaining following the March proceedings. Reflective of the lack of seriousness afforded to the electoral process, Electoral Commission members were only identified in December 2020 and voter registration remains far behind schedule.

President Denis Sassou-Nguesso. (Photo: mediacongo.net)

The key storyline of this cycle is Sassou Nguesso’s longevity, with 2021 marking his 37th year as head of state of this hydrocarbon-rich central African state, making him Africa’s third longest serving leader. This would be his fourth consecutive term since returning to power in 1997 and his sixth term overall, having previously held the presidency from 1979 to 1992. A constitutional revision in 2015 did away with age limits (which would have disqualified Sassou Nguesso), extended presidential term limits to 3 terms (which do not apply to the incumbent), and reduced terms from 7 years to 5.

Sassou Nguesso has relied on political intimidation and repression to remain in power. In 2019, former presidential candidate André Okombi Salissa was sentenced to 20 years of forced labor on charges of threatening state security. A similar charge was levied in 2018 against another candidate, retired general Jean-Marie Michel Mokoko, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Media operating in the Congo are required to register with the Orwellian-sounding regulatory body, the Superior Council for Liberty and Communications. Outlets that violate Council regulations are subject to financial sanctions or closure, resulting in a high degree of self-censorship.

“The trappings of democracy are on display, however, power remains firmly in the control of the ruling party.”

In effect, electoral proceedings in the Republic of the Congo reflect those of a modern African authoritarian state where the trappings of democracy are on display, however, power remains firmly in the control of the ruling party. Elections are held but are not competitive, with the leader facing little accountability. Opposition parties are allowed but unable to challenge the ruling party that, with its allies, controls 108 of 151 (72 percent) of legislative seats. Independent media outlets operate but they are subject to sanction if they are critical of the government.

Consistent with the lack of checks and balances, the Republic of the Congo is widely viewed as corrupt, ranking 165 out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index. This profligacy has resulted in external debt of $6.77 billion, or roughly 119 percent of its GDP. This includes $2.2 billion to Chinese creditors.

While the Republic of the Congo has avoided the debilitating civil conflict that has afflicted other countries in the region, notably the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Cameroon, its ongoing stability cannot be assured. Some of the same factors that are driving conflict in these countries could take hold in the Congo. Underscoring this point, election irregularities surrounding the 2016 presidential election triggered unrest in Brazzaville and attacks on the main rail line linking the capital and the main port at Pointe-Noire.

⇑ Back to Top ⇑

Djibouti

Djibouti

Presidential Election, April 9

President Omar Guelleh is planning to extend his tenure to a fifth term in Djibouti’s presidential elections that are not expected to be free or fair. The 73-year-old leader, whose patronage-based rule relies on military support for his regime, has been in power since 1999. Term limits were lifted in 2010, prior to Guelleh’s third term, even though he had said in 2005 that he would only serve two terms as stipulated by the constitution.

During his tenure, Guelleh has increasingly relied on repressive tactics to limit dissent. Opposition parties must be “recognized” by the partisan electoral commission, affording considerable leverage over which parties can participate. Even among recognized parties, members are periodically harassed, arrested, and prosecuted. Criminal records, in turn, can disqualify candidates from running.

State media dominates public discourse and no privately owned or independent media operates within the country. The few journalists who write stories critical of the government are often arrested, beaten, and imprisoned. A vivid illustration of this was the filming in June 2020 of a peaceful protest in support of Air Force officer Fouad Youssouf Ali, who had sought political asylum in Ethiopia after denouncing discrimination and corruption at home. He was subsequently extradited back to Djibouti. A video posted to social media showed that he was being held in degrading conditions, triggering the protest. Police stormed the protest, using live ammunition on those assembled. Journalists who attempted to cover the event were also beaten and arrested.

La Voix de Djibouti broadcasts from Belgium but its signal is often jammed and its website blocked by the authorities. While Internet access is growing and social media is one of the few spaces that enables free speech and allows the press to operate, the government is increasingly trying to limit broadband access. Djibouti ranks 176 out of 180 countries on Reporters Without Borders’ 2020 Press Freedom Index.

“Djibouti faces little international pressure to open its political process and hold genuinely competitive elections.”

Lacking much democratic space, opposition candidates are not in a position to competitively contest the elections. In September 2020, several opposition parties joined together under the banner of the USN Coalition aimed at blocking a fifth Guelleh term. They are proposing a delay in elections until the Election Commission is reformed (something the government had agreed to do in 2015). In the interim, the opposition is calling for a transitional government.

Djibouti faces little international pressure to open its political process and hold genuinely competitive elections because of its strategic location near the Bab al Mandeb and its access to maritime traffic through the Indian Ocean and into the Red Sea. Djibouti hosts naval bases of France, the United States, China, and Japan. It is also the operational base for the international anti-piracy coalition operating in the region.

Royalties from the port and basing fees represent major sources of government revenue. Still, Djibouti has taken on external debt of 103 percent of GDP to support rail, port, and power projects. More than half of this debt is owed to Chinese creditors. Debt service payments have increased by 120 percent between 2019 and 2021 (80 percent of which goes to China), leaving Djibouti in high risk of debt distress.

Djibouti’s economic growth is not well distributed, generating high levels of inequality. Poverty remains at an estimated 36 percent and unemployment at 48 percent. Youth unemployment is particularly high, fueling increased discontent. An armed opposition movement, the Front for the Restoration of Freedom and Democracy, engages in periodic clashes with the Djiboutian armed forces and attacks on state assets.

Benin

Benin

Presidential Election, April 11

Benin’s presidential elections are part of a gambit by President Pierre Talon to normalize political exclusion as a means of perpetuating his hold on power. The inflection point for the current context was April 28, 2019—Benin’s last National Assembly elections, when only two parties loyal to Talon were allowed to run. Béninois largely boycotted the elections resulting in only 27 percent turnout, which international observers deemed a sham. Protesters marched to voice their discontent. The military responded with live ammunition, killing at least four people, in this normally highly stable country.

President Patrice Talon. (Photo: Government of India)

The move to exclude political opponents from participating, a reversal from Benin’s decades-long democratic norms, is an emblem of Talon’s governance style. Believed to be Benin’s richest man prior to taking office in 2016, he has sought to weaken democratic checks and balances to deepen and extend his hold on power. Soon after coming into office, he tried in 2016 and 2017 to remove Benin’s two-term presidential limit in the National Assembly, only to be denied. He has stacked the Constitutional Court and Autonomous National Electoral Commission with loyalists, required parliamentary candidates to be “sponsored” by already elected officials, and charged potential political rivals with crimes, effectively barring them from running.

An aggrieved citizen took the case of political exclusion from the 2019 legislative elections to the regional African Court of People’s and Human Rights (ACPHR). In November 2020, the Court ruled that the constitutional amendments used to exclude opposition parties violated the African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance, to which Benin is a member. The ACPHR ordered Benin to annul the amendment and revert to the previous status quo. There are at least 28 pending cases regarding Benin before the ACPHR, brought by Béninois who feel they cannot find remedy in Benin’s increasingly partisan courts. Resistant to such regional accountability, Talon is withdrawing Benin from the ACPHR.

The April 2021 presidential elections are shaping up to be more of the same. Leading opposition candidates entrepreneur Sebastien Adjavon, former prime minister Lionel Zinsou, and former minister Komi Koutché have all had politically motivated charges filed against them and are now living in exile or otherwise barred from running. These actions effectively remove all serious challengers from Talon’s path to stay on for a second term.

Journalists who have reported critically on Talon have been harassed, threatened, and imprisoned. This is a stark contrast from the open media environment Benin had long enjoyed. A 2016 digital media law included provisions restricting press freedom and criminalizing normal activities of the press, like criticizing government officials. In July 2020, the High Authority for Broadcasting and Communication ordered the closure of all “unauthorized” online media outlets. Benin has dropped 38 places, from 75th to 113th, on Reporters without Borders’ annual Press Freedom Index since Talon came to power.

“The move to exclude political opponents from participating … is an emblem of Talon’s governance style.”

That Talon is intending to stay in power by stacking the electoral deck in his favor appears clear. The more profound question for Benin and West Africa is how will ECOWAS and the international community respond? If it accepts an electoral result where all viable candidates are blocked, protesters are denied the right to assemble, and independent journalists arrested, ECOWAS would be establishing a very low bar for what is deemed an election in West Africa. Doing so would also solidify ECOWAS’ retrenchment from upholding democratic norms in the subregion, despite the mandate in its charter to do so and the subregional body’s exemplary record on this front over the years.

The response from ECOWAS and the international community is particularly meaningful given Benin’s legacy as a democratic pioneer in West Africa since the early 1990s. These democratic norms remain strong within society even though Talon has been able to circumvent the democratic institutional checks and balances on the executive. Should Benin slip back into blatantly authoritarian practices decades after starting down a democratic path without a tangible response from ECOWAS and international democratic actors, the signal to other would-be authoritarians would be crystal clear. In effect, the 2021 election will shape which of Benin’s historical trajectories it will follow moving forward. Given Benin’s role as democratic flag-bearer in the region, what happens there will create ripple effects for democratic norms in Africa that extend far wider than its size.

Chad

Chad

Presidential Election, April 11

Legislative Election, October 24 (postponed)

Chad’s presidential election is expected to be a largely ceremonial affair given the highly limited space for the political opposition to operate. Reflective of the government’s casual attitude toward elections, the leadership and staff of the Independent National Electoral Commission have yet to be identified.

President Idriss Déby. (Photo: Rama)

President Idriss Déby is seeking his sixth term in office, having previously overseen the removal of term limits in 2005 and then their restoration in 2018—though they are not to be applied retroactively. The 68-year-old former military leader came to power in 1990 following the toppling of the despotic Hissène Habré.

Déby is one of Africa’s least constrained presidents, effectively controlling the other branches of government, the security sector, and the media. Legislative elections have been repeatedly delayed and were last held in 2011. Déby eliminated the position of prime minister in 2018, further consolidating his power. While opposition parties are tolerated, they operate on a tight leash. When opposition parties tried to hold a “Citizens Forum” in October 2020 independent of the government’s “Inclusive National Forum,” the police surrounded the headquarters of the responsible opposition parties to prevent the meeting from taking place.

Media is also tightly controlled. Journalists who have covered protests or reported critically on the government have been expelled, detained, or their outlets shuttered. In February 2018, journalists staged a “Day without Press” to denounce police attacks on journalists. A month later, authorities blocked access to social media, which was not restored until July 2019, totaling 470 days. A media training event in November 2020 was raided by police, resulting in 70 arrests.

“Déby is one of Africa’s least constrained presidents.”

Chad’s economy is heavily dependent on oil revenues, which have buoyed the country’s economic growth over the years and constitute 80 percent of export revenues. Nonetheless, these revenues have not been used for development. Forty-seven percent of the population lives in poverty and Chad ranks 160 out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

Chad is widely regarded for having among the most capable militaries in the Sahel and plays a key role in regional counterterrorism campaigns, including the G-5 Sahel, for which Chad will hold the rotating presidency in 2021. Chad is also actively engaged in confronting incursions from Boko Haram militants crossing Lake Chad from Nigeria into Chad’s western Lac Region.

Despite the apparent stability of Déby’s three-decade long rule, Chad remains a highly unstable country with a domestic armed opposition, periodic rebellions, and coup attempts. This includes armed resistance movements based in Libya and Sudan, in part composed of Déby’s own family members and ethnic Zaghawa. This instability can be expected to persist given Chad’s growing inequities, limited opportunities, and lack of political space.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Parliamentary Elections, June 5 (Postponed to June 21)

Perhaps Africa’s most momentous election in 2021 will be when Ethiopians go to the polls in June. Originally scheduled for August 2020, Parliament has delayed the election twice. The first time, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the second, due to logistical challenges. The decision by Tigrayan leaders to go ahead with provincial elections in September set up a confrontation with the federal government that escalated into a full-blown armed conflict in November. The unresolved implications of the Tigray fighting casts a shadow over and underscores the fragility of Ethiopia’s nascent electoral process.

The vote in Ethiopia would be the country’s first genuinely competitive multiparty elections—a historic moment for the country of 100 million people. This democratic opening has been created by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who upon taking the mantle of the premiership in April 2018, opened Ethiopia’s erstwhile tightly controlled political system. The elections thus present an opportunity for popular participation and representation that Ethiopians have long been denied over decades of successive authoritarian governments.

“A strategic subtext to Ethiopia’s election is finding an appropriate balance of power sharing between the regions and the federal government.”

This legacy of authoritarianism and the lack of democratic precedents greatly adds to the complexity of these elections. Democracy-building is more than a single event but will require creating a democratic culture, a years-long effort. Recognizing this, Ethiopia’s 2021 electoral process must navigate multiple treacherous challenges simultaneously, any one of which would be a major obstacle on its own.

Key among these is ensuring the integrity of the process. Given the years of authoritarian rule, coupled with uncertainty and fears of exclusion, Ethiopia’s election is beginning with a high level of distrust. Formerly exiled opposition leader Birtukan Mideksa is the head of the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE), providing a welcome sign of assurance to wary opposition parties. More than in other contexts, it will be vital that the NEBE keep all parties well informed, apply rules even-handedly, accommodate independent electoral observers, and maintain a transparent process for vote counting.

Also key for the integrity of the process is maintaining the free flow of information. Ethiopia has a reputation for regular internet shutdowns, especially during politically sensitive moments. The government, likewise, instituted a strict media blackout during the conflict in Tigray, creating a gulf of information and fueling myriad rumors about what was occurring. Without integrity, the electoral process will lose the legitimacy-enhancing benefit it is intended to produce and, instead, could be a destabilizing event.

Another strategic subtext to Ethiopia’s election is finding an appropriate balance of power sharing between the regions and the federal government. A federal governance structure is well suited for Ethiopia’s large and diverse population to adapt policies to local circumstances and facilitate more government responsiveness to citizen priorities. However, lacking a clear division of responsibilities, federal models can amplify centrifugal pressures on the state as regional leaders have strong incentives to prioritize parochial over national interests. The Abiy government, moreover, has inherited an ethnic federal model that reinforces political, geographic, and ethnic differences. This is a recipe for polarization and instability. Indeed, Ethiopia has suffered from the growth of ethnic militias and a spike in ethnically based violence in recent years—resulting in an estimated 1.5 million people displaced. Encouraging power sharing with local governments, while strengthening ties to the center as well as reinforcing values of national identity and unity, therefore, are all part of the balancing act Ethiopia must seek to achieve. Failing this, Ethiopia’s viability as a unified state is at stake—a risk painfully illustrated by the violence in Tigray.

“Democracy-building is more than a single event but will require creating a democratic culture, a years-long effort.”

Another easily overlooked challenge with the move toward democracy is the steep learning curve rival candidates and parties face to compete within a civil framework. Democratic elections are intended as a forum for the competition of visions and ideas. This requires restraint and avoiding actions or rhetoric that can incite supporters to violence. Moreover, democratic elections are not existential battles. The power of winners is constrained by institutional checks and balances. Losers, likewise, live to fight another day, retaining the right to continue advancing their views, attracting supporters, and holding the government accountable. Reinforcing such themes will be a priority for civic education efforts, before and after the election.

This election cycle also faces the uncertainty of a highly fragmented party system. There are over 100 political parties competing in Ethiopia’s parliamentary system, many for the first time. Even Abiy’s ruling Prosperity Party has never competed in a national election before. This portends an unpredictable outcome and one that may involve the negotiation of some form of governing coalition, underscoring the value of maintaining civic and cooperative relations between parties. Given the novelty and uncertainty, the electoral environment in Ethiopia can be expected to remain fluid right up to and following the elections. While these historic polls offer unprecedented opportunities to broaden the scope of citizen participation, unless managed in a transparent and responsible manner, this unpredictability poses another point of instability for Ethiopia.

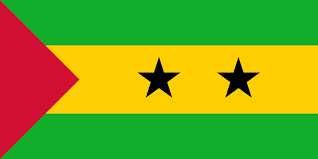

São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe

Presidential Election, July 18

President Evaristo Carvalho is seeking his second 5-year term in presidential elections in July. Carvalho was previously prime minister, president of the national assembly, and minister of defense. São Tomé and Príncipe enjoys a competitive multiparty democracy and a history of peaceful transfer of power between parties. The 2021 elections are expected to be freely contested and transparent.

President Evaristo Carvalho. (Photo: Agência Brasil Fotografias)

The president fills the role of head of state. Power is shared with a prime minister, who forms a government at the request of the president based on strength of parties following legislative elections. The current prime minister, Jorge Bom Jesus, came into office in 2019 and belongs to a rival party to that of the president. In 2019, tensions emerged between the president and prime minister regarding authority to appoint the governor of the Central Bank but were resolved.

Former prime minister Patrice Trovoada may contest the presidency, though he is currently in voluntary exile in Portugal fearing indictment on corruption charges from his time in office. Trovoada’s father was a popular president in São Tomé and Príncipe, and many support him. The country’s courts may rule him ineligible, however, if he does not live in São Tomé and Príncipe.

São Tomé and Príncipe’s relative political stability has enabled its 215,000 citizens to enjoy steady economic growth over the years, and the island country is now considered lower-middle income. Continued strengthening of its government oversight capability is a priority, however, to control corruption and continue its upward climb. This may be especially important with the potential for increased revenues generated from oil reserves in the Gulf of Guinea.

Zambia

Zambia

Presidential and Legislative Elections, August 12

Zambia’s presidential election is headlined by President Edgar Lungu’s attempt to secure a second full term in office. Lungu’s presidency has been marked by growing authoritarianism and the use of the ruling Patriotic Front’s youth militias, intelligence services, police, and military loyalists to intimidate his political rivals. He has also had opposition party members arrested on spurious charges, politicized the judiciary, restricted civil society, and closed independent media outlets that were critical of his government.

“As the world’s largest consumer of copper, China has invested heavily in Zambia copper mines.”

Lungu’s government has also been characterized by growing fiscal recklessness and concerns that Zambia is moving in the direction of its perennially unstable neighbor, Zimbabwe. Zambia’s external debt is estimated at $12 billion, and government debt as a share of GDP has risen from 20 to 120 percent under Lungu. Roughly a third of this is owed to China. Chinese-affiliated companies, likewise, have implemented over 80 percent of Zambia’s construction projects. As the world’s largest consumer of copper, China has invested heavily in Zambia copper mines. As Zambia seeks to restructure its debt it may be forced to place some of these mining assets into collateral.

In August 2020, Lungu replaced the respected governor of the Central Bank, Denny Kalyalya, with a political ally, Christopher Mvunga. This has raised concerns the Central Bank will print money in the runup to the elections. In November 2020, Zambia defaulted on a $42-million interest payment on its debt, making it the first African country to do so during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, Zambia’s GDP contracted by 5 percent, inflation grew by 15 percent, and the value of the kwacha fell by 30 percent, squeezing Zambians’ incomes. The government is now in negotiations with the IMF for an emergency loan.

The 2021 election is a repeat contest between Lungu and Hakainde Hichilema, leader of the United Party for National Development (UPND) and a commercial cattle rancher. Lungu took office in 2015 following the death in office of President Michael Sata. Lungu edged out Hichilema in the 2016 elections, which were marred by incidents of violence, voter intimidation, and unbalanced media reporting. In 2017, Lungu had Hichilema imprisoned on treason charges, which were widely viewed as bogus. While in prison, Hichilema was tortured and denied basic necessities. He was released after 4 months following a high-profile international advocacy campaign.

“While Lungu is viewed as having politicized state institutions, civil society and opposition networks remain resilient.”

While Lungu is viewed as having politicized state institutions, civil society and opposition networks remain resilient and Zambian society retains a strong commitment to the adherence of rule of law. Attempts to pass a new constitution through parliament—the so-called “Bill 10,” which would have further strengthened executive authority—were defeated in October 2020, despite the Patriotic Front’s majority. Zambian youth have innovatively organized virtual protests, including against government corruption. In June 2020, youth organizers frustrated police efforts to shut down planned street protests by instead livestreaming the event from their homes. More than a half million viewers watched the protests online.

Given the fraught history since 2015 and the stakes for Zambia’s democracy pending the outcome, emotions are likely to be high when Zambians go to vote in August. The space Hichilema has to campaign and the transparency and oversight of the vote counting will be key to watch.

Somalia

Somalia

Presidential Election, October (postponed)

Somalia’s presidential elections were originally planned for December 2020 but were pushed back, first to February and then to October, for logistical reasons and disputes regarding the oversight process. No precise date has yet been set due to a dispute over the voting structure. The Federal Government, led by President Mohamed Abdullah Mohamed (commonly known as Farmajo), and the five Federal Member States (FMS) agreed in September 2020 to jointly appoint an Electoral Commission and Dispute Resolution Committee. Ongoing disagreements on these selections may result in further delays. Consequently, just reaching an understanding on an equitable system may be as impactful as the results of Somalia’s 2021 elections.

Under Somalia’s current indirect electoral system, each of the country’s 275 parliamentarians will be elected by 101 delegates nominated by clan elders. These members of parliament, as well as 54 senators elected by state assemblies, will then select the president. This system of indirect election has been widely criticized as subject to delegate vote buying with seats going for up to $1 million each. The system is also seen as vulnerable to al-Shabaab’s influence on selecting delegates via financial incentives or through the sympathies of some clan leaders. The process has been a target of reformers who have pushed to have the president elected through universal suffrage, promoted as “one person, one vote.”

A meeting between Somali Federal Government and Federal Member States in 2017. (Photo: Puntland Presidency Press Office)

Farmajo is running for a second four-year term, and the difficulty of agreeing on a process highlights the low levels of trust the FMS have that the Farmajo government is committed to a free and fair process. The disagreement has forged greater cooperation of leading opposition parties under the Forum of National Parties. Among the leading opposition candidates are former presidents Sheikh Sharif Ahmed (2009-2012) and Hassan Sheikh Mohamud (2012-2016), as well as Ali Khaire, who was a former prime minister under Farmajo until he was relieved of his duties in July 2020, reportedly for his cooperative approach to the FMS.

The negotiations surrounding the electoral process reflect a deeper debate over the nature of the Somali state. Farmajo envisions a strong central state, while most of the FMS favor a decentralized system of power-sharing in line with the non-hierarchical, clan-based nature of Somali society. Key to the success of any agreement will be overcoming Somalia’s winner-take-all political culture that fosters a posture of domineering leaders at the expense of a coalition-building approach based on power-sharing.

The legitimacy of Somalia’s electoral process is closely tied to its prospects for stability. A process deemed fair and valid by the FMS and the public more generally will facilitate more cohesion, reducing the risk of internal conflict. It will also create a stronger base from which to address the regions’ varying claims of autonomy. A more legitimate and accountable political structure can also contribute to a more effective security force by strengthening the commitment to the federal cause.

Security remains the overarching tableau for Somalia’s 2021 elections. Al Shabaab was linked to an estimated 1,742 violent events and 2,369 reported fatalities in 2020, making it the most active and, arguably, most entrenched militant Islamist group in Africa. In addition to the possible disruptions to voting, al Shabaab remains in control over large swathes of the countryside.

“The elections reflect the challenge of fusing local clan and regional interests for autonomy within a larger national vision and policy framework.”

Somalia’s electoral process must also navigate the growing competition for influence by Gulf actors. Qatar and Turkey have been strong supporters of Farmajo and the federal government, while the UAE has backed the FMS. This regional competition for influence in Somalia (and with it, greater leverage over Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden networks of ports and trade) further elevates the pressure on Somalia’s already fractious political system. Growing tensions between the federal government and Kenya over border demarcations—and potential oil reserves—in the Indian Ocean, as well as security measures along the bordering lower Jubaaland, add to the mix of regional factors that have stakes in the outcome of the 2021 elections.

Somalia’s electoral process therefore must be understood within its larger interlocking state-building context. The elections reflect the challenge of fusing local clan and regional interests for autonomy within a larger national vision and policy framework. They also reflect Somalia’s geographic importance in the Horn of Africa and as an epicenter for violent extremism in East Africa. The elections and resulting leadership, therefore, have far-reaching security implications for Somalia and the broader region.

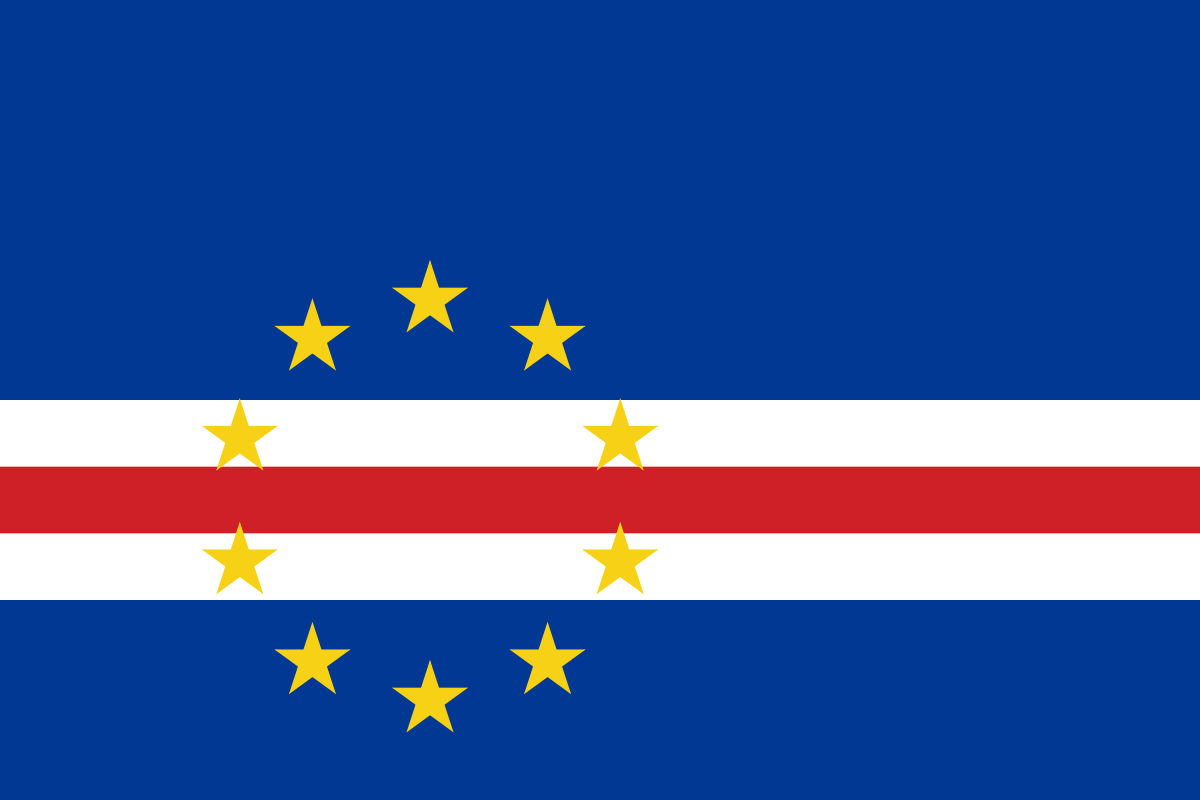

Cabo Verde

Cabo Verde

Legislative Election, April 18

Presidential Election, October 17

President Jorge Carlos Fonseca is stepping down in 2021 following the conclusion of his second and constitutionally limited five-year term. This is consistent with a 20-year tradition of upholding term limits in this Atlantic Ocean island nation of 500,000 people. The country also has a history of transparent, competitive elections and an alternation of power. Two main parties compete for power in the country: Fonseca’s Movement for Democracy and the African Party for the Independence of Cabo Verde.

Cabo Verde’s political system comprises an elected president and an appointed prime minister based on the results of legislative elections. Legislative elections occur 6 months prior to presidential polls. In 2019, the National Assembly adopted a Gender Parity Law, which introduced a quota requiring that 40 percent of the candidate lists at the national and local levels are women. The 2021 elections, therefore, will be the first time this quota will be implemented.

Cabo Verde’s record for good governance and political stability has translated into sustained economic growth and a steady decline in poverty. Through a strategy of inclusive growth and investments in human capital, the country has transformed itself into a middle-income economy.

The Gambia

The Gambia

Presidential Election, December 4

While 2021 only marks the end of Gambian President Adama Barrow’s first term, adherence to term limits is already overshadowing other considerations leading into this election.

Barrow came into office in 2016 after defeating longtime tyrant Yahya Jammeh in an election few expected would be fairly counted. Barrow promised that he would be a transitional leader and would only serve three years. Moreover, he established a commission to propose changes to the Constitution that would solidify a return to democracy in this small West African enclave.

President Adama Barrow. (Photo: European Council President)

When Barrow’s 3-year benchmark arrived, however, he declined to step down, triggering a sense of betrayal among his supporters. Similarly, the proposed constitutional revisions, considered by independent experts as a set of progressive reforms, were rejected by the Barrow-dominated parliament because they included a retroactive two-term limit for the president. Currently, the Gambian Constitution does not stipulate any term limits.

Barrow’s reversal has been a particularly bitter pill for his supporters since he represented a coalition of seven reformist parties when he won in 2016. Moreover, Gambians endured 22 years of brutal, and capricious repression under Jammeh. The physical and emotional pain caused by these human rights abuses remain fresh. Instituting constraints on the executive, therefore, is seen by many Gambians as an imperative lest the country fall into another prolonged era of impunity without the means of removing their leader.

Gambia’s 2021 election, thus, has taken on greater significance. It will be a test of reformers’ ability to mobilize support against an executive resistant to constraints. The extent to which Barrow will resort to force in deploying security actors for his political ends—and the degree to which Gambian security forces will allow themselves to be politicized following the public reproach of their role in enabling the Jammeh regime—will be important to watch.

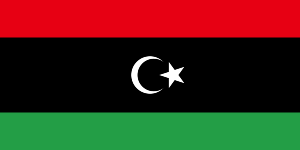

Libya

Libya

Presidential and Parliamentary Elections, December 24

In November 2020, Libyan politicians convened by the UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) to sketch out a plan to reunify the country agreed that Libya would have elections on December 24, 2021—the 70th anniversary of Libyan independence in 1951.

The aim is to establish an interim government joining the United Nations–recognized Government of National Accord (GNA), led by Fayez al Sarraj, which controls Tripoli and the west of the country, with the loose alliance comprising the Libyan National Army (LNA) militia and its leader, former general Khalifa Haftar, who remains the dominant force in the east.

“While the two sides have agreed to a ceasefire, they do not share a common vision for the future of Libya or even what a unified government should look like.”

The date seems overly ambitious since, while the two sides have agreed to a ceasefire, they do not share a common vision for the future of Libya or even what a unified government should look like. Other fundamental obstacles must be addressed as well before elections become a realistic possibility. Prime among these is the departure of foreign fighters that have been aiding each side, most notably Turkey, the primary benefactor of the GNA, and Russia and its Wagner mercenaries in support of the LNA. These fighters represent a broader mix of foreign interests, including Qatar, United Arab Emirates, and Egypt. In addition to jostling for influence over Libya and its strategic location in the southern Mediterranean, these actors are vying to maintain access to Libya’s on- and offshore oil reserves. Given these interests, it can be expected that the primary focus these external actors would have in elections is ensuring they can control the result.

It also remains uncertain that Haftar is interested in seeing a democratic outcome. His rebellion was launched, with the backing of his external supporters, to undermine the UN-backed government and seize power with the aim of establishing himself as a new strongman in Libya. Despite being forced to the negotiating table following his retreat from Tripoli, there is little reason to conclude that Haftar’s ambitions have changed.

In short, elections are not a substitute for reconciliation and peacebuilding. Without a commitment to a democratic system and lacking the checks and balances inherent in such a system, elections become just another polarizing competition by which rival forces attempt to gain power and an illusion of legitimacy.

Joseph Siegle is Research Director and Candace Cook is Research Assistant at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

More on: Democratization Benin Cape Verde Djibouti Ethiopia Gambia Libya Niger Republic of the Congo São Tomé & Principe Somalia Uganda Zambia