- Part 1: Identity

- Part 2: Faultlines

- Part 3: Extremism

- Part 4: Boko Haram

- Part 5: Strategies for combating extremism

- Part 6: Military professionalism

- Part 7: Maritime security

- Part 8: Governance

Extremist interpretations of Islam by marginalized communities in Nigeria have strong resonance as an avenue to address perceived injustices and economic inequalities. The dangers of extremism are especially pronounced in the Muslim-majority North which is substantially underdeveloped relative to other parts of the country. The economic disparities alone are stark: seventy two percent of northerners live in poverty, compared to 27 percent of southerners. The lack of confidence in government institutions combines with these realities to make communities across the North particularly susceptible to extremist messaging.

This state of affairs has caused intense resentment of the political status quo and fueled extremist and rejectionist thinking that Boko Haram has tapped into effectively to recruit new members and build its power. The movement’s extremist narratives invoke real and perceived grievances, often linking the North’s plight to corruption in the “Christian government” and accusing the northern Muslim leadership of colluding with it. The narratives also portray the corruption of Nigerian society as a function of Western influences, which are blamed for the North’s deprivation.

Boko Haram contends that the solution to Nigeria’s problems lie in the strict adherence to Islamic Law. In the early years after its founding in 2002 the movement was largely nonviolent. This changed in 2009 following a series of deadly clashes between its followers and security forces leading to over 800 deaths and the killing of its founder, Mohammed Yusuf. After going underground the group re-emerged in 2010. Its current leader, Abubakar Shekau, far more radical than Yusuf, has turned Boko Haram into one of the most brutal terrorist organizations in Africa, aligning it with the Islamic State, also known as ISIS.

The clashes in 2009 were not only a key turning point but also had historical precedents. In 1982, followers of another radical and charismatic Muslim cleric, Mohammed Marwa (known as Maitatsine, meaning “the one who damns”) clashed with authorities leaving 4,000 people dead in the northern city of Kano, including Maitatsine. However, this Muslim cleric’s movement, like Yusuf’s, lived on. His followers rose up again towards the end of that year, leading to 3,300 dead in long-running clashes with security forces and again in 1984 in Gongola, in the North, resulting in 1,000 deaths.

Why Are the Historical and Contemporary Roots of Boko Haram Relevant Today?

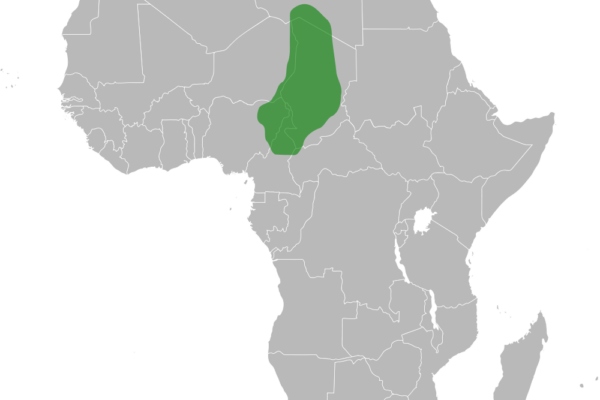

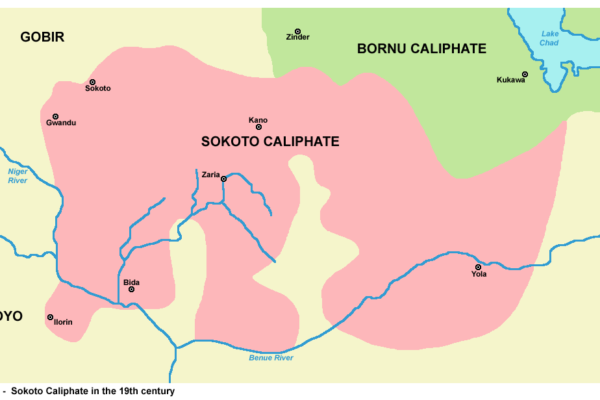

Northern Nigeria has a long history of Islamic government dating back to the Sayfawa Dynasty, which ruled the Kanem Bornu Empire from 1086 to 1846. Islamic governments were also established by the Borno Caliphate (1380–1893), and the Sokoto Caliphate (1804–1903). The three empires extended over most of northern and northeastern Nigeria, modern-day Burkina Faso and Cameroon, Niger, western Sudan and southern Libya. Most of Boko Haram’s recruits come from the Kanuri community, which ruled the Kanem Bornu Empire at its peak. The Kanuri language was also the official language of the more recent Borno Caliphate. The Kanuri remain highly influential and have produced several national level political leaders in modern Nigeria.

Presently this community of about 10 million, which still inhabits the lands of this former Caliphate and mostly traces its origins to Kanem Bornu, feels politically and economically disenfranchised. Many of the Kanuri view these Caliphates as a source of pride and an alternative governing framework from the current secular state, which is perceived as corrupt and incapable of serving the needs of the northern populations. Boko Haram has exploited this effectively. A key narrative in its propaganda emphasizes how much better off the Kanuri were under Caliphate rule. Boko Haram’s declared Caliphate in 2014 was an attempt to tap this sentiment – but with Takfiri ideology replacing the region’s Sufi traditions, which Boko Haram considers un-Islamic. Takfiri practice permits declaring other Muslims non–believers and targeting them for death, explaining the killing of hundreds of Muslims by Boko Haram.

This differentiation reflects a key problem underlying the spread of extremism in Nigeria. Many Muslim communities have turned to religious institutions for redress to the growing marginalization they feel. However, over recent decades, the identity of what it means to be Muslim in Nigeria has shifted. Today, militant interpretations of Islam are much more prevalent. And the history of Caliphate rule has provided a powerful reference point to advance this view. All of this creates an enabling environment for extremist ideologies to thrive.

In short, the underlying ideological appeal of violent, Islamist-based insurgencies in parts of northern Nigeria predates Boko Haram. Absent a comprehensive solution to the region’s grievances, extremist ideologies will live on even after the group is defeated militarily.

The next issue in this series will focus on the emergence of Boko Haram.

Further Reading

- Ali Mazrui, “Nigeria: From the Sharia Movement to Boko Haram,” Al Arabiya News, June 19, 2012.

- Femi Owolade, “Boko Haram: How a Militant Group Emerged in Nigeria,” Gatestone Institute, March 27, 2014.

- Freedom Onuoha, “Why Do Youth Join Boko Haram?” [PDF], United States Institute of Peace, June, 2014.

- Paul E Lovejoy, “Revolutionary Madhism and Resistance to Colonial Rule in the Sokoto Caliphate 1905–06” [PDF], Journal of African History, Vol 31, No 2 (London: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- Paul Chinazo Onwuegbuchulam, et al, “The Peacebuilding Potential of Islam: A Response to Boko Haram” [PDF], Conflict Trends, Issue 4 (Durban, South Africa: Africa Center for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes [ACCORD], 2014).

Africa Center Experts

- Benjamin Nickels, Associate Professor and Academic Chair, Transnational Threats and Counterterrorism

- Dorina Bekoe, Professor for Conflict Prevention, Mitigation, and Resolution

- Raymond Gilpin, Academic Dean

[Photo credits: SabrinaDan Photo; ArnoldPlaton; Panonian]

More on: Boko Haram Extremism Nigeria