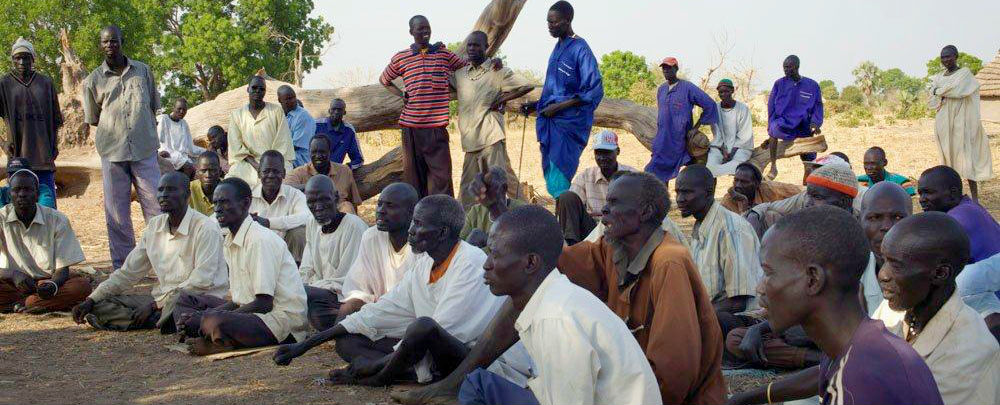

A traditional court in Warrap, South Sudan. (Photo: UNDP South Sudan/Brian Sokol)

Rule of Law in a Weak State

South Sudan’s descent into civil war in 2013, 2 years after independence, has devastated families, communities, and institutions—including judicial institutions. Already fragile following decades of war against Khartoum, state institutions had yet to penetrate throughout the territory, and many were still in the process of formation. Areas that lay beyond the reach of the state were nevertheless not ungoverned. Traditional chiefs and the rich tapestry of tribal norms and rules they applied to resolve disputes have played an invaluable role in holding communities together, much as they had during the decades of North-South fighting in the Sudanese Civil War, despite the multiple challenges they faced.

The new state of South Sudan has struggled with the militarization of private and public life, impunity, and personalized rule. As a consequence, constitutionalism and the rule of law—twin pillars of a state governed by law—have suffered. How, then, can the rule of law help establish stability in South Sudan? In particular, what role does the judiciary, including customary courts that constitute the lower rungs of the formal justice system, contribute to this enterprise?

Of Gun Culture and Absence of Rule of Law

Commentators have lamented the larger-than-normal role of the military in an ostensibly democratic, civilian-governed South Sudan. This state of affairs characterizes the low level of rule of law that persists in South Sudan. Rule of law connotes a state in which all, without exception, are subject to the law, the law and other institutions are allowed to function, and conflicts are mediated in terms of established rules and procedure. South Sudan has had a rule of law problem since its birth. This has been characterized by personalization of power, weak institutions including the judiciary which is subservient to the executive, a culture of violence, a lack of trust in institutions, and a pervasive military influence on public life, including on the administration of justice and resolution of disputes.

In its seminal 2013 report on the South Sudanese judiciary, the International Commission of Jurists decried the apparent weakness of the rule of law in South Sudan. It illustrated this finding with the case of an SPLA general who, faced with a lawsuit at the High Court in Juba, “paid the judge a visit” in the company of armed men and demanded to know when the judgment would be ready. While this constitutes an extreme case of intimidation of a judicial officer, it is symptomatic of other actions that compromise the independence of the judiciary. Equally, the capacity limitations of the formal judiciary—insufficient number of judges, limited number of courts over a vast territory, and poor working conditions for judicial officers—restrict the reach of legal institutions in the new state.

“Records suggest that an overwhelming number of cases that reach the courts … are decided by the underrated yet critical customary courts staffed by chiefs.”

The jurisdiction of customary courts, established under the Local Government Act of 2009, are limited in law to “customary disputes.” In practice, however, they hear and determine a wide range of cases that include theft, assault, rape, and homicide primarily because the customary courts are often “the only game in town” or litigants prefer them to formal statutory courts. Records suggest that an overwhelming number of cases that reach the courts—between 55 and 90 percent—are decided by the underrated yet critical customary courts staffed by chiefs. These courts, thus, fill a major gap in the provision of arbitral services left by formal justice, and are critical to security in rural areas and towns in South Sudan.

The Challenges and Resilience of Customary Courts

In spite of the role customary courts play in the delivery of justice and provision of security for citizens, this vital institution has faced strains due to the extended periods of war. This has included intimidation by the military that controlled liberated areas as well as the weakening of the authority of community leaders in the eyes of returning exiles whose views of tradition have been transformed by their lived experiences.

Customary courts in South Sudan are also constrained by being placed within the local government bureaucracy, which is widely recognized as ineffective and provides little support. Chiefs sometimes find it difficult to enforce their decisions and have, on occasion, been threatened with physical violence.1 Traditional leaders are also hamstrung in terms of larger conflicts between communities relating to access to pastures and water.

The proliferation of arms within the general population in South Sudan adds another layer of difficulty.2 In the absence of a reliable police presence in rural areas, customary courts headed by chiefs must at times rely on the SPLA to step into law-and-order roles to provide security and to enforce customary court decisions. Too often, however, the SPLA does not fill this role but instead acts with impunity, leaving citizens without recourse when they suffer violations. This undermines respect for the law, further complicating the work of chiefs and compounding the insecurity prevailing in rural areas.

While customary courts remain inadequate in many ways, in their absence, lawlessness would reign in large swaths of the territory. In fact, the critical role that traditional institutions play in the delivery of arbitral services during the current conflict has been recognized by the United Nations, which has set up elected “conflict resolution committees” in camps for internally displaced people.

“The customary courts have made important contributions to initiatives strengthening stability in South Sudan.”

Despite these challenges, the customary courts have made important contributions to initiatives strengthening stability in South Sudan. For example, during the last years of the civil war with Khartoum, the convening of a peace conference by community leaders at Wunliet between communities of the western bank of the Nile and their eastern bank counterparts—with the participation of armed actors and facilitation of the Council of Churches—pacified the feuding communities. It simultaneously united southern antagonists, thereby accelerating the peace process between the Khartoum regime and southern Sudan. Moreover, violence that engulfed Jonglei State in 2012 was quelled through a mix of co-option (the “Big Tent” policy) and the convening of a Wunliet-like peace process involving several communities. As preference for traditional forums by large sections of the population is, in part, due to the reverence with which elders and customs are still viewed, empowering them would reap dividends for the rule of law at the national level as well.

State Building and Rule of Law Interventions

Other than training for the small number of judges, magistrates, and prosecutors who were in place during the post-Comprehensive Peace Agreement period, the justice sector suffers from an acute shortage of judicial officers and prosecutors. Moreover, the first major hire of new judges in 2013 came too close to the start of this civil war and has not significantly improved service delivery. The justice sector also lacks infrastructure, with the few facilities that exist concentrated in Juba.

In the post-independence era, support directed at customary courts took the form of training by the United Nations Mission in South Sudan and other partners. Anecdotal evidence suggests that these interventions may not have had a discernible impact due to a multitude of structural factors including low levels of literacy, customary practices that may discriminate against women and youth, heterogeneity in terms of customary norms practiced by different communities in a diverse South Sudan, and chronic insecurity.

The United Nations Development Programme’s effort to document and harmonize customary laws has proceeded at a slow pace, is of narrow scope, and was interrupted by the 2013 conflict.3 The link and referral of cases between customary courts and the limited number of magistrate courts (in each county) that should exercise a supervisory role over the former is problematic. Circuit courts (High Court) introduced on a trial basis by the Chief Justice in two regions ameliorated the delivery of judicial services but were not funded adequately.

The inadequate support for customary courts mirrors the neglect of local and state governments in relation to national government institutions. This has had multiple effects, including increasing the potency of local conflicts, missed opportunities to build a culture of the rule of law from the grassroots, and leaving the periphery mostly ungoverned by law. This has also entrenched the use of force and insecurity as citizens resort to violence to “resolve” their disputes.

Recommendations

The rule of law is integral to the future stability of South Sudan. While the rule of law will be shaped by the broader political context in South Sudan, spreading the reach of informal courts into the country’s ungoverned spaces will be a vital component of any stability scenario. Priorities in this regard include the following.

Expand access to a month-long basic legal training for 1,500 paralegals to advise and guide the customary court chiefs on legal matters. In addition to strengthening the legal grounding of these courts, expanding the use of paralegals would create more opportunities for the participation of women and youth, making them more representative of the communities that they serve.

Develop a national framework (harmonization law) based on the constitution, human rights, and criminal laws. This would create uniformity in terms of how customary courts operate and provide opportunities for the sharing of experiences among customary law panels from different parts of the country.

The national framework must delink customary courts from the underfunded third tier of government—local government—and bring them within the fold of the national judiciary. This would respond to the marginalization of customary courts, affirm their critical role in the delivery of justice and security for citizens, enhance oversight over them by judges and magistrates, and build their capacity by providing resources, including token remuneration for adjudicators.

As part of a broader judicial reform effort, customary courts must be strengthened with greater support from local police who can enforce compliance with decisions. This will require recruiting, training, and deploying more police to provide security to customary law panels and to facilitate the implementation of their decisions.

Improve coordination and referral procedures between formal courts and customary courts. This calls for the expansion of registries in formal courts to make provision for filing, documentation, and transfer of cases between courts upon a review of the facts by a magistrate, judge, or registrar. The registration of community leaders involved with customary courts would facilitate regulation, training, remuneration, record-keeping, and sanctioning as required.

Notes

- ⇑ David K. Deng, “Challenge of Accountability: An Assessment of Dispute Resolution Processes in Rural South Sudan” (Juba: South Sudan Law Society, 2012), 32-33.

- ⇑ Ibid.

- ⇑ Tiernan Mennen, “Study on the Harmonization of Customary Laws and the National Legal System in South Sudan” (Juba: United Nations Development Programme, 2016).

More on: Stabilization of Fragile States Rule of Law South Sudan