Also available in: Français | Português

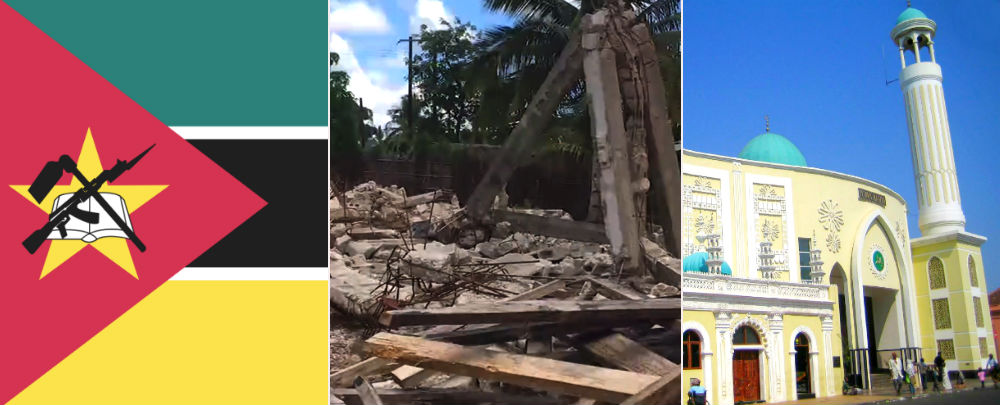

The emergence of a new militant Islamist group in northern Mozambique raises a host of concerns over the influence of international jihadist ideology, social and economic marginalization of local Muslim communities, and a heavy-handed security response.

Photos: Nightstallion, VOA, James et Alex BonTempo.

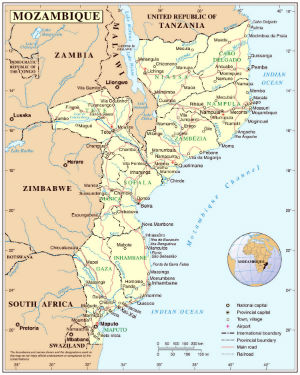

News of an October 5, 2017, attack by a militant Islamist group on several police stations, government officials, and residents in the town of Mocímboa da Praia in Cabo Delgado Province, Mozambique, caught observers of international jihadism by surprise. The existence of the group was not a surprise to members of the Province’s Islamic Council, however. Council members said that for several years they had been warning authorities about the group and the threat to peace posed by its extremist ideology. Despite the warnings, it appears that the national police only began to take action in May 2017, arresting members of what police called Mozambique’s al Shabaab in Quissanga and Macomia Districts. By mid-March 2018, the police said that they had arrested 470 individuals and prosecuted 370, of which 314 were Mozambican, 52 Tanzanian, 1 Somali, and 3 Ugandan.

The October 2017 assault on the police stations suggests that the attackers had specific grievances against local security forces. Local residents said that after the attack, many local Muslim youth disappeared from the region. Rumors explaining the disappearances range from extrajudicial executions by Mozambican security forces to suggestions that some youth fled into nearby Tanzania to avoid possible targeting.

The October 2017 assault on the police stations suggests that the attackers had specific grievances against local security forces. Local residents said that after the attack, many local Muslim youth disappeared from the region. Rumors explaining the disappearances range from extrajudicial executions by Mozambican security forces to suggestions that some youth fled into nearby Tanzania to avoid possible targeting.

In late December 2017, government forces carried out a helicopter raid and a bombardment from naval vessels on the village of Mitumbate in Mocímboa de Praia District, which was believed to be the group’s stronghold. Government forces reportedly killed 50 people including women and children and detained some 200 others. Local health authorities told a Mozambican newspaper that their hospital facilities were overwhelmed with wounded seeking treatment.

Despite assurances by the Mozambique’s national police that it had restored peace in Mocímboa da Praia, there have been additional attacks in the Province attributed to the group. The violence has caused some multinational companies who are investing in the region to evacuate employees.

The group—known locally both as al Shabaab (the youth) and as Swahili Sunnah (the Swahili path)—appears to be attracting new recruits. On January 13, national police arrested 24 men traveling on a bus from the Nacala, Nampula Province, whom they suspected of traveling to join the group in neighboring Cabo Delgado Province.

Armed youth during the October 5, 2017 attack in Mocímboa da Praia. (Photo: VOA)

Leadership Ties to International Jihadism

The group’s leadership appears to be inspired by international jihadism, holding similar aims and goals, such as the establishment of an Islamic state following Sharia and the eschewing of the government’s secular education system. According to mainstream imams in Mocímboa da Praia and Montepuez districts, one of the leaders is a Gambian named Musa. The other, a Mozambican, goes by the name Nuro Adremane. The latter reportedly received a scholarship to train in Somalia, traveling by road through Tanzania and Kenya to reach Somalia, as did a number of other members of the group. The Gambian leader actively sought out recruits in Montepeuz District among segments of the population with grievances against both the security forces of an international mining company and the national police, suggesting that the Gambian was attempting to transform local grievances into a narrative of revenge.

The fundamentalist interpretations of Islam espoused by the militant group reinforce an ideology introduced in the region in recent years by youth who have received scholarships to study in Sudan, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf States. This is at odds with the Sufi-inspired Islam that has long been practiced in the region.

For the last several years, the group operated two mosques in Mocímboa da Praia where they taught their version of Islam. Children who have been studying at these and other fundamentalist mosques introduced in recent years, have reached the age of participation in militias. Government authorities closed down the two mosques after the police action started in May 2017.

According to Sheikh Bakar of the Islamic Council in Montepuez, the group’s leadership had been influenced by the Mombasa-based Kenyan radical imam, Sheikh Aboud Rogo Mohammed, who preached in Swahili and whose videos were distributed throughout the East Africa region. Sheikh Rogo had been placed on U.S. and United Nations sanctions lists for allegedly supporting Somalia’s al Shabaab militants. In 2012, unknown assailants assassinated Sheikh Rogo in Mombasa.

“Until recently, this region had been known for its exceptional tolerance and welcoming attitude toward visitors from around the world.”

The second moniker used for the group—Swahili Sunna—suggests a goal of establishing a Swahili state among the Swahili-speaking coastal populations. The reference appears to harken back to an earlier period when a series of Swahili city-states dotted the East African coast from southern Somalia to Mozambique. The main Zanzibar island known as Unguja became a center of Islamic scholarship in the East African region, reinforcing a Sufi-inspired Islam in East Africa known for its tolerance of indigenous customs. Over the centuries since 1498, Arab, Portuguese, Dutch, East Indian, and British traders vied for commercial dominance in this region.

The Omani royal family took control of Zanzibar in 1698, and around 1840, Oman moved its capital to Zanzibar. The Sultan of Zanzibar, who was a member of the Omani royal family, ruled a stretch of coastal land from Malindi in present-day Kenya into northern Mozambique, where Swahili functioned as the lingua franca. Zanzibar became a British protectorate in 1890 and the Swahili coastal communities became divided among Britain, Germany, and Portugal. Until recently, this region had been known for its exceptional tolerance and welcoming attitude toward visitors from around the world who would flock to the East African coast.

Mosque in Mocímboa da Praia destroyed after the October 5, 2017, attack. Photo: VOA.

Social and Economic Challenges in Cabo Delgado and the Push for Vengeance

Considerable social and economic stressors in Cabo Delgado Province may help to explain why the jihadist message of achieving justice through the establishment of an Islamic state found resonance among segments of the youth. Unemployed young men in the region have often found themselves in the position of not having the resources to pay bridewealth to secure a wife. As a result, they end up in a permanent state of seeking to become an adult, never having the wife and family that would make them adults in traditional culture. Such young men unable to attain adulthood can become easy recruits for armed militias.

Cabo Delgado Province has been the focus of considerable investments in infrastructure to support extraction of petroleum, natural gas, and the world’s largest pink sapphire and ruby deposits. However, locals often complain that employment in infrastructure development such as roads has gone to outsiders, mainly Zimbabweans, and that land is being expropriated without proper compensation.

In addition, there has been speculation that alleged human rights abuses by the UK-based Gemfields, including the expropriation of land from locals, reportedly fueled the taking up of arms by those joining the armed Islamist group operating in Mocímboa de Praia. In 2017, British law firm Leigh Day investigated reports of human rights abuses in Cabo Delgado at the request of the Roman Catholic Bishop of Pemba in Cabo Delgado. According to another report, the jihadist group has had success in recruiting youth in the Montepuez District, which is home to the gem mining operations.

“Locals often complain that employment in infrastructure development such as roads has gone to outsiders … and that land is being expropriated without proper compensation.”

Gemfields’ concession in Montepuez is believed to contain 40 percent of the world’s supply of rubies. According to a 2016 investigative report for 100Reporters, over a three-year period locals were forced off their land, armed robberies and violence soared, and a number of small-scale miners were beaten, shot, and even buried alive. The report found both company security forces and Mozambican police complicit in the abuses that peaked in 2014, and some of the private security guards were prosecuted for their crimes. According to Gemfields, however, neither its subsidiary, Montepuez Ruby Mining Limitada, nor its officers, staff, or contractors engage in violence toward or intimidation of the local community. In February 2018, Leigh Day filed a claim with the High Court of England and Wales against Gemfields on behalf of 29 individuals alleging human rights violations by state and private security guards protecting Gemfields’ Montepuez ruby mine.

The expropriation of land in other areas of the province for use by multinational companies has created consternation and social stress among the population. Some residents who were uprooted by the development plans complained that the legal process was rushed and compensation less than expected. Both farming and fishing communities were displaced in the process. The expropriated land will be used in separate projects undertaken by the U.S.-based Anadarko Petroleum Corporation and the Canadian petroleum company Wentworth.

At a time when local residents felt marginalized economically, Mozambique’s Minister of Labor traveled to Cabo Delgado in February 2018 to lay the groundwork for receiving 2,000 foreign workers who would be working on the Anadarko project. Anadarko had received authorization from the Mozambican government to build an onshore liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant in Palma, one of the districts in Cabo Delgado the militant Islamist group has terrorized. Investments in Anadarko’s larger Offshore Area 1 project in the Rovuma Basin (of which the LNG plant in Cabo Delgado is a part) are expected to total $12 billion. The project will generate an estimated 5,000 jobs in the construction phase and 1,000 during production. Wentworth has an agreement with the Mozambican government for onshore exploration.

Finding a Way Forward

A growing cycle of grievance and revenge between militant Islamists and security forces is taking hold in Cabo Delgado province. With narratives of vengeance taking hold, it is challenging to unpack grievances to find a negotiable solution. The militants justify their actions from a position of moral superiority and with the rectitude of those who have been victimized and humiliated. Meanwhile state security forces also feel aggrieved and victimized. This creates a scenario in which the cycle will only escalate. Finding a common ground is no easy task. However, some steps that can be taken to help defuse the crisis in Cabo Delgado include the following:

- Train the national police, other state actors, and private sector security forces to carry out their responsibilities in ways consistent with international standards of human rights in conflict settings. This should be accompanied by providing the means for holding security forces accountable. Such actions are important not just on their own merit but also because the failure to uphold human rights standards has been recognized as one of the strongest drivers of militant recruitment on the continent.

- Offer an amnesty program for youth who have taken up arms, drawing from lessons learned in areas such as the Niger Delta region of Nigeria where local grievances against multinational petroleum companies led to sustained long term-violence by segments of the local population.

- As part of the amnesty program, offer rehabilitation with skills training and employment opportunities.

- Establish a Mozambican government commission with representatives from the faith community to examine the allegations of abuse by multinational mining interests, and offer compensation to the aggrieved if abuse is established.

- Establish a comprehensive stakeholder commission with strong representation from affected communities to examine the impact of large-scale external investments on the local economy and livelihoods. Such a commission could serve as a forum to consider grievances and solutions as a means of preventing the further escalation of conflict and making the communities feel whole.

- With the aim of enhancing long-term stability, the government and multinational corporations should make investments in community development—such as in health, agricultural and fishing assistance, and skills training—ensuring that the local population benefits significantly from new employment opportunities.

Greg Pirio and Robert Pittelli are the President and Associate of EC Associates, respectively. Yussuf Adam is an Associate Professor of Contemporary History at the University of Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo, Mozambique.

Africa Center Experts

- Benjamin Nickels, Associate Professor of Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency

- Wendy Williams, Adjunct Research Fellow

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “More Activity, Fewer Fatalities Linked to African Militant Islamist Groups in 2017,” Infographic, January 2018.

- Daisy Muibu and Benjamin Nickels, “Foreign Technology or Local Expertise? Al-Shabaab’s IED Capability,” CTC Sentinel, November 27, 2017.

- Abdisaid M. Ali, “Islamist Extremism in East Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 32, August 2016.

- Clement Mweyang Aapenguo, “Misinterpreting Ethnic Conflicts,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 4, April 2010.

More on: Mozambique