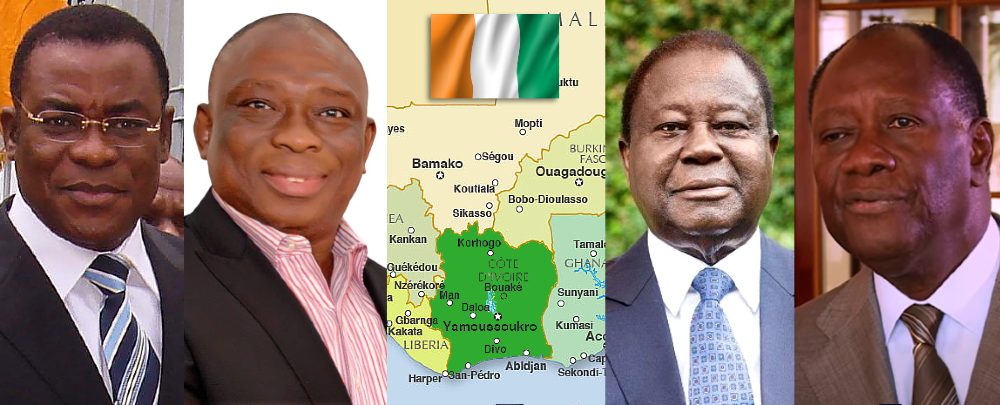

Côte d’Ivoire candidates (left to right) Pascal Affi N’Guessan, Kouadio Konan Bertin, Henri Konan Bédié, and Alassane Ouattara. (Images: Zenman, Juliengoujon75, HKBofficiel, video screen capture)

Ten years after a civil conflict that led to 3,000 deaths, tensions are again rising in Côte d’Ivoire. Although it has made progress in reunifying the country over the past decade, the October 31 election has brought to the surface long-simmering differences of identity and vision for the country. Adding to the combustible atmosphere, President Alassane Ouattara is running for a controversial third term. Following are some of the underlying issues shaping this important juncture in Côte d’Ivoire’s history.

1. Côte d’Ivoire Today vs. 10 Years Ago

Côte d’Ivoire has changed dramatically in the ten years since Alassane Ouattara assumed the presidency. In 2011, the economy was in tatters and the country was effectively split in two, each with its own army. A UN mission, UNOCI, and the French Licorne force helped to provide security. Since then, the Ouattara administration has overseen a period of unprecedented economic expansion, averaging 8 percent growth per year since 2011, restoring Côte d’Ivoire to its status as a regional economic powerhouse. Ouattara has also overseen the creation of a national health coverage mandate and improved access to electricity and education. His government has also worked to strengthen numerous national institutions, including the security sector.

“While the overall poverty rate has decreased … this has mostly benefited urban areas in the coastal south, exposing stark regional and ethnic divisions.”

Nonetheless, economic progress has been uneven, marked by continued inequality. According to the World Bank, while the overall poverty rate has decreased from 55 percent in 2011 to 39 percent in 2018, this has mostly benefited urban areas in the coastal south, exposing stark regional and ethnic divisions. Moreover, some infrastructure projects, such as road construction, have come with a cost to the urban poor. In Abidjan for instance, infrastructure construction projects required the relocation of nearly a fifth of the city’s population, most of them in informal settlements.

Trust in institutions also remains low. In a 2019 survey, Afrobarometer found that just 50 percent of respondents trusted the president, 45 percent the military, 44 percent the police, 43 percent the courts, and 37 percent the electoral commission. Trust in political parties was also weak, with 41 percent saying they trusted the ruling Rassemblement des Houphouëtistes pour la démocratie et la paix (RHDP), and 37 percent saying they trusted opposition parties.

Accountability remains limited, with abuses, including arbitrary detentions and killings, police mistreatment, and corruption often going unpunished.

2. Multiple Internal Fissures

Continued polarization between the mostly Muslim north and the largely Christian south continues to be at the heart of the rising tensions. Political power has historically been held by the urban, coastal south and the capital Abidjan. The up-country regions, in addition to being more marginalized, tend to host immigrants who come from throughout West Africa to work in Côte d’Ivoire’s world-leading cocoa sector.

Laurent Gbagbo in August 2007. (Photo: Wavemaster)

The concept of Ivoirité, adopted in 1994, required any office seeker to prove that both parents were Ivorian, effectively excluding many northern politicians, including Ouattara. Escalating tensions led to civil war in 1999-2003 and were at the center of the 2010-2011 electoral crisis when then President Laurent Gbagbo refused to step down after he was defeated at the polls. During the administrations of presidents Henri Konan Bédié and Gbagbo (1993-2011), many northerners were barred from seeking office. The perception that southerners were favored has been reversed since 2011 with a view that northerners are now advantaged. This perspective was sharpened by a suggestion early in the Ouattara administration, that northerners needed to benefit from a “catching up” (“rattrapage”) program, something Ouattara has denied promoting.

The Ouattara administration also chose to focus on economic growth rather than on healing the rifts caused by Ivoirité and the divisions of the civil war. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Commission dialogue, vérité et réconciliation) was formed in 2012 but never released a report. It was also criticized for not sufficiently engaging with civil society and citizens more generally. Subsequent calls for renewed dialogue have fallen flat.

Ouattara’s decision to pursue a third term is another factor in the rise in tensions. More than 78 percent of Ivorians favor a two-term limit for the presidency. When advocating for a new constitution in 2016, Ouattara had pledged not to run again. In fact, he moved to step down in March 2020 by designating his Prime Minister, Amadou Gon Coulibaly, as his party’s presidential candidate. But when Gon Coulibaly died suddenly in July, Ouattara was forced to reconsider. A Constitutional Council ruling that the adoption of the new Constitution had reset the term limit clock, opened the door for Ouattara. Many in the opposition, however, decried the move as unconstitutional. No doubt part of Outtara’s motivation is that the leading opposition candidates, former President Henri Konan Bédié and Pascal Affi N’Guessan, Gbagbo’s Prime Minister, are a throwback to the past exclusive governing system and a threat to the progress made over the past decade.

Protesters against a third term for President Ouattara.

Indicative of the heightened tensions, some violence has already occurred. At least 15 people have been killed in protests against a third term, and N’Guessan’s house was set on fire. With the opposition calling for civil disobedience, boycotts, and obstruction of the election, the risk of additional violence is high.

3. A Divided Security Sector

When Ouattara assumed office in 2011, there were effectively two armies in Côte d’Ivoire. The formal army supported Gbagbo, and the Forces nouvelles (FN), an alliance of northern groups, supported Ouattara. The Army was better equipped and trained while the FN, which was led by zone commanders (“comzones”), was made up of volunteers with little formal training.

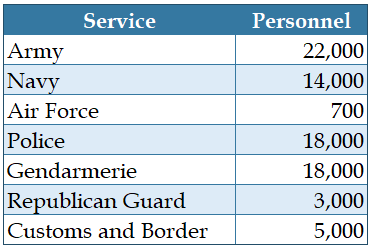

On assuming office, Ouattara launched a wide-ranging security sector reform (SSR) program that aimed to integrate these two forces, decrease their bloated ranks, and improve their professionalism through the creation of several professional military education institutions. The disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration process saw 70,000 people give up their weapons and opt for a return to civilian life. Overall, however, the SSR process has seen mixed results with a view that too many comzones, despite their lack of training, have been promoted to high-level positions. Today, the security sector consists of the following:

Divisions within the domestic security forces also persist, with the police thought to be loyal to Ouattara and the gendarmerie to Gbagbo.

In 2017 and 2018, parts of the Army, many of them former rebel forces, mutinied, demanding salary arrears. Large parts of the security sector remain effectively divided between the north and south. The security sector, furthermore, continues to be dominated by the older generation, preventing younger officers from assuming leadership positions. As a result, the loyalties of various elements of the security sector remain unclear.

Impunity also remains a problem. Human rights groups have claimed that rival militias and armed youth groups associated with political parties continue to be active. During protests against a Ouattara third term in August 2020, Human Rights Watch reported that individuals who did not identify themselves as part of the police brandished knifes and machetes to beat and disperse protesters.

4. Weak Political Parties

“Since the death of President Houphouët Boigny in 1993, the same political figures and the same parties … have dominated the political scene.”

Until 1990, Côte d’Ivoire was a single-party state with only the Parti démocratique de Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI). This legacy and the continued personalization of Ivorian political parties have stunted their organizational development. Since the death of President Houphouët Boigny in 1993, the same political figures and the same parties, either drawn from the PDCI and its splinters, or from the opposition, have dominated the political scene.

Henri Konan Bédié, now 86, who succeeded Boigny, took over the mantle of leading the PDCI in 1993. Ouattara, 78, who had been Bédié’s Prime Minister but was forced into exile following the adoption of Ivoirité, created the Rassemblement des républicains (RDR). Eventually, the RDR morphed into the RHDP. Likewise, Gbagbo, 75, a longtime member of the opposition during Boigny’s tenure, created the Front populaire Ivoirien (FPI).

These personality-based parties continue to be weak because rather than representing an ideology, a set of policy priorities, or an approach to governance, they largely serve as platforms for their leaders. Their repeated alliances and splits, and their failure to allow their younger members to take up leadership positions, have inhibited their growth and renewal. This is a concern for a country whose median population is age 18.

Guillaume Soro

(Photo: Africa1979)

Indicative of this stagnation are the challenges many of the parties have had with succession internally. Kouadio Konan Bertin, 57, one of the four approved presidential candidates, had long served in the PDCI, calling Bédié his father. However, only by splitting from his party was he allowed to run. In Gbagbo’s FPI, N’Guessan was put forward as its candidate only because Gbagbo was awaiting trial at the International Criminal Court. Nonetheless, a split persists in the party between those who believe only Gbagbo can represent the FPI and those who accept his ineligibility and believe that the party requires new leadership.

The RHDP’s succession was derailed when Gon Coulibaly died in July. Gon Coulibaly was often described as Ouattara’s “dauphin,” the French term for the king’s heir, reflecting a personalized view of power and government. Other younger members of the RHDP, feeling they lacked opportunities within the party, have split away and formed their own parties. These include former Foreign Minister Marcel Amon Tanoh, former Vice President Daniel Kablan, and former Minister of Education Albert Toikeusse Mabri. Most prominently, Guillaume Soro resigned as president of the National Assembly in February 2019 to form his own party, the Generations and People in Solidarity (Générations et peuples solidaires).

5. Questions over the Independence of Electoral Institutions

The adoption of the 2016 Constitution led to the revamping of key electoral institutions, namely the Constitutional Council, the highest court in Côte d’Ivoire, and the Commission électorale indépendante (CEI). Each has an important role to play in organizing and certifying the vote.

The Constitutional Council certifies the eligibility of the candidates and then the validity of the vote itself. The opposition has called for the Council’s dissolution, citing a composition it views as biased in favor of the incumbent. The Council is composed of former presidents (though they must resign if they are running for office or cannot be seated if they’ve been stripped of their civic rights) and seven other members. The President appoints the president of the chamber and three others. The Presidents of the National Assembly and the Senate appoint two and one, respectively. Only the President of the Senate, Jeannot Ahoussou-Kouadio, is a member of an opposition party. While the members of the Constitutional Council must have relevant qualifications, the fact that they are named by the president or his partisans makes them suspect in the eyes of the opposition. When the opposition filed a suit with the Constitutional Council to stop the Ouattara candidacy, it was rejected.

“The opposition … views as suspect the fact that 40 out of 44 candidacies for president this year were rejected on what they say are technicalities.”

The opposition also views as suspect the fact that 40 out of 44 candidacies for president this year were rejected on what they say are technicalities. Most prominent were the rejections of Gbagbo and his former Prime Minister Guillaume Soro, both of whom had been stripped of their civic rights due to convictions in Ivorian courts. Gbagbo had been convicted for attacks against the Central Bank during the 2010-2011 electoral crisis and was facing charges with the International Criminal Court. Soro, meanwhile, was rejected due to a conviction for embezzlement. As a result, only Ouattara, Bédié, N’Guessan, 67, and Kouadio Konan Bertin, 57, a former congressman who split from Bédié’s party, have been allowed to run.

The CEI was restructured in 2019 after the AU Court for Human Rights called for its reform in a 2016 ruling. However, the opposition has refused to participate, even though opposition parties and civil society have seats designated for them.

6. Democratic Space

Since early 2019, the Ouattara administration has taken steps to limit the opposition and the ability of potential challengers to run for office.

Some opposition leaders have been arrested and detained. In January 2019, Alain Lobognon, a Soro ally in the National Assembly, was arrested and convicted to a suspended jail sentence for spreading “fake news” about government corruption. In September 2019, a Vice President of the PDCI, Jacques Mangoua, was arrested and sentenced to five years in prison after weapons were found at his house. Both of these cases were denounced as politically motivated.

Pulchérie Gbalet, who was arrested for organizing protests. (Photo: Edwige Kobly)

A new penal code adopted in June 2019 severely limits the right to protest since it bans public protests that are deemed to threaten public order. In August 2020, the government banned street protests, citing the COVID-19 pandemic health emergency. Subsequently, Pulchérie Gbalet, a member of the civil society group Alternative citoyenne ivorienne, was arrested for threatening public order for organizing a protest against Ouattara’s third term. Opposition leaders have called the ban, which was lifted on October 15 when the presidential campaign officially began, political.

Soro, 48, the former leader of the rebel FN, is considered an example of how the Ouattara administration has sought to sideline those it perceives as the most credible candidates. Despite his youth, Soro previously served as Gbagbo’s prime minister between 2007 and 2012 and President of the National Assembly between 2012 and 2019. But allegations of corruption—Soro was initially accused of embezzling public funds to build a private residence when he was Prime Minister in 2007 and later for plotting to threaten the safety of the state—have derailed his candidacy. Soro remains in exile in France, with a pending arrest warrant preventing his return to Côte d’Ivoire. The charge that he threatened the safety of the state, which was accompanied by the arrest of 17 of his partisans, including one of his brothers, is seen as politically motivated. In April 2020, Soro was tried in the corruption case in absentia, with his lawyers refusing to participate. A jury returned a guilty verdict in less than three hours. This prompted the AU Court for Human Rights to call for charges to be dropped and for his civic rights to be reinstated so that he could run.

Restrictions on the press have also grown in recent years. The adoption of a new penal code in 2019 criminalizes offenses toward the president, the publication of fake news, insults on the internet, and data that could be a detriment to public order. Since then, journalists have been detained, fined, and imprisoned for publishing stories on topics such as corruption and the spread of COVID-19.

Conclusion

Despite noteworthy economic progress and rebuilding from the conflict of a decade ago, Côte d’Ivoire faces serious internal strains. These reflect a combination of factors including competing visions of national identity, a fragmented security sector with divided loyalties, barriers preventing a next generation of political leaders to emerge, restrictions on independent media, and weak oversight institutions. Already some violence has occurred and there is potential for sustained unrest. Regardless of the outcome of the election, considerable work will be required to address these institutional challenges if Côte d’Ivoire is to avoid a return to instability and resume its upward economic trajectory.

Additional Resources

- Jessica Moody, “Familiar Faces and Threats: Côte d’Ivoire’s Contentious October Election,” in Polls in Peril? West Africa’s 2020 Elections, Centre for Democracy and Development, Vol. 6, No. 6, 2020.

- Francois Patuel, « Dégradation de l’espace civique avant les élections dans les pays francophones de l’Afrique de l’Ouest, Études de cas : Bénin, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinée, Niger et Togo, » CIVICUS, October 2020.

- Joseph Siegle and Candace Cook, “Circumvention of Term Limits Weakens Governance in Africa,” Infographic, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, September 14, 2020.

- Joseph Siegle and Candace Cook, “Assessing Africa’s 2020 Elections,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 28, 2020.

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Africa Security Brief, No. 6, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2014.

- Thierno Bah, “Addressing Côte d’Ivoire’s Deeper Crisis,” Africa Security Brief, No. 19, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 2012.

More on: Côte d'Ivoire Democratization