UN peacekeepers examining weapons during demobilization efforts in the DRC. (Photo: UN/Martine Perret)

The African Union’s (AU’s) roadmap to “Silencing the Guns” by 2020 (now extended to 2030) includes arms embargoes as a strategic pillar and calls for better national, regional, and international coordination to deny armed groups access to weapons, finance, and other means to make war. Arms embargoes have long been part of a toolbox of instruments to end some of Africa’s deadliest conflicts, including those in Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Liberia, Rwanda, Somalia, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, and Sudan, and between Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Besides weapons, arms embargoes have also sought to disrupt access to natural resources, like diamonds, as well as to impose travel bans and freeze assets, to increase the costs of noncompliance by those who benefit from war. Arms embargoes do not always work as intended, however. Third parties, both within the region and beyond, sometimes actively participate in violating arms embargoes, reducing their effectiveness. The United Nations (UN) has decried what it calls “blatant” and “extensive” violations of a UN arms embargo in Libya including by Russia and Turkey who have sold embargoed items, such as drones, transport aircraft, surface-to-air missiles, artillery pieces, and armored vehicles, to different factions involved in the fighting, even as a UN-brokered Government of National Unity prepares the country for elections.

The Central African Republic (CAR) faces a similar situation. It is struggling to implement a 2019 AU/UN-brokered agreement—the seventh in eight years—between 14 armed groups. Despite a 2013 UN arms embargo, weapons, military equipment, and money continue to flow to various groups, including a coalition of six militias formed in 2020 that controls about two-thirds of the country.

Arms embargoes, and sanctions more broadly, are the subject of much debate in Africa, not least because African countries have been the target of the lion’s share of these coercive measures since the UN’s 1963 embargo (expanded in 1977) against apartheid South Africa. Since then, embargoes in Africa have been used in many contexts. However, these embargoes are regularly flouted, undermining the continent’s commitment to “Silencing the Guns.”

A Vexing Problem

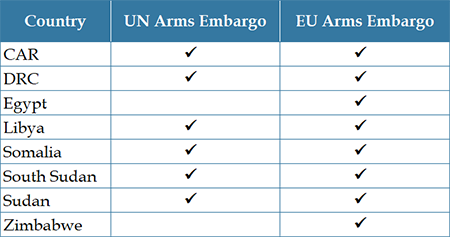

The UN currently has arms embargoes in six countries in Africa. The European Union (EU), which uses the UN list as a floor for its own more stringent standards, includes an additional two African countries for arms embargos.

UN sanctions are typically imposed under Chapter VII, Article 41 of the UN Charter. It obliges member states to enforce the sanctions and report on steps taken to do so. The willingness and capacity of individual countries to follow through, however, varies at times, imperiling the effectiveness of the sanctions. Since 1999, the UN Security Council has routinely created independent panels of four to six experts to monitor arms embargo violations and make recommendations to UN sanctions committees for further action. In cases where a UN peace operation is deployed, it is also often tasked with assisting in monitoring the sanctions.

Expert panel reports show that arms embargoes are both difficult to monitor and to enforce. In some cases, the embargoes were structurally inadequate. For example, the UN embargo in Sudan’s Darfur region was initially only applied to nonstate armed groups as a compromise because some UN Security Council members opposed a broader application that would also have targeted the Sudanese government. A year later, however, given that the government was arming and providing logistical support to the Janjaweed, even after signing a cease fire agreement, the arms embargo was extended to all belligerents in Darfur.

In the case of South Sudan, conflict actors were able to circumvent the arms embargos by stockpiling weaponry acquired in anticipation of their imposition, further highlighting the problems involved in designing sanctions and enforcing compliance.

“Shifting networks of conflict actors, interests, and power dynamics within each conflict are not always considered in the design of arms embargoes.”

In other cases, targeted actors have capitalized on the complexity of conflicts to devise evasive tactics. Militias in the DRC, for example, acquired weapons through arrangements involving third parties in exchange for minerals. This enabled them to conduct transactions entirely outside the formal banking system, making them completely unaffected by sanctions and further emboldened as a result. For example, on being informed that he was on a sanctions list, a Congolese militia leader remarked, “So even the UN now knows me? That means my group is becoming famous.”

On the other hand, the NDC-R, a government allied Congolese rebel group that once controlled the most territory in the Kivu provinces, collapsed in 2020 after its leader, Guidon Shimiray Mwissa, was listed by the UN for extensive human rights abuses. His deputy removed him from the leadership post citing Guidon’s position on the sanctions list as an impediment to integrating the group’s thousands of combatants into the Congolese armed forces.

Porous borders, weak or nonexistent state capacity, and corruption are also to blame. The June 2020 Report of the UN Group of Experts on the DRC found that militia leaders, to evade sanctions, had built a parallel trading system to such an extent that that the volume of smuggled gold in their areas of operation was several times the volume of legally traded gold.

The lack of state capacity extends to immigration and monitoring. For example, Congolese customs authorities lacked the equipment necessary to identify fraudulent travel documents and could not therefore interdict designated persons. In Liberia and Sierra Leone, arms traffickers used evasive routes such as rivers and dense forests to avoid border authorities and UN peacekeepers. However, many illicit arms shipments are simply flown into a target country given lax oversight.

Meanwhile, several UN panels have complained about the general lack of awareness among citizens and governments about how sanctions work and what they are meant to achieve. Bad actors can therefore go about their business unconcerned about sanctions with little risk that they will be identified and exposed.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres meeting with representatives of political parties in the Central African Republic.

(Photo: UN/Eskinder Debebe)

Arms embargoes have struggled to keep pace with all these dynamics. Part of the problem is that state capacity, political will, and experience varies considerably across countries, making it difficult to achieve the kind of coordination that can make embargoes more effective. Moreover, the complicated and constantly shifting networks of conflict actors, interests, and power dynamics within each conflict are not always considered in the design of arms embargoes and other types of sanctions, making it difficult to change the calculus of bad actors.

The obstacles to enforce embargoes have grown more challenging in recent years as certain UN Security Council members, notably Russia and China, have actively attempted to dilute sanctions, block expert panel nominations, and impede funding of the UN panels, especially when their reports have found these governments are engaged in violations. Rotating African members of the Security Council have similarly attempted to weaken enforcement. Rwanda, for example, blocked the designation of persons linked to embargo evasion as well as prevented the renewal of expert panel members who documented continued Rwandan support to M23 successor groups.

When They Work

Despite these problems, when applied creatively, arms embargoes and other types of sanctions can work. For example, the embargo against apartheid Rhodesia (South Africa) was carefully sequenced with additional measures, such as diplomatic and membership sanctions, cultural and sports boycotts, and travel bans. The apartheid regime had a well-developed domestic arms industry, and its imports were minimal. Other measures were necessary.

“Sanctions can also have a powerful deterrent effect, especially when they ostracize offenders and their alleged benefactors.”

Through an initiative by the Organization of African Unity (OAU), African passport holders could not travel to South Africa, thereby denying it tourist revenue as well as legitimacy as a travel destination. The OAU also succeeded in getting most member states to impose comprehensive boycotts of South African products, to deny landing rights for South African airlines, and to terminate academic exchanges. At the international level, the OAU persuaded many foreign governments and industries to divest from the South African economy, causing inflation to rise to between 12 and 15 percent annually throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Such measures, not the arms embargo per se, relegated South Africa to pariah status. The desire to end this isolation was one of the factors that pushed the National Party toward negotiations.

The practice of “naming and shaming” sanctions’ evaders has similarly been effective in other initiatives such as the effort to stop the trade in “blood diamonds” by requiring certification under the Kimberley Process. Sanctions can also have a powerful deterrent effect, especially when they ostracize offenders and their alleged benefactors.

Rwanda’s surprising move to place the renegade Congolese officer, General Laurent Nkunda, under indefinite house arrest in January 2009 after forcefully removing him from the battlefield is a case in point. Listed by the UN in 2005 for war crimes, Nkunda commanded a rebel force that many UN reports alleged was heavily backed by Rwanda. For years, Rwanda steadfastly denied the accusations but finally moved against Nkunda when donor partners withdrew aid. This followed the release of a damning UN report in December 2008. The timing suggests that cutting ties with Nkunda was a small price to pay to salvage Rwanda’s international reputation and restore donor confidence, an example of how sanctions can change the calculus of targeted actors under certain conditions.

Disarmament efforts in Burundi.

(Photo: UN/Martine Perret)

Embargoes can also be effective when countries work as coalitions. One example is the regional arms embargo against Burundi. It was imposed in August 1996 by seven states—the DRC, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia—following a coup in Burundi in July that threatened to frustrate peace talks launched by Tanzania. All exports were shut down and only medicines and humanitarian supplies could be imported. Meanwhile, the rebels were denied sanctuary in neighboring states and threatened with military action if they tried to recruit among refugee communities. Faced with such dire circumstances, the warring sides eventually (and reluctantly) entered negotiations that led to a peace deal in August 2000.

In another example, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) took swift coercive action against Côte d‘Ivoire in 2011 and The Gambia in 2017 when incumbents refused to leave office after losing elections. In both cases, ECOWAS 1) withdrew recognition, 2) cut off financial access, 3) closed travel links, 4) appointed high-level mediators, and 5) threatened military action. In The Gambia, ECOWAS went further by using military force to seal the country’s land and sea borders and deployed an intervention force. In all three instances, the defeated leaders of Burundi, Côte d‘Ivoire, and The Gambia were forced out and crises were averted.

“Sanctions can be made more effective when the motivations of key actors and their supporters are well understood, and their modes of survival are properly mapped and considered.”

Sanctions can be made more effective when the motivations of key actors and their supporters are well understood, and their modes of survival are properly mapped and considered. Many violators of arms embargoes are individuals who are motivated by localized concerns and issues, requiring considerable research.

These examples highlight the tactics that heighten the effectiveness of embargoes. First, the intervening states spoke with one voice and acted in concert. Second, their decisive leadership incentivized international partners to play complementary roles. Third, because of this unity of effort, targeted actors could not play one intervening state against the other. These lessons are relevant to ongoing assessments of the effectiveness of sanctions. Neighboring states in particular have a critical role to play in ensuring compliance with sanctions.

What Does the AU Say about Embargoes?

In March 2016, the AU Peace and Security Council met to establish why arms embargoes were not having the desired outcomes and how their impact could be increased. The findings of its final report are summarized below:

- There is need for coordinated action by regional states to enhance shared responsibilities.

- Arms embargoes are hampered by limited state capacity to monitor and enforce them—particularly regarding border control and information sharing among and between states and UN sanctions committees.

- Measures to curb weapons flows are increasingly occurring in the absence of formal peace agreements. Such situations require robust implementation and oversight mechanisms.

- Legally binding international instruments, such as the African Union Common Position on an Arms Trade Treaty, are the foundation for effective action. Further progress is required to achieve universality in Africa.

- Beyond legally binding international instruments, comprehensive legislative and regulatory frameworks are required at the national level. While existing legislation varies among member states, some are incomplete or outdated.

Takeaways

Arms embargoes can advance peace and security, especially when applied in combination with other deterrent measures in a comprehensive approach. In cases where they’ve been successful, sanctions have increased the costs to targeted actors by denting their reputations, undermining their international respectability, and denying them access to the international system.

Regional buy-in and ownership by immediate neighbors cannot be overstressed. The more coordinated countries are, the more difficult it is for violators to gain ground. However, embargoes should be customized to take each unique conflict dynamic into account as well as the behavior of the key actors and their tactics of evasion. For example, some bad actors evade sanctions by operating outside formal systems, however, they often need the patronage of those with such access. If their entanglements can be exposed, the larger conflict system in which they operate can be disrupted.

Additional Resources

- Colum Lynch, “Sunset for UN Sanctions?” Foreign Policy, October 14, 2021.

- Judith Vorrath, “Implementing and Enforcing UN Arms Embargoes: Lessons Learned from Various Conflict Contexts,” SWP Comment No. 23, German Institute for International and Security Affairs, May 2020.

- Paul Nantulya, “Lessons from Gambia on Effective Regional Security Cooperation,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 27, 2017.

- Nelson Alusala, “Towards effective implementation of UN-imposed arms embargoes in Africa,” Policy Brief, Institute for Security Studies, December 2016.

- Emile LeBrun and Christelle Rigual, “Monitoring UN Arms Embargoes: Observations from Panels of Experts,” Occasional Paper No. 33, Small Arms Survey, November 2016.

- Security Council Report, “UN Sanctions,” Special Research Report No. 3, New York, November 2013.

- Alix J. Boucher, “UN Panels of Experts and UN Peace Operations: Exploiting Synergies for Peacebuilding,” The Stimson Center, September 2010.

More on: Conflict Prevention or Mitigation Regional and International Security Cooperation