The Public Protector House in Pretoria, South Africa (Photo: Office of the Public Protector)The ongoing inquiry into the allegation that South African President Cyril Ramaphosa may have broken a string of South African laws when about $580,000 was found stuffed in a sofa in his Phala Phala luxury game ranch in February 2020 is a reminder of the perpetual challenge of holding senior government officials accountable. If true, the allegations would mean President Ramaphosa violated laws governing proceeds from foreign business transactions, the handling of foreign currency, prompt reporting of crimes, and ethics rules. Moreover, a parliamentary inquest found that Ramaphosa may have abused his power by tasking the head of his Presidential Protection Unit, rather than the police, to quietly track down the robbers.

“The multiple layers of inquiry and oversight of the South African executive branch … serve as a measure of accountability on powerful public officials.”

The charges come in the wake of the scandal-filled presidency of Jacob Zuma and widespread concerns that the government of South Africa was subject to state capture by private sector and foreign government influences. These debates remain trenchant as the ruling African National Congress (ANC) continues to undergo fierce internal battles over the future of the party between Zuma and Ramaphosa loyalists, including between those who allegedly benefitted from state capture and those who would like to restore the ANC—the party of Nelson Mandela and other exemplars of ethical leadership—to its former glory.

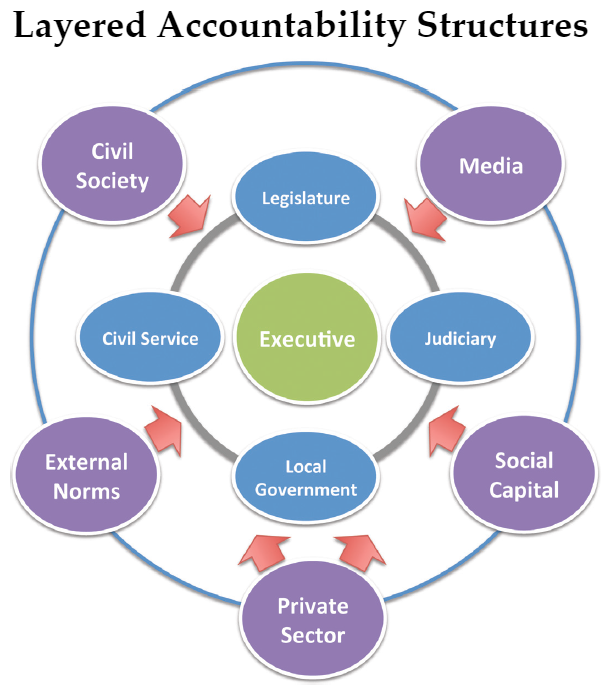

Often underappreciated in the back-and-forth of the so-called farmgate scandal are the multiple layers of inquiry and oversight of the South African executive branch that have helped raise public awareness of possible wrongdoing and which serve as a measure of accountability on powerful public officials. While incomplete and at times tenuous, these institutional checks and balances provide insight into South Africa’s democratic resiliency despite the dominance of the ANC—and offer a roadmap to other African countries seeking to strengthen accountability of senior government leaders.

South Africa’s Independent Institutions Tested Once Again

Upon taking office, Ramaphosa set his sights on strengthening South Africa’s oversight institutions as a matter of priority to remedy the widespread abuse of power and misuse of public resources under his predecessor.

He fulfilled a pledge to establish an independent Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture—a legally binding decision issued by the Public Protector in 2016 that the Zuma administration attempted to stall. Ramaphosa has taken on board all the findings and recommendations of this Commission. This includes a far-reaching 12-point program to create a new independent anticorruption agency with wide-ranging enforcement authorities, legislative amendments to make appointing the National Director of Public Prosecutions more transparent, new processes for selecting leaders and managers of state-owned enterprises, tightened loopholes around political party financing, sustained probes into a raft of government agencies, and the most extensive intelligence reform since 1994.

When the details of the farmgate episode came to light in 2022, multiple oversight mechanisms sprang into action—sometimes working collaboratively, sometimes in parallel.

A first layer of accountability is within the ruling party itself. The ANC’s Integrity Commission, which is empowered to independently investigate and sanction party leaders—including the ANC President—launched its own probe and summoned Ramaphosa to appear before it to explain himself. The Integrity Commission, by most accounts, took up this task resolutely. As one indication, at a briefing for the National Executive Committee (NEC), the Commission noted that the Phala Phala scandal was “one of 55 identified issues that had brought the ANC into disrepute.” However, rather than submitting its final report to the NEC, the Commission backtracked over a technicality: individuals under investigation (in this case Ramaphosa) are prohibited from discussing their cases before other bodies.

Residents confront ANC leadership at a townhall. (Photo: Ihsaan Haffejee)

South Africa’s Parliament, meanwhile, appointed an independent panel to investigate the matter in October 2022. Within a month of its creation, the panel found that President Ramaphosa actions had, in fact, raised the specter of improprieties that may have violated the law. Specifically, it questioned his explanation that the money was from the sale of buffaloes to a Sudanese businessman, asking why the animals were still on the farm more than 2 years later. It also found no evidence from the Treasury that the monies entered South Africa. Parliament also established that Ramaphosa did not report to the police as required, instead tasking the head of his protection detail to pursue the culprits. It concluded that the President put himself in a conflict of interest, adding that he “may be guilty of a serious violation of [certain sections] of the Constitution.” The report was debated in Parliament on December 14, 2022, but the ANC majority voted against adopting it (148 in favor, 214 against, and 2 abstentions). Some senior members of rival camps in the party simply stayed away.

South African legal experts familiar with the case note that the question for debate was misleading as it concerned itself with the mechanism of impeachment rather than the substance of the findings. Reflective of the multiple levels of accountability in South Africa, however, Parliament’s failure to pursue the case may open it to scrutiny and potential sanction by the Constitutional Court based on recent precedent. On December 29, 2017, this Court issued a landmark judgment that Parliament failed to hold former President Jacob Zuma accountable for a scandal over using public funds for a multimillion-dollar upgrade to his private home. The ruling set a constitutional standard for future cases involving the abuse of power.

Another independent institution, the Public Protector, launched a separate—and still ongoing—probe after receiving a complaint from individual members of the public that the President may have violated the Executive Members’ Ethics Act. In responding to questions from opposition deputies in October 2022, the Office of the Public Protector said it had received a “substantial amount of evidence from witnesses” and was proceeding with its investigations, which would be made public as required by law. The Public Protector can investigate any office or official. This can be initiated by aggrieved persons or organizations—even individual citizens. Unlike other public protectors in other African countries and other parts of the world, the findings of South Africa’s Public Protector are legally binding.

The Limpopo provincial office of the Public Protector. (Photo: Office of the Public Protector)

During the Zuma presidency the Public Protector conducted two groundbreaking investigations resulting in two important reports: “Secure in Comfort,” on the abuse of taxpayer money for security upgrades in Zuma’s private home, and “State Capture,” on the systematic seizure of state institutions and resources by private interests linked to Zuma. These two investigations set into motion numerous, concurrent legal and constitutional processes that eventually led to Zuma’s removal as President, and ultimately to jail. Having served his prison sentence for contempt of court, he now awaits the continuation of his corruption trial.

Opposition parties, another critical layer of accountability in a democracy, plan to petition the courts, harkening back to the strategic litigation initiatives launched against the Zuma presidency. The Constitutional Court heard an application by President Ramaphosa to set aside the parliamentary report on the grounds that it is unlawful. The African Transformation Movement (ATM), a political party with roots in the South African Council of Churches, filed a countermotion arguing that Ramaphosa had not exhausted lower court remedies and that the report in any case cannot be set aside as it merely contains recommendations and is therefore nonbinding. The Constitutional Court subsequently ruled that the president failed to make the case for why the Court should intervene, validating the position of the ATM and civil society that the findings of the Phala Phala report should be exhausted through parliamentary debate.

ATM also asked the Western Cape High Court to declare the Speaker’s decision to refuse an opposition request for a secret ballot unlawful and unconstitutional. Instead, ATM is calling on the Court to substitute this decision with a directive that members be allowed to vote via secret ballet on the report (thereby mitigating ANC pressure on members to absolve Ramaphosa of any wrongdoing).

The petitions by civil society and the opposition to the courts attests to the perceived independence of the judiciary—among the most trusted institutions in South Africa.

Concurrent to these official means of oversight, media outlets continue to conduct their own investigations. Demanding the transparency expected of democratic governments, the South African media has a well-earned reputation for independent reporting and a demonstrated investigative capacity. Its role in the accountability process is often iterative with media agencies helping to trigger the earlier Public Protector’s investigations into state capture. The media’s round-the-clock coverage of the public hearings conducted by the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture helped inform the public of the extent of state capture and galvanized civil society, including churches, trade unions, lawyers’ associations, and grassroots groups like the Save South Africa movement.

“Public accountability does not rest with a single entity or individual.”

The web of official and unofficial oversight mechanisms in South Africa highlights that public accountability does not rest with a single entity or individual. If one oversight mechanism should fail to adequately serve as a check on potential irregularities, then other bodies can step in. In South Africa, to counterbalance the ANC-dominated Parliament and the ANC’s Integrity Commission, which have so far lost the public’s confidence to hold the executive accountable, ordinary South Africans are relying on their tried-and-tested methods of media engagement and outreach, strategic litigation, independent petitioning, and unscripted civil society debates.

These tactics date back to nonviolent mass action against apartheid and were refocused on preserving democracy and holding post-apartheid governments and the ANC itself to account. It should be recalled that the South African government faced such pressures even during the Nelson Mandela administration. In fact, the original probe into a controversial $2 billion defense procurement contract included in Zuma’s charge sheet has been ongoing since the administration of Thabo Mbeki (in which Zuma was Deputy President). This came about from coordinated and sustained civil society oversight, which included a string of strategic litigation cases.

Some South Africans have taken the position that, given Ramaphosa’s reformist credentials, any investigations should be minimized. Civil society and retired stalwarts take a different view. For them, the idea that Ramaphosa should be excused because he is the best among South Africa’s more corrupt alternatives is deeply flawed and indicative of the crisis facing the ANC. They argue that misconduct in office should be unacceptable under any circumstances, otherwise the principle of accountability loses all meaning.

Adapted from Joseph Siegle, “Building Democratic Accountability in Areas of Limited Statehood.”

Implications for South Africa Moving Forward

To be sure, South Africa faces a serious governance crisis. Even Ramaphosa’s most dedicated supporters agree that his presidency has been damaged by the farmgate allegations. Nonetheless, South Africa benefits from the potential for self-correction given its traditions of civic activism, public engagement, and a sophisticated and independent civil society and media.

The nature and levels of public engagement are such that not even the ANC is impervious to this environment. Responding to public displeasure of previous leaders’ actions, the ANC reacted to pressure from below by removing two presidents in a row, Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma. Few other governing parties around the world can claim this.

Desmond Tutu joins other religious leaders and a wide range of civil society groups in a 2014 march called “Procession of Witness” in defense of the role of the Public Protector. (Photo: AFP / Rodger Bosch)

Ultimately, it was public discontent and civic activism that forced the ANC to act. This points to the critical role of civil vigilance. South Africans coined the popular phrases “eternal vigilance” and “informed mass action” that shaped the culture of protest, democratic traditions, and strategic engagement rooted in the mass struggle against apartheid. These traditions informed the ANC’s formative culture. Yet civil society resisted attempts to be co-opted and has retained its independence and refined its tactics.

Because of having developed hard-earned institutions of accountability, the ongoing battle for the soul of South Africa is, once again, largely in the hands of South Africans. As long as they retain such high levels of informed engagement, the country has the prospect of turning a moment of scandal into an opportunity for transformation. The South African public has proven repeatedly that it is unafraid of uncomfortable conversations and sees itself as a custodian of the Constitution. Such an approach, along with the effort to strengthen a dense web of accountability institutions, is a lesson not just for other countries in Africa but elsewhere around the world.

Additional Resources

- Thabo Leshilo, “ANC in Crisis: South Africa’s Governing Party is Fighting to Stay Relevant – 5 Essential Reads,” The Conversation, December 15, 2022.

- Jakkie Cilliers, “What Does a Wounded ANC Mean for South Africa’s Prospects?” ISS Today, December 6, 2022.

- Ivor Chipkin, “Phala Phala is Not a Crisis for South Africa; It is a Crisis for Cyril Ramaphosa and the ANC,” Daily Maverick, December 4, 2022.

- Paul Nantulya, “South Africa’s Democracy Is Put to the Test,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 23, 2017.

- Joseph Siegle, “Building Democratic Accountability in Areas of Limited Statehood,” paper presented at the International Studies Association Annual Meeting, “Power, Principles, and Participation in the Global Information Age,” March 27, 2012.

More on: Democracy