The 1918 “Spanish flu” pandemic brought death and disruption across the globe, infecting an estimated 500 million people (about a third of the world’s population) and killing 20-50 million. The severity of the pandemic’s toll was particularly acute in Africa, much of which was under colonial administration. Nearly 2 percent of Africa’s population is estimated to have died within 6 months—2.5 million out of an estimated 130 million. The Spanish flu tore through communities, in some cases infecting up to 90 percent of the population and generating mortality rates of 15 percent.

The pandemic’s impact on South Africa is particularly notable, as it was one of the five worst hit parts of the world. Roughly 5 percent of South Africa’s population perished. When the Spanish flu emerged in West Africa, the speed at which the virus ravaged Freetown, Sierra Leone, was staggering. Four percent of Freetown’s population died in just 3 weeks. In East Africa, the pandemic killed 4-6 percent of Kenya’s population over 9 months. In many parts of the continent, medical facilities were overwhelmed.

While both the pandemic of 1918 and COVID-19 are respiratory diseases largely spread through the air by coughing or sneezing, the two pandemics are different in important ways. The H1N1 influenza strain of 1918 had a very short incubation period—just 1 to 2 days—whereas the coronavirus incubation can stretch up to 2 weeks, and its spread is facilitated by asymptomatic carriers. Moreover, the flu pandemic of a century ago would penetrate deep into a victim’s lungs straightaway, and its virulence could trigger an overreaction by the immune system, filling the lungs with antibodies that caused acute respiratory distress. As a result, victims were overwhelmingly the young and healthy. This is the inverse of COVID-19’s age profile, which targets those with weakened immune systems. Despite these differences, lessons from the deadly pandemic of 1918 bear heeding today.

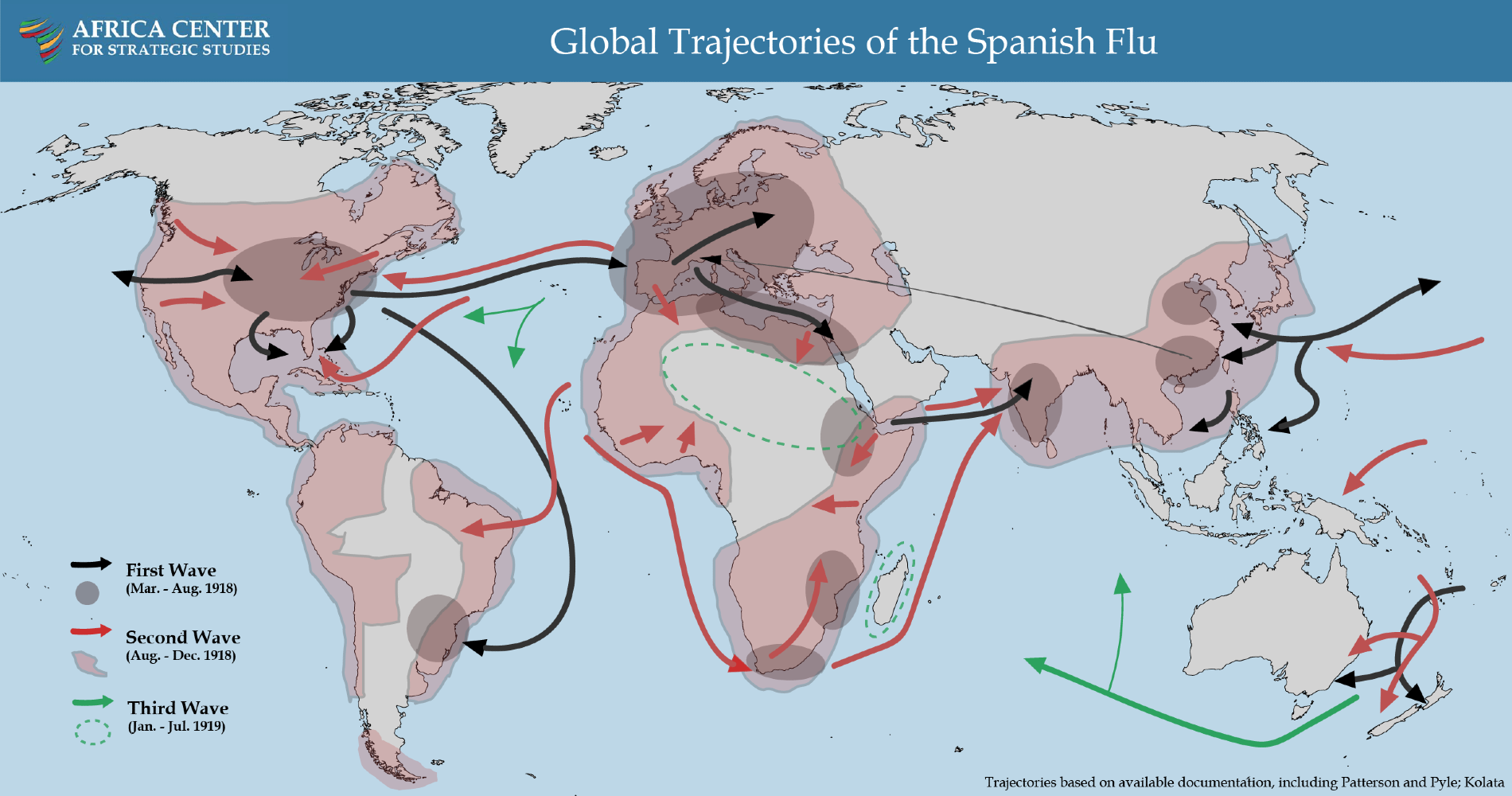

Three Waves of Varying Intensity

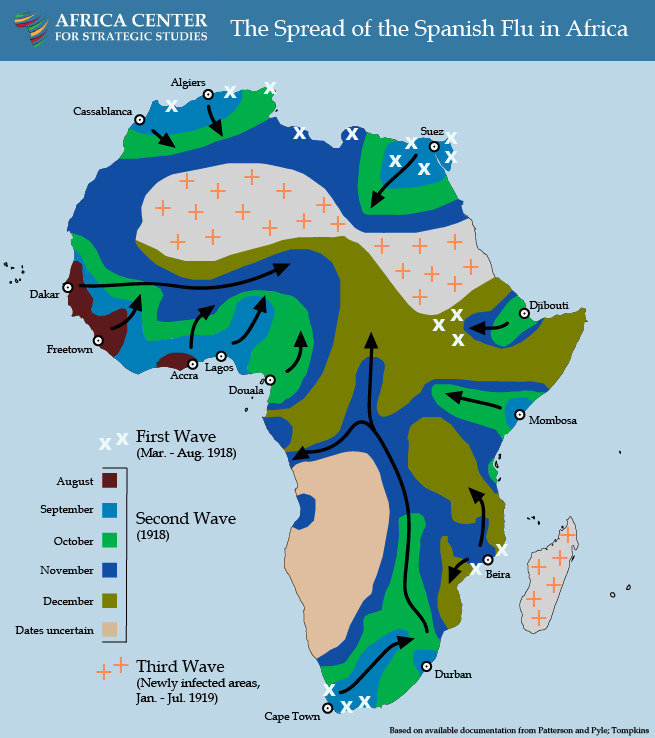

The pandemic of 1918 had three distinct but iterative waves. From March through July 1918, the relatively mild first wave swept through most regions of the world, spread initially by troop movements during World War I. Beginning in May 1918, colonial reports document the spread of the disease in North Africa starting from the Mediterranean coastal cities. Only North Africa, Abyssinia (Ethiopia), South Africa, and Portuguese East Africa reported infections during this phase. Sub-Saharan Africa was largely spared.

The virus is believed to have then mutated into a significantly more infectious and lethal strain, resulting in a second wave that began in August 1918. This deadly second wave arrived in sub-Saharan Africa via the seaports of West Africa and spread like wildfire through Sierra Leone, Ghana, Nigeria, The Gambia, and Cameroon. Ships carrying infected persons reached Southern Africa by late September-October 1918. The ports of Mombasa and Djibouti were simultaneously the points of exposure for East Africa.

Countries that were exposed to the mild first wave seemed to experience a reduced impact during the second wave, even though the two strains were markedly different. Having largely escaped the mild first wave, accordingly, Africa was particularly vulnerable to the virulent second wave.

As the second wave wound down in December 1918, a third wave began the following month, compounding the devastation.

Factors That Facilitated the Transmission

World War I played a significant role in transmitting the virus rapidly and globally. Ships transporting some of the 150,000 African troops and 1.4 million laborers providing logistics support to the war in Europe brought the Spanish flu to the seaports of Freetown, Cape Town, and Mombasa.

Nigerian regiment returning to Lagos in 1918. (Photo: uncensoredopinion.co.za)

Urban centers on the coast—areas with well-developed transportation networks largely created to facilitate mineral extraction—transmitted the 1918-1919 flu inland along rivers, roads, and railway systems. The railway lines in particular served as an accelerant, spreading the disease more than 100 kilometers a day.

Panicked responses to the sickness and death that engulfed population centers on the coast led to an exodus of newly demobilized soldiers, families, and migrant workers to rural areas. Within 3 months, the influenza virus had reached deep into central Africa.

Similar effects were reported from Abyssinia, one of the few independent African states at the time, where the Spanish flu is remembered as Hedar Basita (disease of the Ethiopian month of Hedar, October/November). The disease moved rapidly from the coast to Addis Ababa and beyond, claiming lives from all social classes, including priests and national leaders. The effects were compounded by the heavy toll the pandemic took on the country’s few doctors. This contributed to a general sense of disorder and disruption with many people, including government leaders, fleeing the towns.

According to South African historian Howard Phillips, the African countries hardest hit by the disease—South Africa, Kenya, Cameroon, Gold Coast (Ghana), The Gambia, Tanganyika (Tanzania), and Nyasaland (Malawi)—shared three characteristics: “first exposure to the pandemic only in its most virulent, second-wave form; being part of an extensive transport network by sea or by land; [and] being regularly traversed by large numbers of people on the move, such as soldiers, sailors, and migrant workers.“

Effective Responses

Without a vaccine or cure, much of the response focused on mitigating the spread through social distancing and quarantines. Schools, churches, markets, and roads were ordered to be closed, and bans on large public gatherings were implemented. In some instances, empty schools and churches were used as makeshift hospitals. In coastal towns, officials monitored the points of entry, inspected ships for cases of infections, and imposed quarantines. Places such as Zanzibar and Nyasaland enacted strict quarantine measures and contact tracing practices to slow the spread. The efforts of these two governments were heralded as some of the most comprehensive on the continent.

Early communication and information sharing, furthermore, were vital to response efforts. The radio and telegraph were used as early-warning communication tools to alert medical authorities of incoming ships known to be carrying the Spanish flu. In Swaziland, village chiefs informed locals of the impending arrival of the virus and made announcements that medicine would be available at certain health centers.

In Lagos, health authorities resorted to issuing “government medical passes” in order to monitor and trace infected individuals. But as the number of cases increased and the system became too hard to manage, a mass exodus began. The colonial government then appealed to the local chiefs and used The Nigerian Pioneer newspaper to urgently request that people cooperate with the health authorities. Similarly, in Lagos, the most successful efforts occurred when British doctors called a meeting to listen to the suggestions of African medical practitioners (who were otherwise excluded from colonial service on the basis of race). Among other measures, this led to printing and circulating preventative guidance in both Yoruba and English.

“Early communication and information sharing were vital.”

Public health workers and volunteers focused their efforts on opening temporary emergency hospitals, soup kitchens, and relief depots that provided food and medicine. Volunteers cleaned areas where outbreaks had occurred. People across the class and racial divides responded to this call. In some areas of South Africa where public health facilities were overwhelmed, towns were divided into districts with one doctor assigned per district, irrespective of who their regular doctor was.

By contrast, one response proved particularly unhelpful: house-to-house searches. The Health Ordinance of 1917 in Lagos gave British medical authorities legal mandate to enter private homes in search of those infected. The intrusions were unprecedented and created a sense of panic and fear. People began to run away, further spreading the influenza and thereby making efforts to trace those infected an impossibility. For those who chose to stay and not run, many who were sick tried to hide their illness for fear of being sent away to hospitals for treatment, where they would be isolated from their family. Others feared their property would be taken by the colonial authorities if they had to be sent away to the hospital. Still others feared the medicine was poison. In Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), running away and hiding became a common reaction by locals upon hearing someone was coming to provide medicine.

In short, because of the lack of trust and misunderstanding, the house-to-house visits were both ineffective and counterproductive. This was compounded by the lack of clear communication about the initiative, which allowed suspicion and mistrust to flourish, despite medical officers’ attempts to offer some relief and slow the spread.

Impacts on Africa

Of the consequences caused by the pandemic, the sharp drop in food production in 1919 was among the most significant. Many regions across Africa experienced famine or near-famine conditions due to the disruptions to food production in 1918. It subsequently gave rise to adaptations in agricultural methods and social preferences. In Nigeria, there was a switch to cassava instead of yams, given that the former could be grown year-round and was also less labor-intensive. In other parts of Africa, new varieties of quick-growing maize and beans were introduced to avoid future famines.

Labor shortages were also a significant repercussion of the pandemic. All sectors of the economy were impacted, leading to paralysis and acute disruption of all routine activities. Public services such as transportation, mail delivery, policing, and schooling were halted or severely disrupted, and businesses struggled to stay afloat with minimal staff.

The pandemic also had a devastating effect on family structures as young and healthy adults died in extraordinary numbers, leaving 10 to 12 million orphans across the continent.

Beds for patients with the Spanish flu. (Photo: CDC)

Takeaways from Africa’s Experience with the Pandemic of 1918-1919

Africa is a key focal point of global health security. Africa has long been central to global shipping routes and, therefore, a central battleground for pandemics. Indeed, ports were a key means of transmission for the Spanish flu in Africa a century ago. And, today, global ties for commercial, travel, and security interests have elevated Africa’s exposure to COVID-19. The experiences from these pandemics reinforce the reality that all countries are part of a connected global community and must collectively face such transnational threats.

Social distancing and behavior change have an impact. The experience of the pandemic of 1918-1919 showed that societies that were able to implement guidelines regarding social distancing, limiting mobility, and personal hygiene were better able to mitigate community transmission of the virus. In an attempt to check the spread of the Spanish flu, schools, churches, mosques, cinemas, and markets were closed down or, where suitable, used as hospitals. Large public meetings were prohibited. While these measures were not cures, they were useful for slowing transmissions and limiting the impacts of the disease.

Communication matters more than ever in times of crisis. Jurisdictions that communicated regularly and honestly with their public raised awareness, enabled public health preparations, and reduced the spread of rumors. This concerted effort to share information educated populations on public health efforts undertaken and solicited greater cooperation, while reducing panic. The use of newspapers and telegraph, for example, alerted communities up-country that the virus was on the way and what to expect. Coordination with traditional leaders, meanwhile, was vital for communicating with many local communities.

Trust is indispensable. The degree to which local communities trusted authorities was directly linked to their willingness to cooperate with public health efforts. In some jurisdictions, residents feared colonial authorities would seize a household’s property, assets, or land if they acknowledged they were sick or went to the hospital. This greatly constrained the reporting and tracing of the pandemic.

“Africa is a focal point of global health security.”

Protect public health professionals. As today, the response to the pandemic of 1918-1919 was marked by heroic efforts by health professionals to serve the public in the face of the crisis by treating those who were sick, organizing a coordinated response, and reporting on the outcomes of their efforts so as to accelerate learning among the broader health community. These efforts point to the importance of providing protections for health professionals who are the frontline of defense against the pandemic. If they are immobilized, the broader society is at greater risk. During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, it is estimated that 8 percent of Liberia’s health personnel perished.

Action must be taken to ensure food security. A vital takeaway from the Spanish flu experience in Africa is that the pandemic decimated the food supply not only during its spread but also over the subsequent 2 years by disrupting production, transportation, and markets. This represents a serious compounding risk that may threaten millions. National leaders will need to assess how food supply chains will be affected over the coming year to ensure farmers have incentives to produce and that transportation, storage, and processing facilities are operational. Vulnerable households will also need to have sufficient income so that they can access essential food products in local markets.

Responding to a pandemic is a marathon that will take unexpected turns. The experience of a century ago underscores that pandemics can endure for an extended timeframe—in that case over a 2-year period. This was marked by three different waves, a mutation of the virus, and differing transmission trajectories for each wave. National leaders and public health officials, therefore, need to be prepared for a long challenge and develop a strategy for a protracted response that will likely need to be adapted over time.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “African Adaptations to the COVID-19 Response,” Spotlight, April 15, 2020.

- Mark Duerksen, “Innovations Needed to Prevent COVID-19 from Catching Fire in Africa’s Cities,”Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 9, 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Mapping Risk Factors for the Spread of COVID-19 in Africa,” Infographic, April 3, 2020.

- Shannon Smith, “Managing Health and Economic Priorities as the COVID-19 Pandemic Spreads through Africa,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 30, 2020.

- Fred Andayi, Sandra S. Chaves, and Marc-Alain Widdowson, “Impact of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic in Coastal Kenya,” Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 4, No. 2, 2019.

- Jimoh Mufutau Oluwasegun, “Managing Epidemic: The British Approach to 1918-1919 Influenza in Lagos,” Journal of Asian and African Studies 52, No. 4, 2015.

- Howard Phillips, “Influenza Pandemic (Africa),” International Encyclopedia of the First World War, October 8, 2014.

- Juergen D. Mueller, “Patterns of Reaction to a Demographic Crisis. The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Research Proposal and Preliminary Regional and Comparative Findings,” Staff Seminar Paper No. 6, April 1995.

- Sandra M. Tomkins, “Colonial Administration in British Africa during the Influenza Epidemic of 1918-19,” Canadian Journal of African Studies 28, No. 1, 1994.

- K. David Patterson and Gerald F. Pyle, “The Geography and Mortality of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 65, No. 1, 1991.

- K. David Patterson and Gerald F. Pyle, “The Diffusion of Influenza in Sub-Saharan Africa during the 1918-1919 Pandemic,” Social Science and Medicine, No. 17, 1983.

- D. C. Ohadike, “The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19 and the Spread of Cassava Cultivation on the Lower Niger: A Study in Historical Linkages,” Journal of African History, January 22, 1981.

More on: Africa Security Trends COVID-19 Health & Security