The densely populated hills of Kampala, Uganda. (Photo: Mark Duerksen)

COVID-19 spreads at close range through respiratory droplets. Consequently, the most serious outbreaks of the pandemic have been seen in dense settings and close-knit social networks. With household and core urban densities among the world’s highest, African cities have the potential to serve as deadly incubators for the virus’s spread.

Fragility, Density, and the Need for Novel Solutions in African Cities

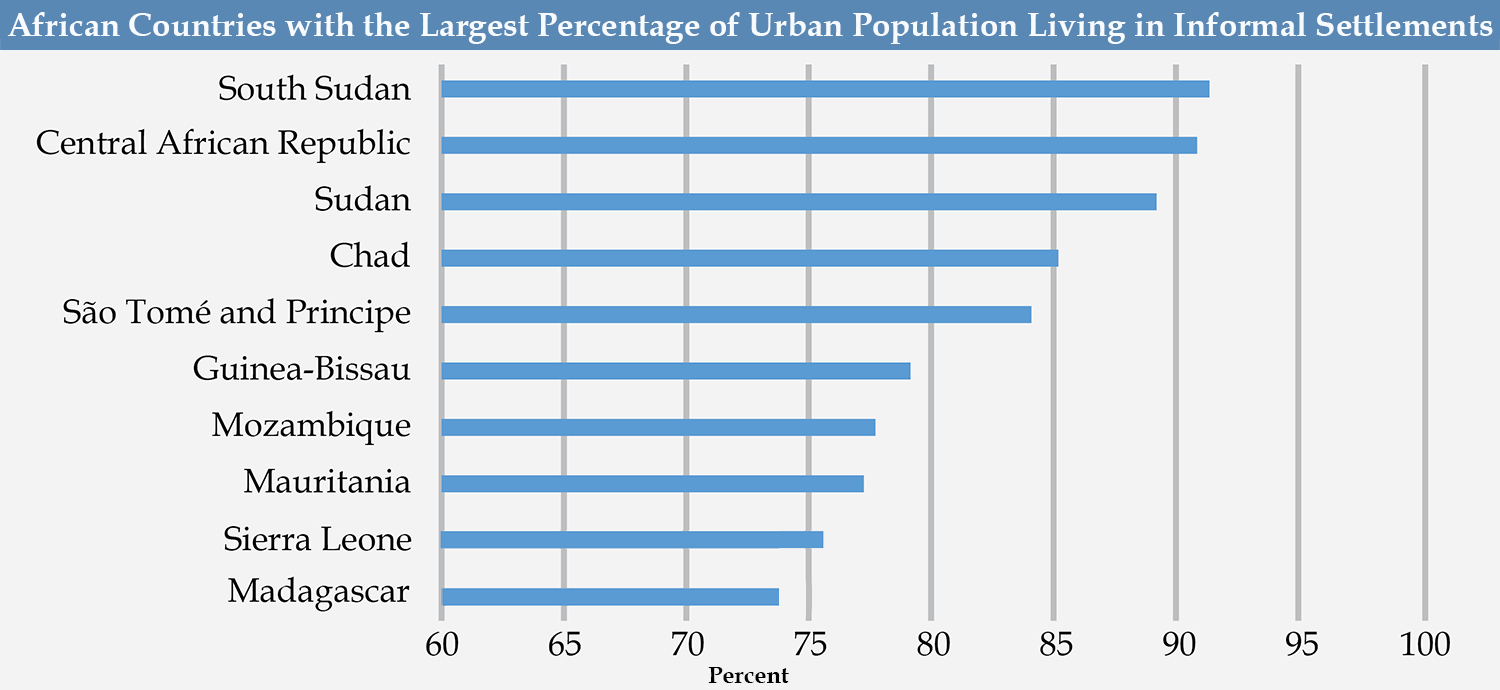

Over half of urban Africans—more than 200 million people—live in informal neighborhoods where such vulnerable conditions persist and are magnified by limited access to water and sanitation. In countries like South Sudan, the Central African Republic, and Chad, nearly 9 out of 10 urban residents live in informal settlements. Some of the largest of these settlements number several hundred thousand people, including Kibera in Nairobi, Manshiyat Nasser in Cairo, and Khayelitsha in Cape Town. The population densities of these communities are frequently over 75,000 people per square kilometer. In Cairo’s densest areas, nearly 1,000 people make their homes in spaces the size of a soccer field. In Nigeria, an average of over three people sleep in every room. This number is doubled in some Nigerian cities. At least five million households in Lagos are homeless or lack adequate shelter.

Problems and proximities like these not only compound the spread of COVID-19 but also amplify the challenge of isolating at home. Africa’s responses, accordingly, will need to be carefully tailored to the continent’s unique urban landscapes.

Data Source: UNDESA

Africa’s Diverse Urban Landscapes

In assessing COVID-19-related risks in Africa’s urban areas, two defining features are particularly relevant: urban density and total urban population. Urban density shows the average number of people per kilometer in towns and cities within a country. Generally, greater density presents a problem for implementing social distancing. Total urban population captures the total population of people living in a country’s towns and cities and, therefore, reflects the number of people at higher risk for catching and spreading the coronavirus. Larger populations represent greater challenges in tracing the circulation of infected people. These patterns of population distribution overlap in different ways and manifest in a diversity of urban landscapes in Africa. This, in turn, will require different priorities and responses for battling COVID-19.

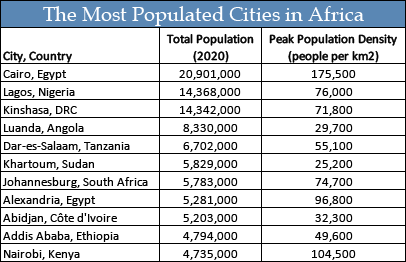

Megacities. Africa’s largest cities have grown relentlessly for decades to become home to tens of millions of people spread between overcrowded central settlements and offshoots of similarly unplanned sprawl and satellite towns. Primate cites like Lagos, Kinshasa-Brazzaville, Cairo, and Dar-es-Salaam present the challenges of both high densities and high populations. However, these cities have experience battling disease outbreaks, and many have worked with national agencies to set up capable public health systems and emergency operation centers before the first COVID-19 cases were confirmed. Vigilance in communicating, monitoring, and tracing by these initiatives will be critical for mitigating the number of confirmed cases in many African megacities.

Cairo, an early hotspot of COVID-19 in Africa. (Photo: Sebastian Horndasch)

Data: UN DESA, EC JRC, CIESIN

Secondary Cities. While Africa’s global cities attract the most international media coverage, the majority of urban Africans live in small and medium-sized cities ranging from a hundred thousand to several million residents. There are nearly 500 of these cities dispersed across the continent. Every single one—from cities like Bangui to Cotonou to Durban to Tunis—faces its own hurdles in tackling the pandemic, ranging from complications of post-conflict reconstruction to economic contraction caused by the crisis. Furthermore, these population centers may not have the same levels of health resources or expertise as the continent’s largest cities. Special attention and international support may be necessary to prevent these cities from suddenly becoming coronavirus hotspots.

Durban, one of Africa’s busiest port cities, which has been hard hit by COVID-19. (Photo: Google Maps)

Cattle-herding in a peri-urban neighborhood in Calavi, Benin. (Photo: Mark Duerksen)

Peri-Urban Sprawl. In regions with high levels of unplanned urbanization like the West African coastline or the highlands of Ethiopia, landscapes are often a mosaic of lower density but nonetheless heavily built-up settlements stretching between denser population hubs. These areas are marked by high levels of mobility as residents commute for work, errands, and social engagements. As a result, these regions have the potential to fan the virus far and wide beyond city centers. Many peri-urban plots and compounds have a degree of self-sufficiency (e.g., bore-holes, solar-panels, septic tanks, and urban gardens), which may allow their residents to isolate if they are willing. These less dense regions may also be able to absorb populations from denser downtowns as people leave city centers to stay with relatives or friends during the coronavirus outbreak.

Clustered Cities. These cities are very dense and are defined by the steep population drop-off in the surrounding countryside. Unlike sprawling megacities, the edges of clustered cities are more readily discernable. In cities across the Sahel, from Dakar to Khartoum, populations have historically clustered in market towns and capital cities like Nouakchott or N’Djamena, seeking walled shelter from the harsh surrounding landscapes and, increasingly, from violent extremism.

While not many are among the continent’s largest cities, these constricted settlements risk kindling outbreaks like those being experienced in the similarly dense cities of Spain and Italy where it is more difficult to fan out to reduce peak densities. From Angola to Uganda, many African countries exhibit patterns of urban clustering higher than Europe and the United States. Yet, within several miles of the centers of clustered cities like Gulu or Luanda, vast expanses of rural hinterlands appear. Thus, these countries and municipalities will need to concentrate their prevention efforts on these relatively small geographical nodes of urban density. They should face less difficulty stringently tracing the contacts of people confirmed to have the virus. More difficult will be creating social distancing within such dense cities. Creative solutions, therefore, are necessary to stagger the number of people in public spaces at any given time.

N’Djamena’s compact urbanism. (Images: Google Earth)

Niamey’s built-up streets. (Photo: Google Earth)

Fractured Cities. Disparities between impoverished and well-off urban residents are pronounced in most African cities, particularly in many former colonial cities that were segregated by race. The former “African” areas of these cities were rarely provided with planned infrastructure or other state resources. In places like Nairobi, where 59 percent of the city does not have access to potable water, organized cartels control access to water and sanitation in informal settlements and may take advantage of the pandemic to further escalate already high prices.

These disparities are clearly visible in the contrasting densities that distinguish privileged from precarious parts of town. Rather than quarantining and, thus, possibly stigmatizing entire low-income communities perceived to be at higher risk for developing the virus, resources and care must be prioritized for these areas.

Kibera, Nairobi, bordering upscale developments and a golf course. (Photo: Google Earth)

Sharp Influx to Cities. All of Africa’s urban landscapes are shaped by the phenomenon of rapid growth. The total population of African cities has doubled in the past 20 years to nearly half a billion people. The development of infrastructure, government services, and housing has lagged making it harder for municipalities to prepare for pandemics. “Push” factors—such as war, drought, and the economic marginalization of rural areas—rather than “pull” factors have significantly contributed to this. Many African cities have swelled with people displaced by desperate situations. Arriving with few resources and looking for security, these people often end up in informal settlements and in exploitative situations with few options. Already stigmatized in some communities as “outsiders,” displaced people in urban settings are particularly vulnerable to suffering during the COVID-19 outbreak.

These five urban landscapes are not static or self-contained. They overlap, form hybrids, and are all characterized by population movement, including those who have been forcibly displaced. The categorization of these landscapes provides a starting point for analyzing urban population distributions in Africa and for understanding what problems exist, what is possible, and what to prioritize. Also needed, however, are insights into the networks, relationships, and channels that connect and sustain vulnerable people living in these cities. People and social capital are often African cities’ most valuable assets and must be safeguarded if these cities are to recover and rebuild stronger. Leveraging these connections to communicate public health messages will go farther than trying to force separation by setting up barriers or confining impoverished people to their homes indefinitely.

Pragmatic African Urban Innovations for Responding to COVID-19

African cities are historically resilient and will need to pursue creative measures that prioritize the basic health and survival needs of these communities to flatten the curve of the coronavirus. Following are some of the best practices and innovations that have been employed.

Best Practices for Urban Crisis Management

- The UN has underscored the reasons why focusing on the most vulnerable is an imperative on both humanitarian and public health grounds, emphasizing that cities and global systems are only as strong as their weakest points. Waves of the virus and economic paralysis could return from unassisted areas if solidarity is not the strategy.

- UN Habitat has stressed the important role of mayors and governors in the crisis and the need for integrated and local approaches.

- UN Habitat has also emphasized protecting residents in informal settlements by stopping forced evictions and “de-densification” programs.

- The Center for Disease Control and Prevention has highlighted the role that “super-spreader” events play in the spread of COVID-19 and the need for cities to reduce the likelihood of such events in enclosed spaces like packed buses, indoor markets, and houses of worship.

- USAID has developed an extensive toolkit for municipalities to establish priority actions and communication strategies during pandemic stages of preparedness, response, and recovery. Particularly useful for African cities are tools on how to gauge and map food security risks within a city in order to allocate food resources.

- NextBillion has provided strategies for implementing cash transfer programs during the pandemic, beginning with mapping “communities that are most in need of health and financial support,” which will often be in dense urban areas.

- Many experts have noted that the empowerment of already present and trusted community organizations and local leaders will be critical to reach the most vulnerable, as was the case during the Ebola outbreaks in West Africa and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Civil society groups in informal settlements know their communities and have health strategies in place that should be supported rather than interrupted.

Innovative Responses in African Cities

“African cities are historically resilient.”

A number of African cities have already adopted innovative responses to the pandemic. Funding is an obvious limiting factor for some of these programs and may be a way the involvement of international actors could make an immediate impact. With the informal economy representing at least a third of official output in many African economies, stabilizing African urban areas means targeting the most vulnerable residents.

- While lockdowns are the most direct way to limit mobility, these are not sustainable in poor urban settings. Accordingly, some efforts have been made to link lockdowns with cash transfers to vulnerable citizens so that they have the means to survive. Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa are either instituting or scaling up these types of cash transfers through mobile money credits or direct deposits.

- Nigeria, which has the most people living in extreme poverty in the world, has started distributing 2-month grant advances to its poorest citizens. Prior to the pandemic, direct payment programs were shown to reduce poverty more effectively and efficiently than many social programs in South Africa.

- Many municipalities are encouraging people to move to cash-free transactions to prevent the in-person spread of the virus.

- Municipalities in South Africa are now permitting some informal markets that low-income residents rely on for food to continue operating, and some have been moved to new locations with more room for spreading out vendors’ stalls.

- Meal provision programs, handwashing stations (water and soap are unaffordable for many residents), and the suspension of water utility charges are similarly helping blunt the health impact of an economic standstill in African cities’ poorest settlements.

- Public health messaging regarding the importance of social distancing and proper hygiene measures is critical and difficult in areas where there is a historical “trust deficit” between people and governments. Tapping community organizations and faith-based groups to help convey these messages has worked to fight myths and misinformation and to increase social pressure for behavioral change. In urban areas, videos by entertainers and public announcements by celebrities are also helping to reach youth and shift behaviors. A coronavirus awareness song recorded by Uganda’s Bobi Wine and Nubian Li has been viewed nearly a million times. As one lyric says, “the bad news is that everyone is a potential victim, but the good news is that everyone is a potential solution.”

- Many cities are allowing people to continue using public transportation to get to work for essential jobs or to access food and other supplies. However, authorities are limiting the maximum capacity of buses and vans and providing hand sanitizers.

- South Africa is mobilizing field health workers who will be conducting extensive mobile testing. This plan will reduce the movement of potentially infected people. For those who test positive and face difficulties self-isolating at home, some cities are setting up isolation centers in soccer stadiums and parks.

- More challenging will be managing the flow of people in and out of cities. Kenya has now sealed off Nairobi and Mombasa. At some point, given the unsustainability of lockdowns, allowing people to leave cities to social distance with relatives or at second homes in rural areas could reduce pressure on crowded downtowns. (This pattern may be preventing a worse spread in places like New York). This has long been a strategy in Yoruba-speaking cities to manage disease outbreaks and is partially credited for the success and extent of urbanization in southwest Nigeria. However, municipalities will need to develop systems to test people before they leave to prevent spreading the virus to rural populations where health facilities may be lacking, and monitoring may be more difficult.

“Social pressure rather than soldiers will ultimately be more likely to bring about social distancing.”

Using the Security Sector Effectively. Reports of heavy-handed and even deadly enforcement of lockdowns by Kenyan, South African, and Zimbabwean security forces have made headlines. Urban African populations already have among the highest levels of fear of violence in the world and often mistrust local police. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa has asked troops to be a “force of kindness.” Social pressure rather than soldiers will ultimately be more likely to bring about social distancing.

The military and police forces would be better used to secure places like testing centers, hospitals, and health care workers if needed. Additionally, police may be deployed to protect women and children who are facing increased domestic violence while confined at home. There were 90,000 reports of violence against women and children in South Africa during the second weekend of the national lockdown. Quick police responses and direct cash transfers may help reduce some of these strains while protecting the most vulnerable.

A Moment for Mercy and Urban Opportunity

“These lessons from history demonstrate the importance of building more inclusive and … more secure cities and urban health programs.”

This is not the first time a pandemic has hit African cities. In fact, epidemics have played a formative role in African urbanism—from the historically mobile capitals of Buganda and Ethiopia to the development of Zongos (traveler and merchants’ quarters) in West Africa. The colonial history of African cities is replete with deadly plagues, flus, and fevers, precisely because the colonial governments placed little priority on the conditions of the city’s most vulnerable—their segregated and cramped “African” neighborhoods. Preventable postcolonial epidemics, like Zimbabwe’s 2008-2009 cholera outbreak, have likewise occurred when authoritarian African governments have politicized public health systems and responses.

These lessons from history demonstrate the importance of building more inclusive and, therefore, more secure cities and urban health programs in Africa. Responses to the arrival of COVID-19 provide an opportunity to spur this process of inclusion with regard to food, financial, and physical security. In the process, it will shape the future of African cities, making them more resilient to the next shock.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Mapping Risk Factors for the Spread of COVID-19 in Africa,” Infographic, April 3, 2020.

- Shannon Smith, “Managing Health and Economic Priorities as the COVID-19 Pandemic Spreads through Africa,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 30, 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Five Myths about Coronavirus in Africa,” Spotlight, March 27, 2020.

- Wendy Williams, “COVID-19 and Africa’s Displacement Crisis,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 25, 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Coronavirus Spreads through Africa,” Infographic, March 19, 2020 (updated daily).

- Shannon Smith, “What the Coronavirus Means for Africa,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 4, 2020.

- Stephen Commins, “From Urban Fragility to Urban Stability,” Africa Security Brief No. 35, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 12, 2018.

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

- Cédric Moro, CoViD19 Africa.

More on: COVID-19 Health & Security