Women protest in Bamenda, Cameroon, in response to a Sept. 3, 2018, attack on the local Presbyterian School of Science and Technology. (Photo: VOA/Moki Edwin Kindzeka)

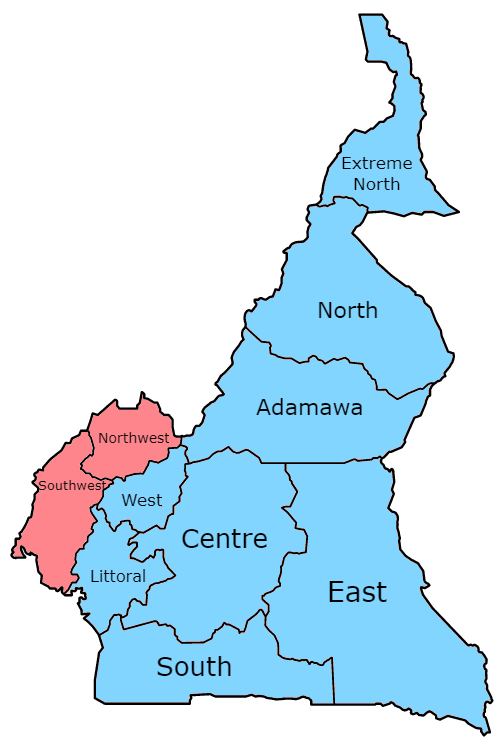

Cameroon faces a poignant irony. It has just held a presidential election, yet the process has been largely overshadowed both by the lack of suspense in its outcome and the growing unrest gripping the country’s Anglophone Northwest and Southwest provinces.

Since 2016, these two provinces, representing roughly 20 percent of Cameroon’s 25 million citizens, have been shaken by a campaign against the discriminatory treatment of Anglophones. The protests began in October 2016 when peaceful demonstrations were organized by lawyers and teachers unions who demanded the right to teach in English, have access to Cameroonian legal texts in English, and interact with English-speaking state representatives. In the process, some participants chanted independence slogans, and the Cameroonian flag was burned.

The two official languages of Cameroon: French (blue) and English (red). (Image: Golbez)

Feeling threatened, the Cameroonian government responded repressively to this movement, repelling demonstrators with tear gas and live ammunition. More than 80 journalists, lawyers, and ordinary protesters have been detained. And the government suspended the Internet in the two Anglophone provinces from January to April 2017, fueling more protests and raising concern within the international community.

The government also labeled all protesters as radical separatists and mobilized elements of the Rapid Intervention Battalion (BIR), the elite unit of the Cameroonian army known for its aggressive methods. Cameroonian soldiers have responded to attacks from separatists with brutal retaliation, burning down entire villages and indiscriminately killing, arresting, and torturing dozens of people within the Anglophone regions, as well as in Nigeria. On October 1, 2018, the anniversary of Cameroon’s unification as a single state, the government imposed a number of restrictive measures aimed at preventing further demonstrations in the Anglophone provinces: suspending public transportation, closing businesses and public places, and banning gatherings of over four people, among other measures.

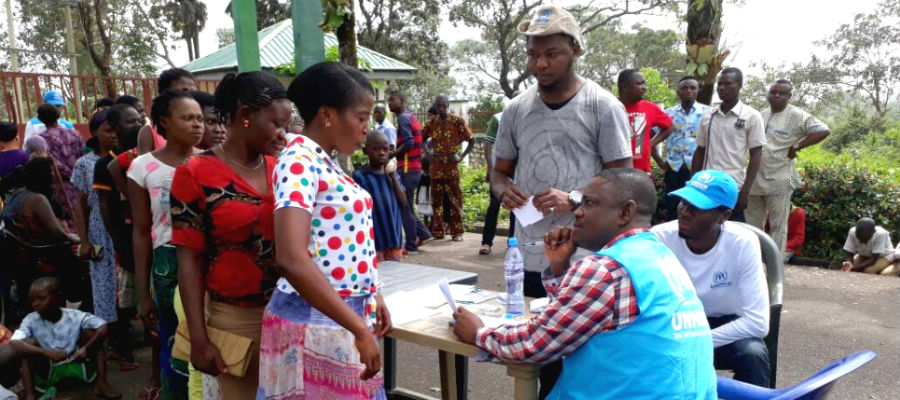

At least 420 civilians have already lost their lives in the ensuing conflict, while nearly 200,000 people have fled their homes to the bush or Francophone areas. Another 40,000 have found refuge in Nigeria. The exodus has accelerated with the increase of violence. The instability has also affected food security in the Anglophone areas, with nearly a half million people facing a food crisis.

In response, some elements of the protest movement have radicalized, turning to armed struggle and calling for secession. Further expanding their movement, they have called on residents in Anglophone areas to avoid urban centers on designated “ville morte” days, threatening violence against any who disobeyed. Several dozen schools, buildings, and administrative vehicles were burned. On October 1, 2017, leaders of the protest proclaimed the independence of the “Republic of Ambazonia” for the Northwest and Southwest provinces, marking a point of no return in the nascent conflict. While traditionally marked with festivities throughout the country, the 46th National Day of Cameroon, May 20, 2018, was boycotted in the English-speaking provinces.

The government labeled all protesters as radical separatists.

Armed groups claiming to be part of the new Anglophone state have emerged, such as the Ambazonian Defense Forces, the Southern Cameroon Defense Forces, the Ambazonia Restoration Army, and several other smaller groups. Altogether the armed separatists are estimated to comprise a few hundred combatants. Since the summer of 2017, at least 170 members of the security forces have been killed, and numerous Cameroonian state officials have been abducted. In September 2018, a group of armed men attacked a school near Buea in the southwest, injuring more than 20 people, including children. Threats by separatists to prevent voting in the presidential election in the Anglophones provinces further suppressed turnout to an estimated 5 percent of eligible voters. The armed separatists have also threatened to attack the country’s most populated urban areas, such as Douala and Yaoundé, in the Francophone regions.

In a report released in July 2018, Human Rights Watch accused both Cameroonian security forces and separatist fighters of serious human rights violations on civilians in both provinces. Despite repeated requests, the United Nations has not been allowed to visit the area. In July 2018, former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Raad Al-Hussein expressed concern, citing reports of “kidnappings, targeted killings of police and local authorities, the destruction of schools by armed elements,” and “killings, excessive use of force, burning down of houses, arbitrary detentions and torture” by government forces. But the government has not yet acted upon his appeal to launch independent investigations into human rights violations.

In an attempt to maintain the illusion of normality, Cameroonian authorities have tried to stem the outflow of residents from the English-speaking provinces by demanding a “reason” why citizens are trying to flee into the French-speaking regions. However, the displacement speaks for itself. Violence in the Anglophone provinces continues to escalate with an ever-increasing number of civilian victims. Today, the country faces a serious risk of conflagration.

A Crisis That Has Been Building for Some Time

Cameroon is an example of a conflict that could have been avoided.

Cameroon is an example of a conflict that could have been avoided. As Dr. Christopher Fomunyoh has observed, this is an entirely “man-made crisis.” English-speaking Cameroonians have long expressed their frustrations toward the discrimination their community faces and the perception of institutional marginalization. It is the failure to take these concerns seriously that has brought the country to the current juncture.

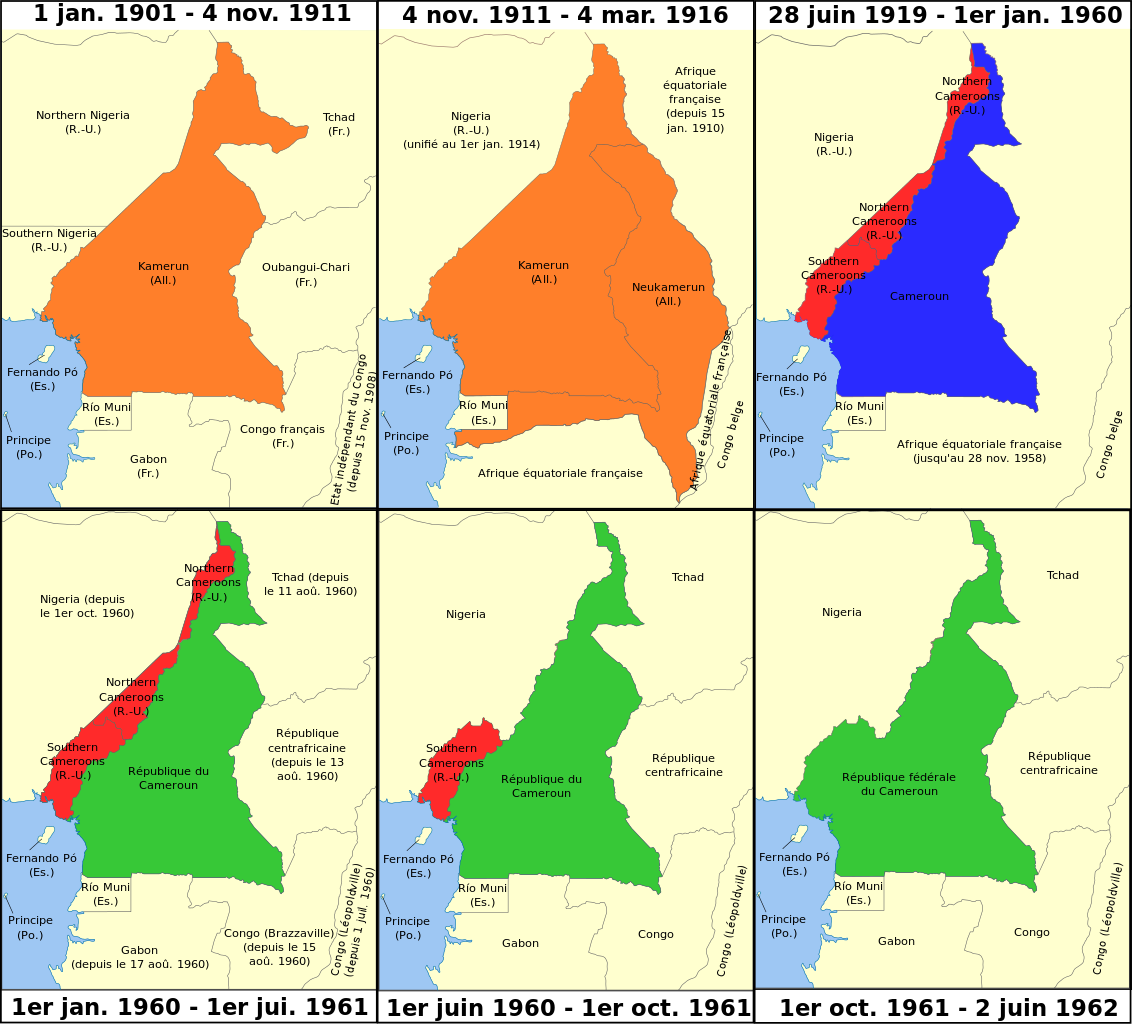

The roots of the crisis also trace back to the country’s origins. The territory that is now Cameroon became a German colony in 1884. Following World War I, Germany lost all of its overseas colonies, leaving most of the territory to be administrated by the French and the western provinces overseen by the United Kingdom. In 1960, a year before Cameroon gained its independence, the two Anglophone provinces voted to join their French-speaking counterparts in what became “the federal Republic of Cameroon.” This federal arrangement was intended to establish a framework where Anglophones and Francophones had the same rights and where their differences would be respected and represented within Cameroonian institutions.

But things soon took a different turn. In May 1972, a referendum was held that led to the approval of the new name of the “United Republic of Cameroon.” Subsequent constitutional reforms started to blur the bilingual and bicultural features of the country. This trend continued with Paul Biya’s accession to the presidency in 1982. He systematically pursued measures that promoted the centralization of the country. The following year, the English-speaking region was divided into two provinces, Northwest and Southwest. In 1984, Biya abandoned the term “united,” the country became the “Republic of Cameroon,” and the second star on the flag, representing the English-speaking region, was removed.

The evolution of Cameroon’s borders from 1901 to 1972. (Image: August 89)

Over the years, centralization has been progressively reinforced, along with the inexorable shrinking of democratic space and individual freedoms. Despite the emergence of Anglophone political movements, the predominance of French and Francophone cultural references became widespread, contributing to the growing sense among Anglophones of a steady loss of culture and a dilution of their identity. They have repeatedly tried to protest against this drift, but the government has generally been resistant to their claims. For many years, Anglophones held out hope for change—until it became clear that the Biya government had no intention of altering the status quo. In 2017, out of 36 ministers, only one was Anglophone. In 2018, the president of the Senate, the president of the National Assembly, the first president of the Supreme Court, and the president of the Constitutional Council were all French-speaking. This has fueled a growing resentment among the youth in the English-speaking regions, who have become increasingly sensitized to the issue and found global resonance for their grievances through social media. It is the combination of this lack of representation along with the exasperation of the Anglophone youth in the face of government indifference that eventually provoked the protests of 2016.

Fear that Autonomy for Anglophones May Lead to Demands for Democracy Nationally

Even though Biya has said repeatedly that he is “ready for dialogue,” the government has failed to offer a sincere and concrete path out of the crisis. Calling the separatists “terrorists” and violently repressing peaceful demonstrations has contributed to the escalation and strengthened the hand of the most radical separatist actors. Moreover, with the support of a highly engaged and resourced Cameroonian diaspora, armed separatists have firmly established themselves. Despite the many casualties within the separatists’ ranks, the harsh and indiscriminate tactics of the Cameroonian security forces have strengthened the fighters’ determination.

Cameroonian authorities, meanwhile, have sought to enforce the status quo at all costs. This strategy is based on the fear that giving more autonomy to Anglophones would in turn galvanize demands for greater democratic openness and respect for human rights among the general population. But this calculation has led to a political and military impasse, placing the future of Cameroon as a unitary nation under threat. The country now faces the risk of a prolonged civil war whose consequences may go far beyond what Cameroonian officials have imagined.

The Rise of the Hardliners

President of Cameroun Paul Biya. (Photo: Amanda Lucidon)

It is becoming increasingly clear that Biya is no longer the only captain steering the Cameroonian ship of state. Aged 85, he travels abroad so frequently that he has been nicknamed “the absent president” by some critics. His prolonged absences and his faltering health have resulted in the transfer of the management of most important portfolios to senior aides. These ministers and members of the administration, all French-speaking, have adopted particularly uncompromising positions in the face of the separatist challenge. Accordingly, Foumane Akame, head of the judiciary in Cameroon for almost 20 years and legal adviser to the head of state; Laurent Esso, Minister of Justice and friend of the president; Edgard Alain Mebe Ngo’o, Minister of Transportation and former Director of Cabinet; and the Minister of Defense, Joseph Beti Assomo, have played increasingly leading roles in Cameroonian politics.

Toward a Resolution to the Conflict

Ordinarily, neighboring countries could be expected to be actively involved in finding a mediated solution to such a political crisis. However, in the case of Cameroon, regional bodies and neighboring countries have remained remarkably discreet. Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) leaders have largely refrained from commenting on the situation, in part, due to other crises in the region. Nigeria shares a common border with the English-speaking provinces and is therefore the neighboring country most directly affected by the crisis. However, Nigerian officials apparently want to avoid any suggestion that they are aiding the Cameroonian separatists. Indeed, to prove its good faith, Abuja not only arrested Sisiku Ayuk Tabe, an English-speaking separatist leader, and 46 of his executives in January 2018, but also extradited them to Yaoundé. Nigeria has also allowed Cameroonian troops to conduct operations on Nigerian territory in order to repel the separatists.

Cameroonian refugees in Nigeria. (Photo: UNHCR/Hanson Ghandi Tamfu)

The need for an inclusive dialogue, initiated by a neutral third party, remains crucial, however. From this perspective, the silence of African regional organizations is problematic. ECCAS, the African Union, and the United Nations Office for Central Africa (UNOCA) all have key roles to play. ECCAS could propose a high-level mediator—for example, a former African head of state or an African personality known for a commitment to peace—who would be seen as an honest broker by both parties and capable of negotiating a cessation of hostilities. At the same time, civilian access to humanitarian aid and safe areas should be guaranteed.

Ultimately, it is up to the Cameroonian actors to work out a resolution to this conflict. Events have clearly shown that the recourse to violence by both sides has only empowered the hardliners in each camp and made the process of finding solutions more difficult. In this regard, the strategy adopted by some of the separatists toward their fellow citizens—forcing families to stop sending their children to school and threatening reprisals against those who vote—is as damaging to peace and restoring trust among citizens as the government’s heavy-handed tactics.

Governance deficiencies have also fueled the resentment of the larger Cameroonian population, beyond the English-speaking regions.

In the end, it will be necessary for all conflict stakeholders to sit down at the negotiating table to address the grievances of Anglophones in the broadest possible way. This dialogue should include the major political actors but also representatives of civil society. As important as any particular prescription will be that mediators take the necessary steps to demonstrate to Anglophones that their grievances are understood and that there is a commitment to ending the discrimination they face. This dialogue could ultimately redefine the principles of a unitary and peaceful Cameroon, where the rights of all citizens are effectively respected and taken into account.

Beyond the question of the treatment of Anglophones, the nature of the regime must be examined. Inequitable access to government services, widespread corruption, and discrimination have created a fertile ground for the emergence and violent radicalization of those with grievances. These governance deficiencies have also fueled the resentment of the larger Cameroonian population, beyond the English-speaking regions. This majority is demanding a profound change in the way the country is run. Despite Biya’s impressive longevity, the country will sooner or later have to choose a new leader. In order to deal with this scenario when it arrives, it would be useful to launch a sincere and in-depth examination of the reforms needed to move the country forward. While those around Biya may believe they can continue the same governance style after him, they underestimate the depth of the desire for change in the country, especially among youth. Rather, Cameroonian leaders will best protect their interests by initiating an ambitious reform process proactively. Time is of the essence. Experience elsewhere in Africa shows that once the dynamics of a conflict take hold, politics becomes increasingly difficult, and the consequences heavier and longer lasting.

Africa Center Experts

- Pauline Le Roux, Visiting Assistant Research Fellow

- Alix Boucher, Assistant Research Fellow

Additional Resources

- Human Rights Watch, “Cameroon: Killings, Destruction in Anglophone Regions,” report, July 19, 2018.

- Christopher Fomunyoh, “Understanding Cameroon’s Crisis of Governance,” Video, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, December 11, 2017.

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Research Paper No. 6, July 31, 2014.

More on: Democratization Cameroon